I WANTED TO INVOLVE Chris Rock in this project because I am a huge fan of stand-up comedy, and Chris is one of my favorite stand-up comics today, one of the true heirs, I think, along with Dave Chappelle, to Richard Pryor, who was the funniest stand-up comedian I have ever seen—and one of the most intellectual figures in the history of comedy. (Chris Rock and Dave Chappelle are like the flip sides of Pryor—the light, satiric wit and the tragicomic dark side, the side of Pryor that walked, perilously, along the edge.) When I watch Chris perform, I am always astounded by his powers of social and political observation; by his sensitivity to the way people behave, how they actually think and feel about others and about themselves—white and black, men and women. He’s as keen a critic of our times as are any of my peers at Harvard. And I was eager to see how his family’s past might have informed his sensitivity as well as his sense of humor. I was not disappointed.

Christopher Julius Rock was born on February 7, 1965. He grew up in Brooklyn, New York, and all his earliest memories are from that city, though his family’s roots are mostly in the Deep South. His mother, Rosalie Tingman, was born on February 22, 1945, in Andrews, South Carolina, and his father, Julius Rock, was born on January 6, 1932, in nearby Charleston, South Carolina. Both Rosalie and Julius moved north when they were young, living first in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, before marrying and settling in nearby Bedford-Stuyvesant. Chris is the oldest of their six children, and he remembers his parents as being extremely hardworking people who struggled in the North to support their large family.

“My mom,” he said, “she worked with mentally handicapped kids, and sometimes she would take care of other people’s kids. So there was always a lot of kids around. My dad drove a truck. First he drove for the Rheingold Brewery for, like, fifteen years. Then he drove for the Daily News for, like, twenty years, till he died. And he drove a cab on the side. So my father always kept a job—no matter what.”

Growing up at the tail end of the civil-rights movement, Chris remembers spending quite a lot of time at home talking about race and racism with his parents. He vividly recalls his father’s devotion to Jackie Robinson and Malcolm X, as well as fights that his parents would have in their house if his mother felt that her husband “was a little too nice” to his white foreman. Though he was only a child, Chris remembers these political discussions between his parents vividly and is readily able to conjure up the complexities of that time, so very different from our own.

“It’s weird,” he said. “For me, what I remember is, there’s before hip-hop and after hip-hop. And before hip-hop, black people were just scared of white people. And literally everything you did was, you know, ‘Hey, hey, act right! There are going to be some white people here!’ I mean, when I was born, four days later, Malcolm X was shot just over in Harlem, and three years later Martin Luther King goes down. So I was born into a world where my mother just didn’t want me to get hurt, you know? And, like, her parents would tell a lot of stories about the old days and segregation. They were in South Carolina—in a little town called Andrews, where they still have a Klan parade every year. There’s still a Ku Klux Klan parade through town. It’s very kind of accepted, you know? So I grew up hearing a lot of bad-white-man stories.”

This landscape of fear is intimately familiar to black people of my generation and older. And I was interested to hear that Chris, though more than a decade younger than I am and raised in a totally different area of the country, shared many of the same experiences and feelings regarding the civil-rights era that I did—albeit from a younger man’s perspective.

There was one crucial difference, however. Chris and I attended white schools, though he was bused and I just walked down the hill, like everybody else in my neighborhood, white or black. And whereas my experience in rural West Virginia in the late 1950s was largely positive, his experience in urban Brooklyn in the early 1970s was mostly negative. Indeed, Chris claims that New York City’s busing policies “killed his spirit” as a child.

Chris Rock’s parents, Julius and Rose, were both South Carolina natives who settled in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

“When I was bused to school,” he said, “I encountered a ton of racism. ‘Nigger’ this, ‘nigger’ that. Getting beat up. It was just a bad, bad experience. I was bused from Bed-Stuy to a place called Gerritsen Beach. I was seven years old, in second grade, and I was actually bused to a neighborhood worse than the one I lived in. It was white, but if you looked at those houses and our houses, our houses sold for a lot more than theirs.

