POEMS AND BALLADS

A Ballad of Life and A Ballad of Death

Swinburne relished the most lurid accounts of Lucrezia Borgia’s cruelty and sexual adventurousness, as in Victor Hugo’s Lucrèce Borgia (1833), which he read at Eton, and Alexandre Dumas’s Crimes Célèbres (1839-1842). He would also have known of Byron’s theft of a strand of her hair and the poem by Landor which it inspired, ‘On Seeing a Hair of Lucretia Borgia’ (1825, 1846). In the early 1860s he had written part of a projected long story about Borgia; Randolph Hughes, who edited the fragment in 1942, sifts through the evidence for Swinburne’s sources for that work. The two poems open Poems and Ballads with Swinburne’s favourite femme fatale and, in addition, introduce the volume as a whole; the roses in the envoy to the first poem refer to the poems in the collection.

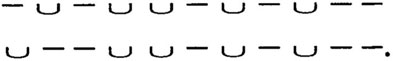

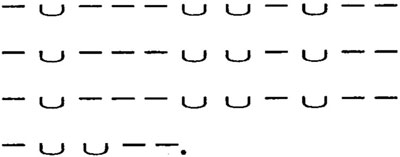

A central figure in the brilliant court at Ferrara, Borgia had received sophisticated verse in her praise (from Bembo and Ariosto among others). Swinburne’s two poems are ‘Italian canzoni of the exactest type’, in the words of William Rossetti, who adds that they have taken ‘the tinge which works of this class have assumed in Mr. Dante G. Rossetti’s volume of translations The Early Italian Poets [1861]’. That is, they consist of several stanzas in a rhyme scheme which is unique to each poem, include both pentameter and trimeter lines, and conclude with an envoy. Rossetti’s drawing of a woman playing a lute surrounded by three lecherous men, a work that evolved into his watercolour of Borgia, has also been adduced as an influence (cf. Virginia Surtees’ catalogue raisonné of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s paintings and drawings, catalogue numbers 47 and 48).

The rhyme ‘moon’ and ‘swoon’ (lines 5–6, ‘A Ballad of Life’) occurs in Tennyson’s ‘Fatima’ (1832), an adaptation of Sappho. For the blue eyelids (line 8, ‘A Ballad of Life’) as a sign of either fatigue or pregnancy, see Leah Marcus, Unediting the Renaissance, 1996, pp. 5–17. The phrase ‘whole soul’ (line 65, ‘A Ballad of Life’) is common in Tennyson and Browning as well as in Swinburne; it occurs twice in ‘Fatima’. ‘Sendaline’ (line 41, ‘A Ballad of Death’) is sendal, a thin rich silken material (the OED cites Swinburne alone for the form ‘sendaline’). The phrase ‘who knows not this’ (cf. line 86, ‘A Ballad of Death’) appears in Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (Night II, line 386) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s translation of a sonnet by Bonaggiunta Urbiciani, da Lucca, ‘Of Wisdom and Foresight’ (1861).

The diction is frequently biblical: for example, ‘righteous’ (line 70, ‘A Ballad of Life’), ‘lift up thine eyes’ (line 54, ‘A Ballad of Death’), ‘vesture’ (line 79, ‘A Ballad of Death’). ‘Honeycomb’, ‘spikenard’, and ‘frankincense’ (lines 64–7, ‘A Ballad of Death’) appear in the Song of Solomon. Swinburne’s diction throughout the collection is influenced by the Authorized Version; I have usually given references only in cases of allusion. In 1876, Swinburne planned to ‘subjoin in the very smallest capitals’ the words ‘In honorem D. Lucretiae Estensis Borgiae’ and ‘In obitum D. Lucretiae Estensis Borgiae’ under the titles of the respective poems (Lang, 3, 200).

Some copies of the 1904 Poems print ‘curled air’ rather than ‘curled hair’ (‘A Ballad of Death’, line 36).

Laus Veneris

The ‘Praise of Venus’ is Swinburne’s adaptation of the Tannhäuser legend, which emerged shortly after the time of the minnesinger’s death (c. 1270) in an anonymous ballad that tells the story of the knight who had been living in Venus Mountain but who, sated with pleasure, feels remorse and travels to Rome in order to obtain absolution. The pope, leaning on a dry dead staff, tells him that it will sprout leaves before the poet receive God’s grace. Swinburne’s fictitious French epigraph takes up the story at this point:

Then he said weeping, Alas, too unhappy a man and a cursed sinner, I shall never see the mercy and pity of God. Now I shall go from here and hide myself within Mount Horsel [Venus Mountain], entreating my sweet lady Venus of her favour and loving mercy, since for her love I shall be damned to Hell for all eternity. This is the end of all my feats of arms and all my pretty songs. Alas, too beautiful was the face and the eyes of my lady, it was on an evil day that I saw them. Then he went away groaning and returned to her, and lived sadly there in great love with his lady. Afterward it happened that the pope one day saw fine red and white flowers and many leafy buds break forth from his staff, and in this way he saw all the bark become green again. Of which he was much afraid and moved, and he took great pity on this knight who had departed without hope like a man who is miserable and damned. Therefore he sent many messengers after him to bring him back, saying that he would have God’s grace and good absolution for his great sin of love. But they never saw him; for this poor knight remained forever beside Venus, the high strong goddess, in the amorous mountainside.

Book of the great wonders of love, written in Latin and French by Master Antoine Gaget. 1530.

The story was popular among German Romantic writers. Ludwig Tieck introduced it in his story ‘Der getreue Eckart und der Tannhäuser’ (1799); Swinburne may have read the translation Thomas Carlyle made in 1827. The ballad itself became well known early in the century when it was printed in a collection of folksongs in 1806 and retold later by Grimm; Clemens Brentano, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Joseph von Eichendorff, Franz Grillparzer, and others also made use of it. Heinrich Heine’s poem ‘Der Tannhäuser. Eine Legende’ (1847) was a source for Wagner’s opera, which Baudelaire defended in La Revue européenne after its first performance in Paris in 1861. However, neither Wagner nor Baudelaire’s comment were direct sources for Swinburne; at most he could have read about the opera, and he received Baudelaire’s pamphlet only after he had written the poem. (See, however, Anne Walder, Swinburne’s Flowers of Evil, 1976, p. 88.) Swinburne may have known William Morris’s ‘The Hill of Venus’ (published in 1870 in The Earthly Paradise but according to his daughter written in the early sixties).

Clyde Hyder in ‘Swinburne’s Laus Veneris and the Tannhäuser Legend’ (PMLA, 45:4, December 1930, 1202–13) sorts out the different cases for influences and sources, one of which he identifies as a translation of the Tannhäuser ballad that appeared in the newspaper Once a Week on 17 August 1861. For Burne-Jones’s paintings of the subject (the earliest begun in 1861, the most famous painted in 1873–8) and their relation to Swinburne, see Kirsten Powell, ‘Burne-Jones, Swinburne, and Laus Veneris’ (in Pre-Raphaelitism and Medievalism in the Arts, ed. Liana Cheney, 1992). While visiting Fantin-Latour’s studio in Paris in 1863, Swinburne saw a sketch of the Tannhäuser in the Venusberg. J. W. Thomas in Tannhäuser: Man and Legend (1974) provides information about Tannhäuser, the legend, and its later uses.

The poem is a dramatic monologue written in the stanza Edward Fitz-Gerald used to translate the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1859); Swinburne, however, links pairs of stanzas by rhyming their third lines. In the poem, Venus has survived into the Middle Ages, but her stature has been diminished; nonetheless, we have glimpses of her former power both in its destructive aspect (lines 117–37, for example, include Adonis, the favourite of Aphrodite, killed by a boar) and in her incarnation as Venus Anadyomene, rising from the sea (lines 389–92).

Swinburne’s vision of hell is indebted to Dante’s second circle of hell, reserved for lustful sinners. Helen, Cleopatra, and Semiramis in lines 193–204 recall the sequence Semiramis, Cleopatra, and Helen in Inferno 5: 52-63. Swinburne’s description of Semiramis draws loosely on Assyrian art, knowledge of which, thanks to Henry Layard and the British Museum, had entered both popular culture and works by Tennyson and Rossetti. The line immediately following the description of the lustful sinners in Swinburne, ‘Yea, with red sin the faces of them shine’ (line 205), is modelled on the line ‘culpa rubet vultus meus’ from ‘Dies Irae’, as Lafourcade points out.

‘Great-chested’ in line 204 does not appear in the OED, but ‘deep-chested’ occurs in Landor, Tennyson and Longfellow. For the ‘long lights’ of line 216, cf. the ‘long light’ of Tennyson’s The Princess (1847; the song between Parts 3 and 4). ‘Doubt’ in line 252 means ‘suspect’, and ‘teen’ in that line means ‘grief’. ‘Slotwise’ in line 267, for which the OED gives Swinburne as the first citation, is derived from ‘slot’, the track of an animal. ‘Springe’ and ‘gin’ in lines 271–2 are both snares, the latter in this case for men. ‘Vair’ in line 278 is fur from squirrel. The elder-tree of line 305 is the European Sambucus nigra and not the American Sambucus canadensis, which does not grow large. ‘To save my soul alive’ (line 331) resembles Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s line ‘To save his dear son’s soul alive’ in ‘Sister Helen’, line 192 (1853, 1857, 1870; see also his translation of Cavalcanti’s sonnet to Pope Boniface VIII, 1861, line 13). It derives from Ezekiel 18:27. ‘Wizard’ in line 338 is an adjective meaning ‘bewitched’ or ‘enchanted’. Lines 369-70 recall James Shirley’s couplet ‘Only the actions of the just / Smell sweet, and blossom in their dust’, from one of his most famous lyrics, ‘The glories of our blood and state’, at the end of The Contention of Ajax and Ulysses.

