Chapter 6

The future of the law

Law, like war, seems to be an inescapable fact of the human condition. But what is its future? The law is, of course, in a constant state of flux. This is nicely expressed by the illustrious American Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo:

Existing rules and principles can give us our present location, our bearings, our latitude and longitude. The inn that shelters us for the night is not the journey’s end. The law, like the traveller, must be ready for the morrow. It must have a principle of growth.

In our rapidly changing world, growth and adaptation are more pressing than ever if the law is to respond adequately to the novel challenges—and threats—that it faces. The character of law has unquestionably undergone profound transformations in the last fifty years, yet its future is uncertain. Some argue that the law is in its death throes, while others advance a different prognosis that discerns numerous signs of law’s enduring strength. Which is it? Curiously, there is some truth in both standpoints.

Those who suggest that law is moribund point to signs of the infirmity of many advanced legal systems. Symptoms of this demise include the privatization of law: the settlement of cases out of court, plea-bargaining, ADR, the spectacular rise of regulatory agencies with wide discretionary powers, and the decline of the rule of law in several countries.

On the other hand, the resilience of law is evident in the extension of the law’s tentacles into the private domain in pursuit of efficiency, social justice, and other political goals; the globalization of law and its internationalization through the United Nations, regional organizations, and the European Union; and the massive impact of technology on the law.

This concluding chapter attempts to uncover some of the major shifts in contemporary society and the formidable challenges they pose to the law.

Law and change

Various attempts have been made to chart the course of legal development. Legal historians have sought to identify the central features in the evolution of law, and, hence, to place different societies along this continuum. In the late 19th century, the eminent scholar Sir Henry Maine famously contended that law and society had previously progressed ‘from status to contract’. In other words, in the ancient world individuals were closely bound by status to traditional groups, whereas in modern societies individuals are regarded as autonomous beings—they are free to enter into contracts and form associations with whomever they choose.

But this transition may have reversed. In many instances freedom of contract is more apparent than real. For example, what choice does the consumer have when faced with a standard-form contract (or contract of adhesion) for telecommunications, electricity, or other utilities? And where is the employee who, when offered a job and presented with a standard-form contract by his multinational employee, would attempt to renegotiate the terms? It is true that many advanced legal systems seek to improve the bargaining position of the individual through various forms of consumer protection legislation. Yet when a lightweight steps into the ring with a heavyweight, the outcome is rarely in doubt. Has ‘status’ returned in the form of ‘consumer’ or ‘employee’?

The ideas of the German social theorist, Max Weber, have exerted a powerful influence on thinking about law and its development. He advanced a ‘typology’ of law based on the different categories of legal thought. At its heart is the idea of ‘rationality’. He distinguishes between ‘formal’ systems and ‘substantive’ systems. The core of this division is the extent to which a system is ‘internally self-sufficient’, i.e. the rules and procedures required for decision making are available within the system. Second, he separates ‘rational’ from ‘irrational’ systems. ‘Rationality’ refers to the manner in which legal rules and procedures are applied. The highest stage of rationality is reached when all legal propositions constitute a logically clear, internally consistent system of rules under which every conceivable fact or situation is included.

Weber gives as an example of a formally legal irrational system the phenomenon of trial by ordeal where guilt is determined by an appeal to some supernatural force. An illustration of substantive legal irrationality is where a judge decides a case on the basis of his personal opinion without any reference to rules. A decision of a judge is substantively rational, according to Weber, when he refers not to rules but moral principles or concepts of justice. Finally, where a judge defers to a body of doctrine consisting of legal rules and principles, the system constitutes one of formal logical legal rationality. It is towards this ideal type that Weber’s theory of legal evolution progresses.

In many societies, however, Weber’s model of a rational, comprehensive, and coherent legal system is undermined by the rapid rise in administrative control. Contemporary societies manifest an enormous expansion in the jurisdiction of administrative agencies. These bodies, normally creatures of statute, are vested with extensive discretionary powers. In some cases, their decisions are explicitly exempted from judicial oversight.

In several European countries, for example, the privatization of formerly nationalized industries (such as utilities and telecommunications) has spawned a host of regulatory agencies with powers to investigate, create rules, and impose penalties. The ordinary courts may be marginalized, and hence the role of law itself becomes distorted. This development poses a threat to the authority and openness of the court system described in Chapter 4. Moreover, the enlargement of discretionary powers undermines the rule of law’s insistence on the observance of clear rules that specify individual rights and duties.

Disappearing law?

