It is said sometimes of the Gestapo, and not only of the Gestapo, but also of the S.S. in general, and of those members of the Armed Forces and of the civilian bureaucracy (they may fairly regard themselves as an ill-used minority) who have been unable to escape being implicated in the slaughter of the Jews and the Slavs, that they had become so conditioned to regarding these people as not people at all, as subhuman types, that they felt not merely no compunction in removing them from the earth but also a positive pride. This contention has a basis of truth. We remember Himmler’s description of the extermination of the Jews as a delousing operation, and we may cite the words of S.S. Lieutenant General Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski at Nuremberg, when asked to comment on the massacres of the Einsatzgruppen: “I am of the opinion that when, for years, for decades, the doctrine is preached that the Slav race is an inferior race and Jews not even human, then an explosion of this sort is inevitable.” Bach-Zelewski was an educated man, an old soldier, a Higher S.S. and Police Leader in charge of operations on the Rusian Front, and a member of the Reichstag from 1932 until the end.

We shall return to this view later. The point to be made immediately is that the Gestapo, the S.S., and others did not confine their extraordinary activities to people whom they considered inferior or subhuman. They operated with equal cruelty against the nations of the West. It is true that there was no campaign of extermination directed against, for example, the French; but this was due to a political decision made by Hitler. We have no reason to doubt that had the Fuehrer decided to eliminate ten million Frenchmen in order to make room for Germans, the relevant organizations, including the Gestapo and the S.D. would have carried out his orders, even thought they had not been taught for years that the French were subhuman. Indeed, although extermination of whole sections of the population was never practiced in Western Europe—always excepting the Jews, whom the people of several nationalities, and especially the French, perversely insisted on regarding as their own compatriots—there were some by no means inconsiderable massacres, not only of civilian populations but also of prisoners-of-war; and on those occasions when the Gestapo were required to act with severity against groups and individuals, there was nothing to choose between their behavior in Bourges and their behavior in Borisov. Only those who think that, in these days, individual murder must be multiplied a thousand-fold before it may be considered reprehensible will find any fundamental variation in the general attitude and behavior of the Gestapo wherever it happened to be stationed. If there is some confusion about this, it may be found to be due very largely to the invention of a new word to describe what was, at Nuremberg, considered to be a new crime: the word genocide, which may be seen as one of those camouflage terms. It is meant to sound formidable; but in fact it serves all too well to conceal the simple fact of murder.

There was plenty of murder in Western Europe, but no genocide. Most of it took place—always excepting the mass-murder of the Jews—when Germany was hard put to it to hold her own against the Allies; and most of it came into the category of kiling for punishment, or as a deterrent, rather than into the category of killing to exterminate. There was the shooting of hostages on a large scale, to cow the spirit of resistance; there was the torturing and killing of individuals suspected of sabotage; there was the killing of prisoners-of-war, mainly British, who made a nuisance of themselves; there was the killing of captured parachutists and Commandos, mainly British, to discourage the others. There were special expedients, such as the decree which instructed the police not to interfere with angry crowds when they started lynching Allied bomber-crews who had been shot down, or such as the notorious Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog) Decree, which provided that all suspected resisters who could not be shot out of hand were to be sent in conditions of the utmost secrecy to Germany, where their fate would be concealed, even after death, from their families—the object of this being to create an atmosphere of secret and mysterious terror inimical to the spirit of resistance. In all these operations the Gestapo and the S.D. operated in the foreground, as in the rounding-up and deportation of the Jews—not, as they were compelled to do at Auschwitz and elsewhere, in the background at comparatively long range.

At Nuremberg on February 4th, 1946, the courtroom was suddenly invaded by a sense of humanity. Until then the onlookers had become so attuned to tales of wickedness and horror that their feelings had been numbed; and even when, as very often, they were required to listen to the pitiful evidence of individuals, ordinary men and women who had been assailed by the Nazi machine, but had miraculously escaped, the scale of inhumanity was so immense that the personal disaster seemed to count not as a human tragedy but simply as one more squalid item in the tremendous case being so laboriously assembled. But now, for once, there was a real human being speaking and in language all could understand: the Belgian scholar, the historian, van der Essen, General Secretary of the University of Louvain.

