THIRTEEN

THE JESUS-AS-CHRIST MYSTERY

It has already been mentioned that the Trans-Himalayan Adept Brotherhood rejects the idea of the Christian figure of Jesus as having been a historical figure at the time suggested by the New Testament—which was written some several decades at least after that. It also seemingly rejects the idea that he was “Christed.”1 We otherwise know for a fact that the well-known Jewish historical figure of Philo (ca. 30 BCE–40 CE)—sometimes known as “Philo the Alexandrian”—who was a contemporary of the supposedly biblical Jesus, mentions him not at all, in any context. The slightly later Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (ca. 37–101 CE) does mention him, however, in his work Antiquities of the Jews, referring to him rather obscurely as having been “a wise man” and “a doer of [unspecified] wonderful works” who was “believed by some to be the Christ.”2 Yet it is noteworthy that Josephus gives no indication at all of how long before his own time Jesus had lived—which (added to the title of his book) suggests that it cannot have been that recent—although he does add the (by then self-evidently secondhand) story that he had been condemned to death by Pontius Pilate.

Historical details about the character of Pilate—known as the fifth Roman prefect of the province of Judea between 26–36 CE as the New Testament describes—are themselves very conflicting. They have thus given much rise to doubt about his actual existence and involvement in the events leading to the crucifixion of Jesus, as described in the New Testament. From the associated timeline—if he did exist—it would appear that Jesus must have lived during the first quarter of the first century CE. However, the historical reports by both Philo and Josephus come nowhere near confirming this. That in turn suggests that the story may perhaps have involved a historical combination of two individuals brought within the one “Jesus” figure, either through ignorance or through deliberate manipulation. Which is wholly unclear. But the modern Tibetan Adept DK refers quite openly to “the initiate Jesus” (in the books of A. A. Bailey), ratifying the tradition of his teaching and that his body was both temporarily “overshadowed” (or rather, temporarily informed) by the Lord Maitreya, the seemingly true Christ, and then later crucified.3 Where then lies the actual truth?

When we look at the known history of the early Church, it becomes clear that the Christians were persecuted until 313 CE when the Emperor Constantine (289–337 CE) issued an edict to halt such activities, although Christianity did not formally become the acknowledged main religion of the Roman Empire until later in that century. But, most interestingly, forms of Christianity—apparently of a decidedly gnostic leaning—had already existed in the first two to three centuries BCE. It was then that an association with the impending astrological era of the fish (Pisces) was attached, to confirm that this new Mystery tradition was intended as being separate from the passing zodiacal era of the Ram (Aries), the latter having a predominantly Egyptian association. This is somewhat comparable to our today looking forward with eager anticipation to the impending Age of Aquarius, thereby readying ourselves for its influence. So, in order to see if we can deduce anything further, let us look at the early history of the Middle East area in brief outline, paying particular attention to the first few centuries BCE.

To begin with, ancient Palestine prior to the eighth century BCE consisted of three minor kingdoms: Samaria in the north, Galilee in the center, and Judea in the south. Of these, Samaria was the most cosmopolitan and wealthy because of its sea trade via the Mediterranean ports of Tyre and Sidon in particular. Inland Judea (containing Jerusalem) was of very minor political significance. However, in about 725 BCE, the Assyrian empire invaded the area, en route to conquering Egypt, and annexed it. Not surprisingly perhaps, most of the native peoples of Galilee and Judea were duly taken as slaves and assimilated into the northern Assyrian empire where they eventually became citizens. Although the Egyptian empire recaptured Palestine briefly for a few decades from about 612 BCE, the Assyrians were soon after defeated by the far more powerful Babylonian empire and Palestine was then annexed by it under the overall rulership of King Nebuchadnezzar. He—so the Old Testament tells us—destroyed the first temple of the Hebrews, supposedly built by Solomon some four hundred years before, although Solomon’s actual existence has never been proved and, from the esoteric viewpoint, looks to be little more than another biblical allegory.

The Babylonians were then overthrown in turn by the Achamaenid Persians under Cyrus the Great (559–530 BCE) (see fig. 13.1), who allowed those Judeans who desired it to return to Judea, commencing about 538 BCE. The “second” temple in Jerusalem—the remains of which still exist today—was (according to tradition) then built, apparently during the reign of the Persian emperor Darius, and completed about 515 BCE. The later Persian king Artaxerxes then allowed the Hebrew prophet Ezra to return from Babylon to Judea in about 460 BCE, specifically to set up a colony with his particular monotheistic sect, whose intention was to pursue the idea of the “return to Zion” that has been at the center of the Jewish faith ever since. However, the name Zion is itself clearly derived from the Sanskrit dhyan (dhzyan in the Tibetan), which, as we saw in earlier chapters, is associated with the divine state of the heavenly world, not at all with the material one. The (allegorical) teachings of Ezra thus seem to have been derived from the Ancient Wisdom philosophy. They were learned from the Babylonians or Persians and not from a Jewish source, even though subsequently (mis-) interpreted and promulgated by the teachers of later Jewish religion, the Pharisees, the precursors of the rabbinate. However, somewhere along the line, these same teachings diverged from spiritual allegory and sacred metaphor into the distinctively territorial viewpoint prevalent today.

Fig. 13.1. Cyrus the Great

In 323 BCE Alexander the Great died, having already conquered the Persian empire. His own empire was then split between his three main generals, the Ptolemies taking Egypt and all the lands that had comprised ancient Palestine, up to the southern borders of modern Syria and Lebanon (the latter being associated with Phoenicia). The Seleucids then took over the lands comprising what is now modern Turkey and Syria, extending all the way to India. However, in about 200 BCE, the Seleucid empire (which contained ancient Babylonia) conquered Palestine and annexed it. At about the same time, the codification of Jewish law (in the Mishnah) followed in both Palestine and Babylonia, in the latter of which large numbers of Jews still lived.