Among the more radical theories of legal development is the Marxist idea that law is doomed to disappear completely. This prediction is grounded in the idea of historicism: social evolution is explained as a movement driven by inexorable historical forces. Marx and Engels propounded the theory of ‘dialectical materialism’, which explains the unfolding of history as the development of a thesis, its opposite (or antithesis), and, out of the ensuing conflict, its resolution in a synthesis.

Marx argued that each period of economic development has a corresponding class system. During the period of hand-mill production, for instance, the feudal system of classes existed. When steam-mill production developed, capitalism replaced feudalism. Classes are determined by the means of production, and therefore an individual’s class is dependent on his relation to the means of production. Marx’s ‘historical materialism’ is based on the fact that the means of production are materially determined; it is dialectical, in part, because he sees an inevitable conflict between those two hostile classes. A revolution would eventually occur because the bourgeois mode of production based on individual ownership and unplanned competition, stands in opposition to the increasingly non-individualistic, social character of labour production in the factory.

The proletariat would, he predicted, seize the means of production and establish a ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ which would, in time, be replaced by a classless, communist society in which law would eventually ‘wither away’. Since the law is a vehicle of class oppression, it is superfluous in a classless society. This is the essence of the argument first implied by Marx in his early writings and restated by Lenin. In its more sophisticated version the thesis claims that, following the proletarian revolution, the bourgeois state would be swept aside and replaced by the dictatorship of the proletariat. Society, after reactionary resistance has been defeated, would have no further need for law or state: they would vanish.

But this cheerful prognosis is based on a rather crude equation of law with the coercive suppression of the proletariat. It disregards the fact not only that a considerable body of law serves other functions, but that even, or especially, a communist society requires laws to plan and regulate the economy. To claim that these measures are not ‘law’ is to invite disbelief.

Whatever theory is adopted to explain the manner and form of legal change, it is impossible to deny that the future of law is beset with a host of thorny challenges. Where might the greatest difficulties lie?

Internal challenges

In addition to the problem of bureaucratic regulation and the often unbridled discretion it generates (discussed earlier), there are a number of intractable questions that need to be confronted by legal systems. Some of these were touched on in Chapters 2 and 3. Among the most conspicuous is the increasing threat of terrorism by extremist groups in several countries. It requires little perception to realize that many legal systems are faced with a variety of problems that test the values that lie at their heart. How can a free society reconcile a commitment to liberty with the necessity to confront threats to undermine that very foundation? Absolute security is clearly unattainable, but even moderate protection against terror comes at a price. No airline passenger can be unaware of the cost in respect of the delays and inconvenience that today’s security checks inevitably entail.

Nevertheless, although terrorism and crime in general can never be entirely prevented, modern technology does offer extraordinarily successful tools to deter and apprehend offenders. At the most commonplace level, closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras can monitor unlawful activities, such recordings supplying prosecutors with powerful evidence in court against the videoed villain. To what extent should the law tolerate this kind of surveillance?

Surely, most delinquents would be thwarted were a CCTV camera to record his (or, less likely, her) every move? Law-abiding citizens must feel safer in the knowledge that this surveillance is taking place. Indeed, opinion polls confirm their wide support. Who but the robber, abductor, or bomber has anything to fear from the monitoring of his or her activities in public places? Advances in technology render the tracking of an individual’s financial transactions and email communications simple. The introduction of ‘smart’ ID cards, the use of biometrics, and electronic road pricing are now routine. Only the malevolent could legitimately object to these effective methods of crime control. Would that this comforting view were true.

We cannot afford to pussyfoot with terrorists, but how far should we be willing to trade our freedom for security? In the immediate aftermath of the events of 11 September 2001, politicians, especially in the United States, have understandably sought to enhance the powers of the state to detain suspects for interrogation, intercept communications, and monitor the activities of those who might be engaged in terrorism.

The recent revelations by former US government contractor and whistle-blower, Edward Snowden, exposed the considerable extent of the surveillance conducted by the US National Security Agency (NSA). They included disclosures of spying by both the US and Britain on foreign leaders, and the storage by the NSA of domestic communications containing foreign intelligence information; the suggestion of a crime; threats of serious harm to life or property; or any other evidence that could advance its electronic surveillance—including encrypted communications. Moreover, it emerged that, since December 2012, the NSA has had the capacity to collect a trillion metadata records. Other leaks suggested that the US had spied on the European Union (EU) offices in New York, Washington, DC, and Brussels, as well as the embassies of France, Greece, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, South Korea, and Turkey.

