The Seeds of Citizenship

GAD HEUMAN

Unfree labor did not come to an end in the anglophone Caribbean in 1834. Although the enslaved were declared legally free on August 1, they were obliged to serve a period of apprenticeship to their former masters. This meant that ex-slaves were legally obligated to work without compensation for their former masters for up to forty-five hours per week. Their term of continued compulsory labor depended on their status: former field slaves (praedials) were to be apprenticed for six years, while skilled apprentices and domestics (non-praedials) were to be fully free after four years. Because of the terms of the apprenticeship system, many contemporary observers as well as some historians have regarded it as a new form of slavery.1

However, Thomas Holt has called the apprenticeship “a half-way covenant,” since the relationship between the planter and the worker was much the same as slavery during part of the week, although the remaining time was negotiable.2 After serving their former masters for the requisite number of hours each week, ex-slaves were free to negotiate conditions of work and wages with their former masters or with another employer. Moreover, the legislation establishing apprenticeship prohibited former masters from punishing their former slaves. Instead, special magistrates were appointed, largely from England, to adjudicate disputes between erstwhile masters and slaves. Lord Sligo, the governor of Jamaica, recognized the crucial role of these magistrates in an August 1834 proclamation to the apprentices of Jamaica: “Neither your master, your overseer, your book-keeper, your driver, nor any other person can strike you, or put you into the stocks, nor can you be punished at all, except by the order of a Special Magistrate.”3

But apprentices across the Caribbean resisted the establishment of the apprenticeship system. Moreover, even before apprenticeship ended in 1838, many former slaves were unwilling to accept freedom on such terms. In addition, some apprentices never accepted the different lengths of apprenticeship for field and skilled laborers envisioned in the legislation. Apprentices not only imagined freedom very differently from their former masters but also began to see themselves as citizens.

Even before the onset of apprenticeship, there were early signs of trouble. In St. Kitts, the enslaved indicated that they would resist apprenticeship and would strike on August 1, 1834. As they explained to the island’s lieutenant governor, J. Lyons Nixon, they would “only work for wages, and that they will dictate terms, being convinced from the King’s Proclamation that they are to have unrestricted freedom on the 1st August next.”4

Faced with this outburst, Nixon toured the island, speaking to blacks from every estate. The lieutenant governor sought to clarify the basic provisions of the system and emphasized that the enslaved would need to continue to work after the abolition of slavery. However, his addresses failed to calm blacks, who remained hostile and in at least one instance threatened an overseer with violence. According to Nixon, the people in two parishes near the capital were “highly insubordinate and disgraceful. They una voce protested against the apprenticeship system, declaring their resolution to resist it, and not to work after the 1st of August without wages, saying that on that day they were to be free, as announced by the King’s proclamation, and that their masters could not take their houses or provision-grounds from them, having so long occupied them.”5

Serious difficulties arose at the onset of apprenticeship elsewhere in the Caribbean as well. In Trinidad, the apprentices vowed to strike and reiterated some of the same themes as the apprentices in St. Kitts. The hostility toward apprenticeship was equally strong in British Guiana. Apprentices in the province of Essequibo occupied a church and a churchyard for three days beginning on August 9, flew flags, and generally sought to encourage local residents to resist apprenticeship.6

In the Jamaican parish of St. Ann, apprentices went on strike, vowing not to work except for wages. One report claimed that the apprentices swore that “they will have their heads cut off, or shot, before they will be bound as apprentices.” As in other parts of the Caribbean, apprentices questioned whether the king could be responsible for the legislation or whether it instead emanated from Jamaica. They asked the authorities a series of rather telling questions: “1st. Is it the King’s law? 2d. Would you swear that the King make it? 3d. Did not the Jamaica House make it? 4. Did not Lord Sligo put him name to it because him have slaves? 5. Could you swear it is the Law of Jesus Christ?”7

Another level of protest was more generalized and more difficult to control. James Scott has described this behavior of peasants in terms of “hidden transcripts,” using “foot-dragging” or “poaching” as part of an everyday form of resistance. Apprentices in Jamaica employed such tactics. Governor Sligo commented on the reaction of many apprentices who were unhappy with the new system: they resorted to “turning out late, irregularity to work, and idling of time.” To some degree, these “delinquencies” were dealt with by the special magistrates, but planters also perceived “insolence and insubordination” among the former slaves. The use of language was significant in this context: a special magistrate, E. D. Baynes, reported that the apprentice was “daily becoming more heedless of and more disrespectful to his manager.” According to Baynes, apprentices were no longer willing to accept the language of their former owners without an appropriate retort.8