Nothing much had happened to Professor van der Essen. He had had a lucky war. His beloved university library had been wrecked by the Germans, but he had not been hurt, and he had moved about, a free man, during the whole period of the occupation. He was detached from the suffering all around him (if he had allowed himself to participate he would have gone mad) and, his body unbroken, his mind unclouded, and in no immediate personal fear, he was in a position to observe the afflictions of the less fortunate. Thus his evidence, though unspectacular and almost dull, in which he gave an account of life as lived in the shadow of the Gestapo, has a point and actuality which helps to make sense in the catalogue of horrors to which we must soon return.

“I think I understand,” said M. Faure, a member of the French Prosecution, who was later to become Prime Minister of France, “that you yourself were never arrested or seriously worried by the Germans. I would like to know whether you consider that a free man, against whom the German administration or police have nothing in particular, could during the Nazi occupation lead his life in accordance with the concept a free man has of his dignity?”

So this rare, this almost unique, apparition at Nuremberg, a man who had neither suffered physical violence nor inflicted it, set himself earnestly to trying to give a sober impression of the German occupation as experienced by a man with nothing to fear. He held the court. His story on the face of it was an anticlimax; but in fact it underlined more than anything else the reality behind the fantasy of murder and cruelty which, until then, had dominated the whole proceedings. He started off by saying that he weighed eighty-two kilos “before May 10th, 1940, before the airplanes of the Luftwaffe suddenly came without any declaration of war and spread death and desolation in Belgium.” He now weighed sixty-seven kilos. There was that small fact to begin with. One of the German defense counsel, who failed to sense the mood of the court, Herr Dr. Babel, tried a remark that was half a joke and half a sneer: “During the war, I also, without having been ill, lost 35 kilos. What conclusion would you draw from that, in your opinion?” There was laughter in court, but the President cut in, “Go on; Dr. Babel, we are not interested in your experiences.”

Professor van der Essen said:

“I don’t want to dwell on personal considerations or enter into details of a personal nature or of a theoretical or philosophical nature. I should like simply to give an account—it will not take more than two minutes—of the ordinary day of an average Belgian during the occupation.

“I take a day in the winter of 1943: at six o’clock in the morning there is a ring at the door. One’s first thought—indeed we all had this thought—was that it was the Gestapo. It wasn’t the Gestapo. It was a city policeman who had come to tell me that there was a light in my office and that in view of the necessities of the occupation I must be careful about this in future. But there was the nervous shock.

“At seven-thirty the postman arrives bringing me my letters; he tells me that he wishes to see me personally. I go downstairs and the man says to me, ‘You know, Professor, I am a member of the secret army and I know what is going on. The Germans intend to arrest today at ten o’clock all the former soldiers of the Belgian Army who are in this region. Your son must disappear immediately.’ I hurry upstairs and wake my son. I make him prepare his kit and send him to the right place. At ten o’clock I take the tram for Brussels. A few kilometres out of Louvain the tram stops. A military police patrol makes us get down and lines us up—irrespective of our social position—in front of a wall, with our arms raised and facing the wall. We are thoroughly searched, and having found neither arms nor compromising papers of any kind, we are allowed to go back into the tram. A few kilometres farther on the tram is stopped by a crowd which prevents the tram from going on. I see several women weeping, there are cries and wailings, I make enquiries and am told that their men folk living in the village had refused to do compulsory labor and were to have been arrested that night by the Security Police. Now they are taking away the old father of eighty-two and a young girl of sixteen and holding them for the disappearance of the young men.

“I arrive in Brussels to attend a meeting of the academy. The first thing the President says to me is:

“ ‘Have you heard what has happened? Two of our colleagues were arrested yesterday in the street. Their families are in a terrible state. Nobody knows where they are.’