Evidence also appeared to show the existence of an NSA project to collect information from the fibre optic cables that carry most Internet and phone traffic. And it discloses the existence of a programme comprising a network of 500 servers scattered across the world that collect almost all online activities conducted by a user, storing the information in databases searchable by name, email, IP address, region, and language. It also divulged that the private sector, including several telecom companies, provide the British security agency, GCHQ, with unrestricted access to their fibre optic cable networks, carrying a vast quantity of Internet and telephone traffic.

In addition, according to the leaks, the NSA has cracked the encryption methods widely used by millions of individuals and organizations to protect their email, e-commerce, and financial transactions. It is also alleged that the NSA employs its colossal databases to store metadata, such as email correspondence, online searches, and the browsing history of millions of Internet users for up to a year, regardless of whether they are targets of the agency.

The threat of terrorism cannot be taken lightly, but unless individual privacy is to be wholly extinguished, the effective oversight of security services is crucial. In March 2014, President Obama announced that the NSA’s bulk collection of Americans’ telephone records would be terminated. In June 2015 the powers of the NSA to collect telephone data were curbed.

The law faces formidable difficulties in this respect. Draconian powers are probably unavoidable during times of war: arbitrary powers of arrest and detention, imprisonment without trial, secret trials, and the like. How long can a free society tolerate these infringements of liberty? What lasting damage may be inflicted on the rule of law and individual rights? Can the law continue to protect citizens or will citizens need protection from the law? Are the courts able to act as a bulwark against these attacks on freedom?

In Chapter 3, the question of the use of torture was discussed. Can it be justified in order to prevent acts of terror? Methods used by the CIA, we saw, were described in a recent contentious senate report as brutal and ineffective, and a blemish on American values. Several reports of the torture of detainees at the US Guantanamo Bay camp have emerged over the years. The treatment of these individuals (most of whom were captured in Afghanistan) has been strongly condemned as inhumane, in breach of international law, and a denial of the detainees’ legal rights including habeas corpus and access to legal counsel.

There can be little doubt that the law will be placed under growing pressure as it strives to reconcile freedom with the perils of terrorism and extremism that threaten to destroy the values cherished by democratic legal systems (see Box 14).

A less egregious engine of change is the internationalization or globalization of law. The world has witnessed an escalation in the influence and importance of international (the United Nations) or regional organizations (such as the EU). These sources of law diminish the authority of domestic law and legal institutions. Nor has the law been spared the McDonald’s effect of powerful multinational corporations influencing the character of banking, investments, consumer markets, and so on. All have a direct impact on the law.

Box 14 Terrorism and freedom

We need not sacrifice our constitutional freedoms to win the Wars on Terror. Indeed … twenty-first century terrorism poses a danger to those freedoms. Claims that the U.S. Constitution doesn’t apply abroad, or that habeas corpus is a quaint irrelevance, or that persons can be held incommunicado indefinitely, are ones with which I have little sympathy. But neither do I believe that there is a God-given right to not be burdened with carrying an identity card, or to not disclose to the government information we have gladly given to private corporations or that they have collected with our consent.

Philip Bobbitt, Terror and Consent

It is hard to think of a single facet of law that is untouched by globalization (or what is called the internationalization of law). From the development of transnational commerce, markets, and banking to the growing number of problems faced by international law, including, for instance, climate change, international human rights violations, terrorism, and piracy.

Most legal systems face unresolved dilemmas in several of the disciplines discussed in Chapter 2, where I touched upon some of these problems. They are both substantive and procedural, and include several quandaries concerning, to mention only one of countless possible examples, the criminal justice system. What is the future of the criminal trial in the face of complex commercial offences, often involving sophisticated know-how? Is the jury trial appropriate in these circumstances, or at all? Is the civil law inquisitorial system preferable to the common law adversarial approach?

Corruption is a scourge that legal systems need to address. In several jurisdictions, access to the law is patchy. The poor are not always provided with adequate access to the courts and other institutions of dispute resolution. Many legal systems wrestle with the difficult question of compensation for personal injuries, and the effect of insurance on the award of damages. The Internet and other technological developments generate a multiplicity of legal challenges. Some are considered in what follows.