The reaction of the apprentices in the first year of the apprenticeship was highly revealing. Apprentices’ images of freedom clearly differed substantially from those of policymakers in the Colonial Office as well as former masters. For the apprentices, and especially those who resisted the establishment of apprenticeship, it was difficult to comprehend the new system. They felt that they needed no “apprenticeship”—no training for freedom or for their plantation work. In fact, the nature of the slaves’ economy in the Caribbean, with its extensive provision-ground system and highly developed markets, meant that the enslaved were probably better prepared for freedom than were their former masters.9 At the onset of apprenticeship, ex-slaves wanted to be fully free: they sought “unrestricted freedom” and not a system of forced labor, even for part of the week.

Yet the apprenticeship system placed considerable obstacles in the path of the former slaves. For example, many planters sought to extract the maximum amount of labor possible in this period and to deny apprentices the indulgences and allowances that they had received during slavery. In theory, the Abolition Act allowed apprentices the same allowances they had received during slavery. But since many of these allowances were a matter of customary practice rather than legislative statute, considerable numbers of masters withheld these allowances. Field labor gangs were denied water carriers, and field cooks for the gangs were also removed. During slavery, mothers of six or more children were exempt from field labor, but in many places, planters discontinued this practice and sent these women to work in the field. Similarly, aged and infirm former slaves who had also been exempt from field labor had to work in the fields. One of the stipendiary magistrates commented at length and bitterly about these policies:

This feeling has doubtlessly originated in a splenetic and exasperated feeling on the part of the planters, who, compelled to emancipate his slaves, for what he maintained at the time . . . to be an insufficient consideration, showed too generally . . . a perverse disposition to harass and oppress the apprentices, withholding from him every assistance and indulgence, though customary in the days of slavery, which the strictest interpretation of the statue would bear out; rigidly exacting the whole law from him . . . dragging him before the special justice on occasions the most trivial . . . too often manifesting a discreditable anxiety for the severe infliction of the lash; [and] exclaiming intemperately against [and] affronting [them] by gross and offensive language.10

During the apprenticeship period, there were also serious difficulties over the way the planters scheduled the apprentices’ work time. In Jamaica, the Abolition Law stipulated that apprentices had to work 40.5 hours per week for their former masters, but the law did not state how that time should be organized. The planters in Jamaica almost immediately adopted an eight-hour workday, which meant that apprentices had little time to cultivate their provision grounds, since Saturday was their market day and they were not supposed to cultivate their grounds on Sundays. The apprentices wanted to work a nine-hour day from Monday to Thursday and a half day on Fridays to allow them to work their grounds on that day, but their masters would not allow this. Swithin Wilmot has suggested that this schedule not only inconvenienced the apprentices but also “prevented them from pursuing alternative occupations to working on the estates. The apprentices were to be kept dependent on the estates for their livelihood so that when full freedom came they would have been accustomed to look to the estates for earnings.”11

There was an additional problem about the way planters regulated the work time of their apprentices to their own advantage. A stipendiary magistrate in Jamaica, Edmund Lyon, described a system in which, during the shorter days of the year, the planters allowed a couple of hours a day for meal breaks. However, during the longer spring and summer days, planters kept the same time for breaks but had the apprentices start work earlier and finish later. The result could be a workweek for the apprentices of an additional ten hours. The apprentices complained to Lyon, but he noted the difficulty of proving this practice since very few apprentices had watches.12

It was clear that the role of the stipendiary magistrates was to adjudicate disputes between the apprentices and their former owners. But the magistrates were sometimes stymied by the reluctance of apprentices to complain to them. One of the stipendiary magistrates in western Jamaica, J. W. Grant, reported that planters withheld allowances for the apprentices if they complained to the magistrates. Grant reported the reaction of an overseer in the face of such a complaint: “a few women came to complain that the nurses were taken away from their children by the overseer, and that he made use of the most brutal and insulting language in addressing them; for this, and because some of the others happened to ask a few questions about their rights, notice has been given that unless all the [live]stock etc, which they were allowed to rear on the property are taken up within a certain time, they will be shot.”13

