6

We’re off to Vietnam

Terrie Ross née Roche, RAANC

8th Field Ambulance, May 1967–March 1968

1st Australian Field Hospital, April–May 1968

Platoon Sergeant Alexander ‘Jock’ Sutherland had been directly hit by rocket fire on a search and destroy patrol during the Battle of Suoi Chau Pha. His left side had taken the brunt of the attack, leaving his lower leg, his arm and his eye all badly damaged. Six Australians had been killed in the battle and another twenty, including Jock, were wounded. By the time he was winched out of the jungle by the dustoff crew, it looked like Jock might push the first number up to seven. It was 6 August 1967.

Sister Terrie Roche was on duty in the intensive care unit at the 8th Australian Field Ambulance when Jock was wheeled in after several hours of emergency surgery. His left leg had been amputated, his left arm was swathed in bandages and his left eye was gone. She remembers him well all these years later. ‘He was so sick,’ she drawls in a voice made gravelly by years of soul-soothing nicotine.

Terrie kept a close watch on the wounded soldier and did what she could to make him comfortable. Hours later, however, as she was due to go off duty, she was still trying to get him to close his other eye and rest. ‘You’ve got to have a bit of a sleep,’ she said. ‘You need to rest. Close your eye and go to sleep.’

It took some time, but Jock finally admitted that he was afraid to go to sleep because he thought he’d never wake up. Terrie assured him he would: ‘I promise you’ll feel better after some sleep and I promise you, you won’t die.’

‘Well, I’ll go to sleep,’ he said, ‘if you’ll stay with me.’

‘You’re on!’ she said, mentally cancelling the date she was meant to be going on.

Terrie sat beside Jock for hours, all through that first reprieve. When Jock woke up, he knew he’d survive.

Terrie Roche grew up in Goulburn in country NSW and completed her general training at the Goulburn Base Hospital before moving to Sydney, where she trained as a midwife at St Margaret’s Hospital in Darlinghurst. When she finished she went back to Goulburn, ‘just for a month’. She’d been there almost a year, living at home very comfortably with her parents, when she came in one day and said to her mother, ‘I think I’ll buy a car.’

Gazing at her indulgently, her mother replied, ‘You don’t need a car. Your father’s is there; you can use that.’

Terrie might never have left the maternity wards of the Goulburn hospital if a darling old nurse called Nora Marmont hadn’t told her that she had to go. Terrie knew that Marmie had been a nurse on a hospital train in Japan during the Korean War. She also knew that Marmie had spent her life looking after her brother’s children after he lost his leg, then her parents as they had aged. Last of all, Terrie knew she worked permanent night duty.

Ever the joker, Terrie asked her, ‘Don’t you like me, Marmie?’

Marmie eyeballed her and replied, ‘I do like you, young Terrie. That’s why I want you to leave. If you don’t, you’ll end up here with your fifth baby and you’ll have been nowhere and seen nothing!’

‘Cripes,’ said Terrie. ‘What am I going to do, then?’

‘Go join the army,’ said Marmie.

Terrie went home at the end of her shift and said to her mother, ‘I think I’ll join the army.’

Quick as flash, her mother suggested, ‘Why don’t you buy a car?’

Terrie enlisted in the army at the age of twenty-three with little real nursing experience but plenty of enthusiasm. After her interview and acceptance by the matron-in-chief of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps, just like the soldiers, Terrie had to pass a medical examination before she got the final tick of approval. Unlike the soldiers, she had to shop around for the ‘delicates’ on her required clothing list. In spite of the fact that nurses had been serving with Australian troops since the Boer War in South Africa at the turn of the twentieth century, the army clearly still wasn’t used to women being enlisted. When Terrie went to collect her uniforms at the quartermaster’s store – or Q store – which provided most things required by military personnel, she was given a chit and instructions to go to David Jones to buy appropriate underwear. Once that was sorted, and with the automatic officer rank given to all nurses in the military, Lieutenant Terrie Ross headed off to join the staff at the No 2 Military Hospital at Ingleburn outside Sydney. It was May 1965.