“Gerritsen Beach was very working class, very ethnic Irish-Italian, and it was just pretty badly deflating for me. On one hand, I had to go to this school far away from my house. So I got to get up an hour and a half earlier than anybody in my class, and I traveled this long distance and got treated like crap by these kids. And on the other hand, it hurt me in my own neighborhood, ’cause I didn’t know anybody in my own neighborhood, so once I walked off my block, I was a stranger in the ghetto. Which made me prey to crime. If I’d gone to school in my neighborhood, I could have maneuvered around a little more. As it was, I knew people on my block, ’cause they were on my block, but I didn’t know anybody else in the neighborhood. So once I got off the block, I got robbed.”

According to Chris, busing changed his entire life, altering his feelings about who he was and what he could accomplish. “I realized that I was black when I went to Gerritsen Beach,” he said. “It wasn’t that I didn’t know I was black before I got there. It’s just that when I got to school, it was like, ‘Oh, this isn’t good.’ My first day—I’m not going to say the girl’s name, ’cause she probably is married with kids now—but literally the first day of school they sit me down next to this little girl, and she goes, ‘You’re a nigger.’ And it hurt, ’cause I knew it was bad. And I knew that no matter what, I wasn’t going to overcome my differences—I was always gonna be a nigger to this girl. So it was very painful. Everybody learns they’re black in some way. And it’s never like, ‘Hey, we’re giving out money to the first black guy we see!’ ‘Wow! I am so lucky to be black today! Would have never got this million dollars!’ It never works out like that.”

I asked Chris if he went home and told his parents about what that little girl had said to him. He didn’t—and he’s not sure why, even today.

“I can’t even answer why,” he said. “You know? My father didn’t complain. My father went to work, and he came home, and he was obviously tired, and he was obviously beat down, and he was obviously physically exhausted, you know? I had one of those dads who couldn’t really throw a baseball with you. Two throws and he was like, ‘Ah.’ He was obviously falling apart. And my father died at fifty-five. So he was dying when he was thirty-five. But my father didn’t complain. So I didn’t complain.”

Ironically, Chris was bused to the white school in Gerritsen Beach from his Bedford-Stuyvesant home because his parents had volunteered him for it, thinking he would get a better education among whites. The end result, of course, was a disaster. Chris was so unhappy that he dropped out of high school in tenth grade. “It didn’t make any sense to keep going,” he recalled with a shrug. “I mean, it was dumb to drop out, but from the time I was in grade school to the time I was in high school, I kind of didn’t really go to school, anyway. I would just sit in the back and put my head down. I would constantly get D’s and F’s. It bored me. And it’s stupid, because the thing is, if you’re going to drop out, just drop out as soon as you can, ’cause dropping out in tenth grade, you might as well have dropped out in the second grade, ’cause you’re qualified for the exact same jobs. As a matter of fact, the guy that drops out in the second grade has a better chance of getting a job, ’cause he’s got eight years of working experience.”

Chris was bused to a white neighborhood for school, an experience he found so miserable that he dropped out of school in tenth grade.

Exploring the story further, I asked Chris if he felt that he’d developed his sense of humor from being such an outsider at school, an under-achiever who turned to comedy in the back of the classroom to mask his poor performance in the front of the classroom. I assumed that Chris was concocting jokes sitting in the back, along with the alienated kids—and that his humor would have been widely celebrated, even if his grades were not. His answer surprised me.

“I don’t know,” said Chris. “I mean, I wasn’t that funny back then. Nothing was really funny to me. My grades were horrible, and I was bored. And so, like, I was funny on my block. Sort of. ’Cause I could relax and joke around. But I wasn’t funny in school, and I was far from the funniest guy in my neighborhood. Although a lot of the guys that were funnier, you know, they’re dead. Or on drugs. So I guess I was like Jackie Robinson in the sense that Jackie Robinson was the nineteenth-best player in the Negro Leagues. So it’s like I was about the fifteenth-funniest guy in my neighborhood. But I survived. While my friends, a lot of them are on drugs. I mean, like even, I was back in my neighborhood a few years ago shooting a movie. And so I’m, like, eight blocks from my old house. This film crew is all over the block. And a couple of my friends happened to be driving by, and they stopped, and we talked, and they probably stayed four minutes. Why? ’Cause they were going to get high. They were going to the same spot that they had gone to for years. But I was never the get-high guy. So I survived, I guess.”