‘Explicit’ in the closing formula is a medieval Latin word which came to be regarded as a verb in the third person singular, meaning ‘here ends’ (a book, piece, etc.). It was current until the sixteenth century.

See ‘Notes on Poems and Reviews’ (Appendix 1) for Swinburne’s own discussion of the poem. William Empson discusses lines 49–56 in Seven Types of Ambiguity, 3rd ed. 1953, pp. 163–5.

There is a reproduction of the first four stanzas of a manuscript of ‘Laus Veneris’ in Wise’s 1919 Bibliography.

Phædra

Euripides, Seneca and Racine wrote the major extant dramas about Hippolytus and Phaedra, but the combination of masochism and sexual aggressiveness in Swinburne’s Phaedra is not derived from his models. Despite his contempt for Euripides and very limited esteem of Racine, he includes a discriminating comparison of Hippolytus and Phèdre in his essay on Philip Massinger (1889; reprinted in Contemporaries of Shakespeare, pp. 201–2).

Hippolytus, the son of Theseus and the Amazon Hippolyta (line 56), has been raised by Theseus’s grandfather Pittheus (line 176) in Troezen, a town in the Peloponnese. Phaedra is the daughter of King Minos of Crete and Pasiphae (line 35; Pasiphae is the daughter of the sun, line 53). She is the wife of Theseus, who marries her after his most famous exploit: killing the minotaur, the offspring of Pasiphae by a handsome bull, and thus the half-brother of Phaedra (line 181). King Minos had regularly fed it a tribute of Athenian youth (cf. lines 179–81), but Theseus defeats it and escapes from the labyrinth that contained it with the help of Ariadne, Phaedra’s sister; he leaves Crete with Ariadne but later abandons her and marries Phaedra. He rules in Athens but is obliged to move temporarily to Troezen, where Aphrodite, revenging herself on Hippolytus for his excessive devotion to Artemis, inspires Phaedra to love her stepson passionately. In most versions of the story, Theseus has been away from Troezen for a time (consulting an oracle or waiting for Heracles to release him from hell).

‘Have’ in line 5 is in the subjunctive mood. The comparison of grass and the colour of flesh (line 27) recalls Sappho (φα νεταí μοι), and the periphrastic address to divinity in lines 29–30 is like Aeschylus, Agamemnon, lines 160–2. Line 47 echoes Christ’s words ‘Woman, what have I to do with thee?’ (John 2:4). The evil born with all its teeth (line 73) recalls Richard III (see Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part 3, Act 5, Scene 6). ‘Ate’ (line 139) is the passionate derangement of the mind and senses that leads to ruin. Amathus (line 139), on Cyprus, is the site of a famous shrine to Aphrodite. ‘Lies’ (line 155) are strata or layers, masses that lie, according to the OED, which cites Swinburne’s usage. The sea is hollow (line 165) when the troughs between waves are very deep.

νεταí μοι), and the periphrastic address to divinity in lines 29–30 is like Aeschylus, Agamemnon, lines 160–2. Line 47 echoes Christ’s words ‘Woman, what have I to do with thee?’ (John 2:4). The evil born with all its teeth (line 73) recalls Richard III (see Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part 3, Act 5, Scene 6). ‘Ate’ (line 139) is the passionate derangement of the mind and senses that leads to ruin. Amathus (line 139), on Cyprus, is the site of a famous shrine to Aphrodite. ‘Lies’ (line 155) are strata or layers, masses that lie, according to the OED, which cites Swinburne’s usage. The sea is hollow (line 165) when the troughs between waves are very deep.

Swinburne’s note to line 97 signals that the next six lines are a translation of a fragment of Niobe, a lost play by Aeschylus:

(‘Death alone of all gods does not love gifts, neither by sacrifice nor by libation would you accomplish anything, he has no altar nor is he praised; from him alone among gods, does Persuasion stand apart.’ The text is taken from Dindorf’s 1851 Poetae Scenici Graeci.)

For possible echoes from Beaumont and Fletcher’s Maid’s Tragedy, see Mario Praz, ‘Le Tragedie “Greche” di A. C. Swinburne’, Atene e Roma, No. 7–8–9 (July–August–September 1922), p. 185n2.

The poem, in blank verse, is an imitation of an episode of Greek tragedy; the use of stikhomythia (one- or two-line exchanges between characters) and the oblique naming of a divinity (lines 29–30) are characteristic of Greek tragedy.

The Triumph of Time

Recent biographers have interpreted ‘The Triumph of Time’ as a cri de coeur provoked by the engagement of Swinburne’s greatest romantic interest, his cousin Mary Gordon, to Colonel Robert Disney Leith, who was twenty-one years older than she was.

The ‘sea-daisies’ (line 56) are also known as sea-pinks. The ‘third wave’ (line 83) derives from the Greek τρικνμ α, originally meaning a group of three waves; later it comes to mean a large or irresistible wave (cf. Prometheus Bound, line 1015, Euripides’ Hippolytus, line 1213, Plato’s Republic, 472a). The OED credits Swinburne with the first citation for this meaning of ‘third’. ‘Flesh of his flesh’ (line 102) is an adaptation of Genesis 2:23. The narrow gate of line 168 recalls Matthew 7:13–14 and Luke 13:24, where it leads to life. The pleonastic phrase ‘royal king’s’ (line 220) may be an echo of ‘royal kings’ in Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra (Act V, Scene 2, line 326). Line 223 may recall ‘What hath night to do with sleep’ of Milton’s ‘Comus’ (line 122). The quotation in line 237 is from Hamlet’s lines to Ophelia beginning ‘Get thee to a nunnery’ (Act 3, Scene 1). Line 253 is indebted to Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s ‘The Blessed Damozel’ (1850, 1856, 1870), ‘And the stars in her hair were seven’ (line 6). Line 273 is similar to Tennyson’s Maud (1855), ‘But only moves with the moving eye’ (Part II, line 85). The ‘midland sea’ (line 322) is the Mediterranean. ‘Or ever’ (line 332) is emphatic for ‘before’. ‘Overwatching’ (line 374) can mean both ‘keeping watch over’ and ‘fatiguing by excessive watching’.

α, originally meaning a group of three waves; later it comes to mean a large or irresistible wave (cf. Prometheus Bound, line 1015, Euripides’ Hippolytus, line 1213, Plato’s Republic, 472a). The OED credits Swinburne with the first citation for this meaning of ‘third’. ‘Flesh of his flesh’ (line 102) is an adaptation of Genesis 2:23. The narrow gate of line 168 recalls Matthew 7:13–14 and Luke 13:24, where it leads to life. The pleonastic phrase ‘royal king’s’ (line 220) may be an echo of ‘royal kings’ in Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra (Act V, Scene 2, line 326). Line 223 may recall ‘What hath night to do with sleep’ of Milton’s ‘Comus’ (line 122). The quotation in line 237 is from Hamlet’s lines to Ophelia beginning ‘Get thee to a nunnery’ (Act 3, Scene 1). Line 253 is indebted to Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s ‘The Blessed Damozel’ (1850, 1856, 1870), ‘And the stars in her hair were seven’ (line 6). Line 273 is similar to Tennyson’s Maud (1855), ‘But only moves with the moving eye’ (Part II, line 85). The ‘midland sea’ (line 322) is the Mediterranean. ‘Or ever’ (line 332) is emphatic for ‘before’. ‘Overwatching’ (line 374) can mean both ‘keeping watch over’ and ‘fatiguing by excessive watching’.

The ‘singer in France of old’ (line 321) is the troubadour Jaufre Rudel, who lived in the south of France in the twelfth century. His thirteenth-century vida explains:

Jaufre Rudel, Prince of Blaye, was a very noble man. And he fell in love with the Countess of Tripoli, without having seen her, because of the great goodness and courtliness which he heard tell of her from the pilgrims who came from Antioch. And he wrote many good songs about her, with good melodies and poor words. And because of his desire, he took the cross and set sail to go to see her. But in the ship he fell very ill, to the point where those who were with him thought he was dead. However, they got him – a dead man, as they thought – to Tripoli, to an inn. And it was made known to the Countess, and she came to his bedside, and took him in her arms. And he knew she was the Countess, and recovered sight [or, hearing] and smell, and praised God because He had kept him alive until he had seen her. And so he died in the arms of the lady. And she had him buried with honour in the Temple at Tripoli. Then, the same day, she became a nun because of the grief which she felt for him and for his death.

(George Wolf and Roy Rosenstein, The Poetry of Cercamon and Jaufre Rudel, 1983. See also The Vidas of the Troubadours, Margarita Egan, 1984.)

The story of this troubadour is present elsewhere in nineteenth-century literature; we find it in Stendhal (in De l’amour, 1822), Heine (in Romanzero, 1851), and Browning (‘Rudel and the Lady of Tripoli’, 1842). The story remains current after Swinburne: Carducci, Rostand, Pound and Döblin were drawn to it. Swinburne’s ‘The Death of Rudel’, apparently written during his college years, is printed in the first volume of the Bonchurch edition of his works.

The stanza consists of tetrameter lines of both iambs and anapests and rhymes ababccab; it is the same stanza used for the first choral ode of Atalanta in Calydon. George Saintsbury, in A History of English Prosody (1906, Vol. 3, p. 233), sees ‘The Triumph of Time’ as an improvement, prosodically and otherwise, on Browning’s ‘The Worst of It’ (1864). The title derives ultimately from Petrarch’s allegorical Trionfi (his ‘Triumph of Love’ mentions Rudel). There are triumphs of time by Robert Greene (Swinburne praised his prose romance Pandosto, The Triumph of Time in 1908), Beaumont and Fletcher, and Handel.