The Australian Army Training Team Vietnam had been on the ground in Vietnam since 1962 and the first Australian death had occurred in 1963 when Sergeant William Hacking of the AATTV was accidentally killed. The first combat death occurred a year later when Warrant Officer Kevin Conway of the AATTV was killed in action at Nam Dong. By August 1964, the first RAAF transport unit was deployed to Vietnam and, three months later, the Australian government passed the National Service Act. The first national service conscription ballot was drawn in early 1965, a couple of months before Terrie enlisted. As she was learning the ropes at Ingleburn, the first national service recruits were arriving at Singleton Army Base about 200 kilometres north of Sydney, and the first troops from the 1st Royal Australian Regiment (1 RAR) arrived in Vietnam ready for deployment to Bien Hoa. Around the same time, RAAF Squadron Officer Harriet Fenwick flew from Butterworth RAAF Base in Malaysia to Bien Hoa to prepare Aussie casualties for the first medivac flight back to the No 4 Hospital at Butterworth and then home to Australia.

Terrie spent twelve months at Ingleburn, during which time she went to the Healesville School of Army Health for some basic training. She didn’t learn anything particularly useful there, but she did gain a lot of good practical nursing experience at Ingleburn. When she was transferred to Singleton, where the recruit numbers were ramping up, she was quite reluctant to go; of course, she had no choice in the matter. The army had already opened Singleton to recruits when they realised they didn’t have a hospital there, so they commandeered the Red Cross hut. If there were more patients than beds available in that building, the nurses would tuck the necessary documentation under their arm, grab a pile of medical supplies and go visit the troops in their own huts. Much to her astonishment, Terrie found she really enjoyed it. She was struck by the enthusiasm of the young national servicemen, who all seemed to love being in the army. ‘They were all so young,’ she recalls. ‘A bit like our younger brothers.’

A boy came to see her one day in floods of tears. Terrie asked him what was wrong. He told her he’d never been away from home before and how much he liked all the new things he’d learnt and all the new people he’d met but, ‘after all that, they want to send me home’. Terrie assumed he’d missed out on some qualification or other and was so incensed on his behalf, she went up to HQ and told them that it wasn’t right and that she was going to ring the radio station and say ‘they plucked this boy out of his home, stuck him in the army where he’s as happy as a bird and now they want to send him home’. Laughing at the memory, she says, ‘They told me, “Go back to work, Sister Sympathy,” and sent him home anyway. My word had absolutely no impact whatsoever!’

Meanwhile, over in Vietnam, the 2nd Field Ambulance was established in March 1966 at Vung Tau to support the Australian forces already in-country. A year later, it was replaced by the 8th Field Ambulance, staffed by doctors and medics who provided medical services to the Australian Logistic Support Group at Vung Tau. The 8 Fd Amb also had a satellite unit at Nui Dat. However, as the Australian government’s commitment to the war accelerated, the increasing number of Aussie casualties and multiple-casualty medivacs such as those that followed the Battle of Long Tan demonstrated the need for expanded medical facilities. The army responded by deploying the first four officers from the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps to the 8 Fd Amb at Vung Tau.

When Terrie was advised that she was being posted to Vietnam, she was very keen to go but surprised at how sad she was to be leaving Singleton given her initial reluctance to go there. The team of four – Captain Amy Pittendreigh, Lieutenant Margaret Ahern, Lieutenant Colleen Mealy and Lieutenant Terrie Roche – was sworn to secrecy, banned from telling anyone anything at all. With just a few weeks to prepare, the nurses had all their vaccinations, medical and dental checks and organised their passports and visas without giving away a hint of what was happening. Needless to say, Terrie was as shocked as her parents when they heard on the radio that she was going to Vietnam.

