CHAPTER 8

In the Eye of a “Time of Troubles”: Terror in Russia, 1917–21

IN 1917 the overexertions of a protracted and failing war gravely unsettled Russia: the imperial army was on the verge of disintegration; famine stalked the major cities; the economy and exchequer were wasted; and industry was paralyzed. Twice before, in the time of the Crimean War and Russo-Japanese War, military defeat had shaken the tsarist regime and called forth prophylactic reforms. But in scale and intensity these earlier upheavals were nothing like the deep crisis brought on and fueled by the inordinate material and human sacrifices of the Very Great War. In February–March 1917, between the fall of the Peter-Paul Fortress and the resignation of Tsar Nicholas II, the forces of law and order crumbled, giving the signal for peasants to seize the land from their overlords and for minority nationalists along the periphery to press for autonomy or independence. This rising peasant and nationality disaffection was both cause and effect of a general dislocation which between 1917 and 1921 spiraled into an altogether peculiar and extreme “time of troubles” fraught with Furies.1

The contrast between France in 1789 and Russia in 1917 could not be more striking. When the Bastille fell, the Bourbon monarchy was at peace with Europe. Despite a momentary budgetary squeeze, its public finances and economy were sound, and so was its state apparatus, including the armed forces. Not surprisingly, the French Revolution heated up only gradually: it took between three and four years for France to go to war, for Louis XVI to be tried and executed, for civil war to erupt in the Vendée, and for terror to be put à l’ordre du jour.

Russia in War and Revolution, 1914 to 1921

In Russia the pace was altogether quicker. The Romanov empire was at war at the time of the uprising in February 1917 in Petrograd, and both civil war and foreign intervention broke forth within less than a year. Nicholas II was executed in mid-July 1918, and mass terror was decreed in early September. In the meantime, earlier that same year, aided and abetted by the Central Powers, Ukraine and several other non-Russian “borderlands” seceded. But above all, the fact of war was omnipresent from the creation, and became an urgent defining issue and force. Whereas the provisional governments of Lvov and Kerensky used the continuation of war as a stratagem to tame the revolution, the Bolsheviks envisioned a rush to peace to revolutionize it. Especially the moderates, notably the Kadets and Mensheviks, looked to the appeals of nationalism, the flow of Allied financial and military aid, and the discipline of the barracks to help restore a minimum of order and to consolidate a revolution from above, on the model of 1905. The spectacular failure and human cost of Kerensky’s military offensive in June 1917 discredited this political strategy. Presently the unreconstructed army was devitalized by the massive desertion of peasant-soldiers bent on joining the fast-spreading jacquerie against the nearest squire in the countryside instead of fighting the distant foreign enemy in pursuit of a chimeric “peace without annexations and indemnities.”

This irreversible military predicament encouraged Lenin to intensify his drive for immediate “peace, bread, and land.” In turn, Kerensky ordered General Kornilov, the new commander-in-chief, to reestablish discipline so that the army would be fit to continue fighting the war abroad and enforce order at home. But convinced that time was running out, and distrustful of non-autocratic government, in late August Kornilov launched an armed insurrection to establish a military dictatorship to be backed by the old ruling and governing classes. With no “national guard” of its own to protect it, the provisional government summoned supporters, including the hated Bolsheviks, to take to the streets so as to parry this diehard defiance. Apart from benefiting the Bolsheviks and their sympathizers, Kornilov’s abortive coup further hastened the disintegration of the army, the rebellion of the peasantry, and the restlessness of the industrial proletariat.

Clearly, the inception and early infancy of the Russian Revolution, unlike that of the French Revolution, was marked by the political, economic, and social fallout of an exhausting and unsuccessful war effort. Russia’s general crisis in city and country was not the doing of the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, even if their militants exploited it. The ease with which Lenin’s inexperienced Red Guards invested the Winter Palace in October–November 1917 was less a measure of the Bolsheviks’ strength and perspicacity than of the provisional government’s irresolution and impotence in the face of snowballing domestic and foreign problems. To be sure, of all the political parties—which were, in any case, a fragile foreign implant in Russia’s autocratic political culture—the Bolshevik party was by far the best organized and disciplined, as well as the most adaptable. Even so, its accession to power was a perverse effect of the rampant destabilization of Europe’s largest and most populous, even if least developed, country, compounded by the dislocation of the concert of powers and the hyperbolic war in which it was trapped. While the Bolsheviks, like the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, were mentally and theoretically prepared for a conjuncture analogous to 1904–5, they did not anticipate—nor, for that matter, welcome—the colossal implosion which unhinged Russia starting in 1917. Although their decisions and actions were informed by their ideological and programmatic canon, this canon was, in turn, modified in the heat of emergent events which called forth unforeseen intentions, policies, and consequences.

Admittedly, the way the Bolsheviks took power was consistent with their credo of direct and defiant action, and their authoritarian rule following Red October was bound to provoke resistances which they were, of course, determined to counter and repress. But again, just as they were unprepared for the enormity of the crisis, so they were caught unawares by its Furies, which they were not alone to quicken. With the cave-in of sovereignty, it was relatively easy for the Bolsheviks to take the remnant residue of power into their own hands. It was altogether harder, however, to exercise and enforce this vestige of authority; to do so meant fending off a broad range of foes in an incipient civil war that was inseparable from an unbearable foreign war. It may well be that by virtue of its eventual costs and cruelties, this resolve to fight a civil war became the original sin or primal curse of Bolshevik governance during the birth throes of the Russian Revolution. Even in circumstances less wretched than those of 1917 to 1921 in Russia, war and civil war, separately or jointly, are the great scourge of limited or democratic government.

With the overall situation favorable to the intensification of chaos and the attendant friend-enemy dissociation, the Bolsheviks ventured upon a civil war freighted with the founding violence of a new Russia. Eventually this unforeseen internal war, exacerbated by the intervention of hostile foreign powers, became the formative experience of the Bolshevik leaders. This struggle, at once defiant and perilous, fostered their theoretical and mental predisposition, rooted in Russia’s authoritarian past, to centralize power, govern by ukase, resort to violence, control the economy, and impose ideological uniformity. At the same time they incited revolutionary zeal and embraced extreme voluntarism. The Bolshevik project was an inconstant amalgam of ideology and circumstance, of intention and improvisation, of necessity and choice, of fate and chance. Perhaps without the guiding historical example of the French Jacobins, which was ubiquitous, the Bolsheviks would have either hesitated to bid for undivided power or flinched once they realized that they faced an even more forbidding situation than their predecessors of the late eighteenth century. But then again, the brazen daring of the Bolsheviks, like that of the Jacobins before them, kept being vindicated by altogether improbable successes which legitimated and strengthened their tenuous and beleaguered regime.

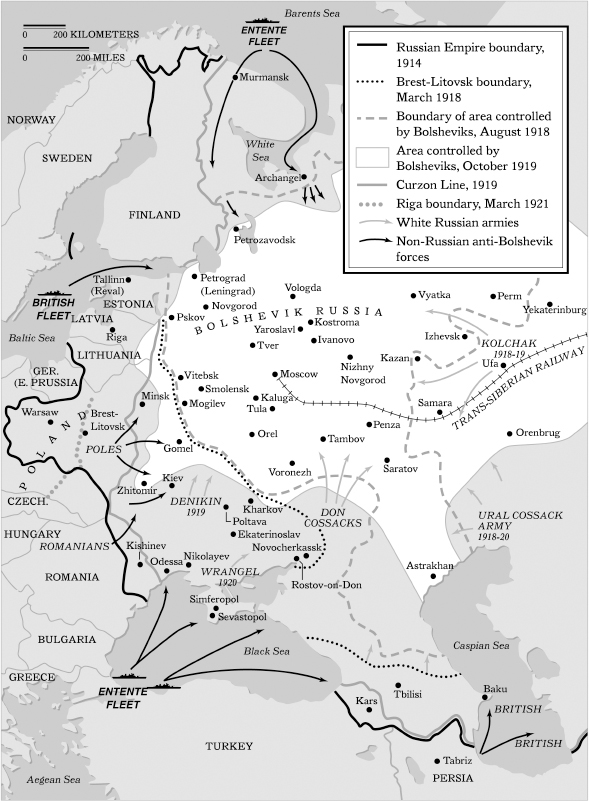

Civil war was of much greater importance in the Russian than the French Revolution. Although the main civil war theaters were in the south and southeast, there was fighting in other regions as well. The Bolsheviks fought, above all, the White generals, who embodied the counterrevolution. Of course, they also did battle with the Kadets, the Mensheviks, and the Socialist Revolutionaries, as well as with several of the minority nationalities. In addition, they fought rebellious peasants in Ukraine, in Tambov province, and in the lands of the Volga. Ultimately, however, the struggle between the Bolsheviks and the White Guards was the crucial one, all the other conflicts being of subordinate importance. Given this primacy of absolute enmity between Reds and Whites, the peremptory dismissal of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918 was of marginal consequence: while it widened the fatal split between the Bolsheviks and the bulk of the Socialist Revolutionaries, it left Kolchak, Denikin, and Iudenich, the White generals, altogether indifferent. Bent on restoring the old regime and empire, even if stripped of the Romanov dynasty, the latter were as hostile to liberal or socialist democracy as they were to proletarian dictatorship.