“I go home in the evening and we are stopped on the way three times, once to search for terrorists, who are said to have fled, the other times to see if our papers are in order. At last I get home without anything serious having happened to me.

“I might say here that only at nine o’clock in the evening can we give a sigh of relief, when we turn the knob of our radio set and listen to that reassuring voice which we hear every evening, the voice of Fighting France. ‘Today is the one hundred and eighty-ninth day of the struggle of the French people for their liberation,’ or the voice of Victor Delabley, that noble figure of the Belgian Radio in London, who always finished up by saying, ‘Courage, we will get them yet, the Boches!’ That was the only thing that enabled us to breathe and go to sleep at night.”

It is very quiet and unsensational, and Professor van der Essen was not hurt. And yet so many aspects of Gestapo rule are there, just below the placid surface. The knock at the door, which is not the milkman; the son being packed off into hiding at a moment’s notice; the round-up of ex-soldiers to be sent to concentration camps or forced labor; the seizing of hostages—the old man and the young girl, for shooting in case of need; the arrest of university dons in broad daylight in the streets of Brussels and their disappearance into Night and Fog; the listening to the nine o’clock news from London—but in French, not English—because the English intonation would be noticeable in itself, and listening to the English wireless meant arrest.

Professor van der Essen was not an innocent. He knew what was going on. He was not an active resister, but it was only luck that saved him; the luck of not being a Jew that saved him from almost certain death; the luck of not being picked up as a hostage that saved him from probable shooting, certain imprisonment. ‘When hostages were taken it was nearly always university professors, doctors, lawyers, men of letters.” This was a settled policy. It was laid down for the whole of occupied Europe that hostages, to be shot if a German was killed, often in the proportion of one hundred to one, were to be people who were well known in their districts, well liked, and certain to be widely missed.

And behind these actions were the men who, on the other side of Europe, were slaughtering millions in conditions of inconceivable “barbarism and calling their slaughter a delousing action.

It was in France, after the total occupation, and at a time when the Resistance had become serious, that the local commanders of the Gestapo and the S.D. showed that they were made of the same stuff as the Globocniks, the Kruegers, the Mildners, and the rest. And, as in the East, they found they could always call on the Waffen S.S. and nearly always on the Wehrmacht. In the closing stages of the war, when the Germans were on the run, the Gestapo could not begin to cope with the militant Resistance, and then the Waffen S.S. as at Oradour-sur-Glâne, carried out by themselves the sort of actions which they had so often practiced in the East.

But earlier the Security Police and the S.D. were able to manage fairly well on their own. They maintained a constant pressure of terror, which might strike at any time. Professor van der Essen was extremely lucky:

“Professors from Louvain were sent to Buchenwald, to Dora, to Neuengamme, to Gross-Rosen, and perhaps to other places too. I must add that it was not only professors from Louvain who were deported, but also intellectuals who played an important rôle in the life of the country. I can give you immediate proof. At Louvain, on the occasion of the reopening ceremony of the university this year, as Secretary General of the University, I read out the list of those who had died during the war. The list included three hundred and forty-eight names, if I remember rightly. Perhaps some thirty of these names were those of soldiers who died during the Battles of the Scheldt and the Lys in 1940, all the others were victims of the Gestapo, or had died in camps in Germany, especially in the camps of Gross-Rosen and Neuengamme.”

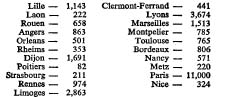

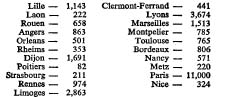

At Nuremberg the French Prosecution gave a list of figures, which was an anonymous roll of honor. The figures referred to the number of hostages taken from the civilian population and shot by the Germans in revenge for attacks on the occupation forces. And yet the list is not quite anonymous, because the figures break down into regions. And some of the many memorials scattered along the tourist roads of France commemorate the names behind these figures. Here they are, region by region:

The total is twenty-nine thousand, six hundred and sixty. Notices of the executions would be put up on posters, or published in the Press. Here is one such notice taken from Le Phare of October 21st, 1941:

“Cowardly criminals in the pay of England and of Moscow killed, with shots in the back, the Feldkom-mandant of Nantes on the morning of October 20th, 1941. So far the assassins have not been apprehended.

