Chapter 5

Lawyers

Lawyers are an essential—if unloved—feature of every developed legal system. They are vilified, mocked, and disparaged. The humour of a multitude of lawyer jokes springs from their assault on lawyers’ venality, dishonesty, and insensitivity. One jibe asks: ‘How can you tell when a lawyer is lying?’ The answer: ‘His lips are moving’. Another sardonically laments: ‘Isn’t it a shame how 99 per cent of lawyers give the whole profession a bad name?’ And Mark Twain is reputed to have quipped: ‘It is interesting to note that criminals have multiplied of late, and lawyers have also; but I repeat myself.’

It seems futile to attempt to explain this antipathy which rests on a combination of legitimate discontent with and misunderstanding of the legal profession. It is certainly true that, along with bankers, politicians, and estate agents, lawyers attract little affection. An independent bar is, however, a vital component of the rule of law; without accessible lawyers to provide citizens with competent representation, the ideals of the legal system ring hollow. And this is acknowledged in most jurisdictions by the provision of legal aid in criminal cases. So, for example, legal aid is a right recognized by Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights. It requires that defendants be provided with counsel and, if they are unable to afford their own lawyer, one is made available without charge.

9. Lawyer Atticus Finch, played by Gregory Peck in the film of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Hollywood’s heroic depiction of the lawyer, replicated in endless television series, robustly and eloquently pursuing the cause of justice for their client, is a far cry from the reality of real lawyers’ lives (see Figure 9). Advocacy in court represents a small, though important, part of the profession’s work. Most lawyers, however, are preoccupied daily with drafting (contracts, trusts, wills, and other documents), advising clients, conducting negotiations, conveying property, and other rather less glamorous tasks. Yet even if the majority of lawyers never set foot in a court, the essence of lawyering is the battle waged on behalf of the client. In this campaign the skills of advocacy, whether in oral or written form, are paramount. Law is often war, and the lawyer is the warrior (see Box 13).

Box 13 Waltzing lawyers

The lawyers have twisted it into such a state of bedevilment that the original merits of the case have long disappeared from the face of the earth. It’s about a Will, and the trusts under a Will—or it was, once. It’s about nothing but Costs, now. We are always appearing, and disappearing, and swearing, and interrogating, and filing, and cross-filing, and arguing, and sealing, and motioning, and referring, and reporting, and revolving about the Lord Chancellor and all his satellites, and equitably waltzing ourselves off to dusty death, about Costs. That’s the great question. All the rest, by some extraordinary means, has melted away.

Charles Dickens, Bleak House

Common lawyers

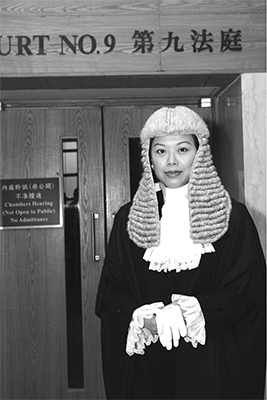

To many, the English legal profession, adaptations of which exist in common law jurisdictions of the former British Commonwealth, appears bizarre—grotesquely anachronistic with its wigs, gowns, and stilted forms of address (see Figure 10). Though some of these quaint, archaic features have been eradicated in a few common law countries, they have shown a remarkable tenacity, especially in England. Polls of practitioners and public have proved inconclusive. Wigs on the heads of many barristers and judges seem firmly fixed for some time yet.

The origins of the common law profession are, of course, steeped in English history—and logic is thus not necessarily among its justifications. It is divided between two principal species of lawyer: barristers and solicitors. Barristers (often called ‘counsel’) constitute a small minority of the legal profession (roughly 10 per cent in most jurisdictions) and, rightly or wrongly, are regarded, especially by themselves, as the superior branch of the profession. Recent years have witnessed a number of fairly sweeping changes, many of which have diminished the privileges of barristers (or ‘the bar’). These reforms have largely been animated by political unease regarding the soaring costs of legal services as a result of the restrictive practices of the bar.

10. Hong Kong senior counsel in her ceremonial wig and silk gown.

Barristers have minimal direct contact with their ‘lay clients’. They are ‘briefed’ by solicitors, and it is normally a requirement that during meetings (or ‘conferences’) with clients the solicitor must be present. An exception is, however, made for certain professions, including accountants and surveyors, who may confer with a barrister without the presence of a solicitor. In most cases, however, dealings must be carried out through the solicitor who is responsible for paying the barrister’s fees.