Chris says that, growing up, he would tell jokes to his family but that he didn’t have any idea he would one day be a comedian. In fact, as he remembers, he spent more time listening to his relatives’ jokes than making up his own—and he ended up stealing a lot of his material from them.

“I didn’t know I was a comedian when I was a kid,” he said. “I would just watch my father be funny, and my grandfather was funny, and all my uncles on my father’s side were hysterical. If I took you to a family reunion right now, you would never pick me out as the famous guy. ’Cause the personalities in my family are so big, especially from the men, my God. Women have good personalities, great personalities, too, but the men can just talk, and every one of them can hold court.”

Turning to our research, Chris and I began to explore these people who’d had such a strong influence on him. We began with his father’s line and his paternal grandparents, Allen Rock and Mary Vance. Allen was born on September 22, 1908, in Eutaville, South Carolina, and Mary was born in the same area on June 9, 1918. The two met and married in South Carolina, where Chris’s father, Julius, was born. Then, during the 1940s, the family moved north, as many black people did at the time, ending up in Brooklyn. Chris knew both of his father’s parents, Allen and Mary, very well when he was growing up. “They were great people,” he said. “My grandmother was just a real sweet typical grandmother, you know, bake you a cake, bake you some pies, fry you up some chicken. My grandfather drove a cab. And I used to hang out with him. He used to drive me around in his cab a lot of the time. I never went a week without seeing him, and sometimes I would actually end up in the cab with him driving people around. And he was a preacher, too, at a kind of a storefront church in Brooklyn.”

Chris’s grandparents, Mary Vance and Allen Rock. Chris counts his grandfather as a huge influence on him.

Chris tells me that he writes his jokes the same way his grandfather used to write his sermons. “We both just write bullet points,” he said. “My grandfather never really wrote a sermon all down. And I never really write the whole joke, ’cause I want it to come out with the passion of an argument, as opposed to, like, some written thing. I mean, things always sound written when they’re written. So I used to hang out with him, and he’d write his sermons, and to this day I write my jokes exactly the same way. He was a huge influence on me. And, you know, he cursed all the time. My grandfather the preacher. He would drive: ‘Praise the Lord, motherfuck.’ Just constant cursing. And he was one of these guys who was quick to jump out of his car when he wanted to fight somebody. We would be driving, and somebody would cut him off, and he had a stick under the seat, and soon as he’d get out, he’d say, ‘Christopher, pass me my headache stick.’ And I’d pass him his headache stick. A couple of times, we actually ended up in fights. And the headache stick was great, it could do anything, you know? Sometimes, like, the car would break down. He’d be like, ‘Pass me my headache stick.’ And he’d hit the engine a couple of times, and the car would start.”

It is hard to capture accurately on the page just how animated and happy Chris seemed when sharing his recollections about his grandfather. It was a privilege for me just to listen to him. And I could easily see how Chris’s comedy had grown out of his affection for a man like this. Unfortunately, our efforts to trace Chris’s paternal ancestors past the births of Allen and Mary Rock yielded a series of names but no real stories that could suggest where the strong personalities and strong sense of humor came from. We found records tracing the family back generations to early-nineteenth-century South Carolina, but few anecdotes.

Turning to his mother’s side of the family, however, we were much more fortunate in our research. Chris’s maternal grandparents were Wesley Tingman and Pearl McClam. Both were born near Andrews, South Carolina—Wesley on October 6, 1915, and Pearl on July 25, 1911. Chris had known both of them growing up and remembered them fondly, but he knew little about their parents and grandparents. “My family never sat around and talked about ancestors,” he said, echoing the sentiments of almost everyone involved in this project. “We’d talk about aunts or an uncle or a grandpa, but that’s about as far as we got.”