By then two Jewish sects had appeared in Jerusalem—the Sadducees (comprising the upper, wealthier classes and priests who claimed major control over the temple and insisted on literal interpretation of the law) and the Pharisees. The name of the latter is derived from the Hebrew perushim, itself derived from the Sanskrit purusha, meaning “pure spirit”—the sixth element, above even the aether4 (thus separate from all matter). Their single aim—in line with their name—seems to have been associated with cleanliness and purity in all respects of life (as with modern “orthodox” Judaism), although their approach to the interpretation of the law was rather more flexible.

Only thirty-five years later, the Judeans liberated themselves from Seleucid rule and formed their own Hasmonean dynasty of kings, which subsequently captured Samaria and thus reunited ancient Palestine. From about this time, Jewish theological orthodoxy centered on the temple in Jerusalem seems to have hardened and become much more separatively nationalistic. During all this time, however, Greek cultural and spiritual influence (not that of the Jews) was paramount throughout the whole area of the Middle East in general. This is notwithstanding the fact that many Jews had held influential public positions throughout Babylonia and Assyria for several centuries (as they did later in Rome). It is conjecturally in memory of this association with their time in Babylon (which was not a “captivity” at all in real terms) that the male Hasidic Jews of today still wear their side hair in long ringlets, evidently copying the Babylonian fashion of that time with the whole head of hair.

The Roman empire then invaded Palestine during the first century BCE, its general Pompey capturing Jerusalem in 63 BCE and transforming the area into a Roman protectorate. Then in 31 BCE, the emperor Octavian (later Augustus Caesar), en route to reconquering Egypt (which became a province of the Roman Empire in 30 BCE), put Samaria under the rule of Herod the Great, the then king of Judea. The Romans later annexed the whole area of Palestine as a province in 4 BCE upon the death of Herod—which is how, shortly after, we later find the figure of Pontius Pilate supposedly coming on to the scene. There subsequently followed the Jewish Wars of Hebrew nationalists against the Romans, led latterly by the Zealots who took over Jerusalem in 65 CE. They were, however, defeated by the Roman generals (later emperors) Vespasian and Titus, who had the Jerusalem temple destroyed in 70 CE—which effectively put an end to the existence of the Sadducees. It seems to have been from then that the main Jewish diaspora commenced and the pharisaic rabbis progressively set up their widely scattered system of synagogues.

THE BREAKUP OF THE GREEK MYSTERY SCHOOLS

Returning to our main theme, however, and going back a couple of centuries (to the time of the Macedonian Alexander the Great), we should note that with the progressive break up of the state-governed Mystery Schools of the Greek polis, two separate schools had appeared in their place, as we saw earlier. These were those of the “craftsmen” on the one hand, the artisan school, originators of the Assyrian Dionysii and the much later medieval European guilds, including the Masons. On the other was that of the “gnostics” (the knowledge school).5 Prior to their dissolution, all esoteric knowledge and craftsmanship had been learned in the Mystery Schools, following a triple developmental progression (usually involving a seven-year period of neophyteship), which clearly parallels the seven-year apprenticeship of original Craft Masonry, before the birth of Freemasonry.

So Greek gnosticism was itself a twin, born of a deceased parent; for some reason or other (possibly through Adept influence), it found a foster home in the internationally accessible city port of Egyptian Alexandria. It is worth mentioning in passing here that Jewish kabbalistic gnosticism, derived from the Hebrews’ time in Babylon, seems to have settled and initially developed in Ephesus6 (on the western coast of modern Turkey). It did not, at that time, have any apparent interest in influencing or uniting with the mainstream Jewish theology being developed by the Pharisees in Palestine. That itself is suggestive of the fact that early kabbalism did not see Jewish “orthodoxy” as being worth any real degree of association.

THE ESSENES AND THE EGYPTIAN RELIGION OF SERAPIS

As already indicated, ancient Alexandria became a real philosophical and religious “melting pot” within half a century after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE. The Ptolemy family successor—as head of the Egyptian part of Alexander’s empire (extending from Egypt into the Levant)—was Ptolemy Philadelphus (309–246 BCE) (see fig. 13.2), who set about the reformulation of a modernized and broader based Greco-Egyptian religion. This was that of Serapis, the Greek form of the dual Egyptian As’r-Hpi (i.e., Osiris, the god of the Nile), a cult that was flexible enough to absorb other esoteric belief systems (including those of neo-Platonists and neo-Pythagoreans) in such a manner as to cause as little potential social friction as possible in cosmopolitan Alexandria. Ptolemy even treated diplomatically with the Indian emperor Asoka to allow the promulgation of Buddhist teachings in his kingdom. It was as a result of this that there appeared the characteristically gentle but ascetic belief system promulgated by the Essenes, one of the early gnostic sects, which seems to have commenced its existence in Alexandria itself as the Therapeutai and later spread to Palestine and Syria.7

Fig. 13.2. Ptolemy Philadelphus

The Essenes were a determinedly occult group whose overriding characteristics involved deep humility and an ascetic contempt for worldly goods, in conjunction with total philanthropy toward others (even non-Essenes). Their primary concerns seem to have lain with harmlessness to all others and to psychological and even physical purity as a sign of holiness. Their central aim in life was consequently that of becoming the literal temple of the Holy Spirit and thus, effectively, a prophet.8 Healing and magic were arts pursued by them. It is suggested by some historians, however, that the study of logic and metaphysics (presumably in the Greek style) was regarded by the Essenes as injurious to a life of devotion, although it is acknowledged that they were deeply concerned with understanding the nature and organization of the angelic worlds plus the origin of the soul and its relationship with the body.9 Their religious observance—involving a perfect maximum of ten people—was that of uttermost devotion to the demiurgic Deity whose objective symbol (the Sun) they venerated.10 This concern with the decad and many of their other practices have been seen by many (but not by some overtly nationalistic Jewish historians) as Pythagorean in nature.