English barristers are ‘called’ to the bar by one of the four Inns of Court, ancient institutions that since the 16th century have governed entry to this branch of the profession. Unlike the overwhelming majority of solicitors, barristers have full rights of audience, allowing them to appear before any court. Generally, solicitors have rights of audience only before the lower courts, though in recent years the position has changed and some solicitors, certified as ‘solicitor advocates’, may represent their clients as advocates in the higher courts. The traditional separation is gradually breaking down.

Nevertheless, two major distinctions between the two categories of lawyer remain. First, barristers are invariably instructed by solicitors, rather than directly by the client, whereas clients go directly to solicitors. Second, unlike solicitors, barristers operate as sole practitioners, and are prohibited from forming partnerships. Instead, barristers generally form sets of chambers in which resources and expenses are shared. But it is now possible for barristers to be employed by firms of solicitors, companies, or other institutions as in-house lawyers.

Other transformations have occurred. For example, barristers are now permitted to advertise their services and their fees—a hitherto unthinkable commercial contamination. Nor are they limited to practising from a set of chambers; after three years’ ‘call’, they may work from home.

The split profession has been attacked from a number of quarters. Why, it is not unreasonably asked, should a client effectively pay for two lawyers when, as in the United States, for instance, one will do? The case for fusion between the two branches—either formal or in effect (as exists in the common law provinces of Canada, most Australian states, New Zealand, Malaysia, and Singapore) has been met by a number of responses. In particular, it is argued by defenders of the status quo that an independent barrister offers a detached, expert evaluation of the client’s case. Also, solicitors, especially those from small firms, who often lack a high degree of specialization, may draw on the expertise of a wide range of barristerial skills. This enables them to compete with larger firms who boast numerous specialists.

The United States draws no distinction: all are attorneys. Anyone who passes the state bar examination may appear in the courts of that state. Some state appeal courts require attorneys to have a certificate of admission to plead and practise in that court. To appear before a federal court, an attorney requires specific admission to that court’s bar.

A fundamental tenet of counsel’s duty in some common law countries (but not, surprisingly, in the United States) is the so-called ‘cab-rank rule’ under which ‘no counsel is entitled to refuse to act in a sphere in which he or she practises, and on being tendered a proper fee, for any person however unpopular or offensive he or his opinions may be’. Like a taxi driver who is generally obliged to accept any passenger, a barrister is bound to accept any brief unless there are circumstances to justify a refusal, such as that the area of law lies outside of his expertise or experience, or where his professional commitments prevent him from devoting sufficient time to the case.

In the absence of such a rule, advocates would be reluctant to appear on behalf of abhorrent, immoral, or malevolent clients charged, for example, with heinous crimes such as child molestation. Nevertheless, in practice it is not difficult for a barrister to find a reason why the brief should not be accepted. Apart from the case involving an area of law beyond his or her capability, the human element is always present: time is more easily found for a lucrative brief than one which concerns an intractable or hopeless case. But it represents a sound statement of professional duty, emphasizing the role of lawyer as ‘hired gun’ who acts fearlessly for any client regardless of the merits of their case.

A striking feature of the training of common lawyers has been the role of some form of apprenticeship (see later in the chapter). Indeed, it was only towards the end of the 19th century that English universities taught any law at all. And large-scale university legal education in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand had to await the 20th century, though some universities had established law schools earlier (notably Harvard in 1817).

Civil lawyers

Lawyers in the civil law world differ fundamentally from their common law colleagues. Indeed, the very concept of a legal profession in the major civil law jurisdictions of Europe, Latin America, Japan, and Scandinavia is problematic. In the words of a leading authority on the subject, ‘The common law folk concept of “lawyer” has no counterpart in European languages.’ Civil law jurisdictions recognize two categories of legal professionals: the jurist and the private practitioner. The former comprises law graduates, while the latter, unlike the position in common law countries, does not represent the nucleus of the legal profession. Instead, ‘other subsets of law graduates take precedence—historically, numerically, and ideologically. These include the magistracy (judges and prosecutors) … civil servants, law professors, and lawyers employed in commerce and industry.’

Students in civil law countries typically decide on their future after graduation. And, as mobility within the profession is limited, in many jurisdictions this choice is likely to be conclusive. They may choose to pursue the career of a judge, a public prosecutor, a government lawyer, an advocate, or notary. Private practice is therefore generally divided between advocates and notaries. The former has direct contact with clients and represents them in court. After graduating from law school, advocates normally serve an apprenticeship with experienced lawyers for a number of years, and then tend to practise as sole practitioners or in small firms.