Actually, Kornilov’s stillborn military defiance of Kerensky’s government in late August 1917 presaged the counterrevolution in the Russian Revolution. Even though their troops kept deserting them, all ex-tsarist senior officers stayed home to organize resistance rather than go into exile, as so many of their French counterparts had done in 1789. Almost immediately following the Bolshevik takeover in Petrograd, they made their way to the Don territories, with the idea of organizing White Guards of assorted volunteers and seasoned Cossacks to reclaim their world of yesterday. In any case, when, on November 3, 1917, Lenin proclaimed the start of civil war, he and his associates knew that they would have to engage not only the Kadets, but also, and above all, the implacable imperial officers corps.

The French Revolution was constantly present at the creation of the Russian Revolution.2 Many of the actors in the Russian Revolution modeled themselves after those in the French Revolution: for the Kadets, the Feuillants were the worthy prototype; for the Mensheviks, the Girondins; for the Bolsheviks, the Jacobins. Some “consciously” used the French Revolution “as a pattern or guide for action”; others did so “unconsciously,” on the basis of their “implicit or virtual” experience of it. Indeed, the French Revolution served as a road map for some, a model for others, and an incubus for still others. Unlike the Jacobins, who had looked back to ancient Rome for inspiration and guidance, as well as a legitimating pedigree, the Bolsheviks sought their historical referents in a more recent past. Indeed, they became fervent analogists, constantly weighing the resemblances and differences between themselves and the Jacobins. In making these comparisons they drew on the politically informed debates about the French Revolution within the Russian left during the decades before 1917.

The question of violence was central to this critical engagement with the paradigmatic Great Revolution, all the more so because of the repressive violence in its aftershocks in 1848 and 1871. Not only Marx and Engels theorized the role of violence in the unfolding Socialist project, but so did the action intellectuals of the Socialist movements of Central Europe and Russia. Indeed, unlike during the prelude to the French Revolution, violence became an ever more urgent issue during the pre-revolution of the Russian Revolution. In 1905 the tsarist government had not hesitated to crush the rebels and soviets of St. Petersburg and Moscow, and between 1907 and 1917 it had used bold physical and rhetorical violence to curb the reforms introduced with the October Manifesto. Many of the revolutionary leaders of 1917–18 were personally caught up in this repression, so that unlike their Jacobin forerunners, they experienced the state’s repressive force at first hand. Indeed, ever so many leading members of the Sixth Congress of the Bolshevik Party, meeting in July 1917, and all fifteen members of the first Council of People’s Commissars had spent years in prison, in Siberia, and in exile. Five of the latter had also been jailed by Kerensky’s Provisional Government.3

The would-be revolutionaries of 1917, compared to those of 1789, were conditioned, not to say hardened, for the exercise of violence. They came upon the political scene steeped in the theory, ideology, and history of its practice. The unprecedented slaughter of the Very Great War merely reinforced them in their conceptual and existential engagement with naked violence, especially since they considered Europe’s governors to have unleashed this monstrous conflict as a diversion to unnerve and divide the rising and restive forces of reform and revolution. Besides, of late, throughout Europe, including Russia, the reason of violence had become at least as central to the idées-forces of the far right as the far left.

Be that as it may, in the quagmire of 1917–18 there was no governing without recourse to violence. Abroad Russia faced a catastrophic situation, compounded by centrifugal pulls in its non-Russian peripheries, while at home polity, economy, judiciary, police, and army were in headlong decomposition. This external predicament and internal entropy reinforced each other, and the result was an exceptionally grave “time of troubles.” These troubles would be all the more furious, and consequently harder to curb, because of the peculiar features of Russia’s human geography. Most strikingly, Russia’s size was staggering: forty times the land area of France, with eleven time zones. In early 1918, cornered by the Central Powers, at Brest-Litovsk the Bolsheviks were able to cede territories one and a half times the size of Germany without crippling the nascent Socialist Federated Soviet Republic. Even in normal times, let alone in a time of troubles, Russia defied governance as a single unit—a single sovereignty—by virtue not only of its sheer expanse but also its bewildering diversity of cultures, its uneven levels of development, its primitive state of transport, and its encumbrance by a torpid peasant world. This rich but refractory endowment of vastness, diversity, and unsimultaneity was at least as burdensome as the enduring deficit of democratic thought and praxis.

Considering this extreme situation, and especially allowing for Russia’s ingrained historical-political traditions, the choice was never really between democracy and despotism, but between different forms of authoritarian rule. Any Russian government was bound to be a severe emergency government prone and indeed obliged to resort to violence as a provisional instrument of rule, and a Bolshevik government would merely be more inclined to do so than a government formed by leaders with a different historical understanding, doctrinal conception, and personal experience of revolution.4

This background conditioned the nature and practice of the Bolsheviks’ founding violence and enforcement terror of 1917–21, including of its chief executive agency: the Cheka. At the outset, the Cheka was conceived as part of a stopgap for the broken armor—bureaucracy, judiciary, police, army—of the Russian state. Cities and towns experienced the equivalent of the wild land seizures and attacks on notables in the countryside. There was a wildfire of looting of the property of the wealthy classes as well as an explosion of avenging violence against members of the old power elite, especially former government officials and army officers. Further, with prisons and courts crippled, society was overrun by criminals and blackmarketeers who, in turn, provoked wild justice.5 This rampant lawlessness called for the prompt establishment of a new legal, penal, and police system. In many respects the Cheka was as much an improvisation as War Communism, which was designed less to recast the economy than to reclaim it to provide daily rations and the sinews for political and military survival. Both the Cheka and War Communism were driven by a combination of panic, fear, and pragmatism mixed with hubris, ideology, and iron will.

The development of the Cheka’s mission and organization was closely correlated with the spread and aggravation of the civil war, and so was the growth of its ideological furor. With time, and without relenting in its battle against runaway speculation, hoarding, and ordinary crime, the Cheka gave first priority to enforcing security to the rear of the fast changing battle lines of the civil war as well as to deploying special security units among the fighting forces of the Red Army and along vital rail lines and roadways.

Without any deliberate plan but simply in response to all these imperatives, the manpower of the Cheka expanded from some 2,000 men in mid-1918 to over 35,000 six months later and to about 140,000 by the end of the civil war, not counting some 100,000 frontier troops. The central headquarters, first in Petrograd and then in Moscow, eventually established and partially controlled a sprawling network of provincial, district, and local Chekas. As of March 1919 Felix Dzerzhinsky, the Cheka’s national chairman, also served as People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs, giving him direct and privileged access to Sovnarkom, which presumably defined and oversaw internal security. Gradually, with the civil war raging and calling for instant decisions and resolute actions, at all levels the Cheka tended to stretch and exceed its powers, which were typically ill-defined. Rather than turn criminals and political suspects over to what were intended to be separate revolutionary tribunals for prosecution and sentencing, the Cheka ignored and fended off outside judicial and political controls.

