2

the history and evolution of postsecondary spanish language education in the united states

The key issue that departments of Spanish are currently facing is their change in status from a department of foreign language to something resembling a department of second national language and culture in this country.

—Carlos Alonso, “Spanish: The Foreign National Language,” 2007

The declaration that postsecondary Spanish language educators in the United States should consider Spanish a sort of national language, second only to English, comes approximately five hundred years after the first words of Spanish were spoken in what is now Florida, presumably by Juan Ponce de Leon and his crew in 1513. Less than forty years later, Spanish could also be heard by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo and his men on the coast of present-day California when they arrived in San Diego Bay in September 1542. Use of the Spanish language within the borders of the modern-day United States has a long and complicated history. This chapter seeks to not only trace the historical evolution of Spanish language education and the sociopolitical events and educational trends that influenced its trajectory, but also analyze the current state of Spanish in collegiate institutions. These data will shed light on recent trends in Spanish language curricula and programs, and on what the future augurs for subsequent generations of Spanish language educators, their students, their programs, and their institutions.

We begin this chapter with a brief summary of the history of Spanish language education from the arrival of the Spanish explorers in the New World to the integration of Spanish into postsecondary curricula throughout the United States in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to its current status in academia. Given the scope of this book, the present discussion focuses on the evolution of macroprogrammatic issues over time—such as enrollment trends, curricular foci, and societal perceptions—with only limited space dedicated to specific teaching methodologies.1 Nevertheless, certain pedagogical innovations and other relevant scholarship in related fields such as linguistics, psychology, and second-language acquisition are woven into the narrative when deemed pertinent.

spanish language education from contact to the nineteenth century

Though little detailed historical documentation is available, the teaching of Spanish most surely was undertaken for the first time in the Western Hemisphere by the Spanish clergy after having come into contact with the indigenous peoples of the Americas and having set up permanent settlements in the New World. As early as 1516, the Spanish monarchs and the Catholic Church expressed their desire to teach the indigenous people Spanish when Francisco Cardinal Jiménez (Ximenes) de Cisneros identified the teaching of Spanish as a crucial component of Spain’s colonization and Christianization of the New World.2 However, Sánchez Pérez observed that a formal, systematic, and enduring approach to Spanish instruction was not instigated for many years after initial contact between the Europeans and the indigenous peoples of the Americas, and “was spread and learned most often by way of ‘natural’ means.”3 Indeed, the current linguistic landscape of most of Central and South America is a testament to how indiscriminate and thorough this natural learning of Spanish was in supplanting indigenous languages, when not in competition with the languages of other colonial powers.

Within territory that would eventually fall under the rule of the United States, the teaching and learning of Spanish would develop differentially along two separate geographic axes in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: (1) the Eastern Seaboard and adjacent territories dominated by Anglophones from the original thirteen colonies, and (2) the southern and southwestern lands liberated from Spanish rule before annexation by the United States by purchase or by treaty. Unlike the lands of the American colonies, much of the southern and southwestern territory was already populated by Spanish-speaking mestizos and criollos when English-speaking Americans arrived.

Several individuals throughout the American colonial period identified the potential market for Spanish instruction, targeting clients seeking fruitful commercial relationships with Spain and its extensive colonies in the Western Hemisphere, such as Augustus Vaughn, John Clarke, and Garret Noel. Leavitt (1961, 123) identifies the Public Academy of the City of Philadelphia—that is, the University of Pennsylvania—as the first institution of higher education to identify the need for Spanish instructors in its 1749 Constitution. By 1766 Paul Fooks was installed as professor of Spanish and French at the Public Academy, while an Italian, Carlo Bellini, was charged with teaching French, Spanish, and Italian at William and Mary College in 1779. Nevertheless, the well-traveled and rather cosmopolitan Francisco de Miranda from Venezuela noted in his diary after visiting Harvard College in the 1780s that “it is extraordinary that there is no chair whatever of living languages,” a rather prescient observation that would be addressed in time.