To become a notary usually requires passing a state examination. Notaries draft legal documents such as wills and contracts, authenticate such documents in legal proceedings, and maintain records on, or provide copies of, authenticated documents. Government lawyers serve either as public prosecutors or as lawyers for government agencies. The public prosecutor performs a twin function. In criminal cases, he or she prepares the government’s case; while in certain civil cases they represent the public interest.

In most civil law jurisdictions, the state plays a considerably more important role in the training, entry, and employment of lawyers than is the case in the common law world. Unlike the traditional position in common law countries where lawyers qualify by serving an apprenticeship, the state controls the number of jurists it will employ, and the universities mediate entry into private practice.

There are important differences between the two systems in respect of the organization of legal education. Broadly speaking, in most common law jurisdictions (with the conspicuous exception of England and Hong Kong), law is a postgraduate degree or, as in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, it may be combined with an undergraduate degree in another discipline. In the civil law world, on the other hand, law is an undergraduate course. While the common law curriculum is strongly influenced by the legal profession, the state in civil law jurisdictions exercises a dominant function in this respect. The legal profession in most common law countries administers entry examinations, whereas, given the role of universities as gatekeepers in civil law countries, further examinations are generally redundant, and a law degree suffices.

The function of gatekeeping in common law countries tends to be discharged by apprenticeship with a private practitioner. So, for example, aspiring barristers must pass the bar examinations. In order to practise at the bar, they are required to serve two six-month pupillages in chambers, attending conferences with solicitors conducted by their ‘pupil master’ (a more senior barrister), and sitting in court, assisting in preparing cases, drafting opinions, and so on. Pupillage is usually unpaid, although they are now increasingly funded so as to guarantee the pupil’s earnings up to a fixed level. During the second six months of pupillage, the barrister may engage in limited practice and be instructed in his or her own right. With the exception of barristers, lawyers in private practice operate as members of a firm whose size may vary from a single lawyer to mega-firms of hundreds of lawyers.

Regulation of the profession

Bar associations, bar councils, and law societies are among the numerous organizations that supervise the admission, licensing, education, and regulation of common lawyers. The civil law prefers the term ‘advocates’ (which more accurately describes their principal function, and their counterpart organizations are dubbed chambers, orders, faculties, or colleges of advocates). Although their designations differ, they generally share a concern to limit the number of lawyers in practice, and defend their monopoly.

In certain jurisdictions (particularly small ones like Belgium and New Zealand), lawyers are admitted and regulated at the national level. Federal states (such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and Germany) inevitably exercise provincial or state regulation. Italian lawyers are admitted at the regional level.

While regulation in some countries is undertaken by the judiciary and, under its aegis, an independent legal profession, lawyers in other jurisdictions, especially in the civil law world, are subject to government control in the shape of the ministry of justice.

Legal aid

The right of access to justice rings hollow without the provision of free legal advice and assistance to the poor, especially in criminal cases. Many societies therefore grant legal aid to persons incapable of paying for a lawyer. Even in respect of civil litigation, however, elementary norms of fairness would be undermined where an impecunious defendant is sued by an affluent plaintiff or the state. Any semblance of equality before the law is thereby shattered. The cost involved (to both the state and the individual seeking legal aid) generally results in preference being given to assisting those charged with criminal offences, though some jurisdictions do supply free legal aid in civil cases. Certain systems of legal aid provide lawyers who are employed exclusively to act for eligible, impoverished clients. Others appoint private practitioners to represent such individuals.

The United States Supreme Court in the landmark case of Gideon v Wainwright in 1963 unanimously ruled that states are constitutionally obliged to provide counsel in criminal cases to represent defendants who are unable to afford them. These so-called ‘public defenders’ may be appointed by the court to assist and represent indigent individuals, but their efficacy is often compromised by their youth, inexperience, and excessive workload.

Unrepresented defendants in criminal trials are at a considerable disadvantage. Without legal aid, the poor are denied their right to equality before the law and to a fair trial. As the Supreme Court declared in Gideon:

[R]eason and reflection require us to recognize that in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him. This seems to us to be an obvious truth … This noble ideal cannot be realized if the poor man charged with crime has to face his accusers without a lawyer to assist him.

Sadly, this ‘noble ideal’ remains in many countries just that.