7

Operating Theatre

June Naughton née Miinchow, RAANC

1st Australian Field Hospital,

December 1969–December 1970

It was the end of another long workday in the operating theatres of the 1st Australian Field Hospital at Vung Tau and June Miinchow was chatting with some of her new medical colleagues in the officers’ mess. For the first time since her arrival, she’d allowed herself a couple of drinks and was feeling nicely relaxed when the dustoff siren suddenly shrieked out across the complex. Shocked into almost complete sobriety as it reached full pitch, she scoffed down a mug of strong black coffee to make sure and, along with her on-call teammates, hit her straps. As she headed straight for triage and the operating theatres that were her particular battleground, June pledged to herself, No more alcohol while in Vietnam.

Out near the helipad, codenamed Vampire, a reception party made up of doctors, medics, OTTs (medics trained as operating theatre technicians), padres and Q store staff steadily gathered. Wound up with nervous expectancy by the siren’s wail, the medics expended a bit of their adrenaline-driven energy playing volleyball beside the big red landing cross as they waited for the first whisper of the Iroquois’s thump-thump-thump-thump to echo in from the north.

In triage and then theatre June checked yet again that everything was prepared and just as she’d left it, ready to receive the wounded she knew were coming.

A world away from the sugarcane fields of her childhood, June was exactly where she wanted to be, doing what she most wanted to do.

Growing up on a cane farm between Mackay and Proserpine in north Queensland, June Miinchow knew she wanted to be a nurse from the time she was two or three. She has no idea how or why she even knew what a nurse was at that young age, but her determination never wavered.

In 1957, having completed her schooling, June commenced training for her general nursing certificate at the Mackay Base Hospital. She loved everything about it from the beginning and when she learnt that one of her favourite tutor sisters was a nurse in the Army Reserve, that idea appealed to her so much she herself joined in 1959.

After she graduated as a registered nurse in 1960, June moved to Tasmania to undertake her midwifery training, a speciality she had enjoyed practising back in Mackay for a few months after she qualified. With her heart already set on theatre nursing, however, it wasn’t long before she applied to the Royal Perth Hospital to do an operating-theatre techniques and management course, training that consumed another twelve months.

By 1967, June had contributed enough time to the reserves to know that army life suited her somewhat reticent and self-disciplined nature, and she joined the regular army in the hope that she might be sent to Vietnam. She recalls, ‘I was just at that age when I needed and wanted to contribute something significant,’ adding that if she hadn’t joined the army she’d probably have volunteered to go with a civilian team from Perth.

June had her sights set on going with the second lot of Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps nurses who departed in May 1968; however, after six months at the regimental aid post at the Swanbourne SAS base in Perth, she was transferred to No 2 Military Hospital at Ingleburn near Sydney, where she spent two years honing her skills in the operating theatre.

As well as military patients from Ingleburn requiring routine and emergency surgery, any casualties from Vietnam who were evacuated back to Richmond by the RAAF ended up at 2 Mil. Many of them arrived with wounds packed and dressed in the theatres of the 1st Australian Field Hospital in Vung Tau and would have the next stage of their surgery in the 2 Mil theatres to complete those preliminary treatments. Others required ongoing surgery to complete repairs and/or reconstructions already begun. June became very familiar with these second-stage surgical patients, many of them amputees or men who’d been critically wounded by gunshot, grenade or the shrapnel from bomb blasts.

They were all kept at Ingleburn until they were stabilised enough to return to their home states, at which time the army organised commercial flights home for them accompanied by a Nursing Corps officer. Having escorted a few patients home herself, June says TAA and Ansett, the domestic airlines of the day, went above and beyond expectation to assist the returned servicemen, many of whom required special loading and multiple seats to accommodate their stretchers. The airlines would pull out all the stops, especially in December, even going so far as to bump regular citizens onto alternative flights so that they could fit the stretchers in and get the diggers home for Christmas.

By the time June received her notification of deployment to the 1 Fd Hosp at Vung Tau she had a lot of theatre experience and a pretty fair idea of what to expect. She was very comfortable working with army doctors and the operating theatre technicians who assisted them. Most of the OTTs were regular army medics who’d been specifically trained to work in theatre and many of those she worked with at Ingleburn were also destined for Vung Tau.

