Seeing Up Close and Far Away

My grandfather always kept a magnifying glass on top of his oak dining table. That way it was immediately available when he wanted to examine the fine print in a magazine or newspaper article. Even before he gave me permission to use it, I’d had my eye on that magnifying glass. With a lens four inches in diameter, it had a brass handle discolored by age with a curious turquoise patina. Once I got the hang of how to use this bit of visual sorcery, I loved to examine the world more closely. The lens allowed me to see more detail of the material world by magnifying its complexity, bringing its little furrows, nooks, and crannies closer to me. I took the magnifying glass into all the rooms of my grandfather’s rambling Victorian house, peering at the wallpaper, examining illustrations in books, feasting on the new information I could discover in the crocheted lace curtains in the front bedroom. The world just kept expanding and increasing with detail, nuance, and a sense of depth I hadn’t realized existed.

I also loved to fool around with its weird image-distorting properties. Hold the lens with its edges toward you, I discovered, and the trees outside appear to warp. If I got my eyes right up to the surface of the glass I could make my hands into long, wavy objects through refractive sorcery. It didn’t take me long to see another magical property of perception the lens created. If you looked through it at arm’s length, it reversed the world reflected in its polished surface. The looking-glass world I glimpsed through the lens was upside-down, creating puzzling and captivating perspectives my brain loved to grapple with. The lens transformed the world into a place of enchanted impossibilities, of fictional reversals.

I no longer assumed that what I saw with my own eyes was all that was really there. The world had assumed more dimensions, and even if I didn’t call upon them all the time, I knew they were there. The magnifying lens gave me access to new realms of my imagination. As I looked I imagined new detail supporting the surface of the world. Those details encouraged my interest, and found their way into paintings I would make and stories I would write. The world was far more intriguing—and larger—than I’d realized.

Discovering the complexity of tiny intricate worlds—ones that waited only to be seen right here in the everyday world all around me—was a continuing source of adventure and inspiration. All the more so the day I put on my sixth-grade girlfriend’s glasses, looked out toward the forest, and was dazzled. “You can actually see the leaves on the trees!” I exclaimed. Pretty soon, I too was seeing all those leaves, thanks to my own pair of glasses. This experience renewed my quest to see more of the everyday world through the expanding influence of well-placed lenses.

Magnifying glasses exposed a profusion of sensory minutiae all around me. One day my eyes met a world-expanding lens that exposed the enormity of my extraterrestrial neighbors.