Cecil Lang, in ‘A Manuscript, a Mare’s-Nest, and a Mystery’ (Yale University Library Gazette, Vol. 31, 1957, pp. 163–71), prints an early fragment of the poem. The first page of the poem in manuscript is reproduced in Rooksby, p. 104.

Les Noyades

For a time, the noyade was as famous as the guillotine, both being methods of mass execution introduced during the French Revolution. Jean-Baptiste Carrier arrived in Nantes in October 1793 as the representative of the Committee of Public Safety to control the insurrection in the Vendée. He soon introduced the mass drownings of prisoners, who were confined to boats that were then sunk in the Loire. He was recalled to Paris in February 1795 and eventually tried and executed. Among the charges he faced were ‘republican marriages’, the binding of a naked man and woman together before they were drowned. Some historians have subsequently disputed that any republican marriages actually occurred, but at the time it was sensational news. James Schmidt, in a discussion of the noyade in the development of Hegel’s thought (‘Cabbage Heads and Gulps of Water’, Political Theory, 26:1, February 1998, pp. 4–32), sets out the historical background of Carrier’s activities and also reproduces a contemporary illustration of the republican marriages.

Swinburne probably knew Carlyle’s French Revolution (1837), Part 3, Book 5, Chapter 3:

Nantes town is sunk in sleep; but Représentant Carrier is not sleeping, the wool-capped Company of Marat is not sleeping. Why unmoors that flatbottomed craft, that gabarre; about eleven at night; with Ninety Priests under hatches? They are going to Belle Isle? In the middle of the Loire stream, on signal given, the gabarre is scuttled; she sinks with all her cargo. ‘Sentence of deportation’, writes Carrier, ‘was executed vertically’. The Ninety Priests, with their gabarre-coffin lie deep! It is the first of the Noyades, what we may call Drownages, of Carrier; which have become famous forever…

Or why waste a gabarre, sinking it with them? Fling them out; fling them out, with their hands tied; pour a continual hail of lead over all the space, till the last struggler of them be sunk! Unsound sleepers of Nantes, and the Sea-Villages thereabouts, hear the musketry amid the night-winds; wonder what the meaning of it is. And women were in that gabarre; whom the Red Nightcaps were stripping naked; who begged, in their agony, that their smocks not be stript from them…

By degrees, daylight itself witnesses Noyades: woman and men are tied together, feet and feet, hands and hands; and flung in: this they call Manage Républicain, Republican Marriage.

‘Mean’ (line 53) refers to the speaker’s inferior social rank. The poem is in rhyming quatrains (abab) of tetrameter lines of both iambs and anapests.

A Leave-Taking

‘All we’ (lines 5 and 20): formerly used for ‘we all’ or ‘all of us’ (OED, ‘all’, 2c). ‘Thrust in thy sickle and reap’ (line 18) echoes Revelation 14:15.

Cecil Lang (‘A Manuscript, A Mare’s-Nest, and A Mystery’, Yale University Library Gazette, Vol. 31, 1957, pp. 163–71) publishes early drafts of the poem.

Each stanza rhymes aababaa; the a rhyme of one stanza becomes the b rhyme of the next. Swinburne modifies such forms as the rondeau and its relatives or the villanelle, which have the same two rhymes throughout an entire poem. In other ways, too, the poem recalls early French stanza forms: it has a refrain, like the ballade or chant royal (though the last word of the refrain changes), and the shortness of the refrain is like the rentrement of a rondeau, though here it responds to the second half of the first line of the stanza rather than the first half. It is suggestive of the French formes fixes without being directly imitative of them.

Itylus

The poem is a monologue by Philomela, the sister of Procne, who is the wife of Tereus, the king of Thrace (line 48). He lusts after Philomela, rapes her, and then cuts off her tongue and hides her. Philomela tells her story by weaving the events in the design of a tapestry (line 52), which she sends to Procne. The sisters revenge themselves by killing Itylus, the son of Tereus and Procne, and cooking him. Procne feeds him to Tereus and afterwards reveals what they have done; Tereus pursues them in a rage, but they are saved by the gods, who turn Philomela into a nightingale (line 19) and Procne into a swallow.

In Daulis (line 48), in central Greece, the women murdered Itylus, according to Thucydides (ii. 29). Swinburne appears to locate it on the Thracian coast, perhaps mistaking a detail from Matthew Arnold’s ‘Philomela’ (1853). The wet roofs and lintels (line 51) may suggest the blood of Itylus; cf. Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book 6, line 646 (‘manant penetralia tabo’, ‘the room drips with gore’). ‘Itylus’ is the name in Homer; ‘Itys’ is more common. In Greek poetry, it is Procne who becomes the nightingale.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book 6, is the major source of the story. There are references to it in Homer (Odyssey, Book 19, lines 518–523), Aeschylus (Agamemnon, lines 1140–9 and Suppliants, lines 58–67), and Apollodorus. In addition to Matthew Arnold, Catulle Mendès was inspired by the legend; see ‘Le Rossignol’ in Philoméla (1863), which appeared shortly before Swinburne wrote his poem.

Swinburne combines iambs and anapests in stanzas of six tetrameters rhyming abcabc. ‘Swallow’ is a constant feminine rhyme in each stanza.

Anactoria

Swinburne’s admiration for Sappho was unbounded. In a posthumously published appreciation (‘Sappho’, The Saturday Review, 21 February 1914, p. 228) he wrote:

Judging even from the mutilated fragments fallen within our reach from the broken altar of her sacrifice of song, I for one have always agreed with all Grecian tradition in thinking Sappho to be beyond all question and comparison the very greatest poet that ever lived. Æschylus is the greatest poet who ever was also a prophet; Shakespeare is the greatest dramatist who ever was also a poet; but Sappho is simply nothing less – as she is certainly nothing more – than the greatest poet who ever was at all. Such at least is the simple and sincere profession of my lifelong faith.

(See also Lang, 4, 124 and Swinburne’s defence of the poem in ‘Notes on Poems and Reviews’, Appendix 1.)

Her ode beginning ‘φα νεταí μοι’, known to Swinburne as the ‘Ode to Anactoria’, provides the context of this poem: Sappho suffers intense erotic jealousy because of Anactoria’s infidelity to her. In Swinburne’s dramatic monologue, Sappho addresses Anactoria in an attempt to win her back. He works some of Sappho’s own words into the address. (The standard text of Sappho at the time was Theodor Bergk’s Poetae Lyrici Graeci, revised in 1853; citations to Bergk’s edition are accompanied by those to the Loeb text, edited and translated by David A. Campbell, Greek Lyric, volume 1.)

νεταí μοι’, known to Swinburne as the ‘Ode to Anactoria’, provides the context of this poem: Sappho suffers intense erotic jealousy because of Anactoria’s infidelity to her. In Swinburne’s dramatic monologue, Sappho addresses Anactoria in an attempt to win her back. He works some of Sappho’s own words into the address. (The standard text of Sappho at the time was Theodor Bergk’s Poetae Lyrici Graeci, revised in 1853; citations to Bergk’s edition are accompanied by those to the Loeb text, edited and translated by David A. Campbell, Greek Lyric, volume 1.)

line 63: ‘For I beheld in sleep’; cf. ‘In a dream I spoke with the Cyprus-born’ (Bergk 86; Campbell 134).

line 70: ‘a mind of many colours’; translates πoικíλοφρov, found in the first line of some texts of the Aphrodite ode.

lines 73–4: ‘Who doth thee wrong, Sappho?’ translates lines 19–20 of the Aphrodite ode.

lines 81–4 are a translation of the sixth stanza of the Aphrodite ode.

lines 189–200 are an expansion of Bergk 68, Campbell 55.

line 221: ‘sleepless moon’ conflates the moon and the sleepless speaker of one of the most famous fragments, though now denied by many to Sappho; Bergk 52, Campbell 168B.

In addition, Sappho’s boasts that she will be remembered after death have been amplified in lines 203–14. The names Erinna (line 22) and Atthis (line 286) occur in some fragments. The name ‘Erotion’ (line 22) presumably refers to a male lover; see the note to Swinburne’s poem ‘Erotion’. Lines 260–5 allude to the legend of Sappho’s suicide by drowning as the result of an unhappy love affair with Phaon.

The epigraph is an emendation, perhaps Swinburne’s own, of a corrupt line in the Aphrodite ode; Swinburne’s version means ‘Whose love have you caught in vain by persuasion?’ (Sappho calls Persuasion the daughter of Aphrodite; see Bergk 133, Campbell 200.)

‘Reluctation’ (line 33) means ‘struggle, resistance, opposition’ (OED: ‘somewhat rare’; ‘obsolete’ with reference to bodily organs). Aphrodite’s ‘amorous girdle’ (line 45) makes her irresistible; in lines 49–50, we are given the account of her birth from the ocean (Aphrodite Anadyomene); Paphos, line 64, is the site of her famous sanctuary on Cyprus. ‘Storied’ (line 68) means either ‘ornamented with scenes from history or legend’ or ‘celebrated in history or story’. ‘Flies’ (line 81) means ‘flees’. Swinburne activates the etymology of ‘disastrous’ in ‘disastrous stars’ (line 164); ‘comet’ and ‘hair’ (lines 161–2) are also connected etymologically. Pieria is a district in Thessaly associated with the Muses, and so the ‘high Pierian flower’ (line 195) is a poem as well as the garland for the victorious poet. ‘Reflex’ (line 198) is a reflection of light. In line 302, the lotus produces dreamy forgetfulness, and Lethe is the river of oblivion.