Some of the stipendiary magistrates themselves were responsible for the harsh punishments of apprentices. The surviving diary of a stipendiary magistrate in Jamaica, Frederick White, offers a glimpse of the severity of some of the punishments meted out by these magistrates and the occasional response of an apprentice. White was particularly upset by apprentices disobeying his orders and, as he put it, “[putting] me at defiance.” He found four men guilty of this behavior within a couple of weeks of the beginning of the apprenticeship system and ordered each to receive thirty-six lashes; in addition, two women received fourteen days hard labor in the workhouse. White believed that another apprentice, Thomas Catney, was also insolent and would not go to work, again in the middle of August 1834. White had Catney given thirty-six lashes and reported in his diary “that this man had the impudence to tell me that I was paid by the White Man & not by the King, for which I gave him the extra 12 lashes.”14

For White, these were not unusual responses. White reported on the case of some “badly disposed” apprentices on an estate who, he claimed, were the cause of all the apprentices being dissatisfied. Since the overseer had already explained the law to them, the hostile “reception I met with then called for me to make a very severe example”—thirty-six lashes for these men as well. In another case, White dealt even more severely with the headman of an estate who allegedly had encouraged other apprentices to strike and to perform less work than was required. White ordered him to receive forty-eight lashes.15

Yet in a rare case in which an apprentice complained about having been struck by an overseer, White let the manager off with a warning. The manager admitted hitting the apprentice in the head, but White dismissed the case because no stick had been used. White was clearly overzealous in his use of the whip and was eventually dismissed, although over a different issue. But the number of floggings of apprentices generally—especially in the early years of the system—suggests that he was far from unique.16

Apprentices responded to these abuses and the attempt to control their labor in a variety of ways. For example, in the immediate aftermath of the abolition of slavery, apprentices were very reluctant to work beyond the time required by the new legislation. Apprentices were required to work for their former masters for up to forty-five hours per week; thereafter, they were free to hire their labor or not to work at all. In some parts of the Caribbean, apprentices were determined to do much less work than they had as slaves. In British Guiana, for example, apprentices decided to do no more than half the work they had done under slavery; moreover, they knew this was “the King’s order.”17 In Jamaica, Governor Sligo reported that the apprentices believed that working for wages would “perpetuate their slavery.” Sligo worried that such views would result in a lack of labor to harvest the sugar crop.18

Sligo had expected difficulties along this line for the first month or two of the apprenticeship system but had assumed that apprentices would subsequently begin working for wages. Writing privately to the colonial secretary, Thomas Spring Rice, in October 1834, Sligo reported that apprentices were unwilling to work for wages and that he saw no likelihood of improvement in the situation since as the apprentices “begin by experience to acquire a better knowledge of the law they appear to become more resolute in their determination not to do one particle more of work than they are forced by the law.” For Sligo, apprenticeship had changed the situation dramatically: apprentices were aware that they no longer faced punishment from their former masters. Since there were not enough stipendiary magistrates on the island, apprentices were not being punished as they should have been. Even worse, the apprentices had adopted “a system of passive resistance” in many instances.19

The situation greatly alarmed planters. One estate in the parish of St. Ann had nearly two hundred apprentices, but no stipendiary magistrates visited the plantation during the first three months of the apprenticeship system. From a situation at the beginning of August when the apprentices had been “civil, well behaved and obedient,” things on the estate had changed dramatically. According to a planter with over thirty years’ experience in Jamaica, by the end of October, apprentices “turn out to work when they like, do what they choose, take what days they like, in fact, do as they think proper.”20 A doctor who had lived in Jamaica for nearly twenty years and who was also a proprietor of a coffee estate, James Maxwell, believed that the apprentices had a wider agenda. By working as little as possible during the time required by the law and then refusing to do any paid work outside of it, apprentices were intent on destroying the apprenticeship system. Maxwell maintained that the planters would be unable to deal with the apprentices’ lack of labor; if this pattern continued, the apprenticeship system would end prematurely. Apprentices would therefore be freed of their apprenticeships.21

Less than a year later, the situation had changed quite dramatically. Sligo noted in July 1835 that apprentices were working for wages on nearly three hundred estates in Jamaica, though they refused to do so on twenty-two others. Sligo explained that some apprentices continued to equate paid labor with the possibility of perpetuating their enslavement, while other apprentices were unwilling to work for their own masters but did so for neighboring estates. It was important for Sligo to report this information: he was countering the planters’ claims at a series of public meetings that apprentices had continued to refuse paid labor.22

A few months earlier, stipendiary magistrate W. Hewitt had painted a more mixed picture of Jamaican apprentices’ attitudes regarding hiring out their labor. In the parish of St. George, some apprentices were working for wages, while others worked in exchange for the allowances they had received under slavery. Hewitt reported that other apprentices simply refused to work outside of the period that the law required.23 Across the Caribbean, apprentices appear generally to have accepted working for wages. As two of the stipendiary magistrates in St. Vincent reported in the summer of 1837, apprentices there were eager to earn money, although some continued to work for their former allowances.24

Whatever their patterns of work, apprentices were prepared to initiate complaints about their masters to the stipendiary magistrates. In December 1834, Governor Sligo reported that apprentices had “lost all apprehensions now of the danger of making complaints, and avail themselves most abundantly of that privilege,” although Sligo found many of the charges “frivolous.”25 Moreover, the stipendiary magistrates clearly were punishing some planters. Sligo believed that fines—particularly those imposed on overseers—would limit oppression of their apprentices. Despite overseers’ denial of the charges against them, Sligo believed publishing such complaints would result in the overseers’ dismissal.26

While many stipendiary magistrates doled out harsh punishments, others did not. A few months after the start of the apprenticeship system, planters in Jamaica were complaining about the relatively light punishments meted out by the stipendiary magistrates. Moreover, planters’ representatives in the House of Assembly maintained that Sligo had instructed the special magistrates to decide all the cases against the planters. Some of the magistrates, among them William Norcott and Richard Hill in Montego Bay, were known opponents of corporal punishment. For Sligo, their refusal to hand out such punishments had led to the apprentices’ passive resistance to the demands of the planters. As Sligo put it, “The Negroes when brought before any other Special laugh at him and their Masters and say they will go to Hill & Norcott, who won’t allow them to be punished.”27 While this was a highly unusual stance, many apprentices were aware of the advantages of the apprenticeship system. As one of the stipendiary magistrates reported, the law was not what the apprentice had wanted or expected, but “it is at least a protective one to him, and that by good behaviour he has the power of securing himself from the aggression of the tyrannical or the persecution of the vindictive.”28 As the governor of Barbados, Sir Murray MacGregor, noted in 1837, apprenticeship had transferred the power of punishment from the former master to the stipendiary magistrate, a clear improvement, MacGregor believed, over slavery.29

There was another advantage for the apprentices: unlike the enslaved, apprentices had the right to buy themselves out of apprenticeship. The process could be difficult, since the method of appraising the value of the apprentice’s labor favored the former owners. Tribunals consisted of a stipendiary magistrate but also two colonial justices, local residents who might well have had an interest in apprenticed labor. An anonymous letter to the Colonial Office, apparently from an apprentice, also complained about this situation. Writing from Barbados soon after the beginning of the apprenticeship system in 1834, the apprentice criticized the oppressiveness of the system but specifically highlighted the exorbitant cost of appraisement. The apprentice concluded that “there has been many apprentices buying their time but the Price is too much . . . paying more than they would bring without emancipation.”30

Yet it is clear that some apprentices were able to purchase their manumission. In a return of the Jamaican valuations from November 1, 1836, to July 31, 1837, over one thousand apprentices were successful in gaining valuations for their remaining time and were therefore manumitted. These apprentices paid a total of nearly thirty thousand pounds to their owners for their manumission. However, during the same period, almost half as many apprentices, about four hundred of them, found the valuations too high and were not manumitted.31

The reports of the stipendiary magistrates generally indicate a strong desire on the part of the apprentices to manumit themselves. Some wished to do so to avoid continued ill treatment by their masters, borrowing money to purchase their freedom and agreeing to work to repay the debt. Others similarly sought to work for different masters or mistresses or to unite families. One report suggested that many of the manumitted apprentices were young girls and boys, whom the parents manumitted so that the children could be educated or trained in a trade.

Whatever the motivations, few of the manumitted apprentices continued in field labor. As one apprentice reportedly said, “Who ever hear of free work a field?”32 Many skilled apprentices continued at their trades, but many women left working as field laborers, preferring domestic work or trading as hucksters.

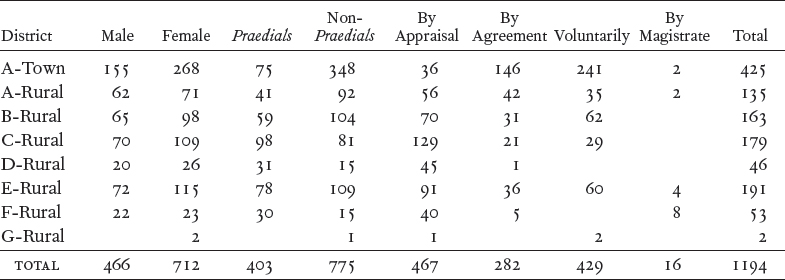

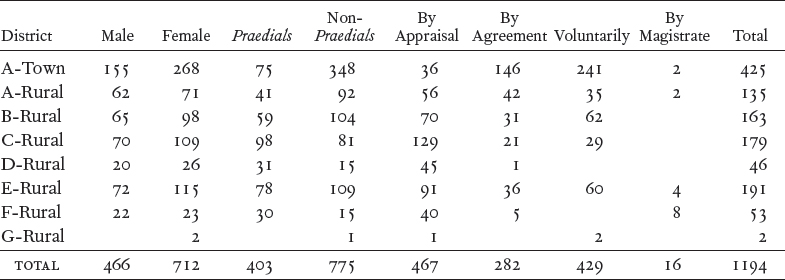

Table 1 shows that in Barbados, females were more likely than males to be manumitted and that non-praedials were more likely to gain their freedom than were praedials. Both findings are not surprising, especially in light of the preponderance of female domestic workers among the apprenticed population. Most of these apprentices went through the process of appraisal, the official route for manumission, but a significant proportion were discharged by mutual agreement of the master and the apprentice or voluntarily (without payment). The total number of manumitted apprentices for 1837, almost twelve hundred, was significant.

TABLE 1

Barbados, Number of Apprenticed Laborers Manumitted, 1837

SOURCE: “General Return of Appeals of Apprenticed Labourers from the Praedial to the Non-Praedial Class, Barbados, June 14, 1838,” Colonial Office Series 28/122, National Archives, Kew, London. Errors in the tabulation are in the original.

The data also suggest that the number of apprentices gaining their freedom increased rather than decreased as the end of apprenticeship neared, at least for the non-praedial population. In 1837, two stipendiary magistrates in St. Vincent reported that apprentices strongly desired to purchase their manumission.33 The following year, Barbados saw a rush to manumission despite the approaching end of the apprenticeship system. One of the stipendiary magistrates for Bridgetown, Henry Loving, reported in February that the non-praedials were “every day becoming more anxious for their Discharge, and that some who cannot obtain it by the usual means, exhibit such restiveness and bad conduct, as to oblige their Proprietors to dispense with the remaining term of Service rather than be tormented by such disaffected persons.” A month later, Loving reported that the “intense longing for unequivocal freedom is the only motive by which the slave of 1833 is guided at this moment.”34 In his district, the number of appraisals rose each month, and by the early spring of 1838, before the Barbados legislature ended apprenticeship, masters were voluntarily freeing their apprentices.

Before this rush of voluntary manumission, there was a very revealing report from St. Vincent in early 1838 that the non-praedials were anxious to be manumitted, even at that late date, because they wanted to purchase their own manumission and not be “indebted to the Law.” Such sentiments strengthened once the legislation ending apprenticeship had been enacted. One stipendiary magistrate in St. Vincent reported that apprentices did not want to be “‘a Queen Adelaide’s Man,’ that is free by the operation of the Law or as they say ‘that Buckra may change his mind again and make the Apprenticeship longer.’”35 In St. Vincent and probably elsewhere, apprentices had very clear ideas about freeing themselves. As in the period after emancipation in 1838 when there was a concern about reenslavement, there was also a fear at this point that the whites could lengthen the period of apprenticeship.