“As expiation for this crime I have ordered that fifty hostages be shot initially. Because of the gravity of the crime, fifty more hostages will be shot if the guilty have not been arrested between now and October 23rd midnight.”

Most of the executed hostages in this case, as in many others, were known Communists, and they were chosen from a list furnished by the Vichy Minister of the Interior, Peucheu, who was to be tried and hanged by his countrymen after the war. What went on at these shootings is described by the Abbé Moyon, who was a witness of a part of the consequences of the Nantes affair:

“It was a beautiful autumn day. The temperature was particularly mild. There had been lovely sunshine since morning. Everyone in town was going about his usual business. There was great animation in the town, for it was Wednesday, which was market day. The population knew from the newspapers and from the information it had received from Nantes that a senior officer had been killed in a street in Nantes, but refused to believe that such savage and extensive reprisals would be applied [it was still only 1941]. At Choisel Camp the German authorities had, for some days, put into special quarters a certain number of young men who were to serve as hostages in case of special difficulties. It was from among these men that those who were to be shot on this evening of October 22nd were chosen.

“The Curé of Béré was finishing his lunch when M. Moreau, Chief of Choisel Camp, presented himself. In a few words the latter explained to him the object of his visit. Having been delegated by M. Lecornu, the subprefect of Châteaubriant, he had come to inform him that twenty-seven men selected from among the political prisoners at Choisel were going to be executed that afternoon; and he asked Monsieur le Curé to go immediately to attend them. The priest said he was ready to undertake this mission, and he went to the prisoners without delay.

“When the priest appeared to carry out his mission, the subprefect was already with the condemned. He had come to announce the horrible fate which was awaiting them, and he asked them to write letters of farewell to their families without delay. It was under these circumstances that the priest presented himself at the entrance to the quarters.”

That was at Châteaubriant. The same thing was going on in the prison of La Fayette at Nantes itself, where sixteen were to be shot:

“The condemned were all very brave. It was two of the youngest, Gloux and Grolleau, who were students, who constantly encouraged the others, saying that it was better to die in this way than to perish uselessly in an accident.

“At the moment of leaving, the priest, for reasons which were not explained to him, was not authorized to accompany the hostages to the place of execution. He went down the stairs of the prison with them as far as the car. They were chained together in twos. The thirteenth had on handcuffs. Once they were in the truck, Gloux and Grolleau made another gesture of farewell to him, smiling and waving their hands, which were chained together.”

The priest had not been able to go to the place of execution at Châteaubriant, either. But a French police officer, Roussel, saw the condemned men being driven off, and later, brought back:

“The 22nd of October, 1941, at about three-thirty in the afternoon, I happened to be in the rue du 11 Novembre at Châteaubriant, and I saw coming from Choisel Camp four or five German trucks, I cannot say exactly how many, preceded by an automobile in which was a German officer. Several civilians with handcuffs were in the trucks and were singing patriotic songs, the ‘Marseillaise,’ the ‘Chant du Depart,’ and so forth. One of the trucks was filled with armed German soldiers.

“I learnt subsequently that these were hostages who had just been fetched from Choisel Camp to be taken to the quary of Sablière on the Soudan Road to be shot in reprisal for the murder at Nantes of the German Colonel Hotz.

“About two hours later these same trucks came back from the quarry and drove into the court of the Châteaubriant, where the bodies of the men who had been shot were deposited in a cellar until coffins could be made.

“Coming back from the quarry the trucks were covered and no noise could be heard, but a trickle of blood escaped from them and left a trail on the road from the quarry to the castle.

“The following day, on October 23rd, the bodies of the men who had been shot were put into coffins without any French persons being present, the entrances to the château having been guarded by German sentinels. The dead were then taken to nine different cemeteries in the surrounding communes, that is, three coffins to each commune. The Germans were careful to choose communes where there was no regular transport service, presumably to avoid the population going en masse to the graves of these martyrs.”