It is hardly surprising that “the Cheka’s original mandate… [should have been] modeled on the tsarist security police” whose practices were rooted in Russia’s authoritarian past.6 The Bolsheviks, like the Jacobins, brought back the old methods of criminal and political control, though both foreswore recourse to the old forms of torture. To be sure, there were significant differences between the respective precedents: on the one hand, the religiously fired sack of Béziers and massacre of Saint Bartholomew’s Day; on the other, the ungodly exile system in Siberia and the repressive praxis of the Okhranka. These peculiarities in turn made for distinct differences in the configuration of the two terrors, the one having the guillotine as its most distinctive emblem, the other concentration and labor camps. Nonetheless, one might say that in both cases, in Quinet’s words, “the weapons of the past … were taken out of the old arsenal … and used in the defense of the present,” with the result that “by way of the terror today’s men suddenly and unwittingly reverted to once again become the men of yesterday.”7

Almost from the beginning, concentration and labor camps were part of the Bolshevik regime’s internal security system, and they were grafted onto Russia’s age-old internal exile system, a legacy for which there was no equivalent in France. Through the centuries, the experience and memory of religious persecution and prosecution, backed by the Inquisition, left a deep imprint on France’s ways and means to “discipline and punish.” Russia’s methods, for their part, were impregnated with the profane practice of bureaucratic and arbitrary justice, closely overseen by the tsars. The Siberian exile system, dating from the later sixteenth century, was the hub of the Romanov empire’s wheel of justice. It was inaugurated by Ivan the Terrible (1533–84), who also initiated Russia’s eastward continental expansion.8 Even if unintentionally, newly opened territories became the entryway to a vast and distant “roofless prison” for “outlaws” sentenced to ssylka, or banishment and exile. Ironically, almost from the start exile to Siberia was conceived as a clement alternative to capital punishment.

During the seventeenth century, with the acquisition of huge and sparsely peopled lands in Trans-Uralia, including Siberia, ssylka rapidly became “the central and most characteristic feature of the tsarist penal system.”9 The Law Code of 1649 designated several regions in Siberia as places of “external exile” for a sweeping range of lawbreakers, including fugitive serfs and religious dissenters. By now the tsars began to realize the advantage of using ssylka along with conscription to populate and develop the empty but economically valuable Siberian spaces, which soon attracted an ever larger flow of more or less voluntary settlers as well. As early as 1662 exiles accounted for 8,000 or over ten percent of Siberia’s settler population of 70,000. It was now, too, that torments began to be inflicted on prisoners before they set out on their via dolorosa: besides being flogged with the knout, many of them suffered the mutilation of a hand, foot, ear, or nose, as well as the humiliation of being branded. Following this ordeal, many prisoners walked a full year, in leg irons, to reach their destinations, until Tsar Alexander III (1881–94) put an end to these interminable forced marches in favor of transport by ship, and later by train.10

Peter the Great updated the Siberian archipelago’s “prisons without doors” by supplementing and then surpassing ssylka with katorga, or forced labor.11 The moving eastern frontier was to be exploited for the benefit of the imperial regime. More and more convicts were put to work mining silver, gold, and salt as well as, in due course, building roads and railways. Katorga became the harshest of tsarist Russia’s six categories of penal servitude. Having survived the dual ordeal of the post-conviction torment and the wretched passage eastward, the brutalized prisoners faced a forbidding environment of life and work near the mines of Nerdinsk and Kara, and at many other sites, most of them fairly small: a population of several hundred was the norm, and several thousand the exception. Inadequate housing, clothing, and food made for a high rate of disease and mortality. Weighed down with ten-pound fetters and subject to arbitrary flogging, the convicts worked long hours. They had no time off, until 1885 when they were granted two days of rest per month. Wives were encouraged to accompany or follow their husbands, probably in the interest of colonization, since most convicts settled in the Far East upon completion of their sentences.

The long nineteenth century down through 1917 saw many changes in tsarism’s peculiar penal and political security system.12 Following the Decembrist rising of 1825 Nicholas I established the Third Section, a special political office with a corps of policemen to protect the security of state and regime. In part because of its inadequacy in the face of growing opposition, in 1880 the Third Section was abolished and all security functions were concentrated in a single police department in the Interior Ministry. The next year Alexander III reinvigorated the Okhranka, the tsarist regime’s main security organization charged with uncovering, infiltrating, and repressing the political opposition, which was increasingly forced underground and prone to terrorism. Although it was overwhelmed by the great upheaval of 1905, the Okhranka more than recovered between 1906 and 1914, when Nicholas II resumed and intensified the war against the anti-tsarist opposition, which he quickened with his own unbending policies.

The flow of convicts to Asiatic Russia continued all this time, with between 10,000 to 20,000 yearly, unevenly divided between ssylka and katorga. Although in 1801 Alexander I had abrogated the most extreme forms of cruelty, prisoners continued to be subjected to preliminary branding and knouting for several more decades.13 There are no reliable figures on the number of political prisoners among them, but according to the best estimates they never made up more than one percent.14 Indeed, they may be said to have peopled the equivalent of no more than one of the many islands of imperial Russia’s penitentiary archipelago. The politicals were neither branded nor whipped. Though they benefited from a privileged status and regimen, they experienced the rigors of the exile system and were in many different ways scarred and marked by it, including by their close if limited contact with lowborn common-law convicts. The political prisoners left a greater mark than their limited numbers warranted by virtue of their notoriety and their role in excoriating the exile system in utterly stark and terrifying terms, which left a dark and haunting imprint on the Russian and European imagination, not unlike the Inquisition.

Dostoevsky was the first of several great Russian writers and political intellectuals to probe tsarism’s peculiar prison and exile universe.15 In his twenties in St. Petersburg Dostoevsky became involved with a half-secret discussion group of young and well-born critics of runaway autocracy. The Third Section being on the watch, Dostoevsky was arrested. He spent eight months in a prison of the Peter and Paul Fortress before, at Christmas 1849, beginning his journey to Omsk, mostly by sledge though weighted down by leg irons. His Memoirs from the House of the Dead (1861) is a searing autobiographical but also creatively imaginative telling of his four years of hard labor and military service in this western Siberian city. Dostoevsky’s account was followed by those of Chekov, Tolstoy, Bakunin, and Kropotkin.

Solzhenitsyn, too, stands very much in this tradition.16 In The Gulag Archipelago he briefly discusses the history of the exile system, with particular attention to the privileged place of the political prisoners in it. His main concern is to extenuate the evils of the tsarist penal and exile system in comparison with those of the Soviet Gulag. In fact, he means to demonstrate a fundamental discontinuity between the one and the other, making the Gulag exclusively the product of the Communist ideology and the villainy of Lenin and Stalin, without significant roots and parallels in Russia’s past. Even so, by describing, however synoptically, the “somber power of exile” and the “miserably clothed, branded, and starving” victims of ssylka and katorga under the tsars, Solzhenitsyn concedes elements of historical persistence at the same time that he tells the story in the dire and bitter accents of Dostoevsky.

The Bolsheviks themselves were influenced by Russia’s prison and exile literature, all the more so because for some of them, as for not a few Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, it spoke to their own personal experiences. While as of the late nineteenth century the Romanov regime willfully used ssylka to deter and intimidate radical critics and revolutionaries, these, for their part, held it up as one of tsarism’s basest badges of infamy. Even if Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, and Bukharin knew the penal and exile system from the inside—albeit under tolerable conditions—they certainly took it for granted that it would be eliminated with the birth of a new Russia. And, in fact, the first Provisional Government abolished it, along with the tsarist police and Okhranka. Eventually the exigencies of the struggle against criminals as well as enemies at home and abroad prompted the Bolsheviks to reach back, selectively, into Russia’s storehouse of political strategies and weapons of judicial and political control, and ssylka and katorga were reshaped to serve the pressing needs of the moment. Presently Paul Miliukov, perhaps the savviest Constitutional Democrat, noted that Bolshevism was a hybrid of “very advanced European theory … [and] genuinely as well as deeply rooted Russian” praxis which rather than “break with the ‘ancien régime,’ reasserts Russia’s past in the present.” In an evocative simile, Miliukov suggested that just “as geological upheavals bring the lower strata of the earth to the surface as evidence of the early ages of our planet, so Russian Bolshevism, by discarding the thin upper social layer, has laid bare the uncultured and unorganized substratum of Russian historical life.”17

To come to terms with the Cheka-run concentration and labor camps during the first terror of the Russian Revolution, it is of course important not to go too far in tracing their genealogy and etiology backward into the past. It is equally important, however, not to read their early history in terms of subsequent developments, notably of the Soviet Gulag after 1929 and of the Nazi concentration camps after 1933 and extermination camps after 1941. The term “concentration camp” originated with the colonial wars of the fin de siècle: Spain set up concentration camps to hold enemy prisoners and civilians in Cuba, the United States in the Philippines, and England in South Africa.18 In all three cases the internment camps were established in wartime, overseas, and as a concomitant of military operations. None of the outside armies faced politically organized ideological enemies to the rear of their lines, which meant that their prisoners, both military and civilian, suffered the miseries of emergency detention rather than institutionalized and willful mistreatment or forced labor. With victory the camps were closed, also because what little there was of insurgent resistance came to an end.