The limits of law

While the law on its own can never transform, or indeed conserve, the social order and its values, it has the capacity to influence and shape attitudes. Efforts to achieve social justice through law have not been an unqualified success. Statutes outlawing racial discrimination, for example, represent only a modest advance in the cause of equality. While little can be accomplished without legal intervention, the limits of law need to be acknowledged. There is a growing tendency to legalize moral and social problems, and even to assume that the values underpinning democratic Western legal systems, and their institutions, can be fruitfully exported or transplanted to less developed countries. This may be a utopian vision. Equally sanguine may be the suggestion that economic development necessarily presages respect for human rights, as is frequently contended in the case of China.

Modern governments espouse highly ambitious legislative programmes that frequently verge upon social engineering. To what extent can legislation genuinely improve society, and combat discrimination and injustice? Or are courts more appropriate vehicles for social change? Where, as in the United States, a vigorous Supreme Court has the clout to declare laws unconstitutional, the legislature has no choice but to fall in line, as it did following the seminal case of Brown v Board of Education of Topeka in 1954. A unanimous court declared the establishment of separate public schools for black and white students ‘inherently unequal’. This landmark decision opened the doors (literally) to integration and the birth of the civil rights movement. Though discrimination will always exist, few would deny that the court’s historic decision changed the law—and society—for the better.

11. Protest against animal cruelty.

Without effective enforcement, laws cannot fulfil their noble aspirations. Legislation prohibiting animal cruelty is a case in point (see Figure 11). Vivisection, battery farming, animal transport, the fur trade, hunting, trapping, circuses, some zoos, and rodeos are merely some of the practices, apart from the direct intentional infliction of pain on an animal, that cause misery and suffering to millions of creatures around the world every day. Anti-cruelty statutes have been enacted in many jurisdictions, yet in the absence of rigorous enforcement these laws constitute mostly empty promises. And enforcement is a major hurdle: detection is largely dependent on inspectors who lack the power of arrest, prosecutors who rarely regard animal cruelty cases as a high priority, and judges who seldom impose adequate punishment, not that the statutory penalty is itself sufficiently stringent (see Boxes 15 and 16).

Box 15 Da Vinci’s code

The time will come when people such as I will look upon the murder of (other) animals as they now look upon the murder of human beings.

Leonardo da Vinci

Box 16 The law and animal suffering

The day may come, when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may come one day to be recognized, that the number of legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum, are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason, or perhaps, the faculty for discourse? … [T]he question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being? … The time will come when humanity will extend its mantle over everything which breathes …

Jeremy Bentham, Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation

In an increasingly anxious world, there is an understandable tendency to look to the law to resolve the manifold threats to our future. In recent years, the dangers of pollution, depletion of the ozone layer, global warming, and other threats to the survival of many species of animal, marine, bird, and plant life have assumed greater importance and urgency. A growing number of nations have introduced legislation to attempt to limit or control the destruction of the planet. The law, however, often proves to be a rather blunt instrument. For example, in the case of the criminal liability of a company for pollution, a conviction depends on proof that those who control the company had the requisite knowledge or intention. This is notoriously difficult to prove. And even where these acts are strict liability offences, the fines imposed by courts have a limited deterrent effect. It may be that the numerous international treaties, conventions, and declarations on almost every aspect of environmental protection are likely to be more effective, though, as with the law the predictable stumbling block is effective implementation.

Law and injustice

The law may, of course, be the source of injustice. As mentioned in Chapter 3, apartheid was a creature of the law. And the same can be said of the atrocities of the Third Reich. And sometimes courts are guilty of injustice. The infamous Dreyfus affair in France is a striking example of the conviction and punishment of an innocent person as a result of a combination of incompetence and anti-Semitism. Though Dreyfus was eventually exonerated, the case demonstrates how even judges may be susceptible to bigotry and prejudice.

The American Supreme Court has not been immune from unjust decisions. In one of its most notorious cases it decided against Dred Scott, a slave who in 1847 applied to a court to obtain his freedom. The judges ruled that no person of African origin could ever become a citizen of the United States, and Scott therefore had no right to bring his case. It also held that the government lacked the power to prohibit slavery.

No less dishonourable was the court’s judgment in Plessy v Ferguson in 1896 which upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation in public facilities under the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine. It took more than half a century for the court to overrule this decision in their celebrated Brown decision mentioned earlier.

In 1991 in Los Angeles the case of Rodney King sparked riots after the acquittal of police officers who had struck him up to fifty-six times with metal batons, kicked him, and shot him with a Taser stun gun. A number of bystanders witnessed the beating, one of whom videotaped the incident. King suffered a fractured skull and nerve damage to his face. Though some of the officers were subsequently convicted by a federal court on charges of violating King’s constitutional rights, and imprisoned, none of the prosecutions specifically alleged racial motivation. The police shooting of black suspects and the failure to prosecute the alleged offenders remains a highly volatile issue in the United States.