spanish in the academy in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

In spite of these early initiatives at establishing Spanish systematically in university curricula, the teaching of Spanish at the postsecondary level in “a really serious way” (Leavitt 1961, 593) would not commence until 1815, when Abiel Smith bequeathed $20,000 to Harvard University for a professorship in French and Spanish. George Tickner and the poet Henry Longfellow were the first to fill the Smith Professorship, and they, along with subsequent Smith professors, had a profound impact on the direction and focus of Spanish teaching at the collegiate level that can still be felt today—namely, a concentration on literary texts written by authors from the Iberian Peninsula. In referring to the Smith professors, Spell (1927, 151) concludes that it would be difficult to accurately gauge “the influence these men . . . exerted on the development of Spanish teaching in the United States.”

The Harvard professors’ methodological focus, which placed a premium on the use of literary texts and literary analysis for language instruction, was so strong that institutions with even “the most utilitarian motives used texts whose purpose was to introduce students to the treasures of Spanish literature” (Spell 1927, 151). This bias in favor of Peninsular Spanish and Spanish literature and culture continued on into the 1900s and only started to recede toward the close of the third decade of the twentieth century, when the Harvard Council on Hispano-American was organized in 1929. By 1961, Leavitt (1961, 616) proclaimed that Latin American studies “are now firmly entrenched in the colleges and universities of the United States.” However, the dominance of literature in university curricula and faculty scholarship continues rather strongly to the present day (VanPatten 2015). Serious scholarly research and teaching within the fields of Hispanic linguistics and applied linguistics would not appear until many decades after Spell’s 1927 article.

Throughout the 1800s, Spanish instruction at institutions of higher education continued to spread, both in terms of the number of institutions teaching Spanish and in terms of the prestige given the language vis-à-vis instructors’ academic appointments and the acceptance of Spanish courses toward degree requirements. By 1832, at least fourteen institutions offered Spanish, and though many still employed instructors, several universities established similar professorships to the Smith Professorship at Harvard. Throughout the nineteenth century, many other universities, both public and private, introduced Spanish, and others began accepting Spanish courses to fulfill graduation requirements. The establishment of the Modern Language Association (MLA) in 1883 and the publication of the Modern Language Journal in 1916 provided additional evidence of the growing interest in the study of world languages in higher education, but more specifically the study of a language’s literary canon and high culture. The American Association of Teachers of Spanish was formed in 1917, and the first issue of its journal Hispania came out in 1918.

Notwithstanding the integration of Spanish at the most prestigious and best-known universities, Leavitt (1961) notes that the growth of Spanish teaching was not continuous and that interest was sporadic. He argues that if all American universities are considered, Spanish only rarely was part of the curriculum and in some cases was relegated to an extracurricular subject to be studied outside class, with no official credit being awarded. Leeman (2006) notes that in 1910 not one of the 33 percent of US colleges that required two to four years of modern language study accepted Spanish. Cook’s (1922, 276–77) indictment of Spanish as bereft of any cultural value within the educational context is indicative of prevalent biases against Spanish during this time: “German and French are the languages of great literatures as well as of science; Spanish, relatively speaking, is the language of neither.” Writing in 1927, Spell laments the fact that Spain seemed to monopolize the Spanish postsecondary curriculum as instructors directed students’ attention solely to the life, culture, and literature of the Spanish Peninsula, and those who traveled abroad “have sought Spain as their Mecca, not Spanish America”(Spell 1927, 158). He also hints at the irony that most of the graduate programs in Spanish at the time his article was published were offered by institutions in the East, far removed from lands formerly part of the Spanish Empire, where native Spanish could still be heard as a means of communication. Leeman connects racial prejudice to the sociocultural marginalization of Spanish speakers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, arguing that some feared that a further expansion in Mexico and the Caribbean would threaten the maintenance of the United States as a “white English-speaking nation” (Leeman 2006, 35).

