Alexander Dubček looked tired as he heaved himself out of a car. He offered his sad clown’s smile and raised his hat. The leader of Czechoslovakia when the Soviet tanks rolled into Prague in August 1968 to crush his “Socialism with a human face” was back after twenty years in exile. Now it was January 1990, the Berlin Wall had fallen, and revolutions across Eastern Europe were sweeping away the fraying Soviet empire. Following the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, I was in Prague to interview Dubček, at his invitation. During his exile he had seen a film I had made, a dramatized documentary about the Soviet invasion of his country, and he wanted to meet the filmmakers, and particularly the actor who had impersonated him, Julian Glover. It was a memorable moment for me, coming face to face with the man who made the first dent in the Iron Curtain and showed the way for Gorbachev’s perestroika.

We watched my invasion film with Dubček, and he relived the terrible days when he was hauled off to Moscow to be bullied by Brezhnev and forced to abandon his liberal reforms. As our actors marched into the Kremlin confrontation—reconstructed in Liverpool Town Hall, only yards from the Cavern Club—Dubček glared at our Brezhnev lookalike and murmured, “Demagogue.”

When the screening was over, he dipped his head. Then he looked up and smiled his sad smile. “The only thing that really matters,” he said, “is that people live happy and contented lives.” It was, I thought, an unlikely, hippie-ish thought to have come from an old Communist leader, but then Dubček was never a regulation apparatchik. I remembered how he had joined the audience when the Beach Boys came to Prague in 1969, just as he was about to be sent into exile. They played “Breaking Away” for him, and it enraged the authorities.

After meeting with Dubček, I set out to find more about the rock revolution across the Soviet satellite countries of Eastern Europe in the 1970s that took its inspiration from his resistance—and from the Beatles. Czechoslovakia’s rock opposition after the Soviet invasion was led by a band called the Plastic People of the Universe. The Plastics admired the political edge of John Lennon, and refashioned Lennon’s radical notions to confront the Soviet-backed government in Prague. Their assault was uncompromising.

Throw off the horrible dictatorship!

Quick! Live! Drink! Puke! The bottle, the Beat!

The Plastic People were the vanguard for an army of rock groups across the Soviet empire in the 1970s who saw their music as a weapon to challenge the state. Many of them claimed their frustrations and their music were fueled by the Beatles, but their challenge to authority was all their own.

In East Germany, the band Renft sang about compulsory military service and the Berlin Wall. They were crushed by the state. A standoff between rock fans and police erupted on the twenty-eighth anniversary of East Germany’s foundation. Four policemen were killed and sixty-eight wounded, while unknown numbers of kids were killed, injured, and arrested. The anger of a generation raised under Communism collided with the bewildered repressions of the state—and rock music had become the battleground.

In Czechoslovakia, Dubček’s hard-line replacement, Gustáv Husák, mounted a fierce campaign against rock in the early seventies. Dozens of clubs were closed down, Western-style lyrics were banned, long hair and unconventional clothes were proscribed, decibel levels were regulated. Rock retreated to secret concerts in provincial towns and villages, but the police tracked them down. Violent battles between police and fans left dozens injured. Increasingly, the focus of official rage was the Plastic People of the Universe.

By the mid-seventies, the Plastics had turned their backs on official culture. They found a role as underground heroes, making their own sound equipment and sponsoring Festivals of the Second Culture in rural villages away from the authorities in the capital. But in March 1976, the Czech regime had had enough. The government declared that the Plastics would be put on trial. The indictment fulminated against lyrics that contained “extreme vulgarity with an anti-Socialist impact, extolling nihilism, decadence, and clericalism.” The Plastics readily accepted the charge of vulgarity, and in their defense provocatively claimed the authority of Lenin himself—who, they pointed out, had used vulgarisms in his writings.

The result was hardly in doubt. On September 24, 1976, four of the musicians received sentences from eight to eighteen months. The judge called their lyrics “filthy, obscene.” There was a torrent of protest from the West. Czech television responded by calling the Plastics “drug addicts, perverts, and devil worshippers.”

The harassment of the band members who had avoided prison, and of their fans, intensified. A concert venue was confiscated and used for target practice by the military. Another venue was boarded up and declared an epidemic site. By 1980, the assault on rock music by the Czech state had been as deadening as any of Stalin’s purges.

The rock ’n’ roll carnage of the 1970s in the Soviet satellites of Eastern Europe reached the U.S.S.R. only as the sound of distant battle somewhere over the horizon. For the masses in the Soviet heartlands, the cultural commissars delivered the safe sounds of the “vocal-instrumental” ensembles. The VIA (Vocalno-Instrumentalny Ansambl) groups with their carefully sanitized rock appeared on television and were recorded on the state record label Melodiya, their lyrics and decibel levels as meticulously regulated as the length of hair. Their song lists had to conform to quotas that dictated percentages of Soviet, East European, and Western material. The VIA songbook featured songs about grain harvests and steel output, but some of the groups became genuinely popular.

The Happy Guys were a textbook VIA group, impeccably groomed, safely rock-lite. They were allowed to tour, given a TV show, and even released robotic versions of the Beatles’ “Drive My Car” and “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” From the mid-sixties, another VIA group, the Singing Guitars, won fans across the country, featuring the safer hits of the Beatles and Cliff Richard. Their 1975 rock opera Orpheus and Eurydice gained lavish official approval. The story, of a rock star “crucified on the cross of mass culture,” was very much in line with Soviet rejection of Capitalist rock. The inevitable echo of the Who’s rock opera with its “deaf, dumb, and blind” antihero Tommy underlined the careful limits of official Soviet rock in the 1970s.

The VIAs drained much of the energy from underground Soviet rock, as exhausted musicians defected to the safety, security, and generous fees of state-approved pop. Pesniary, a VIA group from Minsk, began as another Beatles tribute band, but in the mid-seventies, they formally rejected the influence of the Beatles and soon prospered with official tours of Eastern Europe. In 1976, they were permitted to tour the United States, playing their polite and professional mix of Jethro Tull–style stadium rock and Russian folk music to polite and puzzled audiences from Virginia to Louisiana. Their manager told American reporters that “the group wholeheartedly supports the program of the Soviet Communist Party.”

One of the weirdest and most revealing episodes of this time was the story of “Mr. Tra-la-la.” Eduard Khil was a popular singer with impeccable credentials, officially named a Distinguished Artist. His style seemed guaranteed to satisfy the most suspicious censor—clean cut, smiling, a neat little triangle of perfectly folded handkerchief peeping from the pocket of his impeccable brown suit. In the early 1970s, Khil planned to record a sentimental song called “I’m Very Happy to Be Coming Home at Last” with lyrics about a lonely cowboy galloping across the prairie to his girlfriend, who is knitting socks as she waits for him. But the hints of an American setting were enough to ensure that the song was judged unacceptable by the music censors. After several revised lyrics were also banned, Khil came up with an ingenious solution. He abandoned lyrics and tra-la-la-la’ed his way wordlessly through the song in a cheerful burble. It became a huge hit and he went on performing it for twenty years, becoming famous across the Soviet Union as Mr. Tra-la-la.

Art Troitsky told me about another curious mutation of Soviet pop in the 1970s. “Most interesting and daring pop songs grew out of movies in those days,” he said. “And the biggest hit of all was a film called Diamond Hand. It was a crazy fantasy action movie, parodying the idiocies of Soviet life with several great songs.”

The seditious messages were smuggled in songs delivered by un-threatening losers, including a spiv and a drunk. “The Island of Bad Luck,” a song about a paradise where nothing works, was understood by everyone in the audience to be a wicked commentary on daily life in the Soviet Union.

“Only the censor didn’t get it,” Troitsky said. “Even better was a song about idle rabbits who didn’t care about anything. It was sung by a hopeless drunk in the film, so again the censors failed to spot the allusions to the cynical existence of millions in nineteen seventies Russia.”

The watchful pop commissars managed to domesticate some of Soviet youth’s hunger for rock during the 1970s. But on the sidewalks outside the state record stores in Moscow and Leningrad a black market in cassettes of Western albums continued to flourish. On Saturday mornings, scores of fans gathered to swap tapes and buy bootleg Beatles or Deep Purple albums. The rarest items could command a couple of weeks’ wages. In a spasm of repression reminiscent of the 1960s, vigilantes from the Komsomol youth organization mounted regular raids on the black-market gatherings, levying fines and handing out prison sentences to speculators and buyers. But the Soviet Union’s increasing openness to foreign visitors and students ensured a continuing supply of those seditious albums from the other side of the Iron Curtain.

Meanwhile a multitude of amateur bands, as many as one hundred thousand by the mid-seventies according to an official estimate, entertained crowds at state institutions playing cover versions of Western hits. Many of them delivered efficient copies of Beatles songs, but the jazz-rock group Arsenal had a huge success with a stage performance of Jesus Christ, Superstar. The state’s Melodiya label was now cashing in on the market for acceptable rock, registering nationwide hits with David Tukhmanov’s “How Beautiful Is This World” and “In the Waves of My Memory,” concept albums that blended poetry, Pink Floyd, jazz, and classical music. Melodiya also made a star of a dramatic young singer, Alla Pugacheva, who belted out her hits in a style that echoed Janis Joplin and Bette Midler. Over the next decade, the flame-haired diva would sell one hundred fifty million tapes and records, establishing a fan base on the scale of Bing Crosby or Elvis Presley.