We should not be surprised that miscarriages of justice occur. Courts are not infallible, and there is always the possibility of errors, oversights, and contaminated or false evidence that can lead to the conviction of an innocent defendant. One of the strongest arguments against capital punishment is founded on this terrible prospect.

Technological challenges

There is nothing new about the law’s struggle to keep abreast with technology. Yet the last twenty years have witnessed an unprecedented transformation of the contest. Digital disquiet easily spawns alarm and anxiety. Information technology, to select only one obvious instance, poses enormous challenges to the law. Attempts legally to control the Internet, its operation, or content, have been notoriously unsuccessful. Indeed, its very anarchy and resistance to regulation is, in the minds of many, its strength and attraction. But is cyberspace beyond regulation? Professor Lawrence Lessig has cogently argued that it is indeed susceptible to control, not necessarily by law, but through its essential make-up, its ‘code’: software and hardware that constitute cyberspace. That code, he suggests, can either produce a place where freedom prevails or one of oppressive control.

In fact, commercial considerations increasingly render cyberspace decidedly amenable to regulation; it has become a place in which conduct is more strongly controlled than in real space. In the end, Lessig maintains, it is a matter for us to determine; the choice is one of architecture: what sort of code should govern cyberspace, and who will control it? And in this respect, the central legal issue is code. We need to choose the values and principles which should animate that code.

Information is no longer merely power. It is big business. In recent years, the fastest growing component of international trade is the service sector. It accounts for more than one-third of world trade—and continues to expand. It is common to identify, as a central feature of modern industrialized societies, their dependence on the storage of information. The use of computers facilitates, of course, considerably greater efficiency and velocity in the collection, storage, retrieval, and transfer of information. The everyday functions of the state as well as private bodies require a continual supply of data about individuals in order to administer effectively the numerous services that are integral to contemporary life and the expectations of citizens. Thus, to mention only the most conspicuous examples, the provision of health care, social security, and the prevention and detection of crime by law enforcement authorities assume the accessibility of a vast quantity of such data, and, hence, a willingness of the public to furnish them. Equally in the private sector, the provision of credit, insurance, and employment generate an almost insatiable hunger for information.

Big brother?

Can the law control the seemingly relentless slide towards an Orwellian nightmare? ‘Low-tech’ collection of transactional data in both the public and private sector has become commonplace. In addition to the routine surveillance by CCTV in public places, the monitoring of mobile telephones, the workplace, vehicles, electronic communications, and online activity are increasingly taken for granted in most advanced societies. The privacy prognosis is not encouraging; the future promises more sophisticated and alarming intrusions into our private lives, including the greater use of biometrics, and sense-enhanced searches such as satellite monitoring, and penetrating walls and clothing.

As cyberspace becomes an increasingly perilous domain, we learn daily of new, alarming assaults on its citizens. This slide towards pervasive surveillance coincides with the mounting fears, expressed well before 9/11, about the disturbing capacity of the new technology to undermine our liberty. Reports of the fragility of privacy have, of course, been sounded for at least a century. But in the last decade they have assumed a more urgent form.

And here lies a paradox. On the one hand, recent advances in the power of computers have been decried as the nemesis of whatever vestiges of our privacy still survive. On the other, the Internet is acclaimed as a utopia. When clichés contend, it is imprudent to expect sensible resolutions of the problems they embody, but between these two exaggerated claims, something resembling the truth probably resides. In respect of the future of privacy, at least, there can be little doubt that the legal questions are changing before our eyes. And if, in the flat-footed domain of atoms, we have achieved only limited success in protecting individuals against the depredations of surveillance, how much better the prospects in our brave new binary world?

In 2010 the now famous (or infamous) international, online, journalistic NGO (non-governmental organization), WikiLeaks, led by Julian Assange, began releasing a huge number of documents relating mainly to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Towards the end of that year it released almost 400,000 secret United States military logs detailing its operations in Iraq, and it collaborated with several media organizations to disclose US State Department diplomatic cables. In 2013, Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning, a twenty-five-year-old soldier, was convicted of twenty charges in connection with the leaks, including espionage, and sentenced to thirty-five years’ imprisonment.