Police officer Roussel could not know it, but there was a standing order about this, and for the reasons which he guessed. For the shooting of hostages, as nothing else, bound the population together; and it is without surprise that we read the protest of General Falkenhausen, Military Governor of Belgium, to Keitel, dated September 16th, 1942:

“Enclosed is a list of the shooting of hostages which have taken place until now in my area and the incidents on account of which the shootings took place.

“In a great number of cases, particularly in the most serious, the perpetrators were later apprehended and sentenced.

“The result is undoubtedly very unsatisfactory. The effect is not so much deterrent as destructive of the feeling of the population for right and security; the gulf between the people influenced by Communism and the remainder of the population is being bridged; all circles are becoming filled with a feeling of hatred towards the occupying forces, and effective inciting material is given to enemy propaganda. Thereby military danger and general political reaction of an entirely unwanted nature …”

A similar protest was sent in also to Keitel, by the Commander of the Wehrmacht in Holland. But the shootings went on, sometimes carried out by the Security Police, sometimes by the Wehrmacht, who in the West as in the East were relied on to make up for the numerical weakness of the Gestapo.

From early in 1942, however, the dominating horror of the occupation was the notorious Nacht und Nebel Decree. It was thought up by Hitler, promulgated by Keitel, and issued to the Security Police by Himmler in the following form:

“I. The following regulations published by the Chief of the High Command of the Armed Forces, dated December 12th, 1941, are being made known herewith.

“(1) The Chief of the High Command of the Armed Forces. After lengthy consideration, it is the will of the Fuehrer that the measures taken against those who are guilty of offenses against the Reich or against the occupation forces in occupied areas should be altered. The Fuehrer is of the opinion that in such cases penal servitude or even a hard labor sentence for life will be regarded as a sign of weakness. An effective and lasting deterrent can be achieved only by the death penalty or by taking measures which will leave the family and the population uncertain as to the fate of the offender. Deportation to Germany serves this purpose.

“The attached directives for the prosecution of offenses correspond with the Fuehrer’s conception. They have been examined and approved by him.”

Himmler elaborated on this:

“The decree introduces a fundamental innovation. The Fuehrer and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces orders that offenses committed by civilians in occupied territories … are to be dealt with by the competent military courts in the occupied territories only if: (a) the death penalty is pronounced, and (b) sentence is pronounced within eight days of the prisoner’s arrest.

“Unless both these conditions are fulfilled, the Fuehrer and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces does not anticipate that criminal proceedings within the occupied territories will have the necessary deterrent effect.

“In all other cases the prisoners are, in future, to be transported to Germany secretly, and further treatment of the offenders will take place here; these measures will have a deterrent effect because: (a) the prisoners will vanish without leaving a trace; (b) no information may be given as to their whereabouts or their fate.”

There followed instructions as to the reporting of cases for deportation to Germany directly to the Director of the Kripo at the R.S.H.A. in Berlin.

Six months later we have a letter from the Chief of Security Police and S.D. which goes over the old ground and emphasizes that the mystery surrounding Nacht und Nebel prisoners is to persist after their death:

“I therefore propose that the following rules be observed in the handling of cases of death:

“(a) Notification of relatives is not to take place.

“(b) The body will be buried at the place of decease in the Reich.

“(c) The place of burial will, for the time being, not be made known.”

The Security Police in the Reich and all over Europe had absolute jurisdiction over the whole population. They could arrest. They could interrogate and torture. They could arrange with summary military courts whether a death sentence was desirable or not. And, if it was not, the victims were deported to Germany and passed by the home-based Security Police to the concentration camps, where most of them died.