territorial expansion in the nineteenth century: from majority to minority

By the early and middle nineteenth century, Spanish had been firmly established as the primary means of communication among longtime residents throughout the extensive Spanish territories along the southern and southwestern axis. The outbreak of revolutionary movements among many Spanish-American colonists in the early 1800s engendered sympathy for Spain’s subjects and broad interest in Spanish America among Anglo-Americans from the East (Spell 1927). Several events within a fifty-year period transformed sympathy and interest to massive migration as English-speaking Americans poured into lands formerly ruled by Spain but still populated by Spanish-speaking majorities, starting with the purchase of Louisiana in 1803 and Florida in 1819. The annexation of Texas in 1846, the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the discovery of gold in California in 1848, and the annexation of lands included in the Gadsden Purchase in 1853 served to further increase the contact of English and Spanish speakers and sparked Anglo-American interest in the prospect of economic benefit in these newly acquired lands and, consequently, in the Spanish language. Unlike the Anglophones striving to learn Spanish from the mid-eighteenth to the early nineteenth centuries along the Eastern Seaboard, who constituted the linguistic majority in their communities, those who flooded into lands recently liberated from Spanish rule were initially a linguistic minority, but they came from an ascending regional and international political superpower. In many cities and towns throughout the Southwest and West, Spanish-speaking majorities were completely replaced by English-speaking settlers within two or three generations, such that English became the majority language in much of the southwestern and western United States by the dawn of the twentieth century.

Field (2011, 6) points out that contact between speakers of diverse languages may be the result of conflict and the “apparently human urge to conquer, dominate, and expand ethnic or national frontiers.” To some degree, this seems to have been the case for Anglo-Americans in the nineteenth century as they moved across the continent with their culture and language in tow. Ironically, it was Americans’ perceptions of the Germans’ desire to conquer and dominate that led to reduced interest in the study of German following World War I. Though German had been the default foreign language—with its connection to science, psychology, and philosophy—Spanish enrollments at all levels increased as a result of the resentment many Americans felt toward the German language during and after World War I.

In spite of the drop in German enrollments and the increase in Spanish enrollments following World War I, and even World War II, Sánchez Pérez (1992) cites survey research conducted in the 1930s and 1940s (Leavitt 1936; Walsh 1947) indicating that Spanish might have been doing well quantitatively but not qualitatively: “In many places Spanish is relegated to second-class status and is not considered worthy as a requirement for other courses of study.”4 For most of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, foreign languages were thought of as tools for achieving greater depth in and enriched study of a particular field—such as literature, culture, psychology, and philosophy—and not as objects of study themselves akin to the modern study of linguistics or the acquisition of practical communicative ability. As such, one index of a language’s prestige within an institution was the number of academic programs that required students to achieve reading mastery as a prerequisite for advanced disciplinary study. For most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and even portions of the twentieth century, French and German were considered more academically prestigious languages because they provided access to works of the great German and French authors, philosophers, and scientists. As is demonstrated elsewhere, other sociocultural, ethnic, racial, and linguistic ideologies also exerted great influence on the assignment of prestige to different languages.

immigration and the persistence of utility in the twentieth century

The story of the Spanish language and its instruction within the borders of the United States took a distinct turn in the twentieth century. By the mid-1900s, few could argue that English was not the language of power, commerce, and governance across nearly all communities in the United States. The territorial borders of the continental United States had been solidified, and contact between Spanish and English in the United States no longer was due to territorial expansion and imperialism, strictly speaking, but rather national security, free trade, and, most important, foreign immigration. After the close of World War II, the onset of the Cold War, and Russia’s launch of Sputnik in 1957, the American government felt the need to improve education at all levels and in all subjects, including foreign languages, as a way to remain competitive internationally and as a way to effectively defend itself against communism (Heining-Boynton 2014). The National Defense Education Act of 1958 was the legislative manifestation of this angst and injected unprecedented amounts of tax money into schools at all levels.