But the activities of WikiLeaks, though continuing, were eclipsed by the massive revelations in June 2013 by a former US government contractor, Edward Snowden. In a dramatic sequence of whistle-blowing, he revealed the enormous extent of the surveillance conducted by the NSA. It disclosed that the NSA was collecting the telephone records of tens of millions of Americans. This was soon followed by evidence that the NSA had direct access—via the PRISM programme—to the servers of several major tech companies, including Apple, Google, and Microsoft.

The constitutionality of the NSA’s mass collection of telephone phone records recently restricted by a change in the law, as already mentioned, has now been challenged by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The complaint contends that the dragnet under the Patriot Act infringes the right of privacy protected by the Fourth Amendment, as well as the First Amendment rights of free speech and association. The lawsuit seeks to terminate the NSA’s mass domestic surveillance, and to require the deletion of all data collected. A federal judge denied the ACLU’s motion for a preliminary injunction, and granted the government’s motion to dismiss. The ACLU appealed this decision before the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in New York.

When our security is under siege, so—inevitably—is our liberty. A world in which our every movement is observed erodes the very freedom this snooping is often calculated to protect. Naturally, we need to ensure that the social costs of the means employed to enhance security do not outweigh the benefits. Thus, one unsurprising consequence of the installation of CCTV in car parks, shopping malls, airports, and other public places is the displacement of crime; offenders simply go somewhere else. And, apart from the doors this intrusion opens to totalitarianism, a surveillance society can easily generate a climate of mistrust and suspicion, a reduction in the respect for law and those who enforce it, and an intensification of prosecution of offences that are susceptible to easy detection and proof.

European data protection legislation attempts to regulate the collection and use of personal information. But the law is locked in an unceasing struggle to stay ahead of advancing technology. At the heart of the law is the modest proposition that data relating to an identifiable individual should not be collected in the absence of a genuine purpose and the consent of the individual concerned. The new information technology disintegrates national borders; international traffic in personal data is a routine feature of commercial life. The protection afforded to personal data in Country A is, in a digital world, rendered nugatory when it is retrieved on a computer in Country B in which there are no controls over its use. Hence, states with data protection laws frequently proscribe the transfer of data to countries that lack them. Indeed, the EU has in one of its several directives explicitly sought to annihilate these ‘data havens’. Without data protection legislation, countries risk being shut out of the rapidly expanding information business.

At the core of these laws are two central canons of fair information practice that speak for themselves: the ‘use limitation’ and ‘purpose specification’ principles. They require rejuvenation where they already exist, and urgent adoption where they do not (most conspicuously, and indefensibly, in the United States). They may, moreover, be able to provide complementary safeguards for individual privacy in cyberspace.

Developments in biotechnology such as human cloning, embryo stem cell research, genetic engineering, GM crops, and nanotechnology provoke thorny ethical questions and confront traditional legal concepts. Proposals to introduce identity cards and biometrics have attracted strong objections in several jurisdictions. The nature of criminal trials has been transformed by the use of both DNA and CCTV evidence.

Orwellian supervision already appears to be alive and well in several countries. Britain, for example, boasts more than four million CCTV cameras in public places: roughly one for every fourteen inhabitants. It also possesses the world’s largest DNA database, comprising some 5.3 million DNA samples. The temptation to install CCTV cameras by both the public and private sector is not easy to resist. The boundary between the state and business is disintegrating. Information is routinely shared between the two. For example, Google may provide user data when subject to a court order. Or even without it. It is claimed that in the US lucrative provisions exist by which the state outsources data gathering to ten major telecommunications companies, including AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile who reaped considerable sums of money supplying law enforcement authorities with personal telecom information.

More disturbing, however, is the scale of the systematic collection of personal data by major websites such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon. And they frequently comply with government requests for consumers’ personal information. In fact, the capture of such data is fundamental to the business models of the most successful technology firms, and they are increasingly permeating traditional activities such as retail business, health care, finance, entertainment and the media, and insurance. Companies such as PayPal and Visa track online transactions. Google and other agencies obtain private information by cookies and ‘click-throughs’. And so-called private data aggregators collect personal data which they then sell.

These are merely random examples of what has been described as an arms race between privacy-enhancing technology (PETS) and privacy-invading technology (PITS). It is too early to predict which side will triumph.

The future of the right to privacy depends in large part on the ability of the law to formulate an adequately clear definition of the concept itself. This is not only a consequence of the inherent vagueness of the notion of privacy, but also because the ‘right of privacy’ has conspicuously failed to provide adequate support to the private realm when it is intruded upon by competing rights and interests, especially freedom of expression. In our burgeoning information age, the vulnerability of privacy is likely to intensify unless this central democratic value is translated into simple language that is capable of effective regulation.

