Moscow bound one more time, in 2008 I slumped in the departure lounge at Heathrow Airport, surveying the Glorious Britain Shop. Apart from Teddy bears with Union Jack waistcoats squatting on the bonnets of Mini Cooper toys, and plaques illuminated with quotations from Shakespeare, every other aspect of glorious Britain seemed to be wrapped up with the Beatles. There was a Beatles magnet set, a wash bag with Fab Four signatures, an alarm clock with Beatles faces, and a John Lennon stamp from Tajikistan framed with an old British shilling coin. So it appeared John was big in Tajikistan. At last my flight was being called.

On the plane, three excited Americans stood in the aisle chattering about financial armageddon. I heard “billions” and “Goldman Sachs.” A burly black man in horn-rimmed glasses said “Lehman Brothers gone, Morgan Stanley gone!” He seemed thrilled by the disaster movie of Global Financial Meltdown. “You watch oil!” Another man, handsome as the Pixar prince in Shrek, flaunting a gold watch the size of a fist, offered “They asked Jesse James why he robbed banks. He said ‘Cos that’s where the money is.’”

I remembered something Lennon had said as the Beatles imploded along with the hippie dream of “money can’t buy me love”: “Nothing happened, except we all grew our hair, and the Beatles made seventeen million pounds.” But even in this cold new world of grotesque money where Russian oligarchs competed to claim the biggest luxury yacht with the biggest helicopter pad, there was no getting away from the Fab Four. Channel 17 on the in-flight radio was entirely given over to Beatles songs, and the morning paper had a couple of stories about the Beatles and money. Someone was selling the drum skin from the Sgt. Pepper album cover for a hundred and fifty thousand pounds. Another woman was selling the handwritten lyrics for “Give Peace a Chance,” which had been given to her by John when she sneaked into his bed-in with Yoko. The sales room thought they should make three hundred thousand pounds. It seemed that every Beatles castoff had become a commodity, on sale in the global market place.

Art Troitsky had said I would find him at a Moscow club called Ikra, where he would be singing with Zvuki Mu. It was after midnight when I arrived, and the girl on the door was hostile. She seemed to have studied hospitality under the harridans who had chased me out of restaurants in the eighties, furious that I was interrupting their lunch break. After a while, the door girl grudgingly slouched off to check if I really was a friend of the famous Art. While I was stranded at the door I studied the unusual fish tank in the lobby. No fish, just a pink Kalashnikov nestling amid seaweed. It was, I thought, a perfect image of Moscow in the twenty-first century: Damien Hirst meets gangster chic.

The sullen girl returned and wordlessly pointed into the gloom. I fumbled my way through blacked-out rooms, occasionally glimpsing Troitsky on TV screens, mouthing silently. At last, the thumping din of Zvuki Mu guided me to another stygian room where Art was twitching on the stage, without detectable singing. A pack of women stood around on precarious heels, smoking furiously, displaying their handbags, and staring at their cell phones. They looked to be less than half the age of the guys in the band. Troitsky took time out from twitching on stage to tell me he had just been playing a corrupt plastic surgeon in a movie. “I had a red Ferrari,” he said happily. He told me I should go and meet a man called Maxim Kapitanovsky who had been making films about the Beatles in Russia. I escaped past the pink Kalashnikov, spotting a poster on the way out for a Sean Lennon gig.

It was snowing next morning, big soft flakes like artificial snow in the movie Doctor Zhivago. Instead of sleigh riding with Omar Sharif and Julie Christie, I was trudging through the streets with thousands of Moscow commuters, muffled up in identical anoraks. A torrent of cars swished through the dirty slush, and the only dash of color was an illuminated sign outside a music shop, a shining Gibson guitar. I thought of all the years when that would have been a mirage.

I waited for Maxim Kapitanovsky under the statue of a worker with a clenched fist. A plaque said this was Ernst Thälmann, a hero of East German labor. Now Ernst was guarding the door to a gigantic mall, a palace of consumerism. A stocky man in a leather jacket and a leather cap spotted me and I imagined he could be an East German Stasi cop watching over his hero’s statue. He made his way through the stream of shoppers, smiling. “Maxim,” he said. We went into the mall, past the array of cell phones and iPods, and found a coffee bar. Maxim laid a couple of DVDs on the table. I was longing to see his Beatles films, and they glowed at my elbow like smuggled nuclear isotopes. First, he wanted to tell me his story.

“We had no religion in the Soviet Union,” he began, “so we had a gap in our souls. The Beatles filled that gap.” Why did so many of the people I met want to link the Beatles to religion? It was as though the two faiths suppressed by the state, rock and Christianity, had become intertwined in a generation’s determination to free itself from the control of the state. Kapitanovsky was in a band in the seventies, playing Beatles songs and joining the rush of kids with homemade guitars. He had great stories about improvising guitar strings from the control cables for model aircraft.