Our research revealed that Chris’s grandfather Wesley was the son of James Tingman, born in January 1886 in Berkeley County, South Carolina, and a woman named Emma Telefair, who was born in 1890 in the same county. Going back a generation further, we were able to identify James Tingman’s parents—Chris’s great-great-grandparents—Eliza Moultrie and Julius Caesar Tingman. Both were born into slavery in South Carolina, Julius in 1845 and Eliza sometime around 1850.

Chris was astonished to hear that Julius Tingman served in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War, enrolling on March 7, 1865, just a little over a month after the Confederates evacuated Charleston. At that time South Carolina was filled with Union troops, and the newly freed slaves were enlisting in droves—over two hundred black men were signing up each day. Chris’s great-great-grandfather Julius had just become free after twenty-one years living as a slave. Signing up to serve in the U.S. Colored Troops must have been one of the first things he did as a free man. He could have fled to the North or stayed in the South and attempted to make a new life as a farmer, but he risked his life by joining the army and fighting for the freedom of other slaves.

“I can’t imagine what making a decision like that would be like,” said Chris. “I’m very fortunate. I’ve never been in any kind of situation like that.”

We discovered that Julius Caesar Tingman, Chris’s great-great-grandfather, was elected to the South Carolina state legislature—a revelation that nearly brought Chris to tears.

Chris was moved to tears when he saw Julius Tingman’s service records. And together, we parsed them closely, looking for details about the man. The records indicated that Julius was a blacksmith, which means he was most likely quite physically strong. They also indicate that he was promoted from private to corporal within four months after he joined the army, which means he must have been a successful soldier.

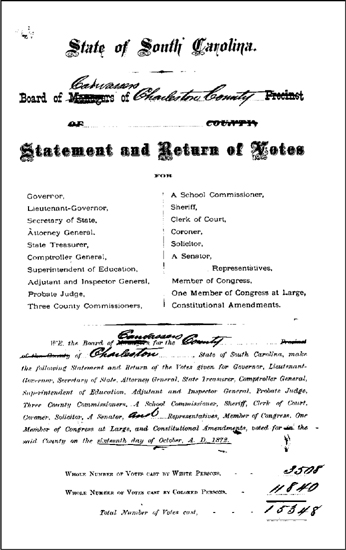

But the most remarkable aspects of Julius’s biography all concern what he did after he left the service in October of 1866. At that point Julius entered a world so far removed from the life of a field hand that one scarcely knows how he could even have imagined it, much less navigated it. South Carolina during the heyday of Reconstruction was a state with an overwhelmingly black majority, enjoying its first days of freedom. More than 60 percent of the population was black, and these new citizens were eager to make the most of their new rights. Chris’s great-great-grandfather must have thrived among them, because in 1872, when he was just twenty-four years old, Julius Caesar Tingman was elected to the South Carolina state legislature.

As I explained to Chris, Julius was in the right place at the right time. The South Carolina constitution of 1868 was an exceptionally progressive document. Not only did it give African American men the right to vote, it also removed the property qualifications for holding office. In many other states, no man—white or black—could vote unless he owned property. But Reconstruction South Carolina extended the ballot to all men, regardless of their station in life.

How did Julius get elected to the legislature? We are not certain. He was a former slave with no property to speak of, but census data indicate that he was a literate man and had served honorably in the army. That combination was probably a big part of his candidacy. He was also, most likely, very articulate—like a preacher or a comedian—as he had to convince his fellow citizens to vote for him.

“This makes me feel really proud,” said Chris, showing me a side of himself that I had never encountered before. “It’s weird. There’s a part of me that walks around thinking I’m so lucky. And I am lucky to have grown up where I grew up and end up where I am now. There’s a million reasons why I’m lucky. But when you see stuff like this you go, ‘Oh, okay, some of it wasn’t luck.’ Some of it was, sure, but maybe I was actually born to do certain things, you know? I had no idea, but still, if you didn’t know Ken Griffey was your dad, you’d probably still play baseball pretty good, right?”