There was, in fact, quite a lot of fanfare about their departure as various journalists interviewed and photographed them for their print publications and radio shows. It was all excellent publicity for the army and presumably reassuring for the families of the boys who’d been called up in the national service ballot and tagged for deployment to the war zone.

They flew into Saigon, via Manila in the Philippines, in May 1967, on a ‘Skippy’ – a Qantas V-Jet contracted to fly troops in and out of Vietnam. The pilots and hostesses were some of many who volunteered to crew these planes and were ‘just lovely’, Terrie recalls. ‘They invited us nurses up into the cockpit to have a good look around.’

Even though Terrie was excited to be on her way, she was also quite nervous. ‘I didn’t really have that much experience and certainly none that was relevant to the war. You didn’t look after malaria or bomb injuries or people with shrapnel wounds back in the wards at home.’ In fact, none of the nurses had any preparation for going into a war zone and no idea what to expect. There were several surprises awaiting them, not least the oppressive heat.

When they walked down the steps of the plane at Tan Son Nhut airport in Saigon, in their starched grey uniforms, grey hats and seamed stockings with black shoes, gloves and handbags, all four nurses were stunned by the blanket of heat. ‘I thought it must be from the jets as we walked off, but it was just as hot inside the terminal,’ Terrie explains.

Once they had negotiated customs, the four nurses flew the last leg of their trip ‘on the Wallaby’, the nickname coined for the RAAF Caribous that flew supplies around the American bases as well as Australian personnel between Saigon and Vung Tau. Strapped into seats along the walls of the big belly of the aircraft and rendered speechless by the roaring echo of the engines, the nurses contemplated the months ahead.

Disembarking in Vung Tau, they walked into another wall of unbelievable heat. Drawing the words out with a rumble of mirth, Terrie says, ‘It was a very even temperature, though; just very, very hot all of the time. It took us a couple of weeks to get used to it, especially wearing nylon stockings!’

One of the 8 Fd Amb doctors met them at the airstrip and ferried them all back to the ALSG compound at Back Beach on the eastern side of Vung Tau, which sits at the tip of a peninsula jutting into the South China Sea. Having driven through the shanties on the outskirts, the nurses were surprised to see that in town French villas predominated, especially along the ocean esplanade. The road to Back Beach, on the other hand, was notable for the presence of a large rubbish tip and an old French fort.

The compound was quite stark and the nurses’ quarters very basic, although they were, at least, timber rather than the canvas tents accommodating most of the military personnel. The walls were only shoulder high and there were no ceilings in the rooms, but they did have cement floors. There were no air conditioners or fans to relieve the heat and the low walls were no protection from the sand that blew through everything, especially in the dry season. The nurses were pleased to discover, however, that they had their own sitting room, which afforded them a communal gathering place other than the officers’ mess.

Each of the bedrooms had a small cupboard, a dressing table and a stretcher bed. The mattresses weren’t chosen for softness but none of the nurses cared; certainly not Terrie, who says, ‘We had a lot of fun in those early days and we were well looked after by our wonderful Vietnamese housekeeper who we called Mamma-san. She couldn’t speak English and we couldn’t speak Vietnamese, but somehow we managed with a bit of pidgin and a kind of numerical code we made up. She was fascinated by everything about us and I remember her laughing as she watched me shave my legs. She’d grab the hair on my arms as if to say, “What about this?” Mamma-san did everything for us, so I never thought about things like sheets. I just rolled into the bed when I needed to.’

A canvas fence surrounded the nurses’ quarters to maintain some semblance of privacy. Inside the fence, the nurses had their own ablution block with cold showers and long-drop toilets (a toilet seat fitted onto a bench over a very deep hole in the ground). Terrie might not have worried too much about their accommodation, but she did worry about the cold showers. She hated them. As the nurses got to know everyone, it came to the attention of the Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers field workshop that the nurses didn’t have hot water; shortly thereafter, the RAEME guys built them a hot water contrivance called the ‘choofer’ to make their lives a bit more comfortable. During that year, Terrie became good mates with the adjutant of the RAEME unit, Mick Ross; they had a lot of laughs when they could find something to laugh about.