THE NAZARENES AND THE PHARISEES

It would appear that the overall Essene community was formed of two groups. One, completely monastic in nature and comprising only menfolk (women not being admitted), involved a mystic and occult brotherhood. To enter this brotherhood, the aspirant had to wait outside it for three years, in a testing manner distinctively reminiscent of the Pythagorean and Stoic brotherhoods. The other Essene group—which one would imagine to have been by far the larger—comprised a community of married men and women plus their children.11 One of the original Essene offshoots is now known to have settled in a community adjacent to the Dead Sea, where they later came to be recognized as the long-haired “Nazaars” or “Nazarenes.” Here the latter remained in existence for several hundred years, hence their association by some with supposedly Jewish origins, particularly as the Judaic Pharisees seem to have adopted many of their doctrinal and practical rituals, especially those associated with extreme subjective and objective purity and cleanliness.

In that regard it was suggested a few pages earlier that the name Pharisee seems quite likely to have derived from the Sanskrit purusha, thus implying a state of development “above even the spiritual quintessence.” Purusha is also to be found in the Greek as parousia—hence the Parousi, thus suggesting an Indo-Persian (i.e., Parsi or Zoroastrian) origin; hence perhaps the common veneration of the Sun. Despite this, the Nazaars seem to have been preceded locally by the Ebionites, who were the earliest sect of Jewish “Christians,” even well before the term “Christian” had come into use,12 as also described a little earlier.

The variety of other influences available and in widespread use at this time is notable. Clement of Alexandria confirmed that the initiates of Serapis wore on their persons the sacred name IAO (probably derived, again through phonetic corruption, as Yahu from the Babylonian god EA, i.e., as Ea-hu), apparently in conjunction with the Vesica Piscis. This was itself regarded by esotericists of the time (neo-Pythagorean geometricians in particular) as the determinant of all dimensions.13 It is also recorded that the early Christians used the Tau cross on their tombs,14 which—by virtue of its origin in China—gives us a clear indication as to just how culturally cosmopolitan ancient Alexandria was. There is otherwise known to historians a very interesting and informative letter of 118 AD from the Roman emperor Hadrian to the consul Servianus confirming: “They who worship Serapis are Christians and such as are devoted to Serapis call themselves Bishops of Christ.”15

Blavatsky otherwise confirms for us that the gnostic Nazarenes were the original Christians and opponents of the later ones.16 This is further amplified by bishop Eusebius, one of those later and decidedly political Christians who battled so hard and so ruthlessly against the Alexandrian gnostics, neo-Pythagoreans, and neo-Platonists. He commented about the Nazarenes: “Their doctrines are to be found among none but in the religion of the Christians according to the Gospel. . . . It is highly probable that the ancient Commentaries which they have [the Dead Sea scrolls and Pistis Sophia among them perhaps?] are the very writings of the Apostles.”17 No subsequent attempt to verify this more clearly seems to have been made, however.

By virtue of Pythagoras, Plato, and a host of other well-known Greek philosophers having spent their educationally formative years in Egypt, at a time when the Greek Mystery traditions were disintegrating and falling out of public favor, it is not surprising that so many Greeks and others of a philosophical or mystical nature gravitated toward Egypt, doubtless hoping that a completely new Mystery Religion would become apparent. As the historian David Fideler remarks:

There can be little doubt that, among the initiates of the early Church, Christianity was seen—and consciously developed—as a reformation of the early Mysteries. . . . It is also clear that behind the scenes of the early Christian movement there existed an unknown number of enlightened scholars who were attempting to take the best elements of Jewish, Greek and Egyptian spirituality and synthesise them into a new universal expression. Exactly who these individuals were, however, we do not know.18

As regards the adapted Mysteries themselves, the mystic grades in the formative Church (these being derived from the Egyptian rites of Serapis in Alexandria) were as earlier described in chapter six.19

THE FORMATION OF THE EARLIEST CHURCH

At this point we might pause a moment to indulge in a little logical speculation concerning the social mix of Alexandria and its development, based upon an understanding of ordinary human interrelationships. To begin with there would have been the upper classes, mainly of Greek descent from Alexander’s military officers, mixed with the higher Egyptian priesthood and the national aristocracy. Many from the latter would have comprised a semi-intellectual elite, due to the considerable range of academic study pursued by the Egyptian priesthood. As mentioned earlier, their academic study was based on the forty-two sacred Books of Tehuti, which would almost inevitably have been intellectually orientated (although full also of sacred metaphor plus metaphysical allegory), and thus quite definitely aimed toward esoteric interpretation. Secondly, there would have been the local merchant, artisan, and farming classes, much more naturally orientated toward the merely devotional and literalistic approach to religion and life in general, as is indeed the case even today, all around the world.

However, not all esotericists of the time would necessarily have opted for wholesale attachment to the merely devotional approach of the state Serapean religion. The neo-Pythagoreans, Stoics, and neo-Platonists are highly unlikely to have done so. They were spiritual purists and would probably have remained more self-evidently objective and intellectually detached in their approach. That in itself could well have led to an increasingly self-evident socio-religious split, resulting in the most mystically inclined (i.e., the “New Age” Therapeutai-Essenes, with their decidedly neo-Pythagorean and Buddhist inclinations) leaving the urban environment of Alexandria altogether, to migrate elsewhere to the “wide open spaces” of other parts of the Middle East, like Qumran and Nag Hammadi. But this separation was to continue. As Blavatsky comments, “When the metaphysical conceptions of the gnostics [i.e., the true esotericists] began to gain ground, the earliest Christians separated from the Nazarenes.”20

Of those who preferred to stay in Alexandria, the more gregarious devotional types (the local merchant and artisan classes particularly) would almost certainly have come to see themselves as socially distinct from the rest and would thus have gradually evolved a more politically formal approach to their religious beliefs, thereby leading to the separate establishment of the early Christian Church. They would then have found themselves in direct confrontation with the gnostically orientated intelligentsia of the upper classes over particular religious issues. It is this perhaps that led to the first burning of the great Library of Wisdom in Alexandria by a politically inflamed Christian mob, akin to the one that murdered and dismembered the female philosopher Hypatia.

