APPENDIX B

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE USE OF GENDERED LANGUAGE: SECTION, PARTY, AND AGE

The meaning of words cannot be categorized with scientific precision nor with the definitive accuracy of a mathematical computation. Meaning is often determined by context, and one individual’s peculiar use of words can skew the findings of a study. Nevertheless, a quantitative examination of the role of gendered terms in the Compromise debate and in the correspondence associated with it is revealing and instructive. While it lacks the definitiveness of a statistical study, it suggests a pattern of use that is consistent with the literary evidence presented in the debates themselves, and together with that evidence forms a persuasive portrait of the meaning of masculinity at midcentury. Composed of 1,721 speeches and letters, the database used in this study is substantial. Although the principle of selection could not be based on any attempt at balanced representation, every relevant manuscript collection and every speech associated with the Compromise delivered in or out of Congress that is available was examined. As a result, these sources do offer a set of important conclusions about the use of gendered language by a population of Americans concerned with sectional issues.

To be clear: this is not a statistical analysis, and in that sense is not a formal content analysis either. It does not offer systematically reproducible results and cannot, since the principle of evidence selection it employs is simply whatever is available in the historical record. What it does is present the literary evidence from the debates in quantitative form so that the meanings of masculinity can be examined from different and new perspectives. Other studies may wish to build on what this one suggests and test its findings by creating a rigorous, statistically reproducible analysis of language in this or other historical settings. The value of what is presented here lies in the new ways of viewing masculinity it advances and the new questions it raises.

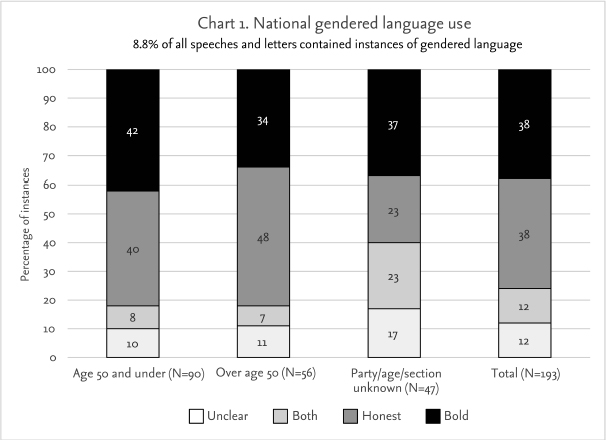

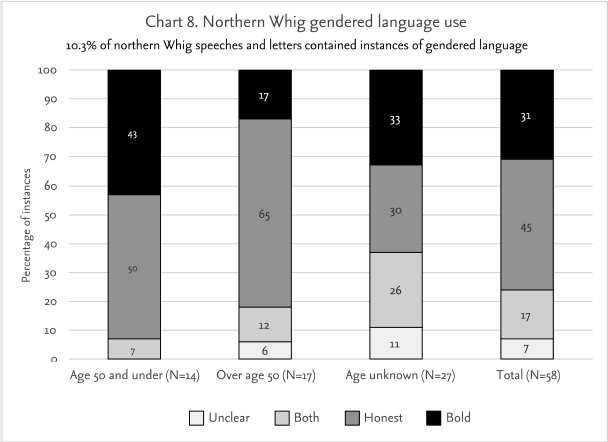

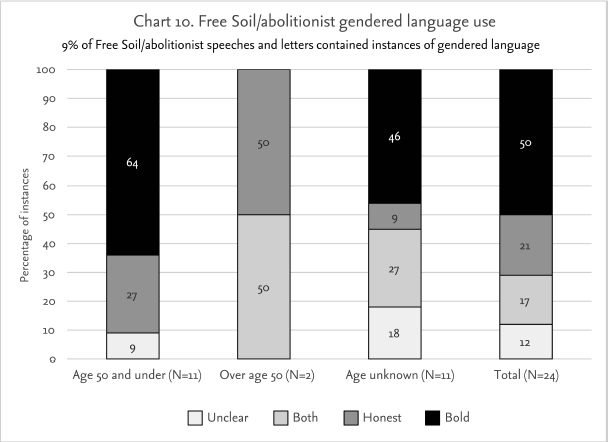

The findings of this study demonstrate that a substantial proportion (8.8%—chart 1) of all speeches and letters examined contained instances of gendered language. Northern Whigs (10.3%—chart 8) and Free Soilers (9%—chart 10) were the most likely to use gendered terms, but others employed them almost as frequently. Border-state Whigs were the single exception. They were the least likely to use them (3.5%).