Other developments have comprehensively altered fundamental features of the legal landscape. The law has been profoundly affected and challenged by numerous other advances in technology. Computer fraud, identity theft, and other cybercrimes, and the pirating of digital music, are examples.

A recent development in the field of data collection and storage is the advent of so-called ‘big data’, used to describe the exponential increase and availability of data. It is characterized by what has been called the ‘three Vs’: volume, velocity, and variety. In respect of the first, the volume is a consequence of the ease of storage of transaction-based data, unstructured data streaming in from social media, and the accumulation of sensor and machine-to-machine data. Second, data are streamed at high velocity from radio frequency identification (RFID) tags, sensors, and smart metering. And third, data assume a multiplicity of forms including structured, numeric data in traditional databases, from line-of-business applications, unstructured text documents, video, audio, email, and financial transactions.

Its advocates claim that it affords opportunities to correlate data in order to combat crime, prevent disease, forecast weather patterns, identify business trends, and so on. Its detractors question the reliability of its correlations, and the interpretation of the results.

New wrongs and rights

Advances in technology are predictably accompanied by new forms of mischief. The law is not always the most effective or appropriate instrument to deploy against these novel depredations. Technology itself frequently offers superior solutions. In the case of the Internet, for example, a variety of measures exist to protect personal data online. These include the encryption, economization, and erasure of personal data.

While new-fangled wrongs will continue to emerge, some transgressions are simply digital versions of old ones. Among the more obvious novel threats, there are a number which tease the law’s capacity to respond to new offences. These include complex problems arising largely from the ease with which data, software, or music may be copied. The pillars upon which intellectual property law was constructed have been shaken. This incorporates the law of patents and trademarks, especially in respect of domain names. Defective software gives rise to potential contractual and tortious claims for compensation. The storage of data on mobile telephones and other devices persistently tests the law’s ability to protect the innocent against the ‘theft’ of information. New threats emerge almost daily.

Criminals have not been slow to exploit the law’s frailties. Cybercrime poses new challenges for criminal justice, criminal law, and law enforcement both nationally and internationally. Innovative online criminals generate major headaches for police, prosecutors, and courts. This new terrain incorporates cybercrimes against the person (such as cyberstalking and cyberpornography), and cybercrimes against property (such as hacking, viruses, causing damage to data), cyberfraud, identity theft, and cyberterrorism. Cyberspace provides organized crime with more sophisticated and potentially more secure methods for supporting and developing networks for a range of criminal activities, including drug and arms trafficking, money laundering, and smuggling.

Some wrongs have simply undergone a digital rebirth. For example, the tort of defamation has found a congenial new habitat in cyberspace. The law in most jurisdictions protects the reputation of persons through the tort of defamation or its equivalent. It will be recalled that while there are variations within common law jurisdictions, the law generally imposes liability where the defendant intentionally or negligently publishes a false, unprivileged statement of fact that harms the plaintiff’s reputation. Civil law systems, instead of recognizing a separate head tort of defamation, protect reputation under the wing of rights of the personality. In cyberspace, however, national borders tend to disintegrate, and such distinctions lose much of their importance.

The advent of email, Facebook, Twitter, bulletin boards, newsgroups, and blogs provide fertile ground for defamatory statements online. Since the law normally requires publication to only one person other than the victim, an email message or posting on a newsgroup will suffice to found liability. But it is not merely the author of the libel who may be liable.

Law in a precarious world

As it unfolds, the 21st century yields few reasons to be cheerful. Our world continues to be blighted by war, genocide, poverty, disease, corruption, bigotry, and greed. More than one-sixth of its inhabitants—over a billion people—live on less than $1 a day. Over 800 million go to bed hungry every night, representing 14 per cent of the world’s population. The United Nations estimates that hunger claims the lives of about 25,000 people every day. The relationship between poverty and disease is unambiguous. In respect of HIV/AIDS, for example, 95 per cent of cases occur in developing countries. Two-thirds of the forty million people infected with HIV live in sub-Saharan Africa.

Amid these gloomy statistics, occasional shafts of light appear to justify optimism. There has been some progress in diminishing at least some of the inequality and injustice that afflict individuals and groups in many parts of the world. And this has been, in no small measure, an important achievement of the law. It is easy, and always fashionable, to disparage the law, and especially lawyers, for neglecting—or even aggravating—the world’s misery. Yet such cynicism is increasingly unfounded in the light of the progress, albeit lumbering, in the legal recognition and protection of human rights.