One Western import did find favor with the nervous guardians of Soviet popular culture. Following the global success of Saturday Night Fever, disco was deemed acceptable. With its disciplined rhythms and anodyne lyrics, the dance floor was embraced as a safe place to corral youthful energies. In the mid-seventies, at a time when Melodiya had not released any Beatles album, the state label began distributing disco hits by ABBA and Soviet-bloc disco groups. Sound systems imported from the West were licensed for four hundred discos across the Soviet Union.

A visit from the German disco group Boney M in 1978 marked the climax of Soviet disco fever. The host bureaucrats of Gosconcert, the state agency arranging international cultural exchanges, had one major concern. Boney M’s biggest hit, “Rasputin,” with its refrain celebrating the czar’s evil mystic as “Russia’s greatest love machine,” was deemed unacceptable, even sixty-two years after his death. Boney M accepted the official ban on the song, but “Rasputin” continued to roar through discos across the country.

But the ultimate popular musician for Soviet-bloc audiences for twenty years from the mid-sixties was Comrade Rockstar Dean Reed. I became obsessed with Reed, and his bizarre story wove through my life as I began making documentaries in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and into the 1990s.

Trying to set up a documentary about Dean Reed became a long-running project for me. On a series of visits, I followed the story of the handsome all-American true believer from Colorado, who was recruited by bewildered Soviet culture bosses to come to Moscow as an official answer to the Beatles. Reed became a huge star across the Soviet bloc in the 1970s as the Kremlin’s official answer to the hunger for rock ’n’ roll. He looked like the answer to their dilemmas, a rocker from the West who mixed performances of “Blue Suede Shoes” and “Heartbreak Hotel” with songs about peace and solidarity. Reed saw his life as a Soviet epic, singing his song “We Are Revolutionaries” and starring in pop videos where he performed on the roof of a train blazing a new route into Siberia. He fed off the adulation of rock-starved kids, who loved him because he seemed to be the embodiment of every teenage fantasy about America. Fans mobbed him from East Berlin and Prague to Moscow and Leningrad, throwing carnations as he swiveled his hips and preached peace and love, wrapped up in sex, politics, and rock. With thick hair and a promiscuous smile, Reed was their American. I talked to a man who had been to one of Reed’s Moscow concerts in the seventies and still remembered the excitement. “He was moving, always moving, nothing like our singers. This was rock ’n’ roll. The girls were crying ‘Dean Reed, Dean Reed.’” A Soviet official told me, “With Dean, for us it was like the Beatles in England.”

Art Troitsky hated Dean Reed. “Anyone who would deep kiss with Brezhnev”—Art mimed a sloppy kiss—“was betraying everything about rock ’n’ roll.” He was plainly enraged by the memory. “Dean Reed became a huge star here. His mug was everywhere. It was even on plastic bags. He came from the land of the free and the home of the brave. And Chuck Berry,” Troitsky added. “But it was only in a place as isolated and provincial as the Soviet Union that he could have become a star.”

I had seen a preposterous video of Dean Reed, riding a unicycle as he sang “Can’t Buy Me Love.” It perfectly summed up everything Art hated, but it also radiated the charm that had made Reed a household name across the Soviet empire. It helped me to understand how this naïve and unremarkable pop hustler had managed to become a Socialist poster boy, crooning “Ghost Riders in the Sky” for Yasser Arafat, serenading the Marxist Chilean leader Salvador Allende, and delivering his starry smile for crowds of autograph hunters in Red Square. He was showered with baubles from admirers across the Eastern Bloc: the Communist Youth Gold Medal in East Germany; medallions in Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria; the Komsomol Lenin Prize in the Soviet Union. He adored the celebrity and the stardom he would never have known in the West. In the mid-seventies, he was for the Soviet masses the most famous American apart from Henry Kissinger. I could feel the overwhelming hunger among the children of Socialism for Western popular music during the cultural blockades of the 1960s and ’70s. Even the pallid version offered by Dean Reed was irresistible.

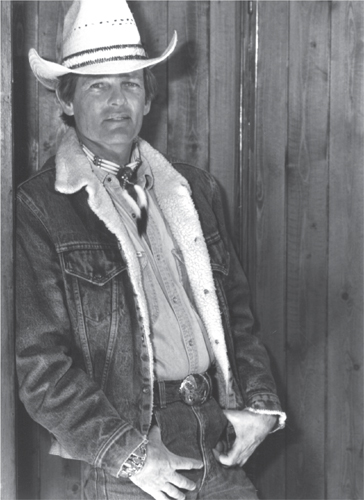

Dean Reed, all-American Comrade Rockstar.