The findings also shed light on the meaning Americans gave to the concept of masculinity in 1850. Just as those who have argued that the meaning was in transition would expect, among all congressmen, instances in which gendered terms meant honesty, representing the early nineteenth-century concept of restrained manhood, and instances in which they meant boldness, representing a later concept of muscular manhood, were evenly divided (38% and 38%—chart 1). And in fully 12 percent of the instances in which gendered language was used, the meaning was both bold and honest. Clearly masculinity in midcentury America had a dual meaning.1

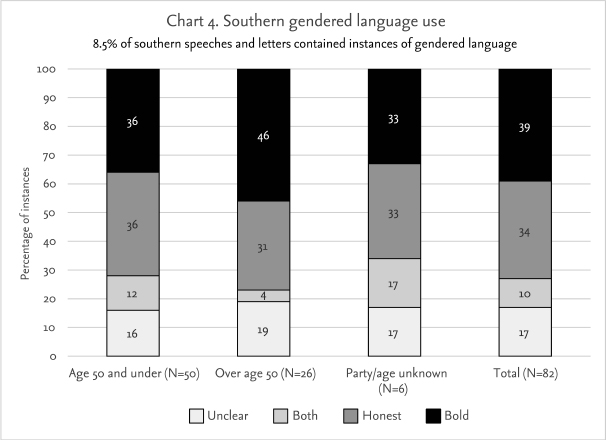

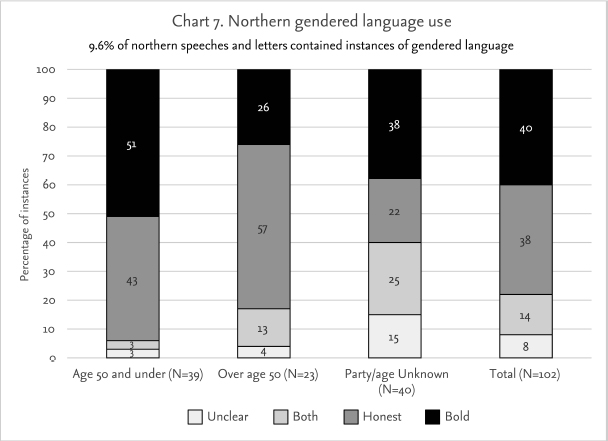

Most tellingly, northerners and southerners each divided similarly on the meaning they assigned gendered terms. Southerners gave the terms bold meanings 39 percent of the time and honest meanings 34 percent of the time (chart 4), while northerners divided 40 percent to 38 percent (chart 7). Both meanings were almost equally common in both sections. Substantial differences between the North and South over the concept of masculinity do not appear in this quantitative analysis, just as they are absent in the content of the speeches and letters examined for this study.2