Intellectual and upper class elites of any age or era have always tended to suffer from a degree of arrogance, often involving a “looking down” on those of lesser intellectual depth and breadth, not able to comprehend the more subtle aspects of life because more concerned with the business of earning a living. Correspondingly, the merchant and artisan class just described (again of any age), in order to preserve their own social position and self-respect, tend to adopt a more regulated and even rigid code of social behavior, directly suspicious of any “religious subtlety.” This frequently leads to their opting for much more literalistic approaches to religion as well as all of life’s many other concerns. It is for this reason, it is suggested, that the lack of a historically specific Christ figure (to match the figure of Osiris) would have become to these Alexandrians a source of great concern, whereas it had not for either the intellectuals or the Essene mystics. Hence some have considered it quite probable that the “Christian” monks practicing the Serapean Mysteries progressively allowed the figure of the Serapean sun god to be translated into a deified human Jesus figure. This was in acquiescence with the prevailing policy of those Church Fathers trying to make their belief system more potently and more widely attractive than that of the neo-Platonic and neo-Pythagorean gnostics.

CROSS-CORRESPONDENCES

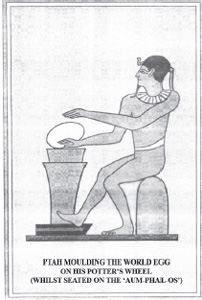

The Essenes of Qumran were otherwise later recognized as gnostics by the Church of Rome and were also known to have some form of connection with the Mysteries of Adonis—hence perhaps Christ being referred to in the New Testament as Adonai. Although not sun worshippers per se, they are otherwise known to have paid particular observance to the Sun, as mentioned earlier, and it is noteworthy that in those ancient times, the idea of a suffering celestial Messiah—symbolized by the Sun—was widespread. Being highly aware of the “Divine Builder” or “Divine Artificer” tradition, like that of Ptah in Egypt (see fig. 13.3), they would almost certainly have known of the parallel Hindu tradition in which the god Visvakarman (also the “Great Architect”) crucified his son Surya (the Sun) upon his swastika-like lathe, otherwise recognized as the Jain cross.

The origin of the Virgin Mother concept is also to be found among the Nazarenes in the statement concerning the Higher Mysteries, which, in the Greek tradition, were governed by the goddess Demeter: “For this is the Virgin who carries in her womb and conceives and brings forth a son, not animal, not corporeal but blessed for evermore.”21 It is therefore not difficult to see how the mental association of Mary (a name perhaps derived from the adorational Egyptian name Meri-Isis—meri meaning “beloved”)—the mother of Jesus—could perhaps have been derived by ignorant mis-association with the Spiritual Soul principle represented by Demeter. In the Egyptian tradition, Isis metamorphosed into the hierarchically higher figure of Hathor (Hat-Hor), the All-Mother goddess who was herself united theologically with Atum-Ra, the “grandfather” of Osiris and generator of the objective world. So it would not have been unduly problematic for the early Christian bishops, in their selective theological borrowings, to justify to themselves the concept of Meri-Isis-Hathor—subsequently shortened to “Meri” (or Mary)—being (mis)represented as “Mother of God.”

Fig. 13.3. Ptah at the potter’s wheel

CONCERNING THE CHRIST AVATAR

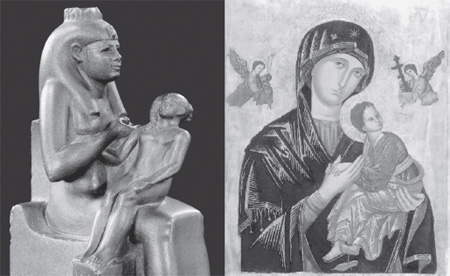

Reverting to the subject of the literal-minded merchant and artisan class of Alexandria, we turn next to the issue of the Avatar or Messianic Savior figure. This is the officially executed and risen Christ at the center of Christian theology, seemingly derived from the Serapean philosophy. This laid particular attention on the figure of Isis and the Horus child she bore as the reincarnate Osiris (see fig. 13.4)—hence “the only begotten son of the Father.” What now followed from all this, it is suggested, is manifold and complex.

Fig. 13.4. Isis and Horus compared to Mary and Jesus

First of all, it is widely acknowledged that in all ancient traditions the end of the astrological era was marked by surges of Messianic utopianism or apocalypticism. That is because the end of the zodiacal Age always supposedly heralded the wondrous birth appearance of an Avatar, or spiritual Savior. This then became—in the Western sense—a “son of God,” to be known by the Greek name Kristos, “the Anointed One.” The implication therefore (to the literal minded at least), was that, by the beginning of the first century CE—the millennium by then having passed—such an Avatar must already quite logically have been born, although to begin with it was not objectively apparent who he was or might have been. Secondly, it is clear that the majority of the early Church Fathers (who had borrowed their main core of theological concepts from the earlier gnostic traditions of Alexandria) failed to understand that the Trinity responsible for Creation of the world and humanity was in fact merely the expression of the Demiurge.