Later on, the concentration camps of post-1929 Soviet Russia and post-1933 Nazi Germany were initially political camps started in peace time and in the absence of active civil war at home. Whereas from the outset the Gulag had the dual mission of enforcing political control and of driving economic growth through the exploitation of the forced labor of its inmates, the concentration camps of the Third Reich did not assume an economic role—nor a genocidal turn—until well after the outbreak of war in 1939.

For their part the camps of the Russian Revolution’s first terror were set up in the midst of combined foreign and civil war. Both the external and internal conflicts were highly ideologized, with the result that unlike during the Spanish-American and Boer wars, some of the enemies who were imprisoned in camps were seen as being distinctly political. As for their impressment for forced labor, it was related to the fighting of essentially defensive domestic and foreign struggles rather than to a project of either economic mastery or foreign territorial conquest. But it would seem that the Bolsheviks’ readiness to use the labor of camp inmates in the emergency of 1917 to 1921 was conditioned by Russia’s past experience with katorga, just as the harsh living and working conditions in these camps were due to the extreme rigors of war and civil war rather than to a blueprint for systematic punishment or exploitation, let alone extermination, “there being no Soviet Treblinka.”19

The aristocratic reaction in France, reflected in Louis XVI’s repeal of the Maupeau reform in the early 1770s, was mild compared to that in Russia during the decade before 1917. Those were the years in which Nicholas II rescinded many of the liberalizing concessions he had grudgingly made in 1905. By the outbreak of war in 1914 the constitutional experiment had been diluted, the tsar and his acolytes having severely restricted the franchise and civil liberties, as well as broken the Duma. Significantly, this reversal coincided with the growth of a new right sworn to violence, which had the blessing of the Court. As noted, during the Very Great War military misfortune and futility, reckoned in millions of casualties and utter economic exhaustion, once again undermined the old order, and by early 1917 Russia’s political and civil society entered a time of unprecedented troubles.

Not surprisingly, the workers of Petrograd, including women textile workers, were in the forefront of the revolt of late February and early March.20 Clamoring for bread, peace, and the end of autocracy, their swelling strike movement was largely spontaneous. At first, the prospects were dim, as troops loyal to the tsar kept firing upon them, taking numerous lives. But the remonstrants stayed the course, some of them rushing such emblems of repressive state power as police stations, prisons, and court houses. Others wrought their vengeance on public officials, “hunting down, lynching, and brutally killing” policemen.21In Petrograd alone there were some 1,400 dead and wounded, about half of them military personnel.22 It was only with the mutiny of several local army garrisons, urged on by junior officers, that the insurgence stood fair to succeed: the muzhiks in military uniforms who defied the order to open fire on civilians rose against the conceit of their imperial officers, which they considered of a piece with the arrogance of the landed gentry. At any rate, workers and soldiers joined hands to occupy public buildings and seize arms for what quickly turned into a full-scale insurrection. Meanwhile the Octobrists and Kadets, who finally prevailed on Nicholas II to abdicate and Grand Duke Michael to renounce the throne, formed a provisional committee to restore order, composed of thirteen Duma members. Their aim was to fill the emergent political vacuum and prevent a runaway fragmentation of sovereignty. At the same time, the Menshevik Duma deputies, in the spirit of 1905, took the lead in forming a provisional Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers—in which peasant-soldiers greatly outnumbered proletarian workers—to organize and channel the rebellion. Even if their ultimate political and social objectives as well as their worldviews were very much at variance, Kadets and Mensheviks, one and all fervent westernizers, agreed on the instant establishment of a “bourgeois-liberal” government and the early election of a constituent assembly. Such was the origin and mission of the provisional governments headed first by Prince Lvov and then Kerensky.

But as mentioned before, the Kadets and Mensheviks, now joined by the Socialist Revolutionaries, had one other common, perhaps overriding aim: not unlike the bulk of Russia’s traditional power elite, they proposed to see the war through to victory on the side of the Allies. Admittedly, the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries proceeded to exhort all the world to move toward a peace without annexations and indemnities, to be secured by timely negotiations. But pending this unlikely political and diplomatic reconfiguration, the grueling war continued, with devastating social and political consequences.

Under the circumstances the coalition cabinets headed by Lvov and Kerensky could be little more than emergency governments with a limited and hesitant reformist reach. Still, Russia’s new rulers promulgated essential freedoms: association, assembly, speech, press, and religion; as well as disestablishment, amnesty, and the end of capital punishment. But these bold steps, in the spirit of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, touched more sympathetic chords in urban than rural Russia, which had altogether different priorities, notably immediate peace and, above all, land reform. Indeed, especially the Kadets, but also many Mensheviks, dodged the land question, so that at this juncture Russia’s embryonic reformist regime produced nothing comparable to France’s dramatic night of August 4, 1789, which had brought the abrogation of the “feudal” rights and privileges of the nobility and clergy. Obsessed with the imperatives of war, the Lvov and Kerensky governments sought to restabilize rather than reform Russia’s political and civil society, thereby muting their millenarian promise. A certain reading of the dynamics of the French Revolution fortified the members of successive provisional governments in their resolve to prevent any further radicalization favorable to the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, even at the risk of fostering it with their own inordinate caution. Meanwhile the election of the projected Constituent Assembly remained in suspense.

Beginning with the resignation of A. I. Guchkov, leader of the Octobrists, and the removal of Miliukov on May 1, 1917, when Kerensky became war minister, the Kadets kept yielding cabinet positions to the non-Bolshevik left. At the same time that this faction-ridden left gained ground in the straitened state executive, in mid-June it found a home in the First All-Russian Congress of Workers and Soldiers Deputies, a potential rival or alternative to tomorrow’s Constituent Assembly. Except for the Bolsheviks, the members of this would-be people’s parliament endorsed the policies of the provisional governments. But the country’s skyrocketing economic distress and war weariness worked in favor of the dissident and far left, as did the fiasco of Kerensky’s politically inspired military offensive on the Galician front in mid-June. Urged upon Petrograd by the Allies, this bold stroke, which cost several hundred thousand lives, was a desperate gamble: an improbable military victory was to be used to consolidate the provisional regime, above all by redeeming the army, without which there was no restoring law and order.23

Partly fueled by indignation about the continuing military unreason, the violent anti-government demonstrations of July 3–5, 1917, in Petrograd were primarily carried by the left.24 The furor was largely spontaneous: considering direct action premature, the leaders of the Bolshevik party and Petrograd Soviet followed rather than led the soldiers, sailors, factory workers, and city poor who took to the streets. Because the riotous crowds lacked discipline and leadership, the provisional government’s sparse police and military forces were sufficient to disperse them, with minimal casualties on both sides.

The sequel of these journées was mounting discord between the Kadets and the non-Bolshevik left over how to deal with the irrepressible crisis.25 Lvov and four Kadet ministers resigned as Kerensky assumed the premiership to rule with a coalition in which non-Socialists were now in the minority. He vowed to push for a non-annexationist peace, a constituent assembly, and land reform. At the same time, Kerensky ordered the arrest of leading Bolsheviks, though Lenin and several of his closest associates managed to flee abroad or go underground. He also directed General Kornilov to steel the army. Even so, and as part of a conservative backlash, the Kadets served notice that they were more than ever opposed to a soft peace, social reform, and power-sharing with the Soviets. Indeed, in the wake of the failed June offensive and the portentous July days, the Kadets ceased to support reform as an antidote to further radicalization. Unlike Kerensky, they abandoned the search for a third way or force between the far left and far right.