Timothy A. J. Burnett, in ‘Swinburne at Work: The First Page of “Anactoria” ’ (in The Whole Music of Passion, eds Rikky Rooksby and Nicholas Shrimpton, 1993), discusses and reproduces a draft of the first page of the poem. It is also reproduced in Yopie Prins, Victorian Sappho (1999), p. 118. Edmund Gosse discusses a first version of the poem in ‘The First Draft of Swinburne’s “Anactoria” ’ (Modern Language Review, 14, 1919, pp. 271–7).

The poem is in heroic couplets; all sentences come to a stop at the end of a line.

Hymn to Proserpine

Constantine I, the first Christian Roman emperor, issued the Edict of Milan in 313 with the Eastern Roman emperor Licinus; it established religious toleration of Christians and protected their legal rights. Constantine’s policy went further than official toleration, and he began to establish Rome as a Christian state. His nephew Julian (emperor from 361 to 363) announced his conversion to paganism in 361 and hence is known as Julian the Apostate (see L. M. Findlay, ‘The Art of Apostasy’, Victorian Poetry 28:1, Spring 1990, pp. 69–78, for the Victorian controversies over ‘national apostasy’ and the image of Julian). He became a fierce opponent of Christians, but his opposition had no lasting effect; his legendary dying words (‘Vicisti, Galilaee’, ‘Thou hast conquered, Galilean’) were reported in Greek by Theodoret, the Bishop of Cyrrhus, in the fifth century.

Proserpine, or Persephone, is the wife of Hades and the queen (lines 2, 92) of the underworld; the river Lethe (line 36) and poppies (line 97) are associated with the oblivion of death. She is also Kore, a maiden (lines 2, 92) and the daughter of Demeter, the earth (line 93). She and Demeter are the subject of the mysteries at Eleusis. Swinburne contrasts the new queen of heaven (line 76), the Jewish (line 85, ‘slave among slaves’) virgin (lines 75, 81) mother of Christ, with Venus, the former queen. Venus is described as she rose from the sea (lines 78, 86–9); she is the ‘mother of Rome’ (line 80) both as Aeneas’s mother and as Venus Genetrix; and she is called Cytherean (line 73) after her birthplace in Cythera.

‘I have lived long enough’ (line 1) quotes Macbeth’s line from Act V, Scene 3, line 22. ‘Galilean’ (lines 23, 35, 74) is ‘used by pagans as a contemptuous designation for Christ’ (OED). In Greek ‘unspeakable things’ (line 52, άρρητα) can refer to the Eleusinian mysteries. L. M. Findlay (Swinburne, Selected Poems, 1982, pp. 257–8) suggests that the description of the wave of the world (line 54) is indebted to Turner’s painting The Slave Ship (1834) and Ruskin’s defence of the painting in Modern Painters (1843). ‘Viewless ways’ (line 87) may have been influenced by Shakespeare’s ‘viewless winds’ (Measure for Measure, Act III, Scene 1, line 124) or Keats’s ‘viewless wings’ (‘Ode to a Nightingale’, line 33, 1820). The footnote in Greek by Epictetus is the source of Swinburne’s line 108; the remark survives in Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, 4.41.

Robert Peters (‘A. C. Swinburne’s “Hymn to Proserpine”: The Work Sheets’, PMLA 83, October 1968, pp. 1400–6) discusses the work sheets to the poem and reproduces some of the manuscripts. Bernard Richards (English Verse: 1830–1890, 1980, p. 465) warns that there are errors in Peters’s transcription.

The metre is hexameter with both iambs and anapests. The rhyme is in couplets, and there is an internal rhyme at the end of the third foot. All sentences come to a full stop at the end of a metrical line except for line 105.

Ilicet

‘Ilicet’ is a Latin exclamation of dismay, ‘It’s all over.’

The stooped urn (line 49) is tilted, inclined (the only OED citation for this meaning); to ‘flash’ is to rise and dash, as with the tide. ‘Date’ (line 105) is the ‘limit, term or end of a period of time’ (obsolete or archaic, OED).

For ‘No memory, no memorial’ (line 39), cf. Milton, Paradise Lost Book 1, line 362 and Nehemiah 2:20. ‘Blood-red’ (line 74) is a common colour in Shelley, Tennyson, and Morris. For watching and not sleeping (line 123), cf. 1 Thessalonians 5:6 and recall Gethsemane.

The metre is iambic tetrameter; the six-line stanza rhymes aabccb, where ‘a’ and ‘c’ are feminine rhymes.

Hermaphroditus

Swinburne’s appended note ‘At Museum of the Louvre, March 1863’ indicates that the poem is a response to the Hellenistic sculpture of the sleeping Hermaphrodite, in the Louvre. On the topic of the androgyne and hermaphrodite in this period, see A. J. L. Busst, ‘The Image of the Androgyne in the Nineteenth Century’ in Ian Fletcher’s Romantic Mythologies (1967), and Franca Franchi’s Le Metamorfosi di Zambinella (1991). Busst contrasts the theme of hermaphrodite as the perfection of human existence (the androgynous universal man of the Saint-Simonians and others), current in the first half of the nineteenth century, with the decadent hermaphrodite of the later nineteenth century. The latter was popularized by Henri de Latouche’s once famous Fragoletta (1829); Gautier (Mademoiselle de Maupin, 1836, and ‘Contralto’, 1852), Balzac (Séraphîta, 1835, and La Fille aux yeux d’or, 1835), and Baudelaire (‘Les Bijoux’, 1857) were also influenced by it.

In defence of his choice of subject, Swinburne quotes from Shelley’s description in ‘The Witch of Atlas’ (1820) of the Louvre sculpture; see ‘Notes on Poems and Reviews’ (Appendix 1). For hermaphroditism in Swinburne’s early unpublished Laugh and Lie Down, see Edward Philip Schuldt, Four Early Unpublished Plays of Algernon Charles Swinburne (doctoral dissertation from the University of Reading, 1976), pp. 206–10; he corrects all previous discussions. In Lesbia Brandon, begun in 1864, Swinburne emphasizes the feminine aspects of Herbert Seyton’s appearance and his likeness to his sister (see, for example, pp. 3, 16, 30, 34 and 164 in Hughes’s edition, 1952).

Ovid (Metamorphoses, Book 4) is the main source for the story of Hermaphroditus. Salamacis (line 53), the nymph of a spring, falls in love with him, but he rejects her. She prays that the gods will unite them; the gods do so, forming one being.

For the figurative use of ‘pleasure-house’ (line 24), contrast Tennyson, ‘The Palace of Art’ (1832, 1842): ‘I built my soul a lordly pleasure-house, / Wherein at ease for aye to dwell’ (lines 1–2).

The four sonnets are of the Italian kind, with two quatrains and two tercets. Note that Swinburne only uses four rhymes per sonnet, as Rossetti does occasionally in A House of Love (including several early sonnets). The first three sonnets rhyme abba abba cdc dcd; the last rhymes abba abba cdd ccd.

Fragoletta

William Rossetti writes that the poem ‘has to be guessed at, and is guessed at with varying degrees of horror and repugnance: it is only readers of De Latouche’s novel of the same name who can be certain that they see how much it does, and how much else it does in no wise, mean.’ Latouche’s novel (1829) narrates the story of the hermaphrodite Fragoletta (the name is a diminutive of the Italian word for strawberry and occurs in Casanova and elsewhere); much of the plot is concerned with the complications of bisexual love. Swinburne was dismissive of Latouche’s art, and in A Note on Charlotte Brontë, 1877, he referred to the ‘Rhadamanthine author of “Fragoletta”; who certainly, to judge by his own examples of construction, had some right to pronounce with authority how a novel ought not to be written’; nonetheless, he was more excited in private, as when he wrote that he dare not trust another work of Latouche’s out of his sight (Lang, 1, 46). Swinburne read Gautier’s 1839 review of a drama of the same name as Latouche’s novel, in which he wrote that the ‘Fragoletta est un titre pimpant, égrillard, croustilleux, qui promet beaucoup de choses très-difficile à dire, et surtout à représenter’ (‘Fragoletta is a chic, ribald, spicy title which promises many things very difficult to say and above all to represent’).

The five-line iambic stanza consists of two tetrameters, two trimeters, and a dimeter, rhyming abaab.

Rondel

The rondel is Swinburne’s naturalization of the French rondeau, a fixed form that nonetheless has had many variations. Clément Marot and others established the most common formula: a poem in octosyllabic or decasyllabic lines, consisting of three stanzas made of five, three and five lines respectively. There are only two rhymes, and a refrain (called the rentrement) made from the first half of the first line is added, unrhymed, to the end of the second and third stanzas. Much of the skill of the rondeau is in placing the rentrement in new contexts. The form was popular in the first half of the sixteenth century in France, but was disdained by the Pléiade and long thereafter. Alfred de Musset used it for some of his light verse in the nineteenth century. Théodore de Banville included four rondeaux in his first book, Les Cariatides (1842); Swinburne referred to Banville’s ‘most flexible and brilliant style’ (though one which ‘hardly carries weight enough to tell across the Channel’) in his 1862 essay on Baudelaire.

‘These many years’ is a biblical phrase; see Ezra 5:11, Luke 15:29 (the parable of the prodigal son) and Romans 15:23.

Swinburne adapts the form by using one constant rhyme throughout the poem (in iambic pentameter) and one new rhyme per stanza. The rentrement becomes a rhymed iambic dimeter at the end of each stanza. Two manuscripts of the poem are reproduced in John S. Mayfield’s These Many Years (1947).