As I told Chris, there was a lot more to Julius Tingman’s story. We looked at records of the South Carolina House of Representatives to find out what Julius Caesar Tingman did as a legislator. It turns out that he was an active legislator. He introduced bills attempting to protect the rights of former slaves who had become sharecroppers, as well as bills to protect turpentine workers from unfair price setting and to regulate the conditions for tenant farmers. Not all of these bills passed, but he obviously had a strong sense of social justice—and he clearly worked very hard. He was concerned with the rights of the common man, the workers and the sharecroppers—the former slaves—he grew up with.

“It’s unbelievable,” said Chris, “and it’s sad that all this stuff was kind of buried and that I went through a whole childhood and, you know, most of my adulthood not knowing. I mean, how in the world could I not know this?”

Chris has such a noble ancestor in his family. Julius Tingman’s picture should have been over the mantelpiece in his descendants’ homes. Each successive generation should have been told this man’s story. Chris should have known he came from people, as my mother’s expression goes. But he didn’t. And this, I have found, is remarkably common among African Americans. It is as if we have amnesia, not just about our collective history but also about our individual family history—as if the racism of America in the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century was so painful that we should forget everything that occurred in those years. Indeed, no one I interviewed for this project knew anything about the deep roots of their family trees. A wealth of history and accomplishment has simply been forgotten, which it is incumbent upon our generation of journalists and creative writers and academics to resurrect—so that it will never be lost again.

“It’s messed up” said Chris after a moment’s reflection. “I was raised in a neighborhood where no one went to college or anything. And I just lucked into a comedy club at age twenty, you know, just on a whim. Up till then I assumed I would pick up things for white people for the rest of my life. Because that’s what everyone I knew did. They picked up and cleaned and moved for white people. That was my world, you know? And when I worked in restaurants and whatever, it wasn’t like I was working my way through to become a comedian. That was what I thought I’d be doing with my life. But if I’d have known this Julius, it might have taken away the inevitability that I was going to be nothing. And I might not have been a comedian. I might have worked harder in school. I might have been a civil-rights lawyer. Or I don’t know what. And it’s not just me, you know. Other people in my family would have benefited from knowing that they had this kind of ancestor. You know about a guy like this, it’s like that’ll make you take school serious.”

I understand Chris completely. The memory of this man Julius has been lost to his descendants and to the African American community. There are thousands of Julius Tingmans. And we pay the price, collectively, for that loss. We pay it every day. There are so many people like Julius Caesar Tingman waiting there to be rediscovered, examples of black achievement trapped in the amber of the archives. The records of Chris’s ancestor were just sitting in a courthouse in the archives of the city of Charleston, South Carolina, waiting to be rediscovered. Think what else is out there, if we only search.

What’s more, Julius’s story doesn’t end here. After serving in the South Carolina state legislature from 1872 to 1874, he ran for office again in 1876—and his experience in that election is reflective of the tragic betrayal of Reconstruction.

A lot changed in the four years between 1872 and 1876. Disgruntled former Confederates who wanted to regain control of the South were doing so, state by state. The 1876 election had a dreadful result for black people all across the nation. In South Carolina the Republican Party, which in those days was the party of progress—the party of Lincoln—ran a ticket headed by the incumbent governor, Daniel Chamberlain, a friend to African Americans. In opposition the Democrats ran a ticket headed by Wade Hampton, a former Confederate general and war hero—and a leading critic of Reconstruction. The elections were tainted by irregular practices on both sides. There was violence in the streets, with armed clashes between whites who supported Hampton and blacks who supported Chamberlain. In the end Hampton claimed to have won more votes, but Chamberlain refused to concede, and South Carolina actually had two competing state governments for more than six months. And just as there were two competing governors, there were two competing speakers of the house of the state legislature; each with his own posse of legislators. It was utter chaos, and Julius Tingman was in the middle of it, serving in the Republican legislature and supporting Chamberlain.