However, as America’s standing as the preeminent economic, cultural, and political superpower became undeniable, it also became clear that America’s international status had severely undermined foreign language learning. English became a lingua franca worldwide, and the United States’ cultural and economic power reached into even the most remote villages of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. As such, Americans found less and less reason to learn other languages and monolingualism continued as the norm. A different sort of national security surfaced in the United States that might better be referred to as apathy. Many felt secure with their identity as citizens of the most powerful and influential country and as speakers of one of the most widely used languages in the world. Although some surely felt that the world’s desire to learn the language of the United States was a feather in its cap, Paul Simon (1980) famously bemoaned America’s entrenched monolingualism in his oft-cited The Tongue-Tied American: Confronting the Foreign Language Crisis. The relative calm that accompanied America’s apparent triumph over its perennial Cold Ward rival—Russia—was short-lived. The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on America, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, and the ensuing war on terror led the US government to, once again, address America’s linguistic deficiencies and to identify critical needed languages. Government agencies formed partnerships with universities to offer scholarships for students willing to engage in advanced study of critically needed languages such as Arabic, Chinese, and Farsi. As Field (2011) so accurately observed, conflict is one of the strongest motivators for language learning at the national level; nevertheless, national security may be the most ephemeral of motivations because armed conflicts on foreign lands in the modern era tend to dissipate in the public’s consciousness much faster than it takes most postpubertal adults to achieve functional proficiency in the second language.

An additional utilitarian motive for the teaching and learning of foreign languages, and Spanish specifically, is identified by Field (2011) as economic cooperation, or exploitation—depending on the power differential between nations. From the earliest evidences of Spanish instruction in the thirteen colonies, Spanish language learning has been connected to economic gain for the learner because it allows access to previously inaccessible markets. The rapid globalization of world markets in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries led to several free trade agreements, including the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994. Though hotly debated and quite controversial, this pact, along with other free trade agreements, made it more profitable for American companies to do business in other countries. As transnational American companies poured into Spanish-speaking countries—such as Mexico, Panama, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Colombia—the need for Spanish proficiency among domestic employees and employees stationed abroad became more acute. The rise of business Spanish courses in the United States is but one tangible example of how free trade agreements have affected the teaching and learning of Spanish. Sánchez Pérez provides a somewhat scathing conclusion from an outsider’s perspective regarding Americans’ interest in learning Spanish: “In the United States, what has most driven the learning of our language [Spanish] has been the reality and need for trade with Latin American countries. While aesthetic, literary, and even romantic motives cannot be discounted, they are not substantial enough, quantitatively or qualitatively, to attract the attention of Americans.”5

As the twentieth century came to a close, Spanish-speaking markets were not only made available abroad but also became increasingly viable domestically, with large numbers of Spanish-dominant consumers residing within the borders of the United States. The following observation made by Leeman (2006, 37) rings true, especially for Spanish in the United States during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: “Second-language ability is increasingly commodified as a job skill, rather than a symbol of education and cultural capital.”

From the bracero program of the 1940s and 1950s that provided American farmers with laborers from Mexico to the political refugees fleeing Cuba in the late 1950s and early 1960s and the economic refugees in the early 1980s, to the thousands of Puerto Ricans established along the Eastern Seaboard to the undocumented Mexicans and Central Americans who cross the southwestern border seeking greater economic opportunity, the twentieth century has been marked by large numbers of foreign-born, Spanish-speaking immigrants to the United States. As we noted in chapter 1, Hispanics make up the largest ethnic or racial minority in the US, and Spanish is the most commonly spoken language in American homes besides English, by a large margin. Several states have seen increases of more than 60 percent in the number of Spanish speakers in less than ten years (2005–13). These waves of Spanish-speaking immigrants have had a profound impact on several sectors of American society, not the least of which is education, particularly Spanish language education.