Not a few prominent Kadets along with liberals and conservatives silently cheered when in late August General Kornilov, with broad backing by senior officers, ordered select regiments to march on Petrograd either to stiffen Kerensky’s resolve to stand fast or to establish a government of national salvation controlled by the military.26 Having tempted the devil, Kerensky dismissed Kornilov and summoned all the forces of movement to rise in defense of the Revolution. These forces rallied under the banner of a Committee for the Struggle Against the Counterrevolution, supported by the Soviet as well as the Bolsheviks, though Lenin stressed that the workers were mounting the barricades to protect the Revolution, not the government. In the meantime the cabinet had invested Kerensky with special, not to say dictatorial, powers to meet the emergency.

Once the challenge from the military was checked, there was yet another cabinet struggle. The third provisional government, headed by Kerensky, was dominated by moderate Mensheviks and right Socialist Revolutionaries. This cabinet was weaker than its predecessors, not least because of the explicit opposition of both the restless forces of order, including the Kadets, and the impatient Bolsheviks.

Unable or unwilling to extricate Russia from the ruinous war and to address the burning land problem, Kerensky simply could not find a social base for his phantasmagoric third way. Conditions were going from bad to worse on the front, in the major cities, and in the countryside, with the result that the disaffection of workers and peasants expanded and quickened. The Bolsheviks were the major beneficiaries of the Kornilov affair. Legitimated as a result of having been asked and armed to help in the defense of the Revolution, they redoubled their agitation and organizing efforts. In turn, the officers corps emerged as the vanguard and nerve center of the inevitable counterrevolution. With little political power, moral authority, and repressive force, the third coalition government was helpless. Here if ever was a situation to which the words of Yeats apply: “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold.”27

In late September and early October, when Lenin, seconded by Trotsky, convinced the inner circle of Bolsheviks to launch an armed uprising, he knew that famine, war weariness, and fear of another right-wing coup would translate into broad popular sympathy or backing for his wager. The Bolsheviks also assumed that few, if any, police and army detachments were likely to stand by Kerensky. Indeed, there were practically no protective forces when on October 25 Bolshevik activists rushed the Winter Palace to arrest the cabinet members, who were briefly held at the Peter and Paul Fortress before being released. While the Red Guards took control of Petrograd, Kerensky hastened off to Pskov, the headquarters of the northern front, expecting to rally loyal troops. But he found none, except for some l,000 badly armed Cossacks whom General Peter N. Krasnov agreed to rush in the direction of Petrograd. They reached Gatchina, a southern suburb, on October 27. Three days later, “a motley army [of approximately 10,000 men] made up of workers’ detachments, soldiers of the Petrograd garrison, and Baltic sailors” defeated Krasnov’s forces at Pulkovo Heights, with casualties on both sides.28 Krasnov was captured, and Kerensky fled to England. It was a measure of the powerlessness of Kerensky’s government that during the “Ten Days That Shook the World” there were only several dozen casualties in the capital of the new Great Revolution. In Moscow, however, there was considerable resistance. For an entire week assorted officers, military cadets, and right-wing Socialist Revolutionaries shielded the provisional government, with the result that several hundred people were killed. Still, all things considered, the Bolshevik takeover was relatively bloodless, certainly compared to the February uprising.

It was now the turn of the Bolsheviks to set up yet another—a fourth—provisional government. But theirs was to be a “Workers’ and Peasants’ Government,” to be run by a Council of People’s Commissars chaired by Lenin, with Trotsky serving as Commissar for Foreign Affairs. They dropped any pretense of practicing the reason of state and of standing above class or interest. The Bolsheviks had pressed for an early meeting of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, and it opened on October 25–26, in the midst of their bid for power. In addition to looking to avoid the strains of dual power, they sought ratification of their immediate and short-term program: make peace; distribute land; eliminate food shortages; and elect a constituent assembly. This last point was equivocal in that it implied that ultimately power would be vested in a constituent assembly, which clashed with the Bolsheviks’ cry for “all power to the soviets.”

In any case, the Congress of Soviets approved Lenin’s sweeping Decree On Peace calling for an instant negotiated end of the war “without annexations and indemnities.” There followed an equally radical decree expropriating the land of the landlords, imperial family, Orthodox Church, and state. The land was transferred to latter-day mirs (village communes) or new-model soviets for distribution, equally, to peasants pledged to work their small plots without hired labor. On January 18 the Decree Socializing the Land confirmed this vast redistribution, without compensation, and reiterated that “the right to use the land belongs to him who cultivates it with his own labor.” With these rescripts, which appropriated the platform of the Socialist Revolutionaries, the Bolsheviks meant to broaden their social and political base beyond the urban proletariat. But no less important, they gave evidence of their practical reason: countless peasants having long since seized the land they had now and forever considered their own, the Bolsheviks legitimated the revolution in the countryside which had not been of their doing. Indeed, by recognizing the wild land seizures, the Congress of Soviets and Bolshevik leaders grounded the Russian Revolution much as the National Assembly, moved by the grande peur, had grounded the French Revolution in August 1789.29 Both times the city took the first step, but in countries that were over 85 percent peasant, there was no continuing without the village.

Having spoken on peace and land, the Congress of Soviets elected a Bolshevik-dominated executive committee and approved the new provisional government. In so doing it ratified Lenin’s opening programmatic declaration addressed to “All Workers, Soldiers, and Peasants,” whose interests now moved to the top of the revolutionary agenda.30 Except for “ensuring the convocation of the Constituent Assembly on the date set,” the new emphasis was—pace Hannah Arendt—squarely on the social question, with priority for “the transfer of all land without compensation” to peasants and “the establishment of control over industry by workers.” This new course was contingent on securing an immediate and non-annexationist peace, just as the previous course had been tied to staying in the war for war aims fixed before 1917. Indeed, the issue of war and peace remained altogether crucial. The exigencies of war were certain to seriously impede the embryonic Bolshevik regime’s efforts to implement its far-reaching program: on the one hand, the Declaration of the Rights of the Toiling and Exploited People of January 16, 1918, signaled a radical break with the past and a headlong rush into a new future, giving Lenin’s provisional government the millenarian urge which the preceding provisional governments had lacked or abjured; on the other, in face of an ever more refractory time of troubles there was no dispensing with a dictature de détresse. The switches were set for a governance severely torn between contingency and ideology, with the new decision makers mindful of the perils of both pressing emergencies and overweening innovations.

With the world collapsing about them, none of Russia’s provisional governments gave the Constituent Assembly top priority. Both the Kadets and the Mensheviks were wary of elections by universal manhood suffrage, in which they knew they could not fare well.31 At first set for September 17, 1917, the elections were postponed to November 12. By then, eight months after the fall of the Romanovs, the Bolsheviks were in power. But, as noted, they had pledged to allow the elections to go forward.

About 40 million votes were cast, the rate of participation being between 50 and 60 percent.32 With about 16 million votes, or 40 percent of the total, the Socialist Revolutionaries secured some 400 seats. The Bolsheviks were second, with about 10 million votes, or 24 percent, which gave them 170 deputies. The outcome confirmed the worst fears of the liberal and social democrats: the Kadets captured only about 2 million votes and 17 seats; the Mensheviks received 1.5 million votes—half of them in Georgia—and 16 seats. The two parties combined accounted for less than 10 percent of the popular vote and 4 percent of the seats.

Perhaps most significantly, the throne and altar, as well as the landlords, were left high and dry, the peasants having voted massively for the Socialist Revolutionaries. While the latter were strongly carried by the countryside, they won only limited support in the cities, taking no more than 8 percent of the vote in Moscow and 16 percent in Petrograd. The Bolsheviks, for their part, scored well in urban Russia, gaining close to 50 percent of the vote in the “two capitals.” Having played on war weariness, they also polled about half the votes in the army garrisons to the rear. As things turned out, the Bolsheviks had a stronger social base than their overall electoral score suggests, especially in 1917–18, when the Revolution’s commanding political heights were in urban Russia. Even so, although they showed unexpected strength, they would have been in no position to govern democratically, assuming they had wanted to. They did, however, shore up their cramped position by prevailing on the left Socialist Revolutionaries to be their coalition partners, which brought them the support of 40 additional deputies and opened them to the peasantry, in keeping with their land policy.