In 1877 the newly elected president of the United States, Rutherford B. Hayes, pulled all the federal troops out of the South. Without the support of these troops, Chamberlain had to concede the governorship to Hampton. The ex-Confederate had won. Reconstruction was over in South Carolina—and indeed all over the South. Hampton and his supporters in Charleston acted quickly. Julius Tingman and all his fellow Republican legislators were kicked out of office with the backing of the South Carolina supreme court. Soon thereafter African Americans were effectively disenfranchised by the new legislature. The last black representative left office in 1902, and there would not be another black man elected in South Carolina again until 1970. The “redeemed” former Confederates cleaned Reconstruction’s house.

So what happened to Julius Caesar Tingman at this point? He was still a young man when Reconstruction ended, only thirty-two years old. And he clearly had a lot of energy, imagination, and intelligence. But, of course, in 1877, South Carolina was not interested in young black men with these qualities. We found Julius in the 1880 census listed as a tenant farmer, renting ten acres of land from a white man. He owned three cows and grew rice and sweet potatoes. In fifteen years he had gone from being a slave to a soldier to a legislator, and now back to the soil, in another form of servitude, to a life as a hardscrabble farmer.

“What a roller-coaster ride,” said Chris, shaking his head. “That is sobering. I mean, he was the man, right? And then these racists come in, kick him out. What’s he going to do?”

Chris is right. Julius had very few options. And the ups and downs of his life give us a sense of what it was like to be black in America a century and a third ago. Success, measured by most standards, was quite perilous for a very long time in the lives of the former slaves, especially in the fragile period of massive black vulnerability between the end of Reconstruction in 1876 through the enshrinement of “separate but equal” as the law of the land in 1896. What a hellish twenty years for black people in this country, but especially those in the South. Julius Tingman’s rise and fall serves as a metaphor for this fragility of black success, and his turn of fortune had absolutely nothing to do with anything over which he had control.

“I wonder what kind of guy he was,” said Chris, realizing all the implications of encountering a family member for the very first time, as if your mother or father had had a child or a sibling long lost but now found. So many stories about our ancestors in the nineteenth century have similarly sad endings. But not, fortunately, the story of Julius Tingman. The answer to Chris’s question about what kind of person his ancestor was could be found right there in the historical records. Julius Tingman was a determined guy, an incredibly determined guy. Nothing was going to keep him down. Tenant farming was a most brutal way to earn a living in the Jim Crow South, but Julius found a way to make it work, and to great profit, though Lord knows how. We located a land deed from 1904 that reads, in part, “W. A. Spears of Berkeley County in consideration of $168 sold and released onto the said Julius Caesar Tingman a parcel or lot of land in the parish of St. Stevens county of Berkeley, 21 acres more or less.”

This means that by the age of fifty-six, after working his rented land for twenty-five years, Julius had saved up enough money to buy his own farm. What’s more, when the former state legislator died thirteen years later, his will indicates that he owned sixty-five and a half acres and two life-insurance policies. Even though he had no resources when he was kicked out of the legislature in 1876, Julius Tingman still managed over the next thirty years to find a way to provide for his family. He died an extraordinarily successful man, a man wealthy by comparison with his peers.

“I’m very proud of him,” said Chris. “I mean, he’s a great man. Most people would have given up. And, you know, my family’s main attribute has always been hardworking people. I mean, when there is a lazy family member there is, like, an intervention. We treat it like it’s drugs. Like, ‘Oh, God, what the hell is wrong with you?’ So it’s nice to know that some of this work ethic actually went back to slavery—that’s unbelievable.”

I was extremely happy for Chris. The story of Julius Tingman is one of the most inspiring stories that I uncovered in this entire project. Unfortunately, it is also a very singular story within Chris’s family. Our additional research into his other maternal ancestors was nearly as fruitless as our work on his paternal side—as almost every line ran into dead ends in that mysteriously dark mausoleum called slavery. We learned, for example, that one of Chris’s other maternal great-great-grandfathers was a man named Alex McClam. He was born a slave in South Carolina in about 1837. We found his name on a militia enrollment list from Williamsburg County, South Carolina, taken in 1869, just four years after the Civil War. On the list Alex declares that he was living on the property of a white landowner named Solomon McClam. This, of course, led us to believe that Alex had been the slave of Solomon or his family—because, as we have seen in a surprising number of examples, in the years after the Civil War it was common for freed slaves to remain on the property of their former owner as sharecroppers or tenant farmers. We then began searching McClam’s records, and we found a slave schedule from the 1860 census that lists a male slave age twelve—which is roughly how old Alex McClam would have been at that time. So it seems highly likely that Alex was in fact Solomon’s slave and that he took his former master’s name after gaining his freedom. But though we scoured the rest of Solomon McClam’s records, looking for any reference to Alex or his relatives, we could not find any other clues. And, indeed, Alex was the only one of Chris’s ancestors for whom we could identify a possible slave owner.

