In 1994 I drank my first lassi at Dipti’s Pure Drinks in the Colaba area of Bombay. Its thick, velvety sweetness was seductive. During my stay in the city I kept returning for more. I also ate my first vegetarian thali in a working-men’s eatery, and wondered about the state of the kitchens when a rat sat on my foot.

At the home of John and Susan Gnanasundaram in Madras I discovered the delights of Indian home cooking: spongy idlis with freshly made, bright green, sharp coriander chutney for breakfast, and rich chicken curries for dinner. None of it tasted like the Indian food I was used to in British Indian restaurants.

A few months later I became very ill with cholera. While I was recovering, I could only manage to eat tea and toast; I also discovered that tourist hotels still served the food of the Raj and I recuperated on a diet of yellow omelettes. It was when I was feeling better that I sampled mulligatawny soup at an expensive Delhi hotel restaurant, surrounded by the left-over trappings of the Raj – cane chairs and potted palms. The soup was sour and hot and I thought it was horrible. But my interest in the British relationship with Indian food was established.

I returned to Britain and wrote my first book which was about the British body in India. It traced the changing way in which the British managed, disciplined and displayed their bodies as their position in India moved from commerce to control and imperialism. Part of this process was their rejection of Indian curries in favour of tinned salmon and bullety bottled peas.

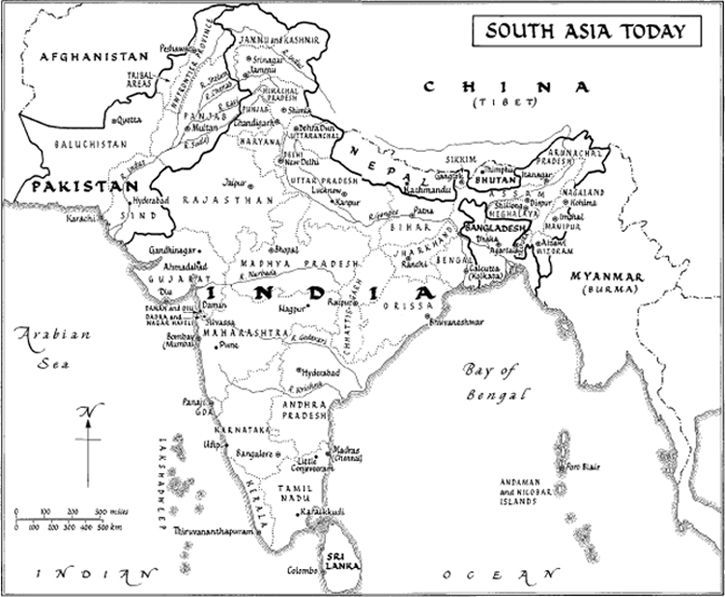

The British relationship with Indian food continued to capture my imagination and, while researching this book, I was surprised to discover that tea was probably the most important item of food or drink that the British bequeathed to India, hence my chapter on chai. Most of this book, however, is an exploration of the histories of many of the Indian dishes familiar to habitués of Indian restaurants. I trace their culinary roots, their discovery, or invention, by Europeans and the various ways in which they travelled back to Britain, and around the rest of the world. It is a biography of the curries of the Indian subcontinent, as defined by the nations of Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. (I have omitted Malaysian and Thai curries which carry with them a different history.)

Lizzie Collingham,