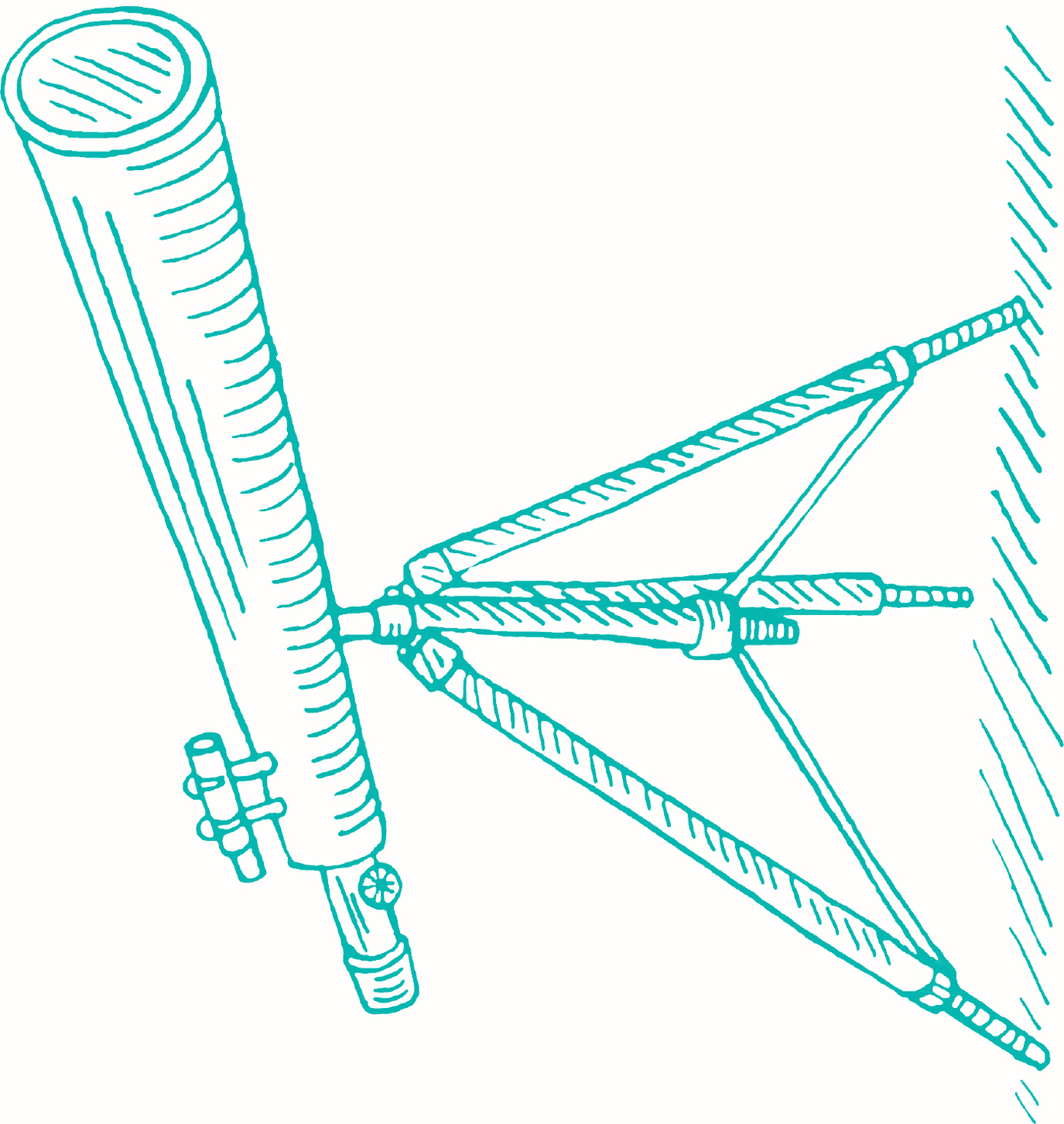

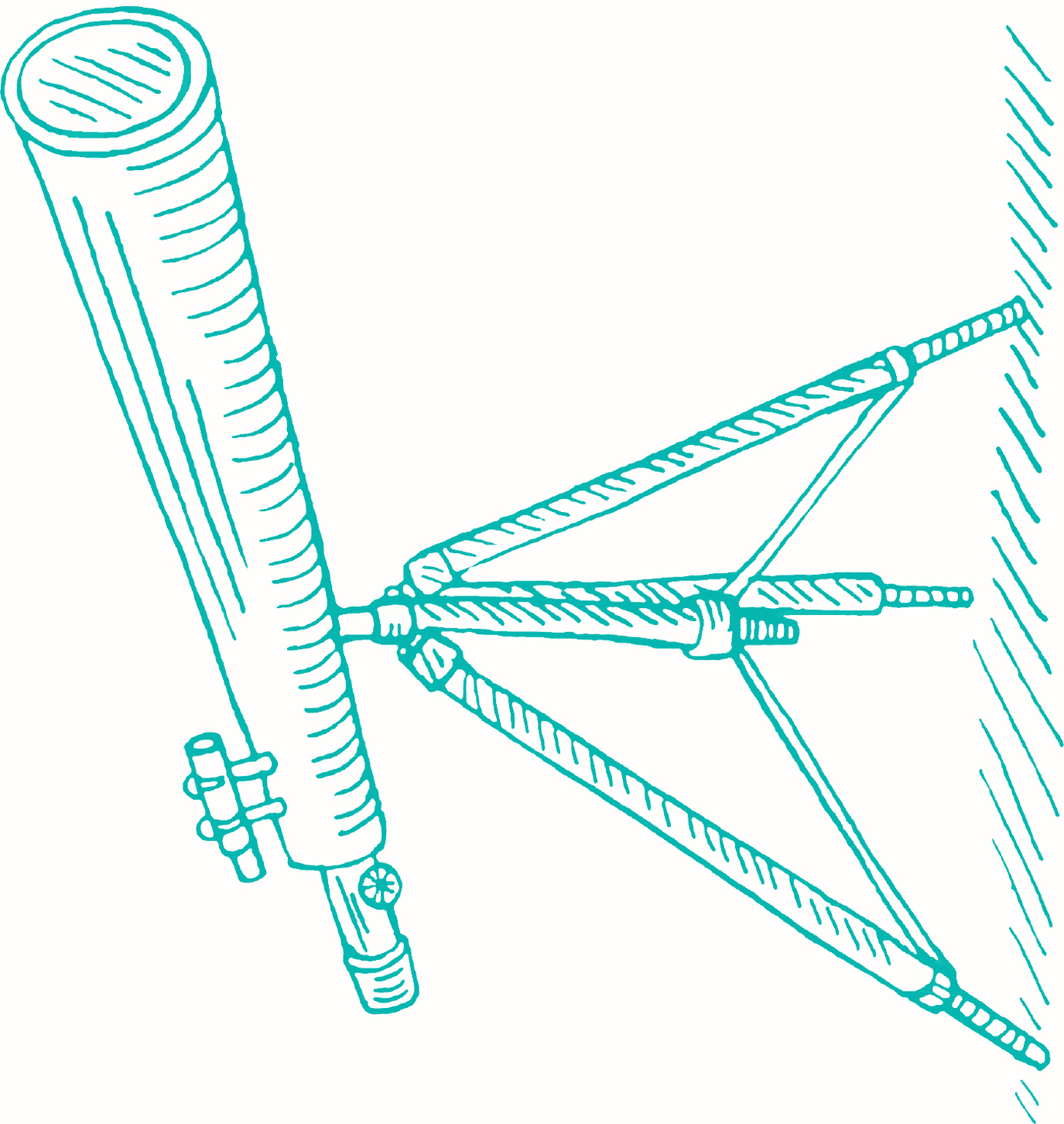

My dad’s friend Vince was the owner of a large telescope he’d built himself. A gifted host, Vince often invited his work colleague, my dad, over to visit his home in the Taunus Mountains overlooking the Rhine. Vince was a loud, rotund entrepreneur, always talking, always laughing. He must have had an interesting house and a lovely wife, but all I can remember is his role as sorcerer in my young life.

“Would you like to look through it?” he asked me one night, when my family was over at his house for dinner. He tinkered with a few knobs and buttons, tilted the large round face of the telescope toward the full moon, and invited me to look through the eyepiece.

I was enchanted by what I saw. The round white ball I had known as the moon suddenly took on a glamorous and complex persona. It had subtle tints of pink and green in what I now saw were actual valleys, mountains, and craters crisscrossing its glowing spherical face. I scanned its pale, scarred vastness, following the details to the very edge, where they seemed to fade and then dissolve into shadow. “That’s where the light of the sun is being blocked by the Earth’s shadow,” Vince explained. And with those words, the once disc-like moon expanded into a three-dimensional globe.

When I finally tore myself away from the magical scope, I looked up at the moon with my unaided eyes. There was the old familiar orb, sitting what seemed like a million miles away in a cold black sky. But I knew better. The moon was now a close friend. Vince’s telescope had brought the faraway tiny satellite up close and available for my exploration.

I always look for the moon on clear nights, admiring its saucy transformation from elegant little sliver to full-bodied sphere. I rarely look through telescopes these days, but I can still admire the shaded craters and subtle striations that are visible to the naked eye. Inside me I carry the secret knowledge of the many sensory worlds tucked inside, or soaring beyond, the immediate everyday of my senses.