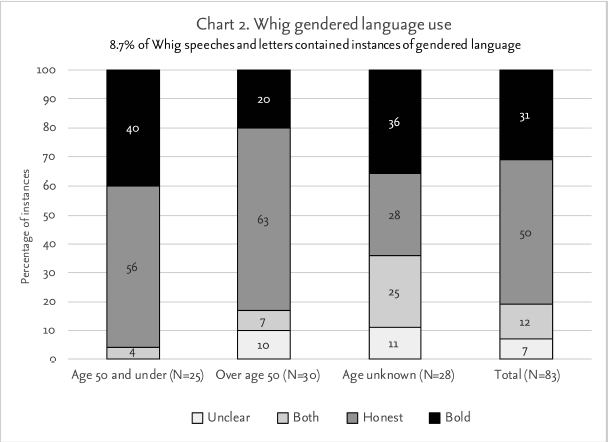

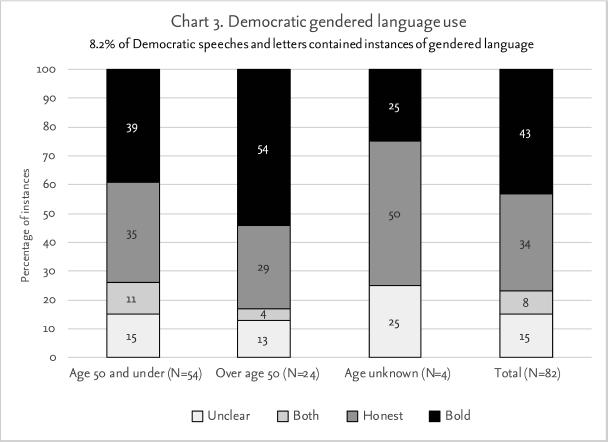

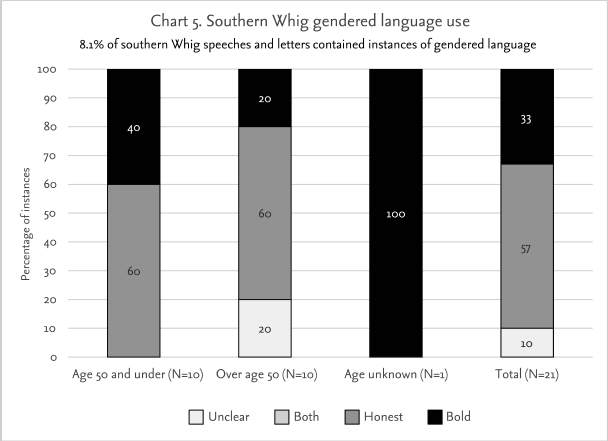

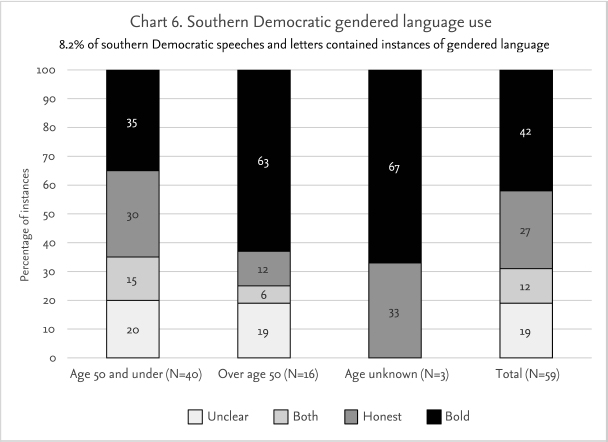

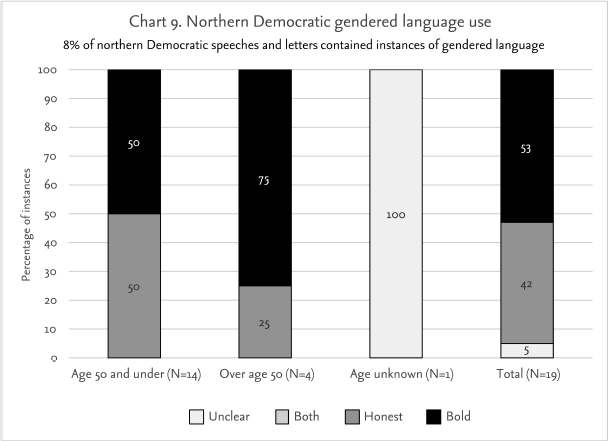

There were party differences over the meanings of gendered language, both within the sections and nationally. Northern Whigs were more likely to assign honest meanings to gendered terms (45% to 31%—chart 8), though 17 percent of the time they gave the terms both meanings. Southern Whigs, by a greater margin (57% to 33%—chart 5), favored an honest meaning when using gendered language, and nationally Whigs split 50 percent to 31 percent (chart 2) in favor of using the terms to mean honesty, while 12 percent had both meanings. Democrats broke in the opposite direction, with northern Democrats favoring boldness 53 percent to 42 percent (chart 9), and southern Democrats also favoring the meaning of bold 42 percent to 27 percent, with 12 percent meaning both honest and bold (chart 6). Combining both sections, the Democrats split was 43 percent to 34 percent in favor of the bold usage (chart 3).3