Although she felt well prepared for Vietnam professionally, June says, ‘There’s always a little element of doubt until you actually get there and see for yourself what’s happening. I was twenty-nine when I went but, other than New Zealand, I’d never been overseas and it was a bit daunting.’ Despite her doubts, and those of her mother, who was terrified and didn’t want her to go, June was not going to miss this opportunity. She says, ‘This was one thing I really was going to do and that was it.’ So, off she went.

Flying Qantas via Singapore, June arrived in Vung Tau just before Christmas in 1969. By chance, she had a couple of quiet days to settle in, meet the staff she hadn’t already met back in Australia and orient herself with the layout of the Australian Logistic Support Group compound and the 1 Fd Hosp, focusing particularly on the theatre, triage and recovery units where she would work for the next twelve months.

When June arrived in Vung Tau, the American 36th Evacuation Hospital had just closed down and the nearest American hospital was the 93rd Evacuation Hospital, 80 kilometres away at Long Binh. The 1 Fd Hosp had been extended to 100 beds and was well staffed and resourced to handle all medical cases and any general surgery, including multiple amputees. Any head injuries requiring neurosurgery and all critical burns or extremely complex orthopaedics still went to the Americans, whose much larger hospitals were superbly equipped to handle any contingency.

As confident as she was in her professional capabilities, June was still to be tried and tested emotionally. On Christmas Eve many of the staff, including June, were in their little Anglican chapel singing carols when one of the soldiers in the ALSG compound was killed, accidentally shot through the head by his mate. Enjoying the brief reprieve afforded by the promise of Christmas, the two lads had been clowning around when the gun went off. ‘And they were just boys,’ June says, ‘barely out of their teens. It was so very sad.’ With one of their young men in the morgue and another in shock, devastated by the unintentional death of his mate, Christmas was a subdued affair for the 1 Fd Hosp staff, focused on prayer, mateship and support for each other.

Not long afterwards, June heard the dustoff siren wind up to its full-pitched wail for the first time. Out in the field, as soon as anyone was wounded a radio call would go out to the Americans, who directed all such traffic, requesting a dustoff. The brave, talented pilots of the Iroquois choppers bearing the big red crosses flew in and landed when they could, or hovered when they couldn’t, winching the wounded off the jungle floor instead.

Meanwhile, back at the ALSG, as soon as the radio operators got the message that there was a dustoff in progress, they would advise the 1 Fd Hosp commanding officer and the siren would be triggered. When the chopper – or choppers – arrived, the reception party and any spare off-duty hands who turned up to help would, as directed by the admin officer, move into place to receive the wounded.

