Contrary to conventional wisdom that entertainment media portray science and scientists in a negative light, research shows that across time, genre, and medium there is no single prevailing image and that both positive and negative images of scientists and science can be found. More recent research even suggests that in contemporary entertainment media, scientists are portrayed in an almost exclusively positive light and often as heroes.

Scientists, academics and technologists depicted from the 1930s to the 1950s were portrayed as ‘heroes’ working to make the world a safer, better place: One free from disease (The Story of Louis Pasteur, 1936) or tyranny (The Dam Busters, 1954). These were largely propaganda films meant to inspire audiences during a period of economic depression, the war and its aftermath.

In most recent years, such films have tended to offer a warts-and-all depiction, interweaving the academic prowess of their subjects with complex emotional stories. Both Kinsey in Kinsey and Nash in A Beautiful Mind are portrayed as flawed, but brilliant, men.

The two films selected here examine men working in academia during the same period. One, whose name became part of the public vocabulary within weeks of a revolutionary publication, Kinsey, the other, Nash, remained comparatively unknown until the film version of his life was released.

A Beautiful Mind (2001)

Director: Ron Howard

Screenwriter: Akiva Goldsman

Starring: Russell Crowe (John Nash), Jennifer Connelly (Alicia Nash) and Paul Bettany (Charles)

Subject: American mathematician John Nash (John Forbes Nash, Jr, 1928–present)

Inspired by Sylvia Nasar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography A Beautiful Mind (1998) which is academic in tone, Goldsman’s screenplay echoes the themes but creates tensions by drawing out John Nash’s paranoid obsessions and mental breakdown. His schizophrenia is not treated as a quirky character trait or as crippling tragedy; Nash is seen dealing with this illness and to an extent overcoming it.

Producer Brian Grazer optioned the book after reading an excerpt in Vanity Fair magazine. Goldsman was selected as screenwriter and when Ron Howard came on board as director, he sought additional script changes to emphasise the love story between Nash and his wife Alicia (Jennifer Connelly). Dave Bayer, professor of Mathematics at Barnard College, Columbia University, was consulted on the mathematical equations that appear in the film.

Nash’s messy life is rendered simple through a seemingly straightforward narrative structure which offers a clear sense of him triumphing over adversity. The revelation of the

Sixth Sense-twist at the end, where it is revealed that Charles (Paul Bettany) is a figment of Nash’s imagination, forces the viewer to revaluate the film as a whole. The imaginary friends were an invention; yet it is unusual for schizophrenics to suffer from visual hallucinations, which are usually auditory. The change was a cinematic device to help the viewer see inside Nash’s mind. His schizophrenic delusions ensure that the film’s tension is retained, and viewers do not know what is real and what is imagined. As Akiva Goldsman noted, ‘that John and Alicia Nash responded well to the sprit was flattering to me, but I don’t pretend this is how John saw the world. This is expressing to an audience how John might have seen the world. I tried to make the delusional system more cohesive to the audience’ (quoted in Divine 2002: 71).

The film was criticised for it omission of his violence, homosexuality, and making no mention of the child he had with another woman, instead offering ‘a glossy example of how a troubled and troublesome life can be sanitised into a movieland saga’ (Kauffman 2002). Everyone involved in the making of the film repeatedly insists that they did not intend on making a bio-pic, that it is merely inspired by Nasar’s biography. The film reads more like a thriller than a life story. Goldsman continued:

The book is straight biography and an extraordinary one. Sylvia Nasar did an amazing job. But the movie version of A Beautiful Mind is not a bio-pic. God gave us, in the form of John Nash, an amazing architecture of a life. Genius, madness, Nobel Prize – you can’t do better than that if you’re looking for drama. I tried to hang on to that architecture scenes that would evoke the experience of the life John lived, but no literal scenes from his life, there’s very few of those. (Ibid.)