I explained to Chris that, unfortunately, this is pretty normal for African Americans. All African Americans hit a genealogical brick wall somewhere in slavery. Slavery was constructed to deconstruct the Negro, in every way imaginable, except as pure labor, as a measurable commodity.

“Wow,” said Chris after a pause. “It’s amazing no one’s ever been persecuted for treating people like this—taking away their names, taking away everything. And people just treat it like essentially it’s a fact. Like disco—or bell-bottoms. It’s just something that happened. Slavery. You know? I’m just choked up.”

I can sympathize with Chris, of course. There is nothing that upsets me more than the way our ancestors were treated. Nothing is more horrifying, more outrageous, more unjust. And seeing it all written down in these cold, clear documents from a century and a half ago can be terribly sad, even if the thrill of discovering such documents is a rare pleasure scarcely to be described.

I wanted to be able to soothe Chris by telling him more about his family, but I had little to say. The furthest back that we could trace his surname, Rock, was to his great-great-grandfather Josiah Rock, born a slave in 1830 in South Carolina. But we know nothing else about him—or about the source of Chris’s surname. There was a famous black abolitionist called John Rock, but we could find no connection between the two families. Nor could we find anyone named Rock who owned slaves who might have been Chris’s ancestors. We spoke with researchers who specialize in African American genealogy in the Low Country in South Carolina, and they told us that in their experience fewer than 20 percent of the former slaves in this area took their surnames from their previous owners. We don’t know why that is. The practice of naming simply varied from county to county and state to state and, indeed, from former slave to former slave. We did find a number of slaveholders of French Huguenot origin named La Roche in this area—and, if anglicized, “La Roche” would be “Rock.” But none of these people had slaves we could identify as being Chris’s ancestors.

At this point we turned to the DNA portion of our research. Chris’s admixture tests reveal that he is 80 percent sub-Saharan African and 20 percent European. He seemed very comfortable with this result.

“You have to assume that any black person has some European ancestry,” he said, waving his hand before his face. “And, you know, just the fact that I am not blue-black—I’m a mocha. I knew there’s something else in there. I heard stories in my family, stories about Indian ancestry. But I guess they were wrong.”

This, as we’ve seen, is quite common in African American families. Virtually every black person has some white ancestry. Yet so many black people believe they have Native Americans in their family trees.

“It’s all about that hair issue,” said Chris. “It goes all the way back to the hair issue, and anybody with the so-called good hair, you know, it’s easier to say we got a little Indian in us than to say we got raped a few times. It’s just a lot easier to say. You make up a myth, sounds much better, a lot smoother.”

I asked Chris if it mattered to him how his European ancestors entered his family tree. He shook his head in response.

“The Africans didn’t have a choice,” he said. “I’m not going to ever say it’s by love, you know what I mean? But it doesn’t bother me like that. I guess I’m used to it. I mean, you know, you’re black so you assume you’re whatever, there is some white in you. That was a horrible thing to say but it’s true.”

Before telling Chris what his DNA had told us about his African ancestry, I wanted to know what his impressions of Africa were. Like many of the people involved in this project, he rarely spoke about Africa with his parents or thought about it much growing up—but as an adult and an international celebrity, he has traveled throughout South Africa extensively.