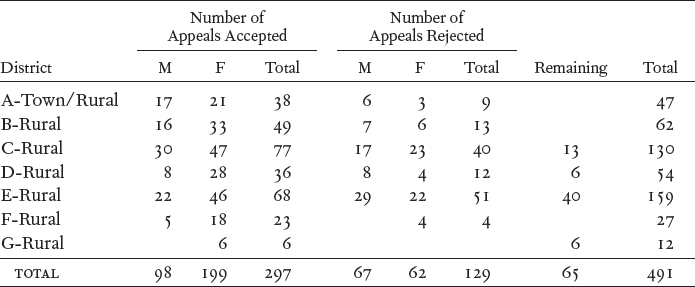

TABLE 2

Barbados—Categorization Appeals, December 1, 1837–March 1, 1838

SOURCE: “General Return of Appeals of Apprenticed Laborers Transferred from the Praedial to the Non-Praedial Class, December 1, 1837–March 1, 1838,” Colonial Office Series 28/123, Folio 40, Appeals, National Archives, Kew, London.

Masters and their apprentices also clashed over the classification system that determined whether an apprentice was a praedial (and therefore required to serve a six-year apprenticeship) or a non-praedial (a four-year apprenticeship). The legislation delineating the categories of apprenticeship was fairly complex, but what became clear almost immediately was the former owners’ intent to classify many apprentices as praedials and therefore to have their services for the projected six years of the apprenticeship period. One stipendiary magistrate in Jamaica noted that many masters had categorized their apprentices without informing the apprentices themselves. The absence of significant checks on the planters meant that many apprentices might “be defrauded of their freedom, and be illegally detained in bondage until 1840.”36

But as with the issue of compulsory manumission, many apprentices were aware of their rights and appealed against their categorization. The governor of Barbados reported in the spring of 1838 that there were a considerable number of apprentices in the process of challenging their categorization. The number of appeals on this issue reinforced the governor’s view. As table 2 shows, between December 1837 and March 1838 almost five hundred appeals of categorizations were filed in Barbados, and nearly three hundred of them succeeded. Going back to the summer of 1837, almost 570 of 877 appeals succeeded.

However, as with the abolition in 1834, apprentices knew that there was a campaign in Britain to bring apprenticeship to an end before its scheduled date. As agitation in Britain increased and some of the smaller islands of the eastern Caribbean began to legislate an early end to apprenticeship, some reports suggested that the system could not last. In the summer of 1838, a stipendiary magistrate in St. Vincent suggested that apprentices would undertake passive resistance if they had to continue as praedials after 1838.37

The abolitionist press in Britain—and particularly the British Emancipator—had far more ominous reports about potential trouble in 1838. It republished an article in a Jamaican newspaper threatening serious resistance; one black man reportedly said that “if all not free [in August 1838], the whole country will rise, and we will see what buckra and the mulatto can do with us, for we too much for them.” The Emancipator also suggested that the praedials had never accepted the distinction between themselves and non-praedials, and that as a result, on August 1, 1838, “the entire class of field labourers will claim to be placed on a footing with their fellows, and . . . they will enforce those claims by adopting a system of passive resistance—by quietly, but with dogged determination, laying down their hoes and refusing to work any longer as slaves.” Although the Emancipator discounted some of the language in these reports, it concluded that these views generally reflected the outlook of most of the apprentices.38

Apprenticeship ended completely on August 1, 1838, leaving formerly enslaved persons with the same legal rights as whites, including the right to vote, provided that they met the qualifications. Jamaica had imposed only minimal requirements for the franchise to allow all classes of whites to vote. The planters immediately sought to raise the requirements for the franchise after emancipation, fearing the consequences of an enfranchised black electorate. The Colonial Office in London repeatedly disallowed this legislation, however. Although the electorate was a tiny proportion of the population as a whole, blacks accounted for a sizable share of the voters.39

The Jamaican press highlighted concerns about the black electorate. Even the free colored press was worried about the power of the blacks: one such newspaper in the north of the island, the Falmouth Post, noted that the blacks had the power to return assemblymen who were “friends of the people” who would respond to the “unwashed constituency.” It was clear that the planters were not alone in worrying about the vote of the ex-slave population.40