But it was not only over the civilian populations that the Security Police held this absolute sway. There were also categories of the Allied Armed Forces which had to be surrendered to them by the Wehrmacht. In every camp for Russian prisoners-of-war there was a small Gestapo screening-team whose job it was to comb out undesirables—i.e., “political, criminal, or in some other way intolerable elements among them.” Russian prisoners-of-war, like all others, were the responsibility of the Army. But it was laid down that the Security Police screening squads could in no way be interfered with and were the absolute arbiters of which prisoners should be taken away and executed. In a Gestapo directive of July 17th, 1941, the squads were told how to set about their task:

“The Commandos must make efforts from the beginning to seek out among the prisoners elements which would appear reliable, regardless of whether they are Communists or not, in order to use them for intelligence purposes inside the camp and, if advisable, later in the occupied territories also.

“By use of such informers and by use of all other existing possibilities, the discovery of all elements to be eliminated among the prisoners must proceed, step by step, at once. The Commandos must find out definitely in every case, by a short questioning of those reported and possibly by questioning other prisoners, what measures should be taken. The information of one informer is not sufficient to designate a camp inmate to be a suspect without further proof. It must be confirmed in some way, if possible.…”

These instructions give in a very convenient form a clear idea of the methods of the Gestapo everywhere. What they came to in practice was indicated by General Lahousen, not of the S.S., in his evidence for the Prosecution at Nuremberg. Lahousen belonged to the Military Intelligence organization, or Abwehr, of Admiral Canaris, who was later executed for plotting against Hitler. Canaris and his Abwehr were at daggers drawn first with Heydrich, then with Kaltenbrunner and the Security Police in general; and this was not only because the Security Police and the S.D. in particular was constantly poaching on the preserves of Military Intelligence (in the end, after Canaris’ execution, the S.D. took the whole outfit over, so that the German Army was unique in the world in having no Intelligence of its own) but also because Canaris and his friends were wholly revolted by the methods of the Security Police and the S.D. General Lahousen said:

“The prisoners were sorted out by commandos of the S.D. and according to peculiar and utterly arbitrary ways of procedure. Some of the leaders of these Einsatzkommandos were guided by racial considerations, particularly of course, if someone were a Jew or of Jewish type or could otherwise be classified as racially inferior, he was picked for execution. Other leaders of the Einsatzkommandos selected people according to their intelligence. Some had views all of their own and most peculiar, so that I felt compelled to ask Mueller: ‘Tell me, according to what principles does this selection take place? Do you determine it by the height of a person or the size of his shoes?’ ”

(We are reminded of the notorious Gestapo round-ups in France, ostensibly to send Frenchmen to work in Germany, actually, as a rule, to consign them to concentration camps. “Certain German policemen were especially entrusted to pick out Jewish persons, according to their physiognomy. They called this group ‘The Physiognomists Brigade.’ ”)

Sometimes the Russian victims of the Gestapo screening-operations were shot then and there—but some way from the camp. More frequently they were sent off to concentration camps, where they were executed or worked to death. It is worth recalling that the man in Berlin who directly supervised these activities was S.S. Colonel Kurt Lindow, the gentlemanly Gestapo man who gave evidence at the trial of Heinrich Baab, and was afterwards taken away.

Soviet prisoners-of-war were not the only ones to come into the hands of the Gestapo. On March 4th, 1944, Mueller issued an instruction to the Security Police and the S.D. which became known as the Kugel Erlass, or Bullet Decree, which provided that certain categories of prisoners-of-war were “to be discharged from prisoner-of-war status” and handed over to the Secret State Police by the Army. These categories included all Soviet prisoners-of-war recaptured after escaping; all Soviet prisoners-of-war who refused to work, or were considered a bad influence on other prisoners; all Soviet prisoners-of-war screened by the Security Police (as described above); all Polish prisoners-of-war involved in sabotage. All prisoners-of-war of all nations except Britain and America, for whom a special order was made by the O.K.W.