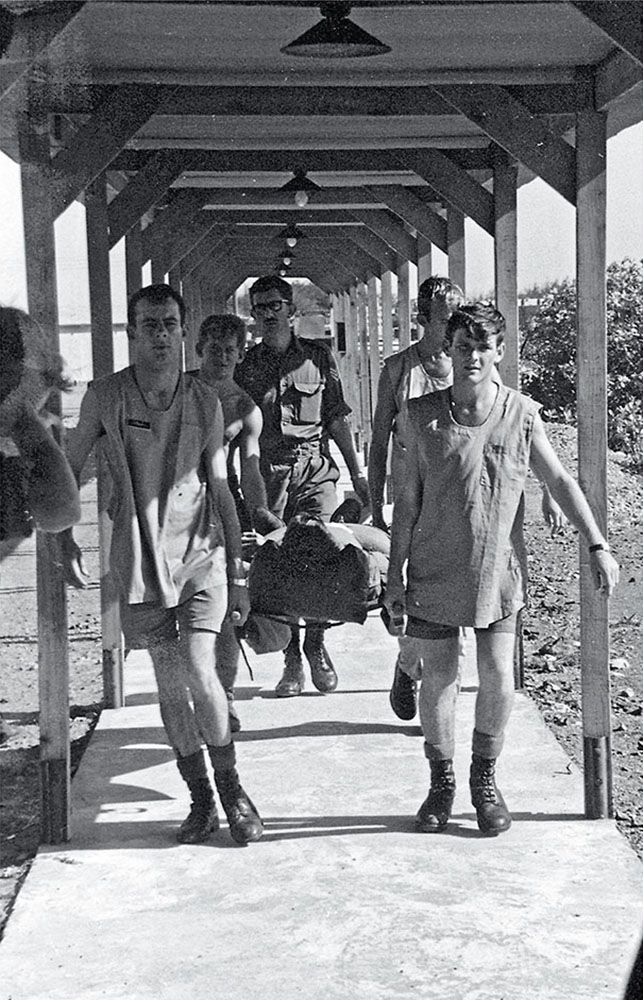

As soon as the first helicopter touched down, ducking under the swirling rotors, the team would pull the stretchers out of the side door of the aircraft, or guide the walking wounded as one of the senior surgeons took charge of assessing and directing the injured soldiers into triage. As the casualties came off the chopper, the Q store staff immediately assumed responsibility for any firearms, grenades or ammunition they might be carrying and disposed of them in the nearby weapons dump. Two men, or four if they were needed, carried the stretchers down the walkway into triage, a large, windowless, metal-walled, air-conditioned room with three permanent trolley bays on each side. Another two bays could be utilised if necessary. Ceiling rails ran the length of the room above the bays, carrying a clipboard full of forms and several bottles of intravenous fluids for each trolley, ready for immediate administration.

A huge whiteboard graced the wall in each bay; everything that happened to the patient would be recorded on it. Open shelves below the whiteboard stored a vast array of medical supplies, including infusion equipment and fluids, cut-down sets, airways, catheterisation packs, syringes and needles, scissors, sterile instruments and stacks of freshly sterilised dressing packs. Bags of blood were stored in the triage fridge ready for infusion when the cross matches were done. A mobile X-ray unit was located in triage and the trolleys had been specially designed to enable X-ray plates to be slotted in under the patient without moving him.

The stretcher-bearers would place their cargo on the floor beside the trolley nominated by the surgeon. The worst case always went to bay 1. As the bays filled, the noise level increased over the background growl of the engines and thump-thump-thump-thump of the departing choppers. In each bay a small team of doctors assisted by two operating theatre technicians would get to work. One of the OTTs would crouch down beside the stretcher on the floor and quickly begin slicing through the lacing on the injured soldier’s boots right up through his trousers and shirt with a pair of specially designed cutting shears. The clothes would be folded back, a small sheet draped over and then the soldier would be lifted up and held for a few minutes while a doctor quickly examined his back for obvious injuries before he was laid on the triage trolley for a more thorough examination.

While the doctors began treating the wounded, administering pain management, blood pressure management, fluid replacement and oxygenation, one of the clerks would be checking identifications, securing valuables, helping with the record of treatment and documentation, writing everything on the whiteboard beside each trolley. They’d write up what doses of morphine and penicillin had been given and when, what IV fluids, and record blood pressure, pulse and breath rate.

Describing the scene, June says, ‘You have to remember that we had no wonderful machines to measure things back then. We wrapped a sphygmomanometer around the arm, pumped it up and then released it, listening with a stethoscope to the echo of blood pumping through the brachial artery to measure blood pressure. We had no way of measuring blood oxygen levels. We had none of the infusion pumps they use these days to manage intravenous fluids, and no fancy monitors. All we had were a few basic tools, our eyes, our skills, our knowledge and instinct.’

June’s place was usually on bay 1, where she chose to stand at the head of the most critical casualty, holding his oxygen mask in place while she quietly explained everything that was happening to him. She liked to be able to reassure and comfort the soldier, maintaining close nurse–patient contact while people were sticking needles and things in him and he was learning just how badly injured he was. ‘It must have been terrifying for those young men to suddenly be so devastatingly wounded and so completely vulnerable.’

Despite that, she remembers their cheerfulness. One young fellow wanted to know what perfume she was wearing because it reminded him of home, while another admired her round eyes as she was explaining what the doctors were doing to him. Seeing and/or hearing the Australian nurses was important because of their association with home. The soldiers amused her sometimes. As she was oxygenating a little guy one day she heard him say, ‘Thanks, Mum, for making me so short.’ A bullet had ploughed a furrow through his scalp and through the bone on top of his head but had not quite breached it.