The 8 Fd Amb was an equally rustic complex. The building itself was shed-like, with columns of louvred glass windows around the outsides of the two wards, one medical and one surgical. In between the wards there was a paved path that became a covered walkway leading out past the operating theatre and an eight-bed ICU to Vampire, the helicopter pad, which was marked by a big cross for the dustoff choppers to land on. The theatre had two operating tables and doubled as triage while they sorted out who needed surgery first. The only air-conditioning was in the theatre and ICU; the wards reflected the temperature outside, making it challenging to manage high fevers.

Until the nurses arrived, the 8 Fd Amb doctors were assisted by army medics, most of whom had little or no medical experience until they were posted into the medical corps – although one did tell Terrie he’d been a porter at Concord Hospital in Sydney. There were no appropriate storage spaces and the medications were all dumped in a pile on a table at one end of the wards, with no proper documentation about who took what or when.

The nurses were horrified, but soon had the medics building shelves and cupboards and learning about documentation and routines. It took a little while for some of the medics to get their heads around taking direction from the nurses, but Terrie swears that the ones working for her were wonderful, adding, ‘I had the best sergeant and best corporal working for me. We’d been there a few months when one of them was going to Nui Dat and the other was having a birthday, so I said, “We’d better go out.”’

Normally officers would never mix socially with the lower ranks, let alone have celebratory drinks, but off they all went to the Badcoe Club at the beach. Terrie had a fine time and several drinks. Next morning when she arrived at work, the sergeant was there even though he was supposed to be off duty. Terrie said to him, ‘You’re not rostered on today. Why are you here?’

‘I got my shifts wrong, Sis,’ he said. ‘I’m just going.’

After he’d left, the corporal sidled up to Terrie and explained, ‘He didn’t think you’d make it, so he was going to cover for you.’

Thinking about the medics all these years later, Terrie says, ‘You know, they looked out for us and they were so respectful of all of us. They always called us Sister or Sis, never by our first names, and they never ever swore in front of us, although we’d sometimes hear a bit of shushing!’

Captain Amy Pittendreigh was in charge of the nursing officers and was, Terrie says, a wonderful nurse who worked on the wards when needed. ‘She was brilliant at negotiating with the hierarchy. She was a very capable country girl from Western Australia who was never flustered or upset about anything.’ Shortly after they arrived, a New Zealand army nurse, Margaret Torrey, joined them.

The five nurses all worked ten-hour shifts, six days a week, overlapping so that at least one nursing officer was on duty at all times. Terrie ran ICU, but all of the nurses with the exception of the theatre sister would also roam where they were needed. ‘We’d work shifts so that there was always a nurse available to the medics if they needed help or direction.’ Sometimes the nurses worked a split shift from 7 a.m. to midday and then 5 p.m. until 10 p.m. just to make sure that everything happened as it was meant to, although it was quickly obvious that it was the medics who made the hospital cogs run smoothly.

One day soon after they arrived, Terrie was looking for a pair of scissors to cut off a bandage. When she couldn’t find any she went to theatre and asked if she could borrow some. As she had to be, the theatre sister was particularly careful about accounting for every instrument and said, ‘No, sorry. Nothing goes out of this theatre.’ Terrie went back to the ward, where one of her medics asked her what the problem was.

‘Well, Sergeant, I can’t find any scissors so we’re going to have to chew this bandage off.’

‘If you want scissors, Sis, I’ll get you scissors,’ he said. He went off to see one of his medic mates and came back with a pair of scissors.

‘Any time you want anything, Sis, you just ask me.’

Terrie did, and somehow he always found whatever she needed.