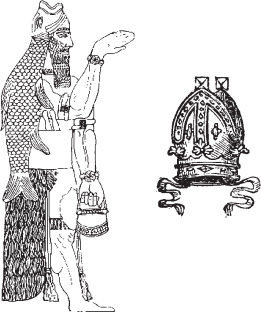

As described in earlier chapters, it was commonly understood in the ancient philosophical world that the One Divinity behind all existence was not a Creator but a kosmic Consciousness; that its primary point of emanation (the kabbalistic Keter) produced a secondary emanation (Mind, or Nous—the much later kabbalistic Hokmah); that this then gave rise to the tertiary principle (the Demiurge), a hierarchical group of advanced Intelligences, which was itself the true Creator. The latter then expressed the Will-to-be, the Will-to-know, and the Will-to-create/adapt, parallel to the repetitive Siva-Visnu-Brahma Trimurti of Hinduism and the corresponding Anu-Ea-Bel of Babylonian religion—hence the derivation of the Christian Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. However, in the Hindu tradition—even then well known throughout the Middle East—the primary field of kosmic or Universal Consciousness was represented by Visnu (directly associated with the fish symbol), whose emanation gave rise to the decidedly avataric boy-god Krisna. One might also mention here the avataric Babylonian fish-god Oannes as another source of inspiration. One can see from fig. 13.5 of Oannes where the idea of the miter (the ceremonial hat worn by the Christian bishop or archbishop) actually arose—that is, symbolizing the gaping mouth of the fish, itself representing the crown chakra—thereby again confirming Babylonian influences on the formulation of early Christianity.

Fig. 13.5. The Babylonian ocean god Oannes (left) and the bishop’s miter

Bearing these facts in mind, it is therefore suggested that some of our esoterically incompetent early Christian theologians must evidently (and quite wrongly) have taken this emanation of the Visnu principle to represent the literally emanated “Son” of the Father-God then cyclically due. In the corresponding Babylonian tradition, from which the Hebrews had returned in the fifth century BCE, their Dagon and Oannes were also “man-fishes” and presented as Messiahs. That the same historic period involved the beginning of the zodiacal Age of Pisces will almost certainly have reinforced their (erroneous) perception that the coming Avatar (of Visnu) had to be the actually historical “Son of God.” The phonetic similarity of the names Kris-na and Kris-tos undoubtedly helped.

One predisposing factor specifically points to when the figure of the Jewish Jesus was actually incorporated into the early Christian theology. It is that of Roman overlordship of Judea and Palestine, which only began during the early first century BCE. The fact that the Jewish king (Herod) is reported as reacting to the idea of a great spiritual Avatar appearing with the astrological change of zodiacal era by ordering the first-born male children of the time to be killed—thereby forcing Jesus’ parents to flee with him to Egypt—is (if true) also indicative of a timeline. Taking into account calendrical changes, no modern astrologer is certain as to when the actual changeover from Aries to Pisces took place. However, as Chaldean astrology was held in such high regard, it is very likely that the three Magi (although themselves probably Zoroastrian) were following the true astrological timeline.

So we can see that Christianity was actually of a Greco-Egyptian gnostic origin. However, its roughly six-hundred-year period of initial existence as such—commencing in the Serapean temple tradition—came to an end in the fourth century CE. Then it was officially recognized as the religion of the Roman Empire, with Rome having already taken over control of Egypt as a colony around the turn of the millennium. But, with the general spread of early Christianity around the Mediterranean during the first two or three centuries BCE under Greek rule and then the next three centuries under Roman rule, it is not surprising that variations arose in their various belief and ritual systems. One of these would almost certainly have been focused on the issue of human divinity. At this earlier stage, although there were localized Christian “bishops” scattered around the Mediterranean countries, looking after even more scattered Christian groups, no one such group or single individual spoke for or otherwise represented the whole. All of them supported their own slightly differing belief systems.

Thus it was that in 325 CE the Council of Nicaea was called, specifically in order to decide theologically upon the relationship between God and Jesus, the latter being regarded as the “Christed” Son of God, the second “person” of the Holy Trinity. Its decision—that they were united in a single divinity—was ratified at the later Council of Constantinople in 381 CE after much bitter theological and political argument in between. At the latter Council, the enclave of bishops otherwise agreed that the Holy Spirit was to be regarded as the third “person” of the Holy Trinity. Thereafter, it was also decided—again after much argument—that Mary, the supposed mother of Jesus, was to be officially regarded as “Mother of God.” As we suggested earlier, however, this was purely derived from a combination of the Egyptian name Meri and the gnostic sacred metaphor of Sophia, the dark Isis-like figure yet to become another of the theological adaptations of early Christianity.

BUT WHO WAS JESUS?

Turing to the figure of Jesus (Jeshu[a] in the Hebrew), there appear to be several alternative possibilities in addition to the mentions by Josephus. Ea-Shu (these being the Babylonian and Egyptian gods of Light) is another, perhaps with a slight phonetic modification to the more Hebrew looking Jah-Shu and then to Jeshu(a)? It seems otherwise quite possible, from the little evidence available, that he could in fact have been a particularly successful and properly initiated gnostic teacher of the second or first century BCE, with his own following of disciples. The fact that they otherwise naturally held him to be their guru-savior and that their successors constantly referred to his sayings would probably also have become quite widely known. That one such guru figure might also have been identified by the Jewish Sanhedrin as a social troublemaker and subsequently crucified by the Romans at their behest is also not impossible. However, as the historical Pontius Pilate was well known as an overly violent ruler (warned against it by Rome), it is possible that his name was used later to engrave the memory indelibly in pliable local minds. His ready violence also fails to coincide with the way the New Testament describes him.

There are two such Jesus or Jeshua figures known to historians. The first was Jeshua-ben-Pantera. He was, so we are told, the son of a Roman soldier called Joseph-ben-Pantera who had seduced a local virgin named Miriam despite her betrothal to another man. Adopted by his uncle and having studied theurgical philosophy and practice in Egypt, this boy child (Jeshua) was recognized by the priesthood there as possessing unusual powers; he was then initiated by them and raised to high degree. Jeshua became known as a great healer and, returning to Judea, began a widespread evangelical movement, with his own retinue of disciples. He was later publicly censured by the rabbis for his teachings,22 then later condemned to death and hung on a tree around 100 BCE. The other figure of Jeshua-ben-Nun (whether earlier or later in time) is known for no such specific history but (because of Nun meaning “fish”) is in some ways a perhaps more likely candidate, due to the specific association with the incoming Age of Pisces. In support of that, the Tibetan Adept DK firmly states that Jesus and Jeshua-ben-Nun were one and the same.23

In practical terms, however, neither can positively be deduced by us today as the historical “Jesus of Nazareth” of the New Testament. Nor can we confirm that the two were not somehow combined into one persona by detail-careless local tradition over several generations. Notwithstanding this, as Blavatsky tells us: “Every tradition shows that Jesus was educated in Egypt and passed his infancy and youth with the Brotherhoods of the Essenes and other mystic communities.”24 In addition, by virtue of the fact that he disagreed with his teachers on several issues of formal observance, he cannot strictly be regarded as an Essene himself.25 In fact, it is known that members of his family were Ebionites,26 a name which (by association with the Serapean religion) may well have been derived phonetically from the Egyptian Hpi—representing the supremely powerful but invisible divine force in Nature that gave the river Nile its powerful and annually regenerative current—plus the Greek suffix on. Thus a Hpi-on became an Ebion(ite).

The first Christians after the death of Jesus believed him to be a holy and inspired prophet and also a vehicle used by the Christos and Sophia (two complementary aspects of the Alexandrian gnostic philosophy) for their expression.27 With that as a background picture, and also taking into consideration what we have already otherwise mentioned, it is perhaps easy to see how later and more literal-minded supporters might have come to see him as an actual Christ figure. To some of those looking for the Avatar of the Age of Pisces this, it is suggested, thus meant that he logically had to be the Son, who was thereby also intended to be co-equal with God. This was apparently (according to early Christian theologians) based on the statement in the New Testament that Jesus (or rather the Christ, while overshadowing him) had made to the effect that “I and my God are One.” However, this ignores the (to us) self-evident alternative of the lesser consciousness of the microcosm evolving through progressive initiatory crises to become at-one with the greater consciousness of the Demiurgic Macrocosm, which had itself passed through the human stage eons before. To the esotericist, initiates of the third degree (and higher) are in a definite sense entitled to make this statement of conscious inner union because of realizing it to be a fact in a logical evolutionary progression. In addition, it is otherwise known, as Blavatsky tells us: “in the secret kabbalistic documents of the Nabathaeans . . . after the initiation, ABA the Father becomes the Son and the Son succeeds the father and becomes Father and Son at the same time, inspired by Sophia Ackamoth.28

It is otherwise apparent that all the scattered groups of proto-Christians in the Levant and extending through modern Syria and Turkey were originally of a gnostic persuasion, each going its own way in terms of philosophical detail. The original groups—in Palestine and Syria at least—appear to have been of either Essene or Druze (or similar) persuasion and, as already described, it has long been thought that the biblical figure of Jesus came from the former of these two secretive groups. However, irrespective of whether that is so, it is also fairly clear that “someone” went public and started teaching and proselytizing an esoteric Buddhist form of gnosticism—that a true self-knowledge and understanding of suffering leads to liberation from both29—on a rather more extensive basis, at some time between the written works of Philo and Josephus. That “someone” seems to have taken the form of an individual known as Jesus (or rather, “Jeshua”), who, for his enlarged vision, was proscribed by the Jewish Sanhedrin at Jerusalem, which then politically engineered his execution at the perhaps unwilling hands of the local Roman governor. That much of the story would appear quite logical and consistent with other references.

It is well known, however, among scholars of the subject, that several of the early Christian bishops—Eusebius, Ireneus, Clement of Alexandria, and St. Jerome among them—mercilessly altered by editorial forgery the older texts of Josephus and others for political reasons, to provide a better-sounding theological foundation for early Christians in the second and third centuries CE. On this same subject of retrospective amendment, the author Edmond Bordeaux Szekely has a great deal to say in his work, The Essene Origins of Christianity. However, he lacks any basic esoteric perception, failing to understand the conceptual nature of the Word or the Holy Spirit, or to appreciate the factor of “overshadowing” of a disciple by a Master initiate. He thus considers the whole issue of the real Jesus from a purely materialistic viewpoint, although he does in passing mention a variety of highly important historical facts concerning the supposed background of the biblical Jesus.

One of these is that the town of Nazareth did not even exist until at least the eighth century CE, nor was there such a place-name until then. It appears that the Christian Church fathers of the time realized this fact and immediately had one selected and constructed so that “Jesus of Nazareth” was associated with a known location reasonably close to Bethlehem (where by prior Judaic tradition the Messiah was supposed to be born), rather than confirmed as being born among the Essene “Nazarenes” or “Nazirites.”30 A second is that the very word nazar (itself as n-z-r) meant “consecrated to Yahweh” and was applied to all the first-born sons of Jewish families under Mosaic law.31 It is curious to learn that the term actually derives from the Sanskrit root nag, meaning “a serpent,” but esoterically denoting an initiate, a nagar. Even more curiously, we learn that the same word, borrowed by the Arabic (as nas’r), means “one who is of the offspring of Muhammad”—hence also an initiate by inference rather than being of Muhammad’s family bloodline. This latter fact is overlooked by modern historians and Islamic theologians alike.

It would then seem that, in the aftermath of his crucifixion—whether he survived it or not—this Buddhistic gnosticism survived and flourished (under the aggressive guidance of St. Paul), becoming “Christianized” because its followers saw Jeshua as a spiritual teacher—a “Krisna”—who had laid down his life for them. That they took this view would quite naturally have become well known and, as this was a rare example of a spiritual individual following a particular Path, it would not have been surprising to find elements of his personal life story becoming magnified in importance over succeeding decades and centuries to become the stuff of at least local legend. For example, the story of Krisna has him descending into the Underworld, just as Jesus is supposed to have done following his death. The wholesale adaptation of this story to Christ-hood by less knowledgeable and more politically orientated quasi-gnostics would thus prove very simple.