Although all members of the military had their blood group written on their dog tags, no one relied on it being accurate and anyone who needed a transfusion was cross-matched by the lab on arrival in triage. The pathologist often helped in triage until the first tests were ready. Moving in and around the action, the pathology technicians came and collected the rest of the blood samples from the doctors and took them back to the pathologist in the lab for immediate attention so that transfusions could be commenced as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, the portable X-ray machine would be doing the rounds of triage, being hauled to whichever bay it was needed in so the radiologist could take the pictures requested by the admitting doctors and go off to develop them in a small room near the main entrance.

The padres were an integral presence in triage, reassuring and comforting everyone and assisting where asked. There were three of them, one Catholic, one Anglican and one from one of the other Protestant denominations, although all of them were interdenominational when it came to supporting the wounded. As time went on, June taught one of the padres how to administer oxygen so that he could either relieve her or be doing the same role in bay 2 when necessary.

This was triage: a constant flow of people moving in and out and around, doing whatever job was required of them.

Being positioned at the head of bay 1 had its advantages. From there June could observe how the OTTs were managing and when they might be ready to move in and start setting up their positions in the operating room. As soon as the most critical surgical patient was ready, he would be moved into theatre and, under the direction of the senior surgeon, onto one of the operating tables. With three tables available, the teams moved straight from triage with their charges and operated until all surgery was completed.

As a rule, each operation would involve the surgeon, an assistant surgeon, the anaesthetist, an OTT assisting the anaesthetist with the massive blood transfusions and fluid replacement often required, an OTT scrubbing (selecting and handing over instruments) plus an OTT scouting, a ‘gofer’ for anything extra that was needed for the most serious cases. June supervised the OTTs in both theatres and helped out where necessary. If an OTT needed some guidance, June would watch over his shoulder and direct for as long as necessary but, she says, ‘They rarely needed advice. They were well trained and competent. They knew what they were doing.’

Once the anaesthetist had the patient asleep, June would prepare the operation site while the techs were setting up the sterile trays and instruments. She laughs as she recalls how adept she became with a cut-throat razor. ‘I’d never used one before but I had a lot of practice up there.’ She had proper skin-prep packs to clean the part of the body they were repairing and would do a proper compound scrub with sterile water, chlorhexidine and a little scrub brush. ‘We cleaned the area completely and arranged sterile drapes over everything but the wound site, so that the doctors were working in an area that was as clinically clean as possible.’

Once they had stopped the bleeding, they would clean and debride each wound, cutting away any dead or damaged tissue, before packing and dressing them. June says, ‘Most of the time with the traumatic injuries there was so much tissue damage, it was impossible to suture the wound immediately.’ Further debridement and delayed primary closure would take place on return visits to the operating theatre over the next couple of days or even, after evacuation, back in Australia as a second- or third-stage procedure.

And so the surgical teams would work through the operating list, finishing up with the less urgent cases, men whose wounds could be cleaned and sutured, who would recuperate in the wards of the 1 Fd Hosp and then return to the battlefield.

As each patient’s surgery and their recovery from the anaesthetic was completed, they would be moved either to ICU or back to the ward depending on the severity of their situation. When they left theatre, that was it for June, who no longer had any part in their progress unless they were returned to theatre for further surgery. Her role was specifically attached to triage and theatre.

After each procedure, the OTTs would clean up and prepare the theatre ready for immediate use. They’d wash all the theatre linen prior to it being delivered to a Vietnamese laundry in Vung Tau. They’d wash all the instruments, then sterilise and repack them ready for autoclaving. Finally they’d clean the tables and trolleys in theatre and triage and wash all the floors.

The doctors who went to the 1st Australian Field Hospital were reputed to be some of the very best specialists in Australia. Most were either in defence force reserves or were specialists inducted into the army for the duration of their deployment to Vietnam. Some of them were women; they had a female physician, a female pathologist, and also a female anaesthetist who, in June’s opinion, had the toughest job. ‘When you think about it, the physician would see some of her patients in the medical ward so they might have malaria or hepatitis or some other illness, and the pathologists spent a lot of time in the lab away from the direct action, but the anaesthetists spent all their time in triage or theatre and saw only trauma patients.’