As the pace of the war picked up and more casualties arrived, the 8 Fd Amb’s capacity to respond reflected the capabilities of the nursing officers, though it was limited by the number of beds they had: ten down each side of the medical and surgical wards, eight in ICU and a few in another room for the patients with venereal disease (who weren’t actually sick but were kept there to make sure they got their full course of antibiotics).

The facility was now better organised and time-managed, thanks to the nurses, and better resourced, thanks to the generosity of the Americans, who were encouraging everyone they could think of to get involved in the Vietnam conflict and warmly welcomed the contribution Australia made. Terrie reckons they could get hold of anything from a tin of baked beans to a diamond ring over at the American PX store, and often did. ‘And,’ she says, ‘you could swap just about anything for a slouch hat; even a two-ton truck.’ It seems the Americans were fascinated by all things Australian, including their accent and funny language. With an amused look, Terrie adds, ‘They used to laugh every time they heard Amy’s name and where she came from. She was Amy Pittendreigh [pitten-dray] from Manjimup!’

The Americans’ generosity extended to medical support. If more casualties came in than they could handle at the 8 Fd Amb, the most critical would be sent over to the nearby US 36th Evacuation Hospital. In fact, there were some really critically injured patients who went straight to the 36 Evac Hosp anyway to take advantage of the Americans’ superior facility and resources.

In the ICU, Terrie mostly looked after surgical patients, who would usually stay for a few days until they could go to the surgical ward. The critical patients stayed in ICU until the next medivac flight home. At this stage of the war the RAAF was flying in every two weeks to evacuate whoever needed to return to Australia. The nurses on duty would spend the day before the plane was due preparing their patients for the flight and then, when the ambulances arrived with the RAAF nurse to take them back to the plane, the 8 Fd Amb staff would all line up to farewell them as they were carried down the walkway to the waiting vehicles. Usually, they never saw or heard of any of them again.

There was one happy exception for Terrie, however. Many years after she watched over Jock Sutherland as he slept, she was delighted to learn that he had indeed survived. She knew he’d made it home because he’d written and told her so, but then she never heard from him again. Years later Jock’s wife, Mindy, went to Woden Hospital where Terrie was working and thanked her for caring for him. When Terrie told her that Jock had written her a letter telling her about his trip home, Mindy was surprised; she told Terrie she’d never seen him put pen to paper ever. She reckoned it was probably the only letter he’d ever written. Terrie gave her a copy and the two women have remained in touch, connected in ways that only their fellow veterans and their families could possibly understand.

As hardworking and professional as the nurses were, they were still young women who liked to dress up and party when they got the chance. Although they wore civvies off duty around the ALSG, when they went out in a chopper, as one of them did each week to run a clinic at a nearby village, or when they went socialising, as they did very occasionally up at Nui Dat, they wore the jungle greens (pants, shirts and caps) they’d been issued but never wore in the hospital. The first time a few of them, including Terrie, turned up in their greens to go to Nui Dat for a barbeque the accompanying soldiers booed them onto the Iroquois. The boys much preferred seeing them in the starched grey dress uniforms and stiff white veils they wore to work each day, even if they weren’t very practical for climbing in and out of a chopper.

A tall, pretty, soft-hearted young woman with short dark hair and liquid brown eyes, Terrie had a penchant for wearing lipstick and perfume. Many of the nurses did as it brightened their spirits. It turned out it brightened the spirits of their patients as well. A soldier came in on the dustoff chopper one day and declared he knew he was safe because he could smell perfume. In the years that followed, it became common practice for the nurses to carry perfume in their pockets so that when the dustoff siren went, they could splash a bit on; the boys would know they’d made it to the hospital even if they couldn’t properly see.

The soldiers were cranky with Terrie, however, when she insisted on putting lipstick on a Viet Cong woman they were nursing at the hospital. ‘I used to put some lippie on her and give her a cigarette. I knew she was the enemy but I used to think if I was in the same boat, I’d want someone to do the same for me.’