As the numbers of Spanish speakers in the last several decades of the twentieth century grew, Spanish quickly became the default foreign language course at all levels, from elementary to secondary to postsecondary. The MLA’s periodic survey of collegiate foreign language enrollments indicates that Spanish enrollments surpassed those of all other languages in approximately 1970. From 1985 to 2009, the gap widened between Spanish and the other languages so quickly that since 1995 Spanish enrollments have totaled more than all the other languages combined (figure 2.1), notwithstanding a slight dip in Spanish enrollments from 2009 to 2013. In like manner, the number of Advanced Placement examinations given by the College Board to high school students in Spanish language and Spanish literature between 1979 and 2014 increased from 4,378 to 152,962. In 1979 the two Spanish exams represented 46 percent of modern foreign language Advanced Placement exams given, while in 2014 this proportion had risen to 81 percent (figure 2.2). The logic for why many high school and university students opt for Spanish over other languages is sound: the likelihood of using oral Spanish in their day-to-day lives with native and Spanish-dominant speakers either at work or in the community regardless of location is much higher than it is with other languages. This practical, performance-based approach to language learning received scholarly support from movements in applied linguistics and foreign language education that enthroned communicative competence and proficiency as the hallmarks of second-language learning.

Figure 2.2World Language Advanced Placement Examination Totals, 1979–2014

Source: Data from Alan V. Brown and Gregory L. Thompson, “The Evolution of Foreign Language AP Exam Candidates: A 36-Year Descriptive Study,” Foreign Language Annals, June 17, 2016. © 2016 American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages; reprinted by permission.

changing demographics and diverse needs in the twenty-first century

As the country’s demographics have changed, with large numbers of immigrants arriving from Spanish-speaking countries, so too has the makeup of many of America’s schools. Many of the children of immigrant families that enrolled in elementary schools and high schools had limited, or no, English skills, and as a result they struggled to progress academically and even failed miserably, leading to disillusioned, disenfranchised, and disgruntled parents. These students’ language learning and cultural needs were addressed by a series of legislative acts—no doubt facilitated by the civil rights movement—passed by the US Congress throughout the 1960s and 1970s.6 Foremost among these, insofar as Spanish language education is concerned, were the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 and the Bilingual Education Act (Title VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act) of 1967.

These progressive pieces of legislation were designed to allow students with limited English skills to make use of, and even improve, their first language (Spanish) as a means of improving their second-language skills in English. From a cognitive, linguistic, and acquisition perspective, this approach seemed reasonable, grounded in sound second-language acquisition theory, and offered a practical solution to academic underachievement and failure among the thousands of schoolchildren from Spanish-speaking homes with limited proficiency in English. As a result, bilingual programs began sprouting up across the country in areas with large Spanish-speaking populations. One school in Miami—Coral Way Elementary School—was looked to as an example of how to run a successful bilingual program, where English-speaking students learned Spanish, but, more important for the Anglophone majority, where Spanish-speaking students learned English.

However, as Field (2011) notes, it became apparent rather early on that there were as many definitions of bilingual education as there were bilingual schools and that socioeconomic and sociocultural variables exerted great influence on learning outcomes, as did teacher expertise and commitment. Bilingual programs were initially portrayed as somewhat of a panacea for teaching migrant children English, but many stakeholders felt that these programs did not live up to their billing. Unfortunately, in many cases bilingual programs were only bilingual in name, given that the curricula, pedagogy, and culture at many schools were subtractive in nature and undermined maintenance of the first language. It was clear that what many in society wanted was for Hispanic, Spanish-dominant bilingual children to become English-dominant monolinguals as quickly as possible. The apparent failure of bilingual programs—coupled with strong political, economic, and social forces decrying illegal immigration—led to many English-only campaigns across the country. These movements seemed to devalue bilingualism specifically among Latinos, which in turn created a rather hostile environment in those US states that aggressively pursued English-only laws. Several states that had large conservative voting blocs and also had large Spanish-speaking populations—such as California, Arizona, and Texas—voted to dismantle traditional bilingual programs, leaving only remnants of the original models and severely limiting the use of students’ native language in the school setting.