In the period following emancipation, many blacks helped to elect black and brown members of the House of Assembly. Assemblymen responded to this electorate. For example, one successful brown candidate for the assembly told an election meeting in his parish that the “whites had had their own way long enough and it was time to put them down.” Another brown politician advertised himself as one of the “sons of Jamaica” and noted that natives should have a greater share in the running of the island. Similarly, the first black man in the House of Assembly in Jamaica, Edward Vickars, appealed to the black electorate with his slogan, “Vote for Vickars, the Black Man.” Building on their response to apprenticeship, blacks after emancipation clearly had a significant political role, and many of them opposed the politics of the planter class.41

Blacks built on the gains they had made during apprenticeship and at the onset of full freedom. Although different from slavery, apprenticeship had sought to severely restrict the apprentices. Many apprentices therefore resisted the apprenticeship system at its outset and also sought to obtain manumission or reclassification to be released early from apprenticeship.42 Because of the harshness of apprenticeship and the continued restrictions on free people at the moment of full freedom, many former slaves left the plantations and acquired land of their own. This meant that some of them could vote and could influence politics in ways that were very different from the politics of the planter class. This was also the case in Louisiana, where as Richard Follett has noted, “Former slaves wished to put freedom into practice by halting work, to attend political meetings, striking for higher wages, and walking off the job.”43 In the process of this politicization, former slaves began to see themselves as citizens.

1. The most comprehensive treatment of apprenticeship remains W. L. Burn, Emancipation and Apprenticeship in the British West Indies (London: Cape, 1937). See also William A. Green, British Slave Emancipation: The Sugar Colonies and the Great Experiment, 1830–1865 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1976); William A. Green, “The Apprenticeship in British Guiana, 1834–1838,” Caribbean Studies 9 (1969): 44–66; Thomas C. Holt, The Problem of Freedom: Race, Labor, and Politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832–1938 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); Douglas Hall, “The Apprenticeship Period in Jamaica, 1834–1838,” Caribbean Quarterly 3 (December 1953): 142–66; Swithin Wilmot, “Not ‘Full Free’: The Ex-Slaves and the Apprenticeship System in Jamaica, 1834–1838,” Jamaica Journal 17 (1984): 2–10; W. K. Marshall, “Apprenticeship and Labour Relations in Four Windward Islands,” in Abolition and Its Aftermath: The Historical Context, ed. David Richardson (London: Cass, 1985), 203–24; Demetrius L. Eudell, The Political Languages of Emancipation in the British Caribbean and the U.S. South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Diana Paton, No Bond but the Law: Punishment, Race, and Gender in Jamaican State Formation, 1780–1870 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004). See also Natasha Lightfoot, Troubling Freedom: Antigua and the Aftermath of British Emancipation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), which deals with a plantation colony in the anglophone Caribbean that rejected apprenticeship.

2. Holt, Problem of Freedom, 56–57.

3. Supplement to the Royal Gazette, August 16–23, 1834, Proclamation: Sligo to the Newly Made Apprentices of Jamaica.

4. British Parliamentary Papers (hereafter BPP), 1835 (278-2), vol. 50, Nixon to Stanley, July 10, 1834, no. 198. See also Robert S. Shelton, “A Modified Crime: The Apprenticeship System in St. Kitts,” Slavery and Abolition 16 (December 1995): 331–45.

5. BPP, MacGregor to Spring Rice, July 21, 1834, no. 200.

6. Supplement to the Royal Gazette, September 13–20, 1834; BPP, 1835 (278-I), 50, Smyth to Spring Rice, August 9, 1834, no. 113, Smyth to Spring Rice, October 12, 1834, no. 3.

7. Postscript to the Royal Gazette, August 2–9, 1834.

8. James Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), xiii; Sligo to Glenelg, March 5, 1836, no. 362, encl. Murchison to Nunes, March 1, 1835, Colonial Office Series 137/215, National Archives, Kew, London (hereafter co); BPP, 1836, (166-I), vol. 48, Sligo to Glenelg, April 2, 1836, encl. Report of E. D. Baynes, March 28, 1836, 343.

9. For an important collection on this theme, see Ira Berlin and Philip D. Morgan, eds., The Slaves’ Economy: Independent Production by Slaves in the Americas (London: Cass, 1991).