Whatever the strength of party identification in 1850, and that certainly was then and continues now to be a much-debated subject, Whigs generally favored the earlier, restrained meanings of masculinity. This should not be surprising. It has long been understood that the Whigs were the party of “moral absolutism.” The party that emphasized moral obligation and civic duties would quite naturally favor honesty and fairness as they gave meaning to gender and defined the characteristics of masculinity. Just as clear are the reasons why the Free Soilers and abolitionists heavily favored the muscular meaning of boldness (50% to 21%—chart 10) in their use of gendered words. Like Whigs, they thought in terms of moral obligation, but, as insurgents, they were always on the attack, celebrating and demanding assertiveness from their leaders and from themselves, and this was evident in the their use of gendered language.4

Finally, age also played a role in determining the meaning assigned to gendered terms. Nationally, older participants in the 1850 debate used gendered language to mean honest 48 percent of the time and bold 34 percent of the time (chart 1). In the South, that relationship was reversed across the section and among older Democrats (charts 4 and 6), but that might have been because of the impact of serial gendered language user, fifty-seven-year-old Texas Democratic senator Sam Houston, who used gendered words eight times, all to mean bold. Older southern Whigs were less likely to mean bold than honest when they used gendered language, though regardless of age, they meant honest 60 percent of the time (chart 5). Older Whigs in the North and nationally were also less likely to mean bold when they engaged in gendered language (charts 8 and 2). Older northern Democrats (chart 9) were an exception, but instances of their use were few (4), and in the North generally, the older population of participants in the controversy of 1850 favored the older interpretation of gendered meanings (57% to 26%—chart 7). The picture is somewhat mixed, with party possibly more important than age in determining usage, but age generally did influence how gendered language was used, and, as could be expected, older men were more likely to use the terms with the older meanings of honest, fair, and frank.

There were, then, variations in the meaning of gendered language in the 1850 debates. Party affiliation and to a lesser degree age played a role. But overwhelmingly, northerners and southerners understood masculinity in much the same way, and while age and party influenced usage, even in these categories both meanings were well-represented.

Assumptions

1.For the purposes of this quantitative study, gendered language includes the terms and phrases “manly,” “manliness,” “manhood,” “unmanly,” “unmanned,” “manful,” “manfully,” “as men,” “as a man,” “masculine,” “man of honor,” “like a man,” “like men,” “manlike,” “gentleman,” and “as sure as man is man.” Other terms that had a gendered meaning, such as “sickly” or “mawkish,” were not included, since they would add another layer of complexity to the analysis. Their meaning is noted and analyzed in the text.

2.In most instances, the meaning of gendered terms and phrases was clear either from associated words or from the general context in which they were used. Consistent standards of meaning were applied to determine the appropriate category in which to place each use. Language with dual meanings was placed in the “Both” category. Language with ambiguous meaning was placed in the “Unclear” category. Whenever there was the least uncertainty about the meaning of a word or phrase, it was placed in the “Unclear” category.

3.Only a very few (8) instances of gendered language use occurred among border-state congressmen. Border-state use, computed separately to test differences within the South, was therefore not shown in separate charts or included in the separately calculated southern category. However, border-state numbers are reflected in the national totals. Border states were defined as Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri.

4.Unless otherwise indicated, correspondents were assumed to be of the same party as the person with whom they corresponded.

5.Speech and letter totals count each speech and each letter as a single entry. Also counted as a single entry are both one remark and multiple remarks in a specific debate.

6.Fifty years old and under is defined as born in 1800 or after. Over fifty years old is defined as born in 1799 or before.

7.The percentage of speeches and letters in which gendered language occurred is based on the total number of speeches and letters that have at least one case of gendered language use in them (151). The percentage of use depicted in the charts is based on the total number of instances of use (193). In some cases, a speech or letter contained more than one use of gendered language. That speech or letter was counted once for the purposes of determining the percentage of speeches and letters in which gendered language use occurred, but each instance was counted to determine percentages in each category of use depicted in the charts.

8.The “Party/Age Unknown” column in charts 4 and 7 total the age unknown numbers of previous charts but add instances when the party was also unknown. The “Party/Age/Section Unknown” in chart 1 adds instances when the section was also not known.

Charts

Chart 1: National gendered language use

Chart 2: Whig gendered language use

Chart 3: Democratic gendered language use

Chart 4: Southern gendered language use

Chart 5: Southern Whig gendered language use

Chart 6: Southern Democratic gendered language use

Chart 7: Northern gendered language use

Chart 8: Northern Whig gendered language use

Chart 9: Northern Democratic gendered language use

Chart 10: Free Soil/abolitionist gendered language use