THE GNOSTIC ALTERNATIVE

Let us now look at the perhaps less obvious alternative. As David Fideler interestingly explains for us in his work Jesus Christ, Sun of God, the Greek version of the name Jesus amounts in terms of gematria to the number 888, which was mystically as well as mathematically related to the Spiritual Sun.32 As the Greek alphabet was itself based on the octave, the further implication was that the name Jesus represented the alpha and omega and that it accordingly possessed an occult potency above all other possible names.33 From a slightly different viewpoint, however, the number 8 (as ∞) mathematically represents an infinity, while in esoteric terms it is also the octave containing the septenary system. This, as we saw in earlier chapters, is also symbolic of the soul principle. The latter is similarly represented, whether in the human individual or as the Oversoul of a celestial body.

Following on from that in kabbalistic terms (Yah being the same as the Chaldeo-Babylonian god Ea), the soul principle is the same as the third sephiroth Binah, a name derived from the compound ben-Yah, meaning the “son of God.” Hence the further implication arising in the minds of early gnostic Christians is that the 888 actually represented the united Trinity, which was emanated by the Deity—that is, as Divine Soul, Spiritual Soul, and terrestrial or human soul. In other words, the name Jesus was itself suggestive of God incarnate, as the avataric Christos.

From the rather more systematically hard-headed viewpoint of a real esotericist, however, this is nonsensical when applied to an individual and purely the result of wishful thinking. Nevertheless, in an intellectual and mystical “hothouse” atmosphere like that of Alexandria at the time of naturally great expectancy accompanying the change of zodiacal Age from Aries to Pisces, it would not have been altogether surprising to find such extreme “New Age” views being dramatically introduced to support a particular viewpoint to a mystically impressionable audience. As David Fideler further adds:

As Christianity evolved into a collective belief system, it developed a political structure and creeds, teaching that Jesus came and left at a particular point in time . . . it outlawed other forms of religious expression. . . . The Church thereby proclaimed itself as the official mediator between man and God, thus usurping the original function of Christ the Logos.34

We otherwise know for a fact—because of the “gnostic gospels” in the Nag Hammadi texts—that the figures of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and at least some of the disciples were well known in literary terms to the local gnostic community of the time. But whereas these documents have been taken by at least some of the modern Christian community as confirming the existence of the historical Jesus, others naturally reject the idea because the gnostic philosophy, which he is shown as teaching, was extensively allegorical in nature. This appears superficially unhelpful. But what if this particular gnostic literature and its teachings were historically rather older than our academics imagine? As already suggested, we know that various forms of gnostic philosophy were already being discussed and considered in Alexandria much earlier, by at least two centuries, as a result of the city having become a psycho-spiritual “melting pot” for all sorts of mystical, occult, and philosophical ideas drawn from around the Near East and Middle East, seemingly extending as far as India and China.

So what if the early Christians were indeed a breakaway (originally gnostic) group of misguided “fundamentalists” who had come to believe that the entirely mythical figure of Jesus in their Gospels “must” in fact have been a historical being? Would that perhaps not help to explain why so many of the “attached” characteristics of Jesus—which clearly (as acknowledged by historians) derive from Mithraic, Hindu, and other mythic philosophy—became part of the description surrounding him? Some of those “attachments” have already been mentioned earlier in this book. They include: the fact that the Hindu god Visvakarman was represented as a carpenter—hence Jesus being the “son of a carpenter”; the fact that the crucifixion and use of a crown of thorns were taken from the story of the god Indra; the fact that the “virgin birth” and the associated idea of his being the “Son of God” were associations common with all mythic gods in the ancient world, for example in the case of the Greek Dionysus.

The further associated idea of the Divine Trinity is itself a basically universal gnostic concept, while Mary, the supposed mother of Jesus, is already acknowledged by many scholars as a purely literal and anthropocentric parallel to the gnostic Sophia. However, the latter idea involves a very basic compound misconception because the gnostic Sophia represented the “wisdom-breath” of the Logos, which is a far cry from “the mother of God” in a strictly personalized sense.

It is perhaps worthwhile drawing a further parallel here, that between the kabbalistic Keter—the primordial emanation of Ain Soph—and the Greek term Logos. The latter, as David Fideler reminds us, conveys the meanings of order and pattern, or ratio, plus causation and mediation.35 It is thus associated with Man, the “fallen” spirit who, as we saw in earlier chapters, represents the Higher Purpose that is to be imposed upon the kosmic Underworld. In the Greek system of Platonic philosophy, the term Logos signifies not only Divine Order but also, quite logically, the “son of God” emanated from the Unknowable GOOD (i.e., from Ain Soph in equivalent terms). This emanation thereby gave rise to the creative “Architect” or “Second God,” which, in turn, gave rise to the originally Platonic concept of the Demiurge, which the later Christian gnostics so horrendously distorted. The Logos is otherwise directly related to the Nous or Universal Mind from which all possible forms are derived. It is also the Source of all existence, thereby being the origin of both life and light in the lower world system. Now, in the true gnostic tradition, the fully Self-realized man is a perfected expression of the Divine Mind. He, the initiate of the seventh degree (the Manushi Buddha), is the Christ who, as the “Son of the Father” acts as the avataric “Redeemer.” However, instead of properly relating this to humanity as a whole, early political Christianity chose merely to idealize it by singular association with the supposedly historical Jesus and their own formative religion.

If the New Testament Jesus did not in fact exist and if the foregoing is indicative of the more accurate derivation of the story surrounding him, it clearly throws some large question marks over the actual theology of the Christian religion, just as literal (and unsupported) belief in the supposed historicity of the Hebrew patriarchs undermines the basis of the Judaic religion. However, as at least one modern British archbishop has openly declared that, even if Jesus did not exist, he would still remain a fully committed Christian, perhaps it is the gentle core of Christian philosophy (so akin to Jain and Buddhist philosophy) that is in any case the more important to our modern humanity in general. But then what of the alternative “Jesus” figure who seemingly became an Adept? It seems, from other information that has come my way, that something of the truth is known to at least some of the Sufi sheiks in the Middle East. However, at present, the Adept Brotherhood itself evidently sees fit to let the “waters” of public opinion and orthodoxy remain undisturbed by any further revelation.