Then he began to tell me about his films. “My dream was a cycle of five documentaries about the meaning of the Beatles for my generation and about rock ’n’ roll in the Soviet era. I had it all mapped out.” Five films? It sounded like a fantasy project, but Maxim said he had interested a Russian bank in backing the idea. That was of course the ultimate deal in the new Russia: Beatles, rock, and money. “Here’s how I planned it,” he went on. “Film one would be about Beatlemania in the U.S.S.R., film two—Paul McCartney’s concerts in Russia. Film three—blue jeans, the supreme objects of desire for the Beatles generation; film four, Russian rock.” He had rattled through the list with the unstoppable conviction of a producer pitching a project in Hollywood. His final episode would hardly have won over a money man doing breakfast in Beverly Hills. “My fifth film would be about restaurant musicians. All the best people played there, because they had some choice over the music.” I recalled those Soviet jazzmen of the 1930s who had flourished briefly in stylish Moscow restaurants before Stalin packed them off to his gulags. Anyway, the bank had loved it all, and Kapitanovsky had made grand plans.

“I would arrange for the Russian ambassador in London to welcome look-alikes of Paul, Ringo, Yoko, and Olivia Harrison as an introduction to the film. Then I’d interview Paul to link the cycle of films.” He said the bank adored the whole idea and wanted to take it to Putin for his support. “But then they got sidetracked in personal rivalries and the whole thing fell apart.” From what I’d heard of the murderous vendettas among Russia’s new movers and shakers, I reckoned he was probably lucky not to have finished up at the bottom of the Moscow River.

He got more coffees for us. “Anyway,” he said, “I managed to make two of the films—Soviet Beatlemania and McCartney’s visit. The McCartney film ‘Seventy-three Hours in Russia’ was a nightmare.” Maxim had my sympathy. The prospect of finding a way through the combined obstructions of Russian security goons and Paul’s superstar minders would, I imagined, have taxed the ingenuity of a Mossad hit squad. Kapitanovsky’s own ingenuity in pursuit of McCartney was impressive. “When Paul was in Saint Petersburg, it was almost impossible to get anywhere near him. Then I found some guys who were just dismantling a huge crane near his hotel, and I persuaded them to rebuild it so we could get high shots of Paul’s comings and goings.” In Moscow, Kapitanovsky snooped footage of rehearsals for the Red Square concert during guerrilla warfare with McCartney’s seventy-strong security force. “One of his bodyguards smashed our camera, but it made a good moment for our film.” He said his Beatlemania film, titled The Beatles Are to Blame, got shown repeatedly on Russian television, but 73 Hours with Paul McCartney “just won bits of paper at Russian documentary festivals.”

Kapitanovsky walked me through a blizzard to the Metro station, and I trundled back to the city center. It was still snowing on Tverskaya Street near the Kremlin, and the old beggar woman was still kneeling in the snow under posters for concerts by Boris Grebenshikov, the Animals, and Charles Aznavour. I gave her some rubles and plodded to my hotel. Up in my room, a maid vacuumed around me as I viewed Kapitanovsky’s DVDs. The “Beatlemania” film was fun, stuffed with crazy archive footage of bald apparatchiks trying out Beatles wigs and rock fans being rounded up by vigilantes. 73 Hours with Paul McCartney looked as grueling as Maxim had suggested. It seemed mainly to be made up of Paul and Heather—Mrs., soon to be ex, McCartney—getting in and out of stretch limousines surrounded by human shields of security. There was affecting footage of fans, including the inevitable Kolya Vasin—waiting for a Beatle. “It is real Beatle?” asked an ecstatic grandmother. A banner proclaimed, one sweet dream came true today. There was a memorable shot of McCartney’s limo racing past, Paul sticking his ever-perky thumb out of a window to make a perfect snapshot of superstar detachment. There was lots of footage of people shining floors, arranging flowers, and painting drainpipes in preparation for the arrival of Sir Paul. They would have made less fuss, I reckon, for Queen Elizabeth. Kapitanovsky’s high shots from the reconstructed crane looked nice, and I enjoyed the tussle with McCartney’s security squad in Red Square. Best of all was a delicious fantasy filmed during the sound check: Lenin and Marx look-alikes bopping together.

The room maid completed her cleaning marathon and headed for the door. Before she left, she turned and said shyly, “I love Bitles.”

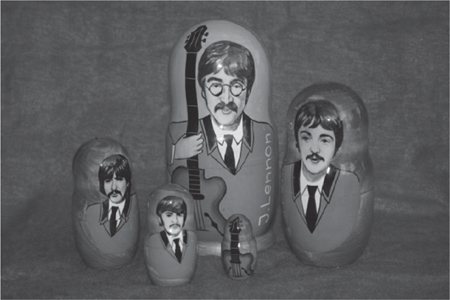

It had stopped snowing at last, and I walked across to Red Square. On the way, I stopped at one of the stands where hustlers try to push Communist kitsch—KGB badges, Red Army hats, Stalin T-shirts. I surveyed the armies of matrioshki, the nests of dolls that have become favored weapons in the arsenal of junk aimed at tourists. The Great Dictators (Genghis Khan inside Hitler, inside Stalin, inside Mao, inside Saddam Hussein) were lined up next to Harry Potter (containing the usual suspects). Then I spotted a Beatles set. John—clutching a guitar, circa 1966—was the container for the rest of the Fab Four. It was not his best look, regrettable slug mustache, dreary gray jacket with velvet collar; inside him was Paul, same bad mustache, same gray jacket, not even provided with a guitar; inside Paul, George, ditto mustache and jacket; inside George, Ringo—unrecognizable; and inside Ringo, a tiny guitar—presumably misplaced by Paul or George. I bought the Beatles and walked into the square.

Near Lenin’s tomb, an old woman was selling postcards. She crouched on a stool, while a familiar voice spilled out of her battered tape recorder. After a moment I recognized the singer; it had to be Joseph Kobzon. The inevitable Kobzon has followed me over the years, wherever I’ve gone in this part of the world. I always thought that if Brezhnev could sing, he’d sound like this. Kobzon the rousing tenor who became the most-awarded artist in Soviet history; Kobzon belting out patriotic ballads and heroic anthems, a favorite of the Kremlin and the inescapable performer at every state occasion for thirty years. I remembered Kobzon for a couple of reasons: first there was his disastrous wig; more surprising, his story sometimes seemed to parallel and mirror the Beatles.

Beatles matrioshki dolls, on sale near Red Square.

Kobzon’s first album was released in 1962, like his Liverpool doppelgängers. His breakthrough came in 1964, as the Fab Four were sweeping the Soviet Union. And although Kobzon was awarded “People’s Artist of the U.S.S.R.,” he was something of a rebel. While Lennon handed back his medal presented by the queen of England to protest the Vietnam War, Kobzon—who is Jewish—had outraged the Kremlin by performing Jewish songs in support of Israel. He had been expelled from the Communist Party for that gesture, though he was later rehabilitated. Kobzon then became the first celebrity to perform in Chernobyl and risked his life as the key negotiator in rescuing hostages during a terrorist siege. After the collapse of Communism, Kobzon was sometimes called “Russia’s Frank Sinatra” because of his contacts with the Moscow mafia. He insisted that as a popular entertainer, the contacts were unavoidable, but the allegations cost him an American visa. His concert tours of South America, Africa, and Europe continued, and he has become a deputy in the Russian parliament. Recently, I had heard that Kobzon and the Beatles had finally converged. The ultimate official singer had made a pilgrimage to Liverpool, and then starred in a Russian celebration of Beatles music that climaxed with Kobzon’s rousing performance of “Hey Jude.”

The old woman packed up her postcards and tape recorder, and I spotted a group of American tourists on their way to visit Lenin’s tomb. Their guide, a sharp-featured little woman with the people skills of a gulag wardress, was clearly finding her flock unsatisfactory. “Please pay attention, dear visitors,” she shrilled. She told the group she was the same height as Lenin, and they should know his hair and fingernails were still growing. Someone tried to ask her a question, but she brushed it aside. “At the appropriate point,” she barked. She had important facts to deliver. “Lenin is not a wax figure, like Mao Tse Tung.” The war of the embalmed leaders was not getting through to the tourists. They shivered, clearly looking forward to taking refuge for a while with Lenin and his fingernails in the tomb. Then the guide spotted me. “Go away! Do not listen! This is private party!”

I headed across the square to look for the restaurant where I was due to meet Art Troitsky. It was getting dark now, and the golden domes of the Kremlin were illuminated, magical in the dusk. The red star on the top of a Kremlin tower that had somehow been spared the mass execution of most statues and symbols of the Soviet era was glowing like a beacon. A black limo sped out of the Kremlin gate and headed for home. In the space in front of Saint Basil’s cathedral where Paul McCartney had played “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and thrilled thousands to tears, a handful of kids were laughing and circling around on their mountain bikes, crunching over the frozen snow. A boy in a bright yellow anorak came to a halt when he spotted the Beatles matrioshki I was carrying. “Beatles forever!” he shouted.