By the time the Constituent Assembly convened on January 5, 1918, the civil war was getting under way. While the Bolsheviks were not really surprised by the incipient resistance of the White Guards, they were outraged that the Kadets should so fully side with them. Indeed, the Kadets, unlike the Mensheviks, made common cause with the greatest losers of the elections, the Whites, who saw no contradiction between abjuring electoral politics, which put them at a disadvantage, and championing the cause of a free Constituent Assembly. In any case, on December 1, 1917, Lenin called for the outlawing of the Kadets, insisting that they wanted “to simultaneously sit in the Constituent Assembly and organize civil war.” His Socialist Revolutionary partners instantly urged the Bolsheviks to “free themselves from their nightmare about the Kadets,” particularly since there were no hard and fast criteria for “identifying” them. Instead of hammering away at the Kadets’ spurious constitutionalism, the government should challenge the Constituent Assembly to vote “on questions of peace, land, and workers’ control,” with a view to turning it into a “revolutionary Convention.” Blithely ignoring this advice, the all-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets adopted a resolution denouncing the Kadets for “heading” the counterrevolution, after Lenin stressed that in “bringing forward a direct political charge against [an entire] political party” the Bolsheviks were merely following in the footsteps of “the French revolutionaries.”33

The socialists were very much divided on the eve of the opening of the Constituent Assembly in which they would occupy some 85 percent of the seats. The Bolsheviks charged that the slogan “All Power to the Constituent Assembly” embraced by the Mensheviks and moderate Socialist Revolutionaries was really intended to be read as “Down with the Soviets.”34 Clearly, Lenin meant to “counterpose the Congress of Soviets to the Constituent Assembly.” Having benefited from their campaign for the soviets, the Bolsheviks valued their symbolic force and expected to have the ascendancy in them. According to Zinoviev, “the duel between the Constituent Assembly and the Congress of Soviets … [was] a historical struggle between two revolutions, the one bourgeois and the other socialist, … the elections to the Constituent Assembly [being] a reflection of the first [i.e., the] February revolution.”35

This unseasonable Constituent Assembly convened on January 5, 1918 in Taurida Palace, with Victor Chernov, a leading Socialist Revolutionary, in the chair. In the name of the provisional minority government, Iakov Sverdlov stepped forward to move that the deputies make this government’s founding project, as put forward in the Declaration of the Rights of the Toiling and Exploited People, their working agenda. Sverdlov emphasized that just as the French Revolution had “issued the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen which … [sanctioned] the free exploitation of those not possessing the tools and means of production … [so] the Russian Revolution had to issue a declaration of rights thundering forth its own project.” When his motion was defeated by about 235 over about 145 votes in favor of a proposal to “discuss current questions of policy,” the Bolsheviks, as if according to plan, stormed out of the hall, followed by the left Socialist Revolutionaries, signaling the closing and dissolution of the Assembly.36 Not unlike Stolypin’s “coup d’état” of June 3, 1907, which had devitalized the fledgling Imperial Duma, this arrogation aroused little, if any, protest or outrage: once again there was only meager popular support for democratic principles and institutions. In particular the peasants were impervious to democratic chants, all the more so now that they were repossessing “their” land by direct action rather than legislative enactment. As for the industrial workers, who shared the peasants’ cruel disappointment with the pre-war Duma, they pinned their faith to the soviets and the factory councils. In effect, the champions of the Constituent Assembly were in no position either to raise volunteers for its defense or to mobilize the streets, the partisans of constitutional democracy being found among the classes, not the masses.37

On January 10, 1918 the Third All-Russian Congress of Soviets became the presumptive heir of the Constituent Assembly. The delegates sang the International before an orchestra struck up the Marseillaise, “to bring to recollection the historical path traversed” since 1789. This Congress promptly adopted a variant of the Declaration of the Rights of the Toiling and Exploited Peoples which the Constituent Assembly had voted down. It proclaimed, urbi et orbi, that the Russian Revolution was sworn to “end … the exploitation of man by man … and the division of society into classes”; to make “all land … public property” for transfer “to the working masses without payment … and on the basis of equal land tenure”; to establish “workers’ control”; and to promote the “right to self-determination.” This would-be ecumenical manifesto, which superseded the battle cry “peace, bread, and land,” was not without a contingent fighting agenda, in that it vowed to “crush exploiters mercilessly,” to raise an “army of working men,” and to “put an end to all secret treaties.”38

We have seen, then, that civil and political liberties were not high on the reformist agenda in the early dawn of the revolution in Russia. No less striking, the founding violence of the year 1917 was relatively limited, largely because the military was not about to keep repressing it. Indeed, to the extent that the February upheaval culminated in a “revolution from above,” the army’s senior officers were among its chief sponsors and mainstays. They sacrificed the crown to an accommodation with a legal opposition and Duma which they expected to be moderate and tractable. In any case, if there was no counterrevolutionary resistance and civil war immediately following the February days it was largely because until late August the high command supported the provisional governments, the prosecution of the war being their joint and absolute priority. First Kornilov’s defiance and then Krasnov’s military drive prefigured the unexceptional counterrevolutionary turn of the ranking generals and their political collaborators. Certainly these hard-liners were not about to rally to a government seeking an early and humiliating exit from the Very Great War as part of a strategy to consolidate and drive on the revolution. In addition to facing the trials and tribulations of Russia’s time of troubles, the Bolshevik provisional government had to confront an ominous counterrevolutionary resistance aided from abroad.

Petrograd and Moscow were not promising sites for military resistance. Probably for reasons of logistics as well as because of the prospect of Cossack recruits, the center of opposition moved from the army’s general headquarters at Mogilev, east of Minsk, to the Don territories in the south. It was also near Mogilev, in a monastery at Bykhov, that Kornilov was under house arrest along with the other generals who had supported his dare, among them Alexeev, Denikin, Lukomsky, and Romanovsky. Not unlike Kerensky, Lenin treated these star prisoners leniently. Along with the members of Kerensky’s cabinet, General Krasnov was released a few days after October 25. In exchange he gave “his ‘word of honor’ that he would not fight against the Soviet regime,” which he instantly broke. In any case, these were the senior officers who formed the original commanding core of the White Guards.39

General Mikhail Alexeev, the tsar’s chief of staff since 1915, left to go south in early November, and settled at Novocherkassk, northeast of Rostov on the Sea of Azov. By about December 10 he gathered a force of at least 600 men, most of them officers, who were prototypical of the future Volunteer Armies. After escaping from their prison-monastery, the other “Bykhov generals” arrived a few days later, each having made the journey on his own.40

The chief of the general staff, General Dukhonin, decided not to take flight. From headquarters at Mogilev he “appealed to the army to remain loyal to the [ousted] Provisional Government and to put an end to Bolshevik violence.”41 He was taken in custody by a local soviet of soldiers before Nikolai Krylenko, with a company of men, came to arrest and take him to Petrograd. Apparently Krylenko failed to restrain an excited crowd, with the result that Dukhonin was shot and his body savagely mutilated. That was December 3, the day cease-fire negotiations with the Central Powers started at Brest-Litovsk. After a skeletal constabulary of Red Guards seized control of Rostov, on December 15 Alexeev’s embryonic Volunteer Army dislodged them in a “short but fierce bout of street fighting.” With this military action, which gave them their “baptism of fire,” the Whites fired the “first shots” in Russia’s civil war.42

From the outset the generals and the many officers were divided into two factions: one rallied around General Kornilov, who was personally the most ambitious and militarily the most daring; the other around the more sober-minded General Alexeev. In turn, both were at odds with generals A. M. Kaledin and Krasnov, the two main Cossack chiefs. In particular Kaledin, as hetman of the Don Cossacks, was a jealous guardian of his people’s autonomy.