This was called the Bullet Decree, because prisoners handed over to the Security Police and S.D. under its provisions for “special treatment” were sent to Mauthausen concentration camp and shot. As a rule the prisoners were taken directly to the “bathroom,” where they had to undress. The “bathroom” was used for gassing unwanted inmates of the concentration camp, and when there were many prisoners “for special treatment” they were gassed like so many civilians. But, as a rule, they were disposed of in what Major General Ohlendorf would doubtless have considered a more military manner. They were shot in the neck by a sort of humane killer; “the shooting took place by means of a measuring apparatus—the prisoner being backed towards a metrical measure with an automatic contraption releasing a bullet into his neck as soon as the moving plank determining his height touched the top of his head.”

British and American prisoners alone were unaffected by the Bullet Decree. But they too on occasion were liable to be “discharged from prisoner-of-war status” and handed over to the Gestapo. These included captured Commando Officers and men, who came under the provisions of the Commando Decree of October, 1942, and the fifty escapees from Stalag Luft III at Sagan, who were shot by the Gestapo on special orders from Hitler.

The notorious Commando Order was a no less blatant infringement of international law in general, and the Geneva Convention in particular, than the Bullet Decree. It was Hitler’s personal response to the inconvenience caused by British Commando raids on the Atlantic Coast, and it offers one more example of his obsession with terror as a deterrent. The gist of the matter was contained in paragraphs three and four of the original order.

“III. I therefore order that from now on all opponents engaged in so-called Commando operations in Europe or Africa, even when it is outwardly a matter of soldiers in uniform or demolition parties with or without weapons, are to be exterminated to the last man in battle or while in flight. In these cases it is immaterial whether they are landed for their operations by ship or airplane or descend by parachute. Even should these individuals, on their being discovered, make as if to surrender, all quarter is to be denied on principle.…

“IV. If individual members of such Commandos working as agents, saboteurs, etc., fall into the hands of the Wehrmacht by other means, such as through the police in any of the countries occupied by us, they are to be handed over to the S.D. immediately. It is strictly forbidden to hold them in military custody or in prisoner-of-war camps, even as a temporary measure.” Paragraph 6 showed that Hitler and Keitel were well aware of the opposition this order would arouse within the Wehrmacht.

“VI. In the case of non-compliance with this order, I shall bring to trial before a court-martial any commander or other officer who has either failed to carry out his duty in instructing the troops about this order or who has acted contrary to it.”

The only modification permitted was set out in a covering letter from the Fuehrer which stated: “… should it prove advisable to spare one or two men in the first instance for interrogation reasons, they are to be shot immediately afterwards.”

Thus from October, 1942, the Allied Commandos were up against not only the combined forces of the German Army, which was instructed to kill them to a man, but also, in the last resort, found themselves face to face with the Security Police and the S.D., whose methods we have been exploring. Sometimes they were shot on the spot; sometimes they were interrogated and then shot. Official instructions were that the cause of death should be recorded as “killed in action.” On the other hand, there is evidence that some commanders did in fact disobey the order, in spite of Hitler’s threat.

The fifty R.A.F. officers who escaped from Stalag Luft III were all said to have been shot while trying to escape. In fact, they were as a rule picked up by the Gestapo and then shot. The Security Police and the S.D. all had their orders direct from the R.S.H.A. in Berlin. One officer got as far as Alsace, across the whole width of Germany, before he was recaptured and taken to Strasbourg Gestapo H.Q. Berlin told Strasbourg what to do:

“The British prisoner-of-war who has been handed over to the Gestapo by the Strasbourg Criminal Police, by superior orders, is to be taken immediately in the direction of Breslau and to be shot en route while escaping. An undertaker is to be directed to remove the body to a crematorium and have it cremated there. The urn is to be sent to the head of the Criminal Police Headquarters R.S.H.A. The contents of this teleprint and the affair itself are to be made known only to the officials directly concerned with the carrying out of this matter, and they are to be pledged to secrecy by special handshake.…”

The procedure followed was that on the way to Natz-weiler concentration camp, where the cremation was to take place, the prisoner should be allowed to get out of the car to relieve himself, one member of his Gestapo escort was to hold him in conversation, while the other shot him from behind. This procedure was followed in other cases as well.