I found Troitsky in a restaurant called Chlam, a stylish construct of distressed brick with Chet Baker whispering from concealed speakers. I thought how these restaurants had become showcases of the new Russia, dizzyingly expensive, with the life expectancy of a journalist investigating a gangster businessman. “Chlam” meant “trash,” and the place was virtually deserted. “I love Chet Baker,” Art said, giving me a hug. He spotted my Beatles matrioshki, and we agreed that the doll-makers could have chosen to celebrate the lads at a time when they’d abandoned the slug mustaches. We munched steaks as costly as gold bars, and Chet drifted into another smoldering ballad. I asked Troitsky if the Beatles were effective as aids to seduction. “Oh, I think everyone of my age in the Soviet Union would agree their music had huge sentimental value. Every Russian teenager met his first date and had his first kisses to a Beatles soundtrack. And now when they hear ‘Yesterday’ I’m sure they have beautiful memories of things that will never happen again.” The thought stirred some memories of his own. His marriage to Svetlana had ended years earlier, and I knew he had four children with four different women. “I’m a spoiled boy,” he said cheerfully.

I told him I had watched Maxim Kapitanovsky’s film about Beatlemania and had been struck by the old archive film of kids being rounded up by vigilantes for buying rock records. “As I told you once, we were living in a monster state. If you really want to get a glimpse of those crazy times, I hear the KGB has opened a museum. Everybody is a businessman these days.” I said I’d check it out, and as Chet sang “Let’s Get Lost,” we toasted the KGB.

“I love the Beatles,” said Vera, my tour guide as we walked past the old KGB headquarters, which had been the focus of nightmares for generations of Soviet citizens. “I still listen to ‘Girl’ and ‘Yesterday’ and all those pretty songs,” she recalled, and she sang a snatch of her favorite: “I believe in yesterday …” The vast yellow KGB citadel, known as the Lubyanka, looked almost benign in morning sunshine, but for a woman of Vera’s generation it was still a fearsome place. A statue of Feliks Dzerzhinsky, the murderous head of the Bolshevik secret police, used to stand in front of the building, but it had been hanged from a crane and hauled away by demonstrators in 1991. The plinth was still there, like a ghoulish warning that Stalin’s “devout knight of the proletariat” hadn’t really gone. It reminded me of the photographs that had been doctored during the Great Terror. In some, Trotsky had been painted out but his boots had been left in, to remind any supporters about the dangers of opposing the dictator.

Vera found the door to the KGB museum, tucked away on a side street. She said the place had been set up in 1984 to train young agents in the best traditions of the security services, and had opened to the public more recently. We were greeted by a cheery little KGB colonel in a suit, who promptly sold me a badge for the FSB, the KGB’s successors—“same studio, different head,” Art Troitsky had said.

The museum was chilling. Like the Stasi secret police museum I had visited in East Berlin, it was a frozen record of a hellish state ruled by madness and paranoia. Here was a letter written in blood by a KGB prisoner, there a wreath for Dzerzhinsky’s funeral made entirely from bullets. I peered at crazed spy techniques, microdots buried in newspapers and bibles, and at lunatic killing devices: walking-stick swords, poisoned spectacles. I couldn’t find anything to match the Stasi’s more fiendish relics: jars to preserve the scents of dissidents so the dogs could hunt them down (dogs that had had their voice boxes amputated). But that was perhaps because the KGB museum was mainly a monument to the evils of the Cold War enemy in America, and skipped over decades of home-grown horror. There was a conspicuous absence of more recent KGB heroes, from Andropov to Putin. No wonder, I thought, Kolya Vasin exiled himself in his apartment and defected with his beloved Beatles music.

On the street again, Vera told me she was a passionate democrat: “Just two percent of people think like me.” And she had a sobering story. “Just the other day a honeymoon couple asked me to take them on a tour of Stalin’s Moscow. They especially wanted to see the House on the Embankment where top officials lived and from where they were regularly seized and executed.”

In a kiosk on the street, I found a Russian magazine called “A Hundred Men Who Changed the Course of History.” The issue was devoted to the Beatles. On page eight, there was a still from my film in the Cavern Club. A feature told how the lads had fought for peace, and against the Vietnam War. In the back of the magazine was a section about celebrities who featured in the Beatles story: the Stones, Andy Warhol, Mia Farrow, and … the British queen, Elizabeth the Second. She made it on the basis of having awarded those Member of the British Empire medals to each of the Fab Four in 1965. Inevitably, the magazine recorded how John handed back his medal as an antiwar protest. It was some sort of confirmation that Lennon, who had once been a target for extermination as one of “the Bugs,” was now revered as a heroic fighter for peace—and a man who “changed the course of history.”