In the meantime these White and Cossack generals were joined at Novocherkassk by kindred political leaders, among them Fedorov, Miliukov, Rodzysenko, Struve, and Prince F. N. Trubetskoi. With the Kadets among them setting the tone, they pressed the squabbling officers to settle their differences, insisting that otherwise they could not win support either in Russia or abroad, among the Allies. Persuaded that their enemies’ enemies were their friends, on December 18, 1917, one and all agreed on a troika: Kornilov was to be in charge of all White military forces; Alexeev of civil government and relations with the Allies; and Kaledin of the administration of the Don territories as well as of Cossack military forces.43

Although there was incidental talk of civil liberties to spare the sensibilities of both liberals and Allies, there was no disguising that the project of this provisional political and military authority was autocratic and ultranationalist, and ultimately counterrevolutionary. Even so, leading Kadets rallied around the generals, who were anything but unpolitical, thereby raising the White Guards’ prestige, especially abroad.

Not surprisingly, and with good reason, the untried Bolshevik government forthwith concluded that the Cossack territories of the Don and the adjoining eastern Ukraine were likely to become a major staging ground of resistance. Indeed, within less than two months after the Bolshevik takeover White and Cossack forces were beginning to shoulder arms. Presently Lenin sent Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, who had played an important military role in Petrograd during and immediately following Red October, to direct operations on the southern front.44

This embryonic counterrevolutionary mobilization coincided with Sovnarkom’s initial steps toward the deliberate use of enforcement terror. Sensitized by the Jacobin experience, the Bolshevik leaders were predisposed to such terror, considering it immanent to revolutionary practice. Had there been no “evidence” of implacable resistance immediately following their takeover—which would have been contrary to the “logic” of the situation—the Bolsheviks most likely would have held back on terror. Under the circumstances, however, the issue, for them, was not so much “one of ‘principle’ ” as of “form” and “degree,” and hence of “expediency.”45 In any case, on November 28, a decree of the Council of People’s Commissars, signed by Lenin, outlawed the Kadet party. Designated “enemies of the people,” its members became “liable to arrest and trial by Revolutionary Tribunals.” Two days later, on November 30, another decree “declared that civil war had broken out under the direction of the liberal Kadet Party.”46 Trotsky had good reason to charge the “central committee” of the Kadets with being “the political headquarters of the White Guards,” although it was gratuitous for him to add that they directed “the recruitment of officers for Kornilov and Kaledin.”47 At any rate, Trotsky announced the arrest of their “chiefs” and the surveillance of “their followers in the provinces.” Claiming these steps to be “a modest beginning,” he recalled that “at the time of the French Revolution the Jacobins had guillotined more honest men than these for obstructing the people’s will.” He hastened to add, however, that “we have executed nobody and have no intention of doing so.”48 Although the left Socialist Revolutionaries agreed that the Kadets had joined the enemy camp, they cautioned that “to condemn an entire category comprising countless innocent individuals was to create an all too convenient scapegoat for the sins of the bourgeoisie and a dangerous precedent for other hapless parties.”49

It is worth stressing that throughout the civil war the bulk of the terror, and the worst of it, was closely correlated with the fighting between the Reds and the Whites. It was much more part of military operations than of political battles against real or perceived enemies and conspiracies. Clearly, the bloodletting of the first terror in the Russian Revolution, like that in the French Revolution, was civil war–related. Although this terror was not preprogrammed by the main contestants, their principal spokesmen proclaimed it nearly from the outset. To be sure, the Bolsheviks’ rhetoric of terror was impregnated with the language of class warfare. But their excoriation of the bourgeoisie, landowners, and rural petty bourgeoisie was inseparable from their denunciation of the commanders of the White Armies and their foreign backers. Trotsky called for measures to “wipe off the face of the earth the counterrevolution of the Cossack generals and the Kadet bourgeoisie.”50 But if, as Quinet suggests, the spiral of terror results from the “shock of two irreconcilable elements … and of two opposite electric currents,”51 then the terrorist rhetoric of the anti-Bolshevik camp cannot be ignored or minimized. As Antonov-Ovseenko took charge of the Red Guards in southeastern Russia, and before the Red Army was organized, Kornilov told his associates that “the greater the terror, the greater our victories.” Shortly thereafter he vowed that “[w]e must save Russia … even if we have to set fire to half the country and shed the blood of three-fourths of all the Russians.”52 In March 1919 Admiral Kolchak ordered one of his generals “to follow the example of the Japanese who, in the Amur region, had exterminated the local population.”53 No doubt a White colonel spoke not only for himself when he held that the biblical injunction “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” was too mild for the Bolsheviks, who would yield to nothing less than “two eyes for one, and all teeth for one.”54 Eventually even General Wrangel saw the White Guards wielding “the cruel sword of vengeance” rather than bringing “pardon and peace.”55

As in the early fighting of the Vendée, in the first engagements of the civil war in southern and southeastern Russia both sides committed atrocities which were neither ordered nor reproved by their respective political or military superiors. Around mid-January 1918 in Taganrog, a small port about 45 miles west of Rostov, White forces “blinded and mutilated” a group of allegedly “Bolshevik factory workers … before burying them alive.”56 When retaking the town, Antonov-Ovseenko’s Red Guards more than matched this ferocity: although they had negotiated a cease-fire “with [the] cadets of the [local] military academy …, [they] proceeded to execute them cruelly, … [throwing] a batch of fifty …, bound hand and foot, into the blast furnaces of a local factory.”57 Denikin later remembered that around this time in this same region he had seen, first hand, “eight tortured bodies of volunteers … [who] had been beaten and cut up so badly, and their faces so disfigured, that their grief-stricken relatives could scarcely recognize them.”58

It would seem that there were few, if any, links between this violence of the first hour, which was wild and inherent to civil war, and the incipient enforcement terror, which was intentional and inherent to revolution. To be sure, unlike Robespierre and Saint-Just before 1789, Lenin and Trotsky had weighed and “experienced” the role of revolutionary violence and terror before 1917, with the result that on this score they did not start their rule with a tabula rasa. For them it stood to reason that terror was immanent in the dialectics of revolution and counterrevolution. Haunted, above all, by the specter of a fierce backlash of the sort that had struck Russia after 1905, the Bolsheviks had few qualms about using terror to thwart this historical possibility, nay probability. This fear and resolve became obsessive once the socialist revolution miscarried in central and western Europe, since it foreshadowed greater foreign support for the Whites than the repressive tsarist regime had enjoyed between 1905 and 1917. Indeed, the bitter memory of Sergei Witte and Peter Stolypin explains, in large part, the Bolsheviks’ inordinate disquiet about Paul Miliukov and the Kadets.

In the summer of 1917 Lenin overconfidently anticipated a Europe-wide revolution, and hence a favorable international climate for the unfolding revolution in Russia. That was the time he averred that “the ‘Jacobins’ of the twentieth century would not guillotine the capitalists, because to imitate a worthy model was not to copy it.” Lenin seemed confident that in his time it would suffice “to arrest 50 or 100 magnates of banking capital for a few weeks … and to place the banks, the syndicate of bankers, and the businessmen ‘working’ for the state under the control of workers.”59 To be sure, the day following the Bolshevik takeover Lenin wondered how “one can make a revolution without firing squads,” since during the civil war, with each side determined to prevail, mere “imprisonment” would be futile.60 But on November 4 he held, albeit cautiously, that “we have not resorted … to the terrorism of the French revolutionaries who guillotined unarmed men,” adding that he hoped not to have to “resort to [terror], because we have strength on our side.”61 Even as late as November 1918, when the friend-enemy dissociation was rampant, Lenin claimed, not unreasonably, that “[w]e are arresting but we are not resorting to terror,” notably against enemy brothers.62

In the meantime, however, the rhetorical terror soared as the opposing sides anathematized and threatened each other, in addition to charging each other with casting the first stone. During the “first weeks of the revolution” it was Trotsky who made the “most militant pronouncements.”63 Immediately following the armed skirmishes attending the takeover in Petrograd, he served notice that for every Bolshevik worker or soldier captured by the enemy the new government would “demand five [of the military] cadets … we hold [as] prisoners and hostages.” Indeed, Trotsky was of the view that “we shall not enter into the kingdom of socialism in white gloves on a polished floor.” When the new regime’s harsh security measures were challenged in the Soviet Executive, Trotsky rejoined that “demands to forgo all repression in time of civil war were demands to abandon the civil war.” He spoke in this same vein shortly after the proscription of the Kadets, which he characterized as a “mild terror … against our class enemies.” On this occasion Trotsky warned that this “terror [would] assume very violent forms, after the example of the great French Revolution,” within less than a month, when “not merely jail but the guillotine [will be] ready for our enemies.”64 Lenin nodded with approval, charging that the “bourgeoisie, the landowners, and the rich classes, desperate … to undermine the Revolution, … were preparing to commit the most heinous crimes,” including the “sabotage of food distribution” threatening “millions of people with famine.”65