June felt for one newly arrived anaesthetist who didn’t realise that her first dustoff was a dummy run. When they had been quiet for a few days, the CO would often drop a practice run on the medical team so that they were always right on the ball, ready to go, when the siren went for real. The anaesthetist was so worked up worrying about her first dustoff, she was quite angry and upset when she learnt it wasn’t real. ‘Some of them were pretty young considering the responsibility they carried,’ June says.

In an effort to manage the emotional fallout of living and working in such a tense environment, discipline was quite strict. Officers and other ranks didn’t mix socially. Even in her baggy theatre scrubs and cap, June was a striking-looking young woman with fair hair and green eyes who wasn’t much older than some of the fourteen male OTTs she consistently worked with and supervised. Most of them were regular army medics who’d been trained as theatre technicians, but a handful of them were conscripts, national servicemen barely out of their teens. She found sticking to the rules made it easier to maintain the status quo. Considering her strict but fair, they all called her ‘Boss’ to her face, though, she says with a smile, ‘They sometimes called me “mother” behind my back and probably a few other terrible things I never heard about.’ Years later, when one of them called their first daughter June, she wondered whether it was a compliment or coincidence.

For her part, June has nothing but admiration for the medics-cum-theatre technicians who worked for her. Earnestly she says, ‘They were highly proficient and it’s an indication of their value that, in today’s army, those same fourteen theatre technicians would be replaced by fourteen registered nurses.’

After that fateful night when she decided not to drink alcohol again during her deployment, June rarely set foot in the mess, deciding instead to spend her off-duty evenings in triage with any available surgeons and anaesthetists discussing the day’s activities with the OTTs, training them, and especially the national servicemen, in different procedures and techniques. The OTTs weren’t allowed to drink when they were on call, so it served to occupy their time as well as enhance their knowledge and skills.

In hindsight, June realises that those sessions in triage after dinner probably constituted the debriefings that no one was ever offered back in those days because no one understood their significance. The fact that the sessions were only for theatre staff meant the boys had a very strong feeling of belonging to the theatre team; it tightened the threads that bound them and they worked as a close-knit unit. It caused occasional friction among the medics because the OTTs had so much more to do with the doctors than the other medics did; although June didn’t realise it at the time, it also distanced her from the other nurses, but she was happy doing what she was doing and didn’t worry about it. She had a couple of close friends among the nurses who provided all the ‘girl-time’ she needed.

On reflection, she says, ‘I’m not a very social person and I had quickly realised that I couldn’t party on even if I wanted to. Aside from being on call, by the time you washed and ironed, wrote letters home and got prepared for the next day, there wasn’t a lot of time for much else.’

Being on call meant she sometimes worked very long days; her longest session was thirty-six hours. ‘We’d just finish up and get the theatre cleaned up and the siren would go again.’ The strength of the team spirit at the hospital was perhaps best illustrated by the kitchen staff, who always had a hot meal ready for the theatre teams. ‘We wouldn’t have eaten all day but when we finished the cook would always have something there for us, even at 3 o’clock in the morning.’

When the siren sounded the theatre staff had no way of knowing whether it was one casualty coming in or a dozen, though the CO would often walk down and let them know whatever information he’d been given when the first radio calls came through. June always worked on the premise that she could be called out again at any time. Primarily, the dustoffs brought in Australians, although sometimes an American might come in. By the time June was there, the 36th Evacuation Hospital at Vung Tau had closed down and the 1 Fd Hosp was often a closer option than the American hospitals at Long Binh or Saigon.

Very occasionally they’d have an emergency with no warning. They were cleaning up one day after a particularly busy dustoff when June sent one of the OTTS out to clean up the triage. Next thing he raced back in saying, ‘Sister, quick, there’s casualties out there everywhere and some of them are dead!’ As it happened, they were Koreans who’d come in on one of their own choppers without radioing the Americans; they just arrived. On even more rare occasions, the theatre staff operated on Viet Cong prisoners of war, or civilian casualties brought in to the 1 Fd Hosp because it was closest.