Yet according to Cynthia Rockwell, writing in Cineaste magazine,

The book delivers a John Nash who is arrogant, selfish, unkind and unrepentant – traits that are either removed from or made charming in the film. The film does not, for example, include the fact that Nash often belittled students and colleagues as stupid if they merely asked him to clarify something: the film instead gives us a few playfully arrogant quips intended to make Nash seem endearingly socially inept rather than cruel. (2002: 36)

The narrative of the film differs wildly from Nash’s actual life story with the filmmakers’ emphasis on conveying Nash’s mental illness, his schizophrenia and paranoia giving way to hallucinations and the imaginary friends. Nash never worked for the Pentagon; he worked between his Princeton and MIT years for the RAND corporation.

The hallucinations are shown as beginning whilst he is a student, whereas they occurred later when his wife was pregnant with their first child.

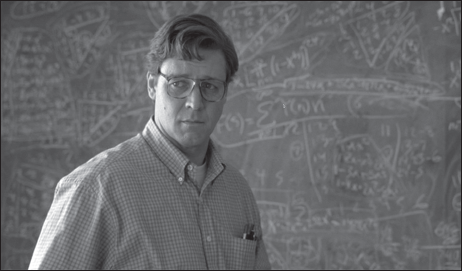

Russell Crowe as John Nash in A Beautiful Mind (2001)

A Beautiful Mind is a thoroughly American film, a fantasy, a triumph of individualism over adversity. Ultimately the film is best viewed as its makers have contended, as a spectacle inspired by, but not loyal to, the film of John Nash or his biography. (Rockwell 2002: 37)

Crowe did not meet Nash prior to filming; rather he worked from seventeen photographs. He did not want to see the seventy-year-old Nash, as he was playing him in his late twenties over five decades earlier. The physical changes caused by schizophrenia had a great impact on him.

The film never really explains how he won the Nobel Prize for Mathematics. The academic content is reduced to the equations on his classroom wall: so familiar from fictional descents-into-number-obsessive thrillers such as Pi (Darren Aronofsky, 1998) and The Number 23 (Joel Schumacher, 2007). Russell Crowe remarked, ‘Nash as he is now is not a true witness to who he was as a younger man. We would ask questions like, Did you ever smoke? And he would say no, and yet we know he smoked for several years. Did you ever have a beard? Not that I can recall. And we have photographs of him in Europe wearing a beard. From that point on, I realised the movie would be based on broader aspects of his life’ (quoted in Palmer 2002: 46).

Nash took no medication after 1970 but the filmmakers included scenes showing that he did, as they did not want to encourage the idea that schizophrenics can overcome their illness without it. The film’s moving speech at the Nobel Prize ceremony in 1994 was a Hollywood concept; he gave no such address. Further, his wife could not have been there; they had been divorced for many years, only remarrying the year the film was released.

Cynthia Rockwell continues:

The filmmakers could have avoided the criticism over authenticity had they merely changed the film’s title (which is probably the film’s only direct link to the book, after all). When a film is adapted from a book there are all kinds of extraordinary demands, about authenticity and loyalty, and when a film is adapted from a biography, those demands are even greater. The story is about a life actually lived, not one that is invented; therefore a certain measure of ‘reality’ is assumed. Biography, like documentary film, is assumed to represent fact objectively. The fact that the book’s author, Sylvia Nasar, once was a reporter – with an assumed allegiance to journalistic ‘fact’ – adds another layer of ‘authenticity’ to her ‘unbiased’ account, and another layer of responsibility for the filmmakers. Indeed in a recent interview with The Advocate, Nasar admitted that she was too confused by the concept of bisexuality and had too little evidence to form any real conclusions about Nash’s sexuality in her book. (Rockwell 2002: 37)

The film’s budget was $58 million, it took well over $300 milion at the world-wide box office and was well received by critics.