Satia Te Sanguine

The title, ‘glut thyself with blood’, derives from the phrase ‘satia te sanguine quem sitisti’ (‘glut thyself with the blood for which thou hast thirsted’), uttered by Queen Tomyris of the Massagetai as she dropped the severed head of Cyrus, the great Persian king who had treacherously killed her son, into a bowl of human blood. The story is recounted by Herodotus (at the end of the first book of his History) and other ancient sources (see Paulys Real-Encyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft, second series); the Latin words are derived from medieval authors like Marcus Junianus Justinus or Paulus Orosius. Tomyris eventually evolves into a virtuous heroine, as in Dante’s Purgatorio, the Speculum humanae salvationis, or Rubens’s painting Queen Tomyris with the Head of Cyrus (see Paget Toynbee, A Dictionary of Proper Names and Notable Matters in the Works of Dante, revised by Charles S. Singleton, 1968, p. 596, and Robert W. Berger, ‘Rubens’s “Queen Tomyris with the Head of Cyrus” ’, Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Vol. 77, 1979, pp 4–35). Swinburne uses the Latin words without alluding to the story and inverts any virtuous connotation they might have. The title and theme are also reminiscent of Baudelaire’s ‘Sed non Satiata’ (1857). Tomyris appears in the procession of women in ‘The Masque of Queen Bersabe’ (p. 176).

For Sappho’s suicide (third stanza), see note to ‘Anactoria’. For line 16, cf. Ezekiel 2:10, ‘and there was written therein lamentations, and mourning, and woe’.

The poem is in quatrains, rhyming abab; the lines are trimeter and combine iambs and anapests.

A Litany

A litany is ‘an appointed form of public prayer, usually of a penitential character, consisting of a series of supplications, deprecations, or intercessions in which the clergy lead and the people respond, the same formula of response being repeated for several successive clauses’ (OED). The poem consists of antiphones (perhaps Swinburne wrote the older form ‘antiphone’ rather than ‘antiphon’ in a mistaken attempt to reproduce the Greek form of the term; the medieval Latin singular ‘antiphona’ comes in fact from the Greek plural τα αντ øωνα). That is, it is to be sung by two voices or choirs. William Rossetti calls the poem ‘a cross between the antiphonal hymnal form and the ideas and phraseology of the Old Testament’. To the influence of the Old Testament, we should add the ideas and phraseology of Revelation. The wine-press of lines 62 and 78 (and likewise ‘that hour’ of line 81) refers to the wrath of God at the Last Judgement; cf. Revelation 14:19–20: ‘And the angel thrust in his sickle into the earth, and gathered the vine of the earth, and cast it into the great winepress of the wrath of God. And the winepress was trodden without the city, and blood came out of the winepress, even unto the horse bridles, by the space of a thousand and six hundred furlongs.’

øωνα). That is, it is to be sung by two voices or choirs. William Rossetti calls the poem ‘a cross between the antiphonal hymnal form and the ideas and phraseology of the Old Testament’. To the influence of the Old Testament, we should add the ideas and phraseology of Revelation. The wine-press of lines 62 and 78 (and likewise ‘that hour’ of line 81) refers to the wrath of God at the Last Judgement; cf. Revelation 14:19–20: ‘And the angel thrust in his sickle into the earth, and gathered the vine of the earth, and cast it into the great winepress of the wrath of God. And the winepress was trodden without the city, and blood came out of the winepress, even unto the horse bridles, by the space of a thousand and six hundred furlongs.’

The Anthologia Sacra appears to be Swinburne’s invention; his Greek means ‘the shining lights in heaven I shall hide from you, for one night you will have seven, etc.’ Metrically, the first line consists of an iamb and a bacchiac; the second line appears to be a variant of the first. The third line is iambic trimeter.

‘Skirts’ (line 4) are ‘the beginning or end of a period of time’ (OED 9b). ‘Thick darkness’ (line 36) is a recurrent phrase in the Old Testament. For ‘before’ and ‘behind’ (lines 37 and 38), cf. Psalms 139:5, ‘Thou hast beset me behind and before.’ ‘Remnant’ (line 39), according to the OED, can mean by allusion to Isaiah 10:22, ‘a small number of Jews that survives persecution, in whom future hope is vested’. ‘Put away’ (line 87) commonly means ‘divorce’ in the Bible. Line 127 derives from Ezekiel 34:16, ‘I… will bind up that which was broken.’

The poem consists of alternating trimeter and dimeter lines of both iambs and anapests. The stanza rhymes ababcdcd; note the double and triple rhymes ‘over thee’, ‘cover thee’ / ‘over us’, ‘cover us’; ‘love thee’, ‘above thee’ / ‘love us’, ‘above us’; ‘sunder thee’, ‘under thee’ / ‘sunder us’, ‘under us’; ‘reach me’, ‘beseech me’ / ‘reach thee’, ‘beseech thee’; ‘gold on you’, ‘hold on you’ / ‘gold on us’, ‘hold on us’. The antiphony is both semantic (as even-numbered antiphones recall the wording of the previous odd-numbered antiphones) and rhythmic (many of the rhyme-words are repeated in the pairs of antiphones, with one or two new rhymes introduced in the successor).

A Lamentation

The poem invokes the lamentation of Thetis (line 114) over her dead son Achilles, which Homer recounts in the Odyssey (at the beginning of Book 24), and also the dead Heracles (line 122), killed unintentionally by his wife Deianira; the chorus in Sophocles’s Women of Trachis laments both Heracles and Deianira. (Matthew Arnold’s ‘Fragment of a Chorus of a “Dejaneira” ’, though probably written much earlier, was published only in 1867.) Lamentations, one of the books of the Old Testament, is Jeremiah’s lament over the destruction of Jerusalem; the Lamentation, one of the lessons read during Holy Week, is taken from it.

The phrase ‘the desire of mine eyes’ (line 56) is related to the phrases ‘the desire of thine eyes’, ‘the desire of your eyes’, and ‘the desire of their eyes’, which all occur in Ezekiel 24 (and nowhere else in the Bible).

The metre and the rhyme scheme vary among the sections. The three stanzas of the first section are all trimeter lines of both iambs and anapests. Note the abcabc rhymes in the first stanza and the abcdabcd rhymes in the second. The second section consists of several stanzas. The first rhymes abaab and consists of tetrameters (iambo-anapestic); ‘travail’ (line 48) is stressed on the first syllable. The second stanza consists of alternating trimeter and dimeter lines, each consisting of both iambs and anapests. It is composed of nine quatrains with cross rhymes. The remaining stanzas of the section are made of tetrameter lines of both iambs and anapests rhyming abcabc. The third section consists of iambic trimeter lines in stanzas rhyming abcabcabc.

Anima Anceps

The title means literally ‘two-fold soul’. The source is a formula which Victor Hugo is likely to have invented, in Book 8, Chapter 6 of Notre-Dame de Paris (1831):

Alors levant la main sur l’égyptienne il s’écria d’une voix funèbre: «I nunc, anima anceps, et sit tibi Deus misericors!»

C’était la redoutable formule dont on avait coutume de clore ces sombres cérémonies. C’était le signal convenu du prêtre au bourreau.

[Then he raised his hand over the gypsy girl and pronounced sombrely: ‘Go therefore, divided soul, and may God be merciful to you.’ It was the awful formula by which it was customary to conclude these grim ceremonies. It was the appointed signal of the priest to the hangman.]

Parts of Arthur Clough’s Dipsychus (1865; the title means ‘double-minded’ or ‘double-souled’) were published in 1862 and 1863; Swinburne frequently quotes from the poem in his later letters, while maintaining reservations about Clough’s merits.

For the address to the soul, cf. Hadrian’s lines ‘Animula, vagula, blandula’, translated by Matthew Prior, Byron and others. For the rhyme ‘rafter’ and ‘laughter’ (lines 34 and 35), cf. Shelley’s ‘Lines (“When the lamp is shattered”)’ (1824), lines 29 and 31.

It is written in iambic dimeter; the rhyme scheme is aaabcccbdddbeeeb. All rhymes except for b are feminine.

In the Orchard

The poem is inspired by an anonymous Provençal alba, or dawn-song (a genre without a fixed metre or form in which a lover laments the imminent separation from the other lover at the break of day). It begins ‘En un vergier’ (‘In an orchard’) and consists of six stanzas of four lines each; the last line of each stanza is the refrain ‘Oy Dieus, oy Dieus, de l’abla!, tan tost ve’ (‘Ah God, ah God, the dawn! it comes so fast’). The text was available in editions like F. J. M. Raynouard’s Choix des poésies originales des troubadours (1821) and C. A. F. Mahn’s Gedichte der Troubadours (1856). A convenient modern edition is R. T. Hill and T. C. Bergin, Anthology of the Provençal Troubadours (2nd ed., 1973). For more information about the genre, see Eos: An Enquiry into the Theme of Lovers’ Meetings and Partings at Dawn in Poetry, ed. Arthur T. Hatto, 1965. Pound translated the alba as ‘Alba Innominata’ in 1910. By ‘Provençal burden’ Swinburne indicates that he is adopting the music or undersong of Provençal lyric, rather than offering a translation. ‘Burden’, in addition, refers to the refrain at the end of each stanza.

The OED gives no instance of ‘plenilune’ (line 23) between c. 1600 and Swinburne in 1878.

The poem is in iambic pentameter and rhymes aabab; the b rhyme (‘soon’ in the refrain) is constant throughout.

A Match

‘Closes’ (line 5) are enclosures. The reference in lines 35–6 is to dice and cards, respectively.

The metre is iambic trimeter, the rhyme scheme is abccabab. The a and c rhymes are feminine.

Swinburne writes several lyrics in iambic trimeter octaves: ‘A Match’, ‘Rococo’, ‘Before Dawn’, ‘The Garden of Proserpine’; cf. ‘Madonna Mia’. Katherine Williams (in her 1986 doctoral dissertation from CUNY, ‘Song New-Born’: Renaissance Forms in Swinburne’s Lyrics) adduces Keats’s poem beginning ‘In a drear nighted December’ (1829) and Shelley’s poem ‘The Indian Serenade’ (1824) as other examples of iambic trimeter octaves.

Faustine

Published in the Spectator, 31 May 1862.

In Notes on Poems and Reviews (Appendix 1) Swinburne explains that ‘the idea that gives [these verses] such life as they have is simple enough: the transmigration of a single soul, doomed as though by accident from the first to all evil and no good, through many ages and forms, but clad always in the same type of fleshly beauty. The chance which suggested to me this poem was one which may happen any day to any man – the sudden sight of a living face which recalled the well-known likeness of another dead for centuries: in this instance, the noble and faultless type of the elder Faustina, as seen in coin and bust.’ (According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the elder Faustina’s coiffure is depicted with a coronal of plaits on top; the younger Faustina’s with rippling side waves and a small bun at the nape of the neck.)

The elder Faustina is Annia Galeria Faustina, who married the future emperor Antoninus Pius. She was the aunt of Marcus Aurelius, whom her daughter, also named Annia Galeria Faustina, married. Ancient historians like Cassius Dio and the authors of the Historia Augusta established the reputation of both women for treachery and licentiousness. The latter work reports many amours of the younger Faustina (including an affair with her son-in-law, whom it says she may have poisoned). The discrepancy between the characters of Marcus Aurelius and his son was explained by postulating a liaison between Faustina and a gladiator; she is said to have preferred sailors and gladiators. Gibbon summarizes: ‘the grave simplicity of the philosopher was ill calculated to engage her wanton levity, or to fix that unbounded passion for variety, which often discovered personal merit in the meanest of mankind. The Cupid of the ancients was, in general, a very sensual deity; and the amours of an empress, as they exact on her side the plainest advances, are seldom susceptible of much sentimental delicacy’ (The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 4). Neither Gibbon nor Swinburne was aware of the fictitious nature of much of the Historia Augusta, which was revealed by Hermann Dessau in 1889. According to Dio, she died either of the gout or by suicide.

Satan won the contest with God over Faustina’s soul ‘this time’ (line 25); the contest over Job was the previous time. The combats of gladiators are described in lines 65–80; the words ‘morituri te salutant’ of the epigraph (in full, ‘Hail, empress Faustina, they who are about to die salute you’) are the traditional greeting of gladiators (see H. J. Leon, ‘Morituri Te Salutamus’, Transactions of the American Philological Association 70, 1939, pp. 46–50; cf. Jean Gérôme’s painting Ave Cœsar, Morituri Te Salutant exhibited in 1859). She is a Bacchanal (line 99), a votary of Bacchus and so a drunken reveller, but she is also a votary of Priapus, the ithyphallic god whose cult diffused from the region of Lampsacus (line 146), as well as a lesbian like Sappho of Mitylene (lines 117–24). Priapus ‘metes the gardens with his rod’ (line 147) because, as a garden god, his image was usually situated in the garden; cf. Catullus’s ‘Priapean’ poems (18, 19, and 20), usually regarded as spurious; Swinburne read Catullus with ‘delight and wonder’ at Eton (unpublished letter quoted in Rooksby, p. 30).

‘Dust and din’ (line 82) is a Victorian collocation: cf. Tennyson, In Memoriam (1850) LXXXIX.8, and Arnold, Empedocles on Etna (1852) Act 1, Scene 2, line 206. ‘Dashed with dew’ (line 103) recalls Tennyson’s ‘Dashed together in blinding dew’, from ‘A Vision of Sin’ (1842), line 42. ‘Serene’ (line 114), in reference to heavenly bodies, means ‘shining with a clear and tranquil light’ (OED, 1b). ‘Pulseless’ (line 115) can mean ‘unfeeling, pitiless’ as well as ‘devoid of life’.

The metre is iambic; ‘devil’ in line 19 ought to be scanned as a monosyllable. The four-line quatrains rhyme abab and alternate between tetrameter and dimeter lines. The last word of each quatrain is ‘Faustine’, for which Swinburne finds forty-one rhymes.

A Cameo

A description of a cameo, with the allegorical figures of Desire, Pain, Pleasure, Satiety, Hate and Death, as well as a crowd of senses, sorrows, sins and strange loves. Strictly speaking, cameos are not painted (line 2). For the title, compare Gautier’s Émaux et Camées (1852) and his intention that ‘chaque pièce [of that collection] devait être un médaillon’. For contemporary sonnets on works of art, recall Rossetti’s ‘Sonnets for Pictures’, published in 1850. For the topic of ekphrasis in general, see John Hollander’s The Gazer’s Spirit (1995).

‘Pash’ (line 8), to smash violently, may be influenced by the intransitive use of the word ‘said of the dashing action of sudden heavy rain… and of the action of beating or striking water as by the feet of the horse’ (OED).

The sonnet is of the Italian sort; it rhymes abba abba cde cde.

Song Before Death

The poem is a translation from a song in Letter 68 of Sade’s Aline et Valcour, his philosophical epistolary novel published in 1795:

Air: Romance de Nina.

Mère adorée, en un moment

La mort t’enlève à ma tendresse!

Toi qui survis, ô mon amant!

Reviens consoler ta maîtresse.

Ah! qu’il revienne (bis), hélas! hélas!

Mais le bien-aimé ne vient pas.

Comme la rose au doux printemps

S’entrouvre au souffle du zéphyre,

Mon âme à ces tendres accents

S’ouvrirait de même au délire.

En vain, j’écoute: hélas! hélas!

Le bien-aimé ne parle pas.

Vous qui viendrez verser des pleurs

Sur ce cercueil où je repose,

En gémissant sur mes douleurs,

Dites a l’amant qui les cause

Qu’il fut sans cesse, hélas! hélas!

Le bien-aimé jusqu’au trépas.

In a letter of 1862 (Lang, 1, 58), Swinburne describes the song as ‘about the most exquisite piece of simple finished language and musical effect in all 18th century French literature’. On Swinburne’s initial reading of Sade, see Rooksby, pp. 75–7. For his abiding interest, consult the index to the letters.

The title and the date ‘1795’ indicate that the speaker is anticipating execution during the French Revolution.

Swinburne translates into iambic tetrameter lines in stanzas that rhyme ababcc.

Wise reproduces the manuscript of the poem in the 1919 Bibliography (p. 110).

Rococo

In the nineteenth century the term could mean merely ‘old-fashioned’, and even when applied to French decoration, it did not specifically refer to the florid, light style conceived in reaction to the official baroque of Louis XIV. The OED’s first citation for ‘rococo’ is dated 1836. Swinburne invokes Juliette (line 62), whose name recalls the depraved heroine of Sade’s novel, published in 1797.

On the newly recovered fashion for the rococo in French culture in the nineteenth century, see the chapter ‘Age of Rococo’ in Maxine G. Cutler’s Evocations of the Eighteenth Century in French Poetry, 1800–1869 (1970). Gautier was central in the new appreciation for it; see his poems ‘Rocaille’, ‘Pastel’ (originally called ‘Roccoco’), ‘Watteau’, etc. Banville and Hugo (‘La Fête chez Thérèse’) were also important in its recovery, as were Baudelaire and the Goncourt brothers.

‘Sanguine’ (line 8) means ‘of blood-red colour’, but the sense ‘bloodthirsty, delighting in bloodshed’ is not absent. Both meanings were literary uses of the word when Swinburne wrote the poem.

The poem is written in iambic trimeter; the stanzas rhyme ababcdcd, where a and c have feminine endings. The last two rhymes of each stanza alternate between ‘pleasure/pain’ and ‘remember/forget’. On iambic trimeter octaves, see the note to ‘A Match’.

Wise reproduces a manuscript of the poem in the 1919 Bibliography (p. 113).

Stage Love

Bacon, in his essay on love, offers one of the classical contrasts between stage love and love in life: ‘The stage is more beholding to love, than the life of man. For as to the stage, love is ever matter of comedies, and now and then of tragedies; but in life it doth much mischief: sometimes like a siren; sometimes like a fury.’

The poem is written in trochaics with six stresses (the last unstressed syllable is sometimes omitted, as often in trochaic verse); the stanzas rhyme aabb, where b is feminine. Trochaics are among the most enduring metres of classical poetry: Archilochus wrote in trochaics, the metre occurred regularly in Greek and Latin tragedy and comedy and also in late works like the Pervigilium Veneris, and it was used in goliardic verse. In English, by the eighteenth century, the trochaic had typically been used for lighter purposes. William Blake’s songs in trochees, like ‘The Tyger’, introduced a new weight and flexibility to the metre. Tennyson’s ‘Locksley Hall’ (1842), Longfellow’s ‘The Song of Hiawatha’ (1855), and Browning’s ‘A Toccata of Galuppi’s’ (1855) were recent poems in trochaics.

Wise prints a manuscript of the poem in his 1919 Bibliography (p. 113) and in A Swinburne Library, facing page 25.

The Leper

Swinburne invents a French source for the story, which he offers in a note at the end: ‘At that time there was in this land a great number of lepers, which greatly displeased the king, seeing that because of them the Lord must have been grievously wroth. Now it happened that a noble lady named Yolande de Sallières was afflicted and utterly ravaged by this base sickness; all her friends and relatives, with the fear of the Lord before their eyes, made her quit their houses and would never receive or help a thing cursed of God, stinking and abominable to all men. This lady had been very beautiful and graceful of figure; she was generous of body and lascivious in her life. However, none of the lovers who had often embraced and kissed her very tenderly would shelter any longer such an ugly woman and such a detestable sinner. One clerk alone who had been at first her servant and her intermediary in the matter of love took her in, hiding her in a small hut. There the villainous woman died of great misery and an evil death: and after her, the aforesaid clerk died, who had of his great love for six months tended, washed, dressed and undressed her with his own hands every day. They even say that this wicked man and cursed clerk, calling to mind the great beauty of this woman, now gone by and ravaged, delighted many times to kiss her on her foul, leprous mouth and to embrace her gently with loving hands. Thus, he died of the same abominable malady. This happened near Fontainebellant in Gastinois. And when King Philip heard this story, he was greatly astonished.’

Clyde K. Hyder (‘The Medieval Background of Swinburne’s The Leper’, PMLA 46, December 1931, pp. 1280–8) identifies a source behind various details of Swinburne’s archaic French; he also notes correspondences between the poem and the medieval poem Amis and Amiloun, which Swinburne read in Henry Weber’s Metrical Romances (1810).

William Empson discusses the word ‘delicate’ (line 3) in The Structure of Complex Words (1951, p. 78), where he writes that in this poem ‘the sadism is adequately absorbed or dramatised into a story where both characters are humane, and indeed behave better than they think; Swinburne nowhere else (that I have read him) succeeds in imagining two people.’

The metre is iambic tetrameter; the stanza is a quatrain rhyming abab.

An early version of the poem, entitled ‘A Vigil’, was transcribed by T. J. Wise in A Swinburne Library (p. 2) and by Lafourcade (Vol. 2, pp. 63–4 and 573). Cecil Lang warns that the transcriptions are inaccurate (The Pre-Raphaelites and their Circle, 1975, p. 521). There is a reproduction of the first four stanzas of ‘A Vigil’ in T. Earle Welby’s A Study of Swinburne (1976), p. 60.

A Ballad of Burdens

‘Ballad’ indicates that the poem is a ballade, the form of which was standardized by Guillaume de Machaut and Eustache Deschamps in the fourteenth century: three stanzas of either eight octosyllabic lines or ten decasyllabic lines; usually with an envoy at the end; having a refrain or rebriche as the last line of each stanza and of the envoy; and maintaining the same rhymes for each stanza. The greatest ballades were written by Villon in the fifteenth century and by Charles d’Orléans in the sixteenth. Despite efforts by Chaucer and Gower, the form was never naturalized in English; in France it fell into disuse in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Gautier’s essay on Villon in Les Grotesques (1844) was influential in establishing Villon’s reputation in the nineteenth century. (Although Banville was composing ballades ‘after the manner of Villon’ at the same time as Swinburne, they were not published until 1873; his polemical Petit traité de poésie française, insisting on the necessity of returning to forms like the rondeau, triolet, and ballade, appeared in 1872.) Swinburne’s enthusiasm for the fifteenth-century French poet was longstanding; in the early 1860s, he and Rossetti planned to translate all of Villon’s work. His translation from this period entitled ‘The Ballad of Villon and Fat Madge’, like ‘A Ballad of Burdens’, does not preserve the same rhymes in each stanza; in contrast, his translations of Villon’s ballades published in Poems and Ballads, Second Series (1878) adhere to the stricter rhyme scheme. ‘A Ballad of Burdens’ is a triple ballade; the stanza rhymes ababbcbc, and c is constant in each stanza.

‘Burden’, besides meaning ‘refrain’ and ‘accompanying song’, is used in the English Bible (like onus in the Vulgate) to render Hebrew massa, which was generally taken in English to mean a ‘burdensome or heavy lot or fate’. See Isaiah 13:1 and OED, ‘burden’ 8. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s ‘The Burden of Nineveh’, as printed in 1856, added below the title ‘ “Burden. Heavy calamity; the chorus of a song.” – Dictionary.’

For ‘the burden of fair women’ (line 1), cf. Tennyson’s title, ‘A Dream of Fair Women’ (1832). Compare the repeated line ‘I would that I were dead’ of Tennyson’s ‘Mariana’ (1830) with line 28.

Rondel

See note to the first rondel (p. 337), and recall that the form of the rondeau was very fluid before the time of Marot. The poem is in two stanzas, like Villon’s rondeau on death, which Rossetti translated in 1869. The metre is iambic pentameter, the rhyme scheme is aabbcc (c is the same rhyme in both stanzas), the rentrement is iambic dimeter.

‘White death’ (line 11) occurs twice in Shelley, in Prometheus Unbound (1820) Act 4, line 424 and Adonais (1821), line 66. It is most likely an equivalent to the more common poetic phrase ‘pale death’.

Wise prints a manuscript of the poem in his 1919 Bibliography (p. 109) and in A Swinburne Library, facing page 24.

Before the Mirror

The poem was written for Whistler’s The Little White Girl: Symphony in White no. 2 (1864), now in the Tate Gallery, the second of the series Whistler only later called ‘symphonies in white’. (Whistler may have taken his synaesthetic title from Gautier’s ‘Symphonie en blanc majeur’, or perhaps from a critic’s description of The White Girl: Symphony in White, no. 1, 1862.) A girl in white leans on a white mantelpiece, extending one arm along it, holds a fan in the hand of her other arm, and looks at a Japanese vase at the end of the mantelpiece. Her head is inclined to the mirror above the mantel; her reflection is sadder than her face. Swinburne wrote to Whistler in 1865 (Lang, 1, 118–20): ‘I know [the idea of the poem] was entirely and only suggested to me by the picture, where I found at once the metaphor of the rose and the notion of sad and glad mystery in the face languidly contemplative of its own phantom and all other things seen by their phantoms.’ Whistler liked the verses; the fourth and sixth stanzas were printed in the Royal Academy catalogue of 1865; and he had the poem printed on gold paper and fastened to the frame (Frederick A. Sweet, James McNeill Whistler, 1968, p. 57). John Hollander (The Gazer’s Spirit, 1995) suggests that this last fact may account for the poem’s subtitle. See also Linda Merrill, The Peacock Room: A Cultural Biography (1998), pp. 62–6, 357.

‘Behind the veil’ (line 8) recalls Tennyson’s In Memoriam (1850) LVI, 28 (‘Behind the veil, behind the veil’), as well as the metaphysical veils of Coleridge and Shelley, and also Hebrews 6:19.

The poem is iambic; the length of the lines varies. The rhyme scheme is a3b2a3b2c3c3b5. Note that there is an internal c rhyme after the third foot in the last line of each stanza. Hollander remarks on the third section of the poem: ‘The poem now moves inside the girl’s reveries to the traces of the past that must inevitably emerge from its depths, even as – in Swinburne’s verse throughout this poem – the internal rhymes emerge in the ultimate line of each stanza.’

Erotion

Swinburne explained that he wrote this poem as a comment on Simeon Solomon’s painting Damon and Aglae:

a picture of two young lovers in fresh fullness of first love crossed and troubled visibly by the mere shadow and the mere breath of doubt, the dream of inevitable change to come which dims the longing eyes of the girl with a ghostly foreknowledge that this too shall pass away, as with arms half clinging and half repellent she seems at once to hold off and to hold fast the lover whose bright youth for the moment is smiling back in the face of hers – a face full of the soft fear and secret certitude of future things which I have tried elsewhere to render in the verse called ‘Erotion’ written as a comment on this picture, with design to express the subtle passionate sense of mortality in love itself which wells up from ‘the middle spring of pleasure’, yet cannot quite kill the day’s delight or eat away with the bitter poison of doubt the burning faith and self-abandoned fondness of the hour; since, at least, though the future be for others, and the love now here turn elsewhere to seek pasture in fresh fields from other flowers, the vows and kisses of these present lips are not theirs but hers, as the memory of his love and the shadow of his youth shall be hers for ever.

(Swinburne, ‘Simeon Solomon: Notes on His “Vision of Love” and Other Studies’, The Dark Blue, July 1871, p. 574)

The first eight lines of Swinburne’s poem were printed in the 1866 exhibition catalogue of the Royal Academy of Arts under the entry for Damon and Aglae. The painting was sold at Sotheby’s in 1978.

‘Erotion’ is a Greek name, a diminutive of ‘Eros’. Although here and in ‘Anactoria’ the name is presumably applied to a man, in Martial, for example, it is applied to a young slave girl (5.34, 5.37, 10.61).

Swinburne ended his close association and friendship with Solomon after Solomon was arrested in 1873 for soliciting outside a public lavatory.

The poem is in heroic couplets. Complete sentences fit into either couplets or quatrains. There is little enjambment.

A facsimile of a manuscript of the poem is provided in Harry B. Smith’s A Sentimental Library (1914), facing p. 202.

In Memory of Walter Savage Landor

Swinburne’s veneration of Landor began in his Eton days (Rooksby, p. 30). He admired Landor’s classicism and republicanism. They met in Florence (‘flower-town’, line 1) in March 1864. Landor accepted the dedication of Atalanta in Calydon but died before it could reach him in print. In the article he contributed to the ninth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1882), Swinburne praised Landor’s ideal of civic and heroic life, his ‘passionate compassion, his bitter and burning pity for all wrongs endured in all the world’, and his loyalty and liberality; and he particularly admired his Hellenics (1847) and Imaginary Conversations of Greeks and Romans (1853).

Landor was eighty-nine years old when they met, and Swinburne was about to turn twenty-seven (line 23). The address ‘Look earthward now’ (line 34) recalls Milton’s ‘Lycidas’, line 163, ‘Look homeward Angel now’, and it may also be influenced by Christina Rossetti, ‘Your eyes look earthward’, in ‘The Convent Threshold’ (1862), line 17. ‘Dedicated’ (line 47) means ‘consecrated’.

The poem is written in quatrains consisting of alternate iambic tetrameter and iambic dimeter lines; they rhyme abab.

A Song in Time of Order. 1852 and A Song in Time of Revolution. 1860

‘A Song in Time of Order. 1852’ was published in the Spectator, 26 April 1862, and ‘A Song in Time of Revolution. 1860’ in the Spectator, 28 June 1862.