I knew that Reed had died in mysterious circumstances in 1986, drowned in a lake behind his house in East Berlin. It made him more interesting for me, but Troitsky was unforgiving. “He was finished here anyway. We had our own rock stars by then and we didn’t need outsiders—not even Bruce Springsteen, still less Dean Reed.”

After more than twenty years of circling the Soviet Union, Dean Reed’s magic faded. The more I looked into Reed’s story, the more I understood the hopeless failure of cultural bureaucrats to provide any Soviet alternative to Western-style popular culture. Trapped inside an inflexible ideology, officials never caught up with shifting public taste. When they attempted to claim a diluted version of Western culture—as they did with Dean Reed—it was soon out of touch. I watched a grisly video of Reed trying to teach Ghostbusters dance moves to an uncomfortable group of Soviet teenagers in the final year of his life, and it stood as a monument to the bafflements of official culture. Soviet officials were always much slower than their comrades in other Eastern Bloc countries to recognize shifts in what people wanted. Long after jazz had been overtaken by rock ’n’ roll, campaigns were still being mounted against saxophones.

From the mid-seventies, there was a cautious twitching of the Iron Curtain. The Helsinki Accords of 1975 signaled improved relations between East and West. The Apollo-Soyuz joint space mission that summer provided a public relations spectacle of the new togetherness. In 1993 I met the Soviet commander of the joint mission, Alexei Leonov, who became something of a symbol for détente when he shook hands with an American astronaut in orbit. I thought Leonov, who was the first man to walk in space, was a perfect ambassador, jolly as Santa Claus. He showed me a painting he was working on to celebrate the spirit of superpower friendship. It showed Christopher Columbus’s ship on its pioneering voyage to America, and Leonov pointed to where he had inserted a badge of the Soviet space program onto the sail of the Santa Maria. Art Troitsky recalled that Apollo-Soyuz cigarettes were everywhere at the time. “It was quite a pleasant thing,” Art said, “because it seemed to be about a part-time ending of the Cold War.” Cultural exchanges were also back on the agenda for the first time in twenty years, and rock ’n’ roll was recruited to serve on the front line of détente.

Melodiya quickly made an agreement with the Beatles label in the U.K., and in 1977, Band on the Run by Paul McCartney and his group Wings arrived in state record stores. The release of a complete Beatles album was still years away, but a seven-inch disk with a few songs was permitted to trickle without publicity into stores inside a plain white cover. After the years of bootlegged X-rays and audio tapes, Beatles fans could at last buy a few real Paul McCartney tracks.

In the new spirit of careful musical diplomacy, Cliff Richard was invited to perform his safe and cheerful hits on a tour of twenty Soviet cities. A few other Western bands followed in Richard’s wake. But Elton John’s arrival in the spring of 1979 was a sensation. The culture commissars were largely untroubled by Elton’s songbook. Just one item was ruled out.

The Beatles’ “Back in the U.S.S.R.” was judged too sensitive, and for nine concerts, the hand-picked audience of Communist Party faithful applauded politely Elton John’s greatest hits—minus the forbidden song. At the very end of the final gig in Moscow, Elton exploded into the Beatles anthem. The kids stuck at the back of the hall poured past the uneasy officials to the front of the stage, cheering and screaming. Elton said it was one of the most unforgettable performances of his life—exactly the uncontrolled display of youthful enthusiasm the authorities had feared.

In fact, yet another conservative backlash against the unpredictable excesses of rock ’n’ roll was already gathering. Rumors of a Beatles reunion in Moscow had released unwelcome indications of youthful hysteria; and when a planned concert in Leningrad by Santana, the Beach Boys, and Joan Baez was canceled by authorities, the police were called in to disperse thousands of angry fans massing in front of the Winter Palace. The ensuing confrontation, including water canons and smoke grenades, became known as the Leningrad Rock Riot, and it seriously rattled the authorities. It was becoming clear that the instinctive unease inside the Kremlin about the challenge of the Beatles and rock music, which had been fermenting for more than a decade, was reaching the boiling point.

Another clash between rock fans and police in August 1979, when Aquarium played an unauthorized concert in Leningrad, resulted in police dogs, truncheons, and 150 arrests. The police accused fans of committing acts of vandalism. For authorities alarmed by the mounting disorder, it was the end of the road.

At a congress of the Soviet Composers’ Union in November 1979, in a tirade that recalled the fury of the Stalinist era, the head of the union, Tikhon Khrennikov, fulminated against rock musicians and their music. He denounced the “all-embracing permissiveness” and “vulgarity” of rock ’n’ roll. As Soviet tanks rolled into Afghanistan, a tide of repression swamped the rock scene across the Soviet Union, snuffing out the temporary truce of détente. Art Troitsky had been right about that “part-time ending of the Cold War.”