They didn’t see a lot of Viet Cong, but there was one little fellow whom they looked after for months. Mot was about seven or eight years old; they couldn’t be certain because he was very small. He’d been ‘captured’ when his parents were killed carrying ammunition for the Viet Cong. When he was brought in to the hospital, Mot was filthy and very ill; he was weak and obviously anaemic. They found he was riddled with worms and suffering from malaria. The doctors ordered a transfusion and antibiotics for him and he was put to bed in the medical ward. He eventually recovered and became a favourite with everyone. The soldiers recovering in the ward all spoiled him rotten, teaching him English words and sending the Red Cross girls off to buy him toys. As one lot of patients left he’d cry but then cheer up as the next lot took over looking out for him.

The nurses were just as devoted and Mot often went looking for a cuddle from whichever nurse was on night duty. When the South Vietnamese authorities began calling to check on his progress, the nurses would get one of the doctors to tell them he was too sick to leave. Their subterfuge fell in a heap only when the authorities found out that the Red Cross girls were taking him to school. They took him away and sadly no one was ever able to find out what happened to him in spite of continued efforts even after the war.

With so much to be sad about, it’s easy to imagine they all wept a lot. However, despite the severity of some of the wounds they treated and the devastation those wounds caused to their young patients’ bodies, Terrie can only remember crying once. ‘I woke up one day when I was on night duty and found my stockings hanging up. I thought, Isn’t Mamma-san wonderful; she’s washed them for me. I put them on and went off to work.’ One of the other sisters came to work spitting chips and accused Terrie of stealing her stockings, even though she’d hung them near Terrie’s space. She was so furious, Terrie dissolved into tears. She rushed back to the quarters to strip them off and ran into her friend Mick, who asked her, ‘Whatever is wrong?’

Sobbing, she told him, ‘One of the girls said I stole her stockings.’

‘Oh my God,’ he said, ‘I thought your mother must have died.’

Living in such an intense environment, it was the little things that broke through the bravado and made people snap.

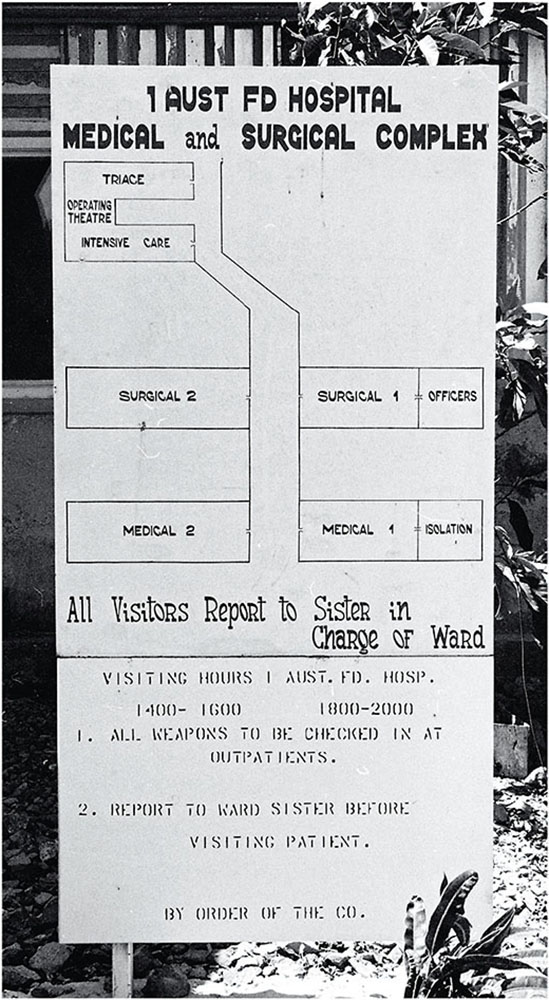

By the time Terrie and her original compatriots were getting ready to leave in May 1968, the number of casualties coming in had increased enormously. Earlier that year, in January, the Viet Cong had launched the Tet Offensive, a series of planned, prolonged assaults on South Vietnam, the United States and their allies that continued for several weeks. In April, the 8 Fd Amb had moved up to Nui Dat, leaving in its place the 1st Australian Field Hospital. Plans were afoot to expand the capacity of the facility by adding a dedicated triage, a second theatre and an extra surgical and medical ward.