Both poems are expressions of Swinburne’s republican convictions. The date appended to the title of the first poem indicates that his target is Louis Napoleon, who became emperor of France in 1852. He had been elected president of France in 1848, backed by the newly founded ‘Party of Order’; ‘order’ was one of his political slogans. In 1851, when his term as president expired, he staged a successful coup d’état; the next year he began to deport his enemies to Algeria and French Guiana; later that year, he was proclaimed emperor. He also sent convicts with long sentences to French Guiana; Cayenne (line 50) became known as the ‘city of the condemned’. See Hugo’s ‘Hymne des Transportés’ (1853). Austria (line 50) dominated the disunited Italian states (until 1859). Louis Napoleon’s parentage had been a topic of contemporary gossip (line 39, ‘Buonaparte the bastard’). The revolution that Swinburne praises in the second poem is Garibaldi’s successful offensive into Italy: capturing first Sicily and then Naples in 1860, he handed both over to Victor Emmanuel and greeted him as the king of a united Italy.

Contrast the title with the occasional prayers of the Book of Common Prayer, for example, ‘In the Time of War and Tumults’. Lines 29–30 of the first poem and lines 19–20 of the second are reminiscent of God’s power in Job; see, for example, Job 38:8 and 41:1. See, too, Hugo’s ‘Lux’ (1853) line 202–6. ‘Reins’ (line 27, ‘A Song in Time of Revolution’) means ‘loins’.

For Swinburne, Victor Hugo’s collection of poems denouncing Louis Napoleon, Les Châtiments (1853), was a crucial example of republicanism in poetry. (Much of Swinburne’s critical work on Hugo, including comments on Les Châtiments, is reprinted in the Bonchurch edition of his works, volume 13. However, that volume includes works now known not to have been written by Swinburne, and it is misleading in other respects, too; see Clyde Hyder, Swinburne as Critic, 1972.) Lafourcade points to the influence of Hugo’s ‘Ultima Verba’ in particular. Consider Hugo’s last stanza in relation to the lines ‘While three men hold together, The kingdoms are less by three’ (‘A Song in Time of Order’):

Si l’on n’est plus que mille, eh bien, j’en suis! Si même

Ils ne sont plus que cent, je brave encor Sylla;

S’il en demeure dix, je serai le dixième;

Et s’il n’en reste qu’un, je serai celui-là!

(Sylla, or Sulla, the Roman tyrant, is one of Hugo’s names for Louis Napoleon.)

‘A Song in Time of Order’ is in quatrains of trimeter lines that combine iambs and anapests; ‘gunwale’ (line 12) is pronounced as a strong trochee, not as a spondee. The quatrains rhyme abab. ‘A Song in Time of Revolution’ is in hexameter rhyming couplets, combining anapests and iambs; there is a rhyme after the third foot as well as at the end of the line.

To Victor Hugo

Throughout his life Swinburne was passionately enthusiastic about Victor Hugo. In this poem, he recalls Hugo’s childhood during the Napoleonic period and pays tribute to Hugo’s self-enforced, principled exile (forced into exile after he resisted Louis Napoleon’s coup d’état, he refused to enter France after the general amnesty of 1859). In his prose works of 1852, Napoléon le Petit and Histoire d’un crime, he indicted Napoleon III, and in 1853 he wrote a book of satirical poems condemning him, Les Châtiments. Swinburne praises the principles of the French Revolution (line 99) and the democratic uprisings of 1848, while lamenting their apparent political failure. He contrasts the political pessimism of his generation (lines 124-6) with Hugo’s optimism (line 153). The tenth stanza recalls the exile of Swinburne’s ancestors during the English Civil War. The eighteenth stanza invokes Prometheus.

Contrast the opening two lines with Tennyson, ‘Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington’ (1852), line 266: ‘On God and Godlike men we build our trust.’ ‘Uplift’ in lines 50 and 128 is an older form of ‘uplifted’; it survived in nineteenth-century poetry. Compare line 99 with Genesis 1:3, ‘And God said, Let there be light; and there was light.’ Swinburne refers to ‘the vast and various universe created by the fiat lux of Victor Hugo’ (Studies in Prose and Poetry, [1889] 1894, p. 277). Line 166 recalls Shakespeare’s Macbeth, ‘I gin to be a-weary of the sun’ (Act V, Scene 5, line 49).

Swinburne sent a copy of Poems and Ballads to Hugo, who could not read English but who asked a friend to translate this poem. He wrote graciously to Swinburne about ‘les nobles et magnifiques strophes que vous m’adressez’ (Lang, 1, 248n2).

The poem is written in iambics; the eight-line stanza consists of two trimeter lines, a pentameter, two trimeters, a pentameter, a tetrameter, and a pentameter; rhyming aabccbdd. The stanza is very like that of Milton’s hymn in ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’, except that Milton’s last line is a hexameter.

Before Dawn

The metre is iambic trimeter. The stanza rhymes aaabcccb, where a and c have feminine endings. On rhyming triplets, see Swinburne’s discussion of Robert Herrick (1891; reprinted in Studies in Prose and Poetry, 1894). With ‘no abiding’ (line 71), compare 1 Chronicles 29:15, ‘our days on the earth are as a shadow, and there is none abiding’.

Dolores

Dolores is Swinburne’s anti-madonna; her name derives from the phrase ‘Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows’ (which, in French, is Swinburne’s sub-title). ‘Our Lady of Pain’, Swinburne’s pagan darker Venus, is his answer to the Christian ‘Our Lady of Sorrows’, although his paganism is tinged with his own interest in sadomasochism (see Lang, 1, 123). Words and phrases from the Bible (lines 10 and 439: Matthew 18:21–2; line 137: Matthew 9:17 and elsewhere; lines 371–2: Exodus 7:9–12; line 328: Matthew 13:24–40), the Loreto Litany of the Blessed Virgin (line 19 and ‘tower of ivory’; line 21 and ‘mystical rose’; line 22 and ‘house of gold’), the prayers of the Mass (e.g. lines 133–4 and the taking of communion), the ‘Ave Maria’ (line 39 and ‘blessed among women’), and the Lord’s Prayer (lines 279 and 391) are blasphemously deployed. Baudelaire’s poems ‘À une Madonne’ and ‘Les Litanies de Satan’ (1857) are models for Swinburne; he writes admiringly about these two poems in particular in his 1862 Spectator review of Les Fleurs du Mal.

Libitina (lines 51, 423) is the Roman goddess of burials, misidentified since antiquity with Venus; Priapus (lines 51, 423) is the ithyphallic god of gardens (lines 303, 313), whose cult was centred in Lampsacus (line 405). The prayer to Dolores to intercede with her father Priapus on our behalf (line 311) is a parody of Catholic prayer. Priapus is the subject of three poems once attributed to Catullus (line 340); Swinburne quotes two lines of one of these in a note to line 307: ‘for in its cities the coast of the Hellespont, more oysterous than most, honours you particularly’. One of his lyrics (Carmina 32) is addressed to the girl Ipsitilla (cf. Swinburne’s line 326).

Swinburne reverses the usual associations of cypress and myrtle in lines 175–6. The Thalassian in line 223 is Aphrodite Anadyomene, risen again in Roman cruelty. The gladiatorial combats follow in the next stanzas, for which Lafourcade adduces the preface to Gautier’s Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835) as an influence. Nero is introduced in lines 249–56 (see Linda Dowling, ‘Nero and the Aesthetics of Torture’, The Victorian Newsletter, Fall 1984, pp. 2–5, on the aestheticized Nero in the nineteenth century). Alciphron and Arisbe (line 299) are names that occur in Greek history and mythology, but Swinburne is most likely using them simply as the names of a male and a female lover.

The stanzas beginning at line 329 describe Cybele, the ‘Great Mother of the Gods’, whose worship, characterized by ecstatic states and insensibility to pain, arose in Phrygia (line 330), where her main cult was located on Mount Dindymus (line 345). It later spread to Greece and Rome, where one of her Latin names was the ‘Idaean Mother’ (line 333). Her priests castrated themselves as Cybele’s lover, Attis, did; Catullus, Carmina 63, relates that legend (line 340). In ‘Notes on Poems and Reviews’ (Appendix 1), Swinburne contrasts Dolores, ‘the darker Venus’, with both the Virgin Mary and Cybele.

Cotys or Cotyto (line 409, Cotytto) was a Thracian goddess later worshipped orgiastically in Corinth and Sicily as well as in Thrace. Astarte (in Greek) or Ashtaroth (in the Bible) are names for Ishtar, the Mesopotamian goddess of love and war. Privately, Swinburne associates the ‘Europian Cotytto’ and the ‘Asiatic Aphrodite of Aphaca’ (Lang, 1, 406) with Sade and with sadomasochistic indulgence (see Lang, 1, 312).

‘Seventy times seven’ (lines 10 and 439) recalls Matthew 18:22. J. C. Maxwell (Notes and Queries, Vol. 21, January 1974, p. 15) offers a parallel to and possible source of line 159 in Thackeray’s The Newcomes (1855), Chapter 65, ‘before marriages and cares and divisions had separated us’. Perhaps ‘live torches’ (line 245) refer to humans burnt alive; however, the OED offers no example of such a usage. A ‘visible God’ (line 320) echoes Timon of Athens, Act 4, Scene 3. The rod in lines 371–2 recalls Aaron’s rod in Exodus 7. Line 379 may invoke Sade, and line 380 alludes to the allegory of sin and death in Paradise Lost, Book 2; the OED records an obsolete usage of ‘incestuous’ meaning ‘begotten of incest’. The tares and grain of line 438 recall Christ’s parable in Matthew 13.