Further puzzlement at the Adept Brotherhood’s real attitude is otherwise provided by the many positive references to the sayings and nature of both Jesus and the Christ respectively in The Secret Doctrine. By way of example, we find such forthrightly emergent statements as: “For the teachings of Christ were occult teachings. . . . They were never intended for the masses”36 and “Christos is the seventh principle, if anything.” Blavatsky was also to add that “Neither Buddha nor ‘Christ’ ever wrote anything themselves, but both spoke in allegories.”37 From these it is clear that the Adept Brotherhood is not actually rejecting the reality of their existence at all, as so many “back-to-Blavatsky” enthusiasts make out through careless reading and assumption. The fact that Blavatsky refers to “Christ” in parenthesis even implies that the real Adept behind that title was in some degree comparable to or associated with the Buddha. We shall look at this idea in further detail a little later on, in the next chapter.

OTHER ADEPT TEACHERS OF THE TIME

Some further interesting parallels are to be found in the life of Apollonius of Tyana (see fig. 13.6), a neo-Pythagorean (hence also gnostic) ascetic and theurgist who was apparently a near contemporary of the real Jesus of Nazareth.38 He was born in Cappadocia, seemingly during the early-to-mid first century CE, according to historians. The Adept DK openly states that Apollonius was the next (although not necessarily immediate) reincarnation of the historical Jesus, becoming a full Master in that incarnation,39 after travelling to India to meet the Adept Hierarchy of the time.

Fig. 13.6. Apollonius of Tyana

We know something of his extraordinary story from the historian, his friend and travelling companion, Philostratus. From the latter we understand that Apollonius’s birth was attended by “miracles and portents” and that at the age of sixteen he set out to adopt the type of monastic life ascribed to Pythagoras, renouncing wine, women, and the eating of flesh. As well as these he allowed his hair to grow long just like the Nazarenes, also wearing only a linen garment and never wearing shoes. He developed a widespread reputation as a deeply holy man, a social reformer, exorcist, and well-known healer. He was also known to have travelled to India, Persia, and Egypt, learning of the deep occult skills and philosophies of their Adepts, which he was himself thereafter able to demonstrate. Two of these involved the ability (at will) to suddenly disappear or reappear and otherwise to appear in two quite different and distant places at the same time (by psychic projection).40

It is otherwise interesting to note that Apollonius actually, in one sense, prepared the way for the wider development of Christianity although, rather curiously, Christian historians of the third century CE went out of their way to denigrate him, suggesting among other things that Apollonius had far fewer and less dramatic powers than had Jesus.41 However, if nothing else, the story of Apollonius confirms that in the first century CE there were in objective or public existence very occasional individuals of Adept status so highly familiar with the theory and practice of occult philosophy that they left the deepest memory of their existence in the social traditions of the time. Temples and shrines to Apollonius were set up in different parts of Asia Minor as a rival to the Christian Jesus, and he is even reported by reliable authority to have attended before the Roman Emperors Vespasian and Titus.42 It is also interesting to note that Apollonius himself, who could remember his previous lifetimes, neither claimed to be a reincarnation of Jesus nor even mentioned him. However, one could say with some degree of logic that, had he known of his supposedly previous incarnation as Jesus, it was probably the last thing that he would have wanted to make public anyway.

MESSIANIC DISCIPLESHIP

We are otherwise told not only that the Christ and the Islamic Imam Mahdi are one and the same, but also that the Islamic religion involves part of the continuing work of the Master Jesus (now himself apparently a Chohan). We are also told that the prophet Muhammad was supposedly one of his chelas or disciples,43 albeit evidently unaware of the fact. Hence, it would appear that, by virtue of Jesus having apparently been a chela of the Christ, the Islamic religion—although founded on the (supposedly Hebrew) Old Testament—is or will become much more directly connected with Christianity than it currently is or appears to be. Bearing in mind the current problems in Palestine and Jerusalem between Islam and various mutually antagonistic forms of Christianity (quite apart from the input of Jewish Zionism), the development of this complex relationship should make for interesting observation during the next century or so. This is more especially the case as there is now a nascent school of academic thought querying whether much written about the character and personal history of Muhammad was itself merely a manufactured myth.44 The parallel with the academic argument over the last century as to whether Jesus really existed is obvious.

Bearing in mind that the Jewish religion is itself a cultural leftover from the Age of Aries, it is clear that its incompatibility with the Age of Aquarius will need to be cleared up. So when the further comment by the Tibetan Adept DK—that the Chohan Jesus will probably adopt the role of the Hebrew “Messiah”45—is taken into account with that in mind, it perhaps gives some indication as to the Adept Hierarchy intending that these three religious belief systems should hopefully reach some sort of mutual rapprochement in the relative nearness of time. For that possibility to emerge, however, the influence of theological extremists in each of the three religious camps will perhaps have to be progressively sidelined by wider public opinion.

In concluding this section on the question of whether a human individual known as Jesus or Jeshua ever actually existed in fulfillment of the biblical story, however, it becomes fairly clear that there is still (at least at present) insufficient evidence to confirm matters conclusively one way or another. This is irrespective of the fact that the Adept Hierarchy—through Blavatsky’s agency—have clearly confirmed that he was a gnostic Adept reformer and healer with a following of disciples, even if they have not confirmed exactly when he lived and died. For those concerned with history or theology this will undoubtedly continue to be frustratingly unsatisfactory. However, for the true esotericist who understands from experience something of the nature of how the Spiritual Ego overshadows the objective individual, it is of considerably less real importance. Nevertheless, let us now in the next chapter take a look at the further background to the corresponding mystery between the Christ, the Bodhisattva, and the Intelligence known to us as Maitreya Buddha.