Even though Terrie says she loved everything about the wonderful nursing experience that was her twelve months in Vietnam, by the end she was definitely ready for home. Back in Australia, she was posted to 8 Camp Hospital at Kapooka, south-west of Wagga Wagga in NSW, where she worked for a year to complete her commission. ‘It was a bit strange when we came back,’ she says, ‘because hardly anyone had been to South Vietnam and certainly no one at Kapooka, so there was really no one to talk to about it.’

She had Mick, though. Their friendship continued to simmer along happily and they married in 1972. Like all women in the military at that time, Terrie had to resign but Mick remained in the army for some years. Terrie says they’ve had a pretty good life together, welcoming both children and grandchildren with great joy.

In hindsight, even though they had some fun in Vietnam to relieve the overwhelming awfulness of the war and formed lifelong bonds – not least their own – it was a long, very intense year. Terrie sums up: ‘We worked very hard, but when we were able to we partied hard and had as much fun as we could. When I came home I never wanted to go back, but I’m not at all sorry that I went.’

One of the first four Army nurses to deploy to Vietnam in 1967, Terrie Roche, secures a sling on an Australian soldier at the 8th Field Ambulance, Vung Tau. Photograph by Denis Stanley Gibbons AM.

Terrie Roche disembarks from a chopper after returning from a function at Nui Dat, 1967. Photograph by Denis Stanley Gibbons AM.

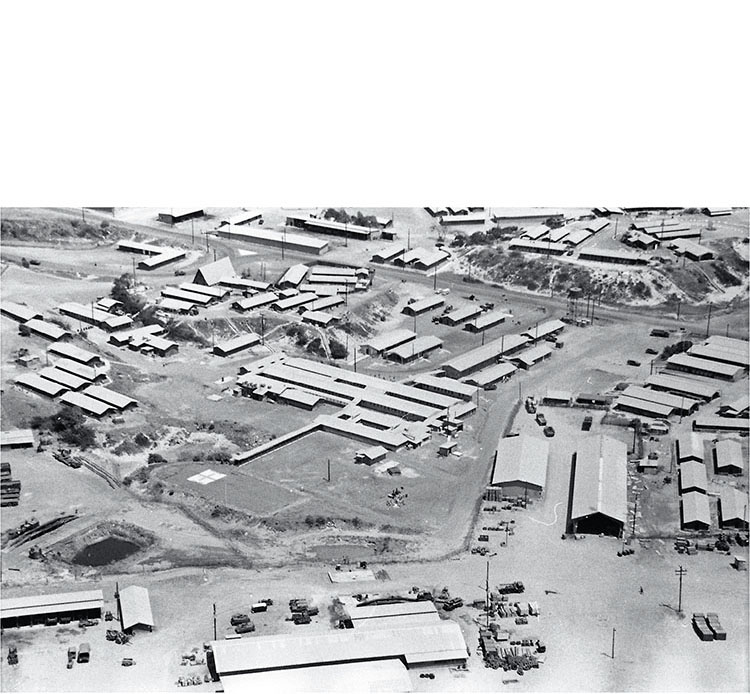

Aerial view of the 1st Australian Field Hospital, Vung Tau, 1970. Photograph by Denis Stanley Gibbons AM.

The sign for visitors at the 1st Australian Field Hospital directs that all weapons are to be checked in at outpatients and all visitors must report in to Sister. Photograph by Denis Stanley Gibbons AM.