This was the spirit in which Sovnarkom moved to establish the Cheka, or All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for the Struggle Against Counterrevolution and Sabotage. It is characteristic of the history of the Cheka in the civil war that its creation was not a premeditated step. Rather, it was precipitated by a strike of state and banking employees. On December 19 Lenin asked Felix Dzerzhinsky “to establish a special commission to examine the possibility of combating such a strike by the most energetic revolutionary measures, and to determine methods of suppressing malicious sabotage.” Immediately before turning to Dzerzhinsky, Lenin had expressed his confidence that the revolution would find a “Fouquier-Tinville … of staunch proletarian Jacobin” temperament qualified “to tame the encroaching counterrevolution.”66 Fouquier-Tinville had been the chief prosecutor of the Revolutionary Tribunal during the French Revolution.

On December 20 the Council of People’s Commissars approved Dzerzhinsky’s draft proposal for a commission to “suppress and liquidate all attempts and acts of counterrevolution and sabotage; … to hand over for trial by revolutionary tribunals all saboteurs and counterrevolutionaries; and to work out means of combating them.” The Cheka was “to devote prime attention to the press, to sabotage, to the Kadets, Right SRs [Socialist Revolutionaries], saboteurs, and strikers.” As for the “measures” to be used, the text specified “confiscation, expulsion from domicile, deprivation of ration cards, publication of lists of enemies of the people, etc.”67 Dzerzhinsky was appointed chairman of the commission. Local soviets were urged to set up their own branches and to provide the center with information “about organizations and persons whose activities are harmful to the Revolution.” Presently Dzerzhinsky ordered that a system of revolutionary tribunals be set up “to investigate and try offenses which bear the character of sabotage and counterrevolution.”68

It bears repeating that the Cheka was put in place at a time when “the Cossack enemies and other ‘White’ forces were already mustering in southeastern Russia; Ukraine … was in a state of all but open hostilities against the Soviet power; [and] the Germans, in spite of the armistice, were a standing threat in the west.”69 In addition, the army and economy continued to fall to pieces.

Significantly, at the start the Cheka was less a political organ than a makeshift police and judiciary filling the vacuum resulting from the spontaneous decomposition and deliberate dismantlement of the old legal system. The pre-Bolshevik provisional governments, especially the first one, had released thousands of common-law criminals and political prisoners, and where “they acted slowly or released only political prisoners” the streets had forced the opening of jails. This emptying of prisons and break up of the tsarist police went hand in hand with the abolition of the death penalty, the Siberian exile system, and the Okhranka. It was, of course, much easier to liquidate the old legal and police establishment than to put in place a new one, in tune with the new dawn. With authority and law reduced to a skeleton, the successive provisional governments had to proceed on two fronts: to design and establish a new system of surveiller et punir; and to set up, overnight, a temporary judicial and police system—martial law writ large—to deal with the spiraling emergency. The paralysis of criminal justice continued even as Kerensky, starting in July, arrested first Bolsheviks and then the generals of the Kornilov affair.70

It is not incidental that on the very first day of Bolshevik rule the Military Revolutionary Committee posted and distributed a handbill in Petrograd calling on the people to “detain hooligans and Black Hundred agitators and bring them to commissars of the Soviet in the nearest military unit.” This warrant included a warning that “criminals responsible” for causing “confusion, robbery, bloodshed, or shooting … would be wiped off the face of the earth.” On November 10 this same committee announced that it “would not tolerate any violation of revolutionary law and order,” a special military revolutionary court being primed to deal “mercilessly … with thievery, robbery, marauding, and attempts at pogroms.”71 The situation continued to go from bad to worse in both town and country. In Moscow in 1918 the rate of robbery and murder rose to between ten and fifteen times the prewar level. Not surprisingly, Lenin “reserved his fiercest anathemas for speculators and wreckers on the economic front.”72 Indeed, they were on a par with those directed against counterrevolutionaries, spies, and pogromists. By mid-April Lenin expressed a view widely shared in the Commissariat of Justice, directed by Socialist Revolutionaries, that to check “increases in crime, hooliganism, bribery, speculation, outrages of all kinds … we need time and we need an iron hand.”73 In the beginning the Cheka’s security operatives and tribunals prosecuted robbers, black marketeers, and thugs, with the result that the “early death sentences of the Cheka were imposed on bandits and criminals.”74 These executions, which apparently became a daily affair, disheartened Gorky, who wondered whether the Revolution, harbinger of a fresh start, would know how to “change the bestial Russian way of life,” of which he was a persistent but skeptical censor.75

At this critical juncture the Bolsheviks’ “almost every step … was either a reaction to some pressing emergency or a reprisal for some action or threatened action against them.”76 The incipient terror quickened and broadened its reach in correlation with the exigencies of both civil and foreign war, as well as diplomacy. On February 21, 1918, Sovnarkom issued a declaration warning of German invasion. Subsequently titled “The Socialist Fatherland is in Danger,”77 this notice recalled the French National Assembly’s decree of July 1792 declaring la patrie en danger. Within twenty-four hours the Cheka ordered all local soviets “to seek out, arrest, and shoot immediately all members … connected in one form or another with counterrevolutionary organizations …, enemy agents and spies, counterrevolutionary agitators, speculators, organizers of revolt … against the Soviet government, those going to the Don to join the … Kaledin-Kornilov band and the Polish counterrevolutionary bourgeoisie.” The injunction was to execute on the spot anyone “caught red-handed, in the act.”78 Significantly, on February 21, the day preceding this sweeping ukase, Sovnarkom had decided to found the Red Army, in face of Germany’s renewed military offensive on the eastern front following Trotsky’s equivocation in the peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk.

Brest-Litovsk was, without a doubt, a major hinge of the new epoch of world history. It was both cause and effect of the entanglement of revolution and war in 1917–18. In Trotsky’s graphic formulation, “the pulse of the internal relations of the revolution was not at all beating in time with the pulse of the development of its external relations.”79 Needless to say, the inescapable choice between continuing the war and terminating it instantly, and cost what it may, was highly divisive among the Bolsheviks themselves as well as between them and the left Socialist Revolutionaries. But more important, whatever the road chosen, it could not help but have momentous and unforeseeable consequences for the course of the Revolution.

The Allied and Associated Powers would not hear of a separate Russian exit from the war, whose military and political outcome remained very much in the balance.80 As for the Central Powers, notably Germany, they forced the fragile Bolshevik regime to steer between the Scylla of a ruinous dictated settlement and the Charybdis of a fierce terminal onslaught. Either way, the territorial cost to Russia would be enormous: the entire eastern and southern borderlands running from the Baltic to the Black Sea, as well as territories in the Caucasus, coveted by Turkey, were at risk.

Having signed a cease-fire with the Central Powers on December 5, 1917, which was repeatedly renewed, the Bolsheviks kept calling on the Western belligerents to join in a general negotiated peace without victory and annexations for either side. Since this insolent appeal continued to fall on deaf ears, the new rulers of Russia were left to face an impatient and imperious Germany alone, the peace negotiations to start December 22 at Brest-Litovsk.

The debate about war and peace drowned out the polemics about the dispersal of the National Assembly.81 Starting January 8, Trotsky, back from negotiations at Brest-Litovsk, pressed his “neither war nor peace” stratagem against both Lenin, who advocated an immediate peace on German terms, and Bukharin, chef-de-file of the champions of a revolutionary war against the Central Powers.

Past master of the new diplomacy of appealing directly to the peoples over the heads of their governments, Trotsky proposed to gain time for his cunning policy to work. For the long term he looked to revolution in Central Europe. For the short run he overconfidently summoned and expected German workers to pressure their government to agree to a moderate peace, and also nursed the illusion of a general strike in Austria.