Director Ron Howard’s approach to the problem of the biopic is totally different from Michael Mann’s Ali. How do you make a mainstream movie out of the life of a man whose activity is almost entirely mental? Screenwriter Akiva Goldsman’s clever solution is to turn the story of a troubled academic into a Hollywood thriller. How? He makes things up. Howard’s movie is being touted as an Oscar contender – Hollywood loves these ‘triumph of the spirit’ sagas – but in ‘solving’ the dilemma of the biopic it’s turned a fascinating life into formula. (Ansen 2001)

Director: Bill Condon

Screenwriter: Bill Condon

Starring: Liam Neeson (Alfred Kinsey) and Laura Linney (Clara McMillen)

Subject: American biologist, professor of entomology, zoology and sexologist Alfred Kinsey (Alfred Charles Kinsey, 1894–1956)

In 1948 Alfred Kinsey published Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male, an academic study on male sexual thoughts and actions. He followed this up in 1953 with a book examining the sexual behaviour of women. The book was considered so shocking that his credibility was ruined and his funding withdrawn.

Kinsey was written and directed by the openly gay director Bill Condon, whose other bio-pics include Gods and Monsters (1997) about the film director James Whale and The Fifth Estate (2013) on Julian Assange. Condon has admitted, ‘I didn’t want to make the film exclusively about gayness. This would have been very much against the spirit of Kinsey’s own philosophy. He believed in a great variety of forms of sexuality’ (quoted in Grundmann 2005: 4).

The film’s focus is on the period leading up to the publication of Kinsey’s 1948 study through to his death in 1956. The first thirty years of his life are compressed into thirteen minutes within a flashback. Here he recalls key moments from his past that helped shaped the man he had become.

Condon based his screenplay in part on two biographies: James H. Jones’s Alfred C. Kinsey: A Public/Private Life (1997) and Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy’s Sex the Measure of All Things: A Life of Alfred C. Kinsey (2004). The two biographers offer contrasting conclusions about Kinsey’s work. Jones claims that Kinsey’s hands-on research along with an increasing personal interest in homosexuality compromised his findings whereas Gathorne-Hardy insists that Kinsey’s methods were ethical and scientific. The film’s position helped to redeem a man whose contribution to a greater understanding of sex, which ultimately led to the de-criminalisation of some acts, had been lost.

Its coverage of the harsher, darker sides of Kinsey’s character (his bisexuality, masochistic and voyeuristic practices) was commended by critics, but, as Roy Grundmann says, ‘flawed characters make for better bio-pics’ (2005: 5).

The film graphically displays Kinsey’s bisexuality, his marriage to liberated and liberating Clara ‘Mac’ (Laura Linney) and his affair with one of his researchers Clyde Martin (Peter Sarsgaard), who later has an affair with Clara, which Kinsey endorsed. Yet, according to Grundmann, the film omits

the fact that Kinsey recruited hundreds of ‘friends of the research’ (among them underground filmmaker Kenneth Anger, painters Audrey Avinoff and Paul Cadmus, and literati Glenway Wescott and Gore Vidal), who would eagerly put their address books, their porn collections, and their own bodies into the service of science. Neither does it mention the fact that Kinsey hired a gay photographer, Clarence Tripp, for the purpose of building a collection of two thousand cinematic studies of ejaculation. This is a shame, for Kinsey’s reliance on gay artists and gay men in general are direct proof that his brand of science by no means preceded the wonders he discovered, but got reshaped by the concrete possibilities he encountered in the course of discovering them. (2005: 7)

The film opens with a close-up black-and-white image of Kinsey being interviewed by Clyde. As the interview continues, it becomes clear that this is a training session as Kinsey coaches his researcher on how to phrase questions, encourage responses and be aware of body language. The initial interview then triggers extended colour flashbacks to his youth, courtship of Clara, marriage and university life, which brought him to this point.