“I was forty, and I went to South Africa,” he said. “I went on safari. I went to Mandela’s house and sat with the great man. And then to Robben Island. Unbelievable. Just being on safari was kind of like being underwater and able to breathe without an apparatus. There’s that much nature around you. It’s like meeting God. But, you know, I also saw some of the worst poverty I’ve ever seen in my life. Incredible. We can’t even imagine it in this country.”

I ask him if he felt a deep connection to Africa, and he shook his head.

“No,” he said. “A little bit, but not a deep one. You know, I did a joke in my act. It’s, like, I sat with Mandela, and, you know, what do you talk about? He’s eighty, I’m forty. He’s a Rhodes scholar. I dropped out of school. He was in jail for twenty-seven years. I worked at Red Lobster for eight months. So I have so much more in common with Pauly Shore than with Nelson Mandela. That’s just the way the world is. But yet we are brothers of the same skin. I am an American person whose ancestors hailed from Africa. And I have African blood flowing through my veins. I know that.”

I think Chris’s answer here reflects a sentiment that many of the people I interviewed for this project have shared—they are uncertain, at some deep level, as to what their connection to Africa means. I know that I feel the same way—even though I adore Africa and cherish every moment I’ve spent there. At the most basic level, we are Americans, after all, and it is hard to reconcile the two continents and the tragic history that has passed between them, to reconcile our being descended from Africans in America with Africans who remained on the African continent. I had hoped, in launching this project, to help make that connection through DNA. I am not certain, however, how well it worked. It is very difficult, I think, to go from test data to an emotional connection. Chris was an especially interesting subject in this regard, because his results were not precise, yet he clearly wished to make the deeper connection that I believe we all crave.

Our African admixture test revealed that just under 25 percent of Chris’s African ancestors come from Congo Angola, about a third come from western Nigeria and the country of Benin, and 45 percent come from the region that stretches from Liberia all the way up to Senegal. So Chris is a real reflection of our shared history. In the New World, slaves from different groups were thrown together on plantations where they formed new family bonds and interbred with one another. And his African genetic ancestry reflects that.

Chris’s mitochondrial DNA test results are similarly diverse. Many of the people we tested for this project had exact matches with their mitochondrial DNA, tying them to one or two tribes in Africa. Chris does not have that. He has matches all over the African continent, many of them only partial matches. And given the amount of time it has taken for the human genetic code to spread across Africa, it was impossible for the historians John Thornton and Linda Heywood to tell me which group Chris’s ancestors on his mother’s side come from. They could be from any of a number of tribes in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Angola, or elsewhere.

I told Chris this meant he had a very ancient genetic signature and that his ancestors had intermingled across Africa perhaps since the time of the first humans. We’ve never had a result like this. He is the most pan-African person we tested—at least on his mother’s line.

Chris seemed somewhat confused by this news. Undoubtedly, he had hoped for more, and I was glad, therefore, to be able to tell him that his Y-DNA yielded something truly concrete: an exact match with the Uldeme people from northern Cameroon.

“Ah, man,” said Chris, almost shouting, “that feels complete! You know, that feels great. This was worth getting up early!”

He seemed visibly relieved and truly excited and told me he plans on making a trip to Cameroon as soon as possible. I asked if now he felt that he had that connection we discussed earlier.

“I don’t know yet,” he replied, shaking my hand and laughing. “You know? It’s one of those things we’ll see in the coming year and we’ll see maybe in my work. I’m curious. I want to see if it rears its head in the work. I remember before I did my last special, for some weird reason I watched Roots, like, a week before I did it, and I ended up with all these big, long pieces where I was, you know, playing slaves. So we’ll see.”

Mostly, he told me as we said good-bye, he was ecstatic to have this news for his children—so that he can, as he said, “start drilling this in their heads.” And I understand him. In fact, I think this may be the true purpose of this entire project. I am not certain, not at all, that my peers and I can fully understand the results of these tests. The science is just not fully there yet—but neither are we, emotionally speaking, fully ready to understand our relationship to Africa. We grew up in a maelstrom, amid history that is still unresolved. I hope that restoring the knowledge of our ancestry, on both sides of the Atlantic, can give us new perspectives on the history of our family tree from its roots in Africa to its myriad branches in the New World.