The adoption by the United Nations, in the grim shadow of the Holocaust, of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, and the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights, and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 1976, demonstrates, even to the most sceptical observer, a commitment by the international community to the universal conception and protection of human rights. As mentioned earlier, this so-called International Bill of Rights, with its inevitably protean and slightly kaleidoscopic ideological character, reflects an extraordinary measure of cross-cultural consensus among nations.

The idea of human rights has passed through three generations. The first generation consisted of mostly ‘negative’ civil and political rights. A right is negative in the sense that it entails a right not to be interfered with in certain prohibited ways, for example my right to speak freely. A right is positive, on the other hand, when it expresses a claim to something such as education or health or legal representation. These second-generation rights crowd under the umbrella of economic, social, and cultural rights.

The third generation of rights comprises primarily collective rights which are foreshadowed in Article 28 of the Universal Declaration, which declares that ‘everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized’. These ‘solidarity’ rights include the right to social and economic development and to participate in and benefit from the resources of the earth and space, the right to scientific and technical information (which are especially important to the Third World), and the right to a healthy environment, peace, and humanitarian disaster relief (see Figure 12).

It is sometimes contended that unwarranted primacy is given to positive rights at the expense of negative rights. The latter, it is argued, are the ‘genuine’ human rights, since without food, water, and shelter, the former are a luxury. The reality, however, is that both sets of rights are equally important. Democratic governments that respect free speech are more likely to address the needs of the poor. On the other hand, in societies where economic and social rights are protected, democracy has an enhanced prospect of success since people are not preoccupied with concerns about their next meal.

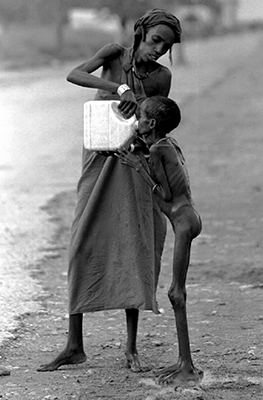

12. Severe poverty afflicts millions of people around the world.

Misgivings surrounding the concept of human rights are not new. Qualms are expressed by those who perceive the expanding recognition of human rights as undermining the ‘war on terror’. Still others find many of the rights expressed in declarations to be incoherent or cast in such vague and general terms, and weakened by inevitable exclusions and exemptions, that often they appear to take away with one hand what they give with the other. In impoverished countries, modern conceptions of human rights are at times regarded with suspicion as Western or Eurocentric, failing to address the problems of starvation, poverty, and suffering that afflict many of their people. Indeed, it is asserted that they merely shore up the prevailing distribution of wealth and power.

These, and many other, doubts about the development of human rights are not to be lightly dismissed. Nor should we be under any illusion that international, or indeed domestic, declarations or the agencies that exist to implement them are adequate. They provide the contours of a strategy for improved protection. The role of the numerous NGOs, independent human rights commissions, pressure groups, and courageous individuals are of paramount importance. The growing body of law on the subject does promote a degree of optimism about the future well-being of humanity. In view of our planet’s ecological despoliation and even potential nuclear immolation, it is necessary, if not essential, to conceive of rights as a weapon by which to safeguard the interests of all living things against harm, and to promote the circumstances under which they are able to flourish.

A fundamental shift in our social and economic systems and structures may be the only way in which to secure a sustainable future for our world and its inhabitants. The universal recognition of human rights seems to be a vital element in this process.

The future will undoubtedly challenge the capacity of the law not only to control domestic threats to security, but also to negotiate a rational approach to the menace of international terror. Public international law and the United Nations Charter will continue to offer the optimal touchstone by which to determine what constitutes tolerable conduct in respect of both war and peace. ‘Humanitarian intervention’ has in recent years become a significant feature of the international scene. There is increasing support for action to prevent or avoid the horrors of gruesome flashpoints around the world. The list seems to grow almost daily. Moreover, in a world in which the law must confront an insidious enemy within, the very foundations of international law are severely tested. This war is waged not between states, but by a clandestine international terrorist network with pernicious ambitions.

It is easy, especially for lawyers, to exaggerate the significance of the law. Yet history teaches that the law is an essential force in facilitating human progress. This is no small achievement. Without law, as Thomas Hobbes famously declared:

there is no place for Industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth, no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious Building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth, no account of Time, no Arts, no Letters, no Society; and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of people, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

If we are to survive the calamities that await us, if civilized values and justice are to prevail and endure, the law is surely indispensable.