His childhood, overshadowed by recollections of his puritanical father (John Lithgow) railing against sex, science and zippers, and the young Kinsey masturbating furiously shortly after advising a fellow scout of the sinful nature of the act. Rebelling against this strict Methodist upbringing he would become the world’s first expert on sexual behaviour. Another flashback shows his own awkward wedding night attempts at sex with his new bride, which leaves him ashamed and isolated. This triggers the desire to expose and understand the sex act within a variety of situations, both physiologically and psychologically.

Alongside the narrative drive of Kinsey’s life are interspersed direct-to-camera addresses of his research subjects, recounting their intimate sexual desires and practices. It offers frank and graphic accounts of sexual behaviour from the standard norm to the wildly deviant.

Kinsey himself is portrayed as a flawed teacher, and poor at the politics of an academic life. Yet his talent as an interviewer ensured that his subjects revealed their most personal thoughts and feelings. The boredom of research process is exposed; and the boundaries between sexual research and the experience become blurred. The attic of his house was used, the bed had a camera trained on it, and various people perform sexual acts there as research. Yet James Christopher writes that ‘Kinsey is the most unsexy film about sex I’ve ever seen. … That Condon manages to cram so much complexity and detail into this film is nothing short of astonishing’ (2005).

However, the film did have its detractors. Kinsey’s work, even sixty years on, is still problematic to some. Right-wing American writer Judith Riesman considered Kinsey a pervert and founder of the ‘homosexual movement’, dubbing him akin to Adolf Hitler and Saddam Hussein and calling for a boycott of the film. On Kinsey’s detractors, Condon said:

Kinsey is such an enduring cultural figure, so I didn’t want to leave out any of the stuff that makes people dislike him. I knew what the people who didn’t like him were going to say, because they had been demonising him for fifty years and over the years the charges have changed. In the 1960s, it was that he was a supporter of Planned Parenthood or abortion rights or homosexual rights or that he was an atheist. In the 1980s, they landed on this totally specious charge that he was somehow a proponent of paedophilia, or in fact a paedophile himself, which of course there’s no evidence for. Absolutely none. (Film4 2004b)

Condon also stated that the call for a boycott of the film ‘has been a godsend for us … I always knew that the fringe people wanted to demonise Kinsey. We’ve come so far since Kinsey, yet we are still in the same place. Puritanism is built into our DNA’ (quoted in Goodridge 2004). An early poster for the film was banned by London Underground. It depicted Liam Neeson standing in front of phrases from Kinsey’s reports including ‘orgasms’ and ‘masturbation’, the poster was withdrawn and replaced with less ‘offensive’ ones: ‘pleasure’ and ‘sexually’.

Poster for Kinsey (2005)

There were press reports on its world-wide certification. In Japan, it was the first film showing human genitalia to be shown uncensored, the country being known for its strict censorship policies in this area. In the US, Condon feared that the film would receive the hard-to-market NC-17, but the American ratings Board returned the film with a R rating. It was accompanied with a note saying ‘Thank you, we learned a lot.’

The resulting publicity from this call for a boycott and the censorship issues surrounding the film certainly helped the box office for this relatively low-budget ($10 million) British-funded film. It was nominated widely, and won awards at specialist (GLAAD) and mainstream awards. It was also very well received critically.

Nearly every scene crams in at least two or three handy plot or character points and a quotable line or two, further proving in the wake of his previous foray into the genre – the story of horror director James Whale,

Gods and Monsters – that Condon has a real knack for making biopics breathe. In fact, for all its daring and felicitous touches,

Kinsey is nevertheless the kind of ruthlessly conventional movie that seems designed to woo Academy Award nominations – though surprisingly the film has missed out on Oscar recognition. (Felperin 2005).

Further viewing

Creation (John Amiel, 2009); Charles Darwin (Paul Bettany)

A Dangerous Method (David Cronenberg, 2011); Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen) and Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender)

October Sky (Joe Johnston, 1999); Homer Hickam (Jake Gyllenhaal)