In the course of a normal day, however, they might be very quiet and spend the day sterilising instrument packs or autoclaving linen packs in the central sterilising department (CSD) of the theatre complex. They might check and restock their supplies, and there was always cleaning and polishing to fill an idle moment. When she had time, June would bake cakes in the CSD. With a small laugh she explains that the dry heat autoclave was perfect for baking, although they didn’t exactly have the facilities for doing it from scratch. Instead, the OTTs got their mothers, wives or girlfriends to send them ready-mix cakes that they could mix up in a surgical bowl and bake in an instrument tray. It was a real treat for the boys, as were the beers June occasionally allowed them while they were doing their training sessions in triage after dinner on quiet nights.

They were never quiet for long, though. All too soon, the machinations of war would send another onslaught of casualties their way.

When her twelve-month deployment ended in December 1970, June was posted back to No 1 Military Hospital in Brisbane. She arrived home on leave in time for Christmas, but her father had a massive stroke just after she got there and she spent a subdued couple of weeks helping her mother and sister come to terms with his prognosis. It rather overshadowed her return and she really didn’t discuss her experience in Vietnam much with anyone.

While she had no set plan to stay in the army, June continued her commission until 1979. During that time, the army changed the rules about fraternisation and marriage, leaving June free to marry Dr Michael Naughton, a man she’d known for many years and who was, in fact, the CO at 1 Fd Hosp while she was there.

In their working situation in Vung Tau, June and Michael saw a lot of each other, although they were very rarely alone. June wasn’t even aware that anyone else knew of their mutual interest until the day Michael went out in one of the dustoff choppers to familiarise himself with exactly what happened right along the chain of retrieval. When the helicopter crashed, the senior surgeon made a point of finding June and telling her that Michael was okay. She appreciated the information even though she was surprised to discover that the other officers were aware of their connection.

Their relationship was founded on profound respect for each other and solid friendship. They married on 20 December 1974, and on Christmas Day Michael was sent to Darwin to clean up after Cyclone Tracy. He was gone for three months. June went back to live in the mess at 1 Mil until he came home.

When she finally resigned from the army with the rank of major in 1979, June did an Arts degree while nursing in theatre part-time. A couple of years later, she successfully applied for the position of charge sister in the theatres at Greenslopes Repatriation Hospital in Brisbane. When the complex was scheduled for extensive renovations, the management appointed June as nursing representative on the project team, a role she found she enjoyed immensely.

Later still, when nursing training was moved out of the hospital system and into universities, June decided to refocus her career, enrolling at the Queensland University of Technology to study interior design. It had always interested her and, influenced by her experience on the project team at Greenslopes, once qualified she joined an architectural firm designing hospitals, juggling that job with working part-time in theatre at the Mater Private Hospital. June was fascinated by the architectural work and realised she had a lot to contribute when she discovered that the architects thought ‘theatre’ meant ‘lecture theatre’. She was able to translate briefings for them and guide them in practical ways as they designed the future work environments of the medical world.

Looking back, June says her career has been both interesting and fulfilling and that she’d always encourage anyone interested in nursing to go for it – especially her favourite, theatre nursing, because ‘it’s always very exciting to see the tangible results of your work’. Her years working in hospital design also allowed her to contribute substantially to modern medicine, while accommodating her creative bent.

It was her year in Vietnam, however, that was the highlight of her professional journey and the one that was most rewarding. When those soldiers arrived in her theatre, they were nearly all very young, very fit and critically compromised. For June it was, and still is, extremely satisfying to know that she and her team of theatre technicians played an integral role in their resuscitation and recovery.

Theatre nurse June Miinchow holds the oxygen mask on the most critically wounded soldier in Bay 1 in triage while he is assessed and treated by doctors. Photograph by Denis Stanley Gibbons AM.

Yet another dustoff chopper ensures a very busy triage as doctors assess and prioritise the incoming wounded. Photograph by Denis Stanley Gibbons AM.

Medics carry in a stretcher from a dustoff chopper newly arrived on Vampire, the helipad outside the 1st Australian Field Hospital, 1970. Photograph by Denis Stanley Gibbons AM.