10. BPP, 1838 (154-I), Part V, Jamaica, Stipendiary Magistrate Report, E. D. Baynes, July 1, 1837, 305.

11. Wilmot, “Not ‘Full Free,’” 7

12. BPP, 1838 (154-I), Part V, Jamaica, Stipendiary Magistrate Report, Edmund B. Lyon, June 30, 1837, 300.

13. Ibid., Stipendiary Magistrate Report, J. W. Grant, July 12, 1837, 286.

14. Diary of Frederick White, Stipendiary Magistrate, in Jamaica, August 15, 1834, 27, Rhodes House, Oxford; ibid., August 18, 1834, 37.

15. Diary of Frederick White, August 18, 1834, 33, 36.

16. Ibid., 31.

17. BPP, 1835 (278-I), Part II, British Guiana, Smyth to Spring Rice, August 9, 1834, no. 114, 156.

18. Sligo to Spring Rice, October 12, 1834, Sligo Private Letterbook, Sligo Papers, MS 281, National Library of Jamaica.

19. Ibid.

20. BPP, 1835 (177), Part I, Jamaica, Examination of Mr. Towson, October 31, 1834, 51.

21. Ibid., Examination of Dr. James Maxwell, November 24, 1834, 100.

22. BPP, 1835 (278-I), Part II, Jamaica, 1833–35, Sligo to Glenelg, July 18, 1835, no. 143, 267.

23. Ibid., Sligo to Aberdeen, March 27, 1835, no. 38, encl. letter from W. Hewitt, Special Justice, March 24, 1835, 29.

24. Tyler to Macgregor, August 9, 1837, no. 71, Report of Pitman, Stipendiary Magistrate, July 3, 1837, Report of Polson, Stipendiary Magistrate, July 25, 1837, all in CO 260/55.

25. BPP, 1835 (177), Part I, Jamaica, 1833–35, Sligo to Spring Rice, December 9, 1834, no. 23, 63.

26. Sligo to Glenelg, February 8, 1836, Sligo Private Letterbook.

27. Sligo to Spring Rice, October 15, 1834, in ibid.

28. BPP, 1835 (278-I), Part II, Jamaica, 1833–35, Lyon to Sligo, July 1, 1835, 242.

29. MacGregor to Glenelg, June 12, 1837, no. 133, CO 28/119.

30. Anonymous to Spring Rice, October 1, 1834, CO 28/114.

31. BPP, 1838 (154-I), 1838, Part V, Jamaica, Abstract of the Return of Valuations, 89–90.

32. Ibid., Stipendiary Magistrate Report, W. A. Bell, July 2, 1837, 310.

33. Report of Polson, Stipendiary Magistrate, Second District, February 1838, Report of John Colthurst, Stipendiary Magistrate, Fifth District, March 31, 1838, both in CO 260/56.

34. MacGregor to Glenelg, March 20, 1838, no. 60, encl. Report of Henry Loving, Stipendiary Magistrate—Town District A—For February, CO 28/122.

35. Report of Polson, Stipendiary Magistrate, May 1838, Second District, CO 260/57.

36. Stipendiary Magistrate Report, E. D. Baynes, July 1, 1837, 306, in ibid.

37. Report of Polson, Stipendiary Magistrate, July 1838, Second District, CO 260/57, 301.

38. British Emancipator, April 11, 1838.

39. Gad J. Heuman, Between Black and White: Race, Politics, and the Free Coloreds in Jamaica, 1792–1865 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1981), 119.

40. Falmouth Post, January 19, 1849.

41. Elgin to Stanley, December 23, 1845, no. 105, CO 138/285; Falmouth Post, July 24, 1849; “The Elections—The Franchise,” Jamaica Monthly Magazine 1 (October 1844): 482–83.

42. For a useful discussion of apprentices (patrocinados) in Cuba also seeking freedom in the 1880s, see Rebecca J. Scott, “Defining the Boundaries of Freedom in the World of Cane: Cuba, Brazil, and Louisiana after Emancipation,” American Historical Review 99, no. 1 (February 1994): 82.

43. Richard Follett, Sven Beckert, Peter Coclanis, and Barbara Hahn, Plantation Kingdom: The American South and Its Global Commodities (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), 77.