The traditional approach to school-based foreign language learning, which delayed formal coursework until the secondary level and was oriented toward English-dominant monolinguals, became the norm for all but students with the most limited English proficiency. Rather than strengthening both of a bilingual child’s languages from the beginning of his or her school career to facilitate greater outcomes by high school graduation, traditional curricular models made Spanish-English bilinguals wait until their native language proficiency fell below the level of their second language, English, before allowing them to renew study in the first language, Spanish, at the high school level. Students’ bilingualism was essentially viewed as a liability to be dealt with and delayed rather than an asset to be capitalized on from the outset. A 1972 white paper published by the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese (1972, 19) stated, rather poignantly, that as an organization, it was compelled to reject “the embarrassing anomaly of a language policy for American education which on the one hand seeks to encourage and develop competence in Spanish among those for who it is a second language, and on the other hand, by open discouragement, neglect, condescension, destroys it for those who speak it as a mother tongue.”

Ruiz (1990), who found that ethnic languages for minority-language populations are construed as problematic, identified the underlying ideology and clear paradox exposed by this approach to Spanish, observing that foreign languages for majority-language populations are seen as resources. Correa (2011, 315) states this quite succinctly: “Spanish enjoys different status depending on who the learner is (FL [foreign language] or HL [host language]).”

Not surprisingly, this subtractive—or at the least delayed—approach failed to produce satisfactory results because many bilingual students, in spite of perfect mastery of conversational English, struggled to acquire academic registers of English and Spanish and continued to underachieve academically. Many Spanish-speaking Latino students came from socioeconomically underprivileged families with little social capital. These students also struggled emotionally and socially at school, as many felt that their bilingual and bicultural identity were to be apologized for and dismissed rather than highlighted and celebrated. In some cases, linguistic biases harbored against Spanish-dominant Latinos in the United States represented only the surface of deeper racial and ethnic prejudices in the country.

The civil rights movement and the tireless efforts of prominent activists like César Chávez made great strides in imbuing the Mexican-American identity, language, and culture with pride. But it was not until much later that the presence of Hispanic, Latino, and Chicano students in traditional courses on Spanish as a foreign language resulted in widespread curricular change. In the 1990s and early 2000s, more and more Spanish language educators at the secondary and postsecondary levels were confronted with nearly fully bilingual students in their beginning classes. These students had developed solid receptive and fairly strong productive abilities in Spanish in their homes and communities as children. As their numbers increased, it became apparent rather quickly that these students (1) represented a very diverse group linguistically and culturally, (2) possessed linguistic and cultural competence that was quantitatively and qualitatively different from their monolingual Anglo-American classmates, and (3) required an alternative pedagogical approach catered to their needs. The term heritage or native was used to refer to these students, given their familial and childhood connections to the language, culture, or both, and courses were developed to address their needs. Textbooks were written especially for this population (Marqués 2000; Roca 1999), entire curricula and academic programs were designed (Beaudrie 2011), and a flourishing research program within applied linguistics was born (Beaudrie and Fairlough 2012).

Today, throughout the United States, collegiate Spanish language curriculum designers are confronted with incoming students at all levels but, quite ironically, relatively few that would be considered true beginners. In fact, it is safe to say without fear of misrepresentation that the large majority of students who enroll for the first time in any level of Spanish at a given tertiary institution, either as incoming freshmen or as transfer students, have previously studied the language formally, either in high school or at other postsecondary institutions. In many cases this holds true for introductory, first-year, first-semester courses, such as the proverbial Spanish 101. At the University of Kentucky (UK) from 2008 to 2016, the average share of Spanish 101 students with no high school Spanish was 24 percent, while the average proportion with two or more years of high school Spanish was 74 percent. These realities have led many programs, including UK’s, to create courses designed for “false beginners” that allow them to take only one course that equates to two semesters of the elementary language sequence. Indeed, the nature of Spanish 101 insofar as classroom pedagogy and language use are concerned would not strike an outside observer with no Spanish ability as a true beginning-level class. Although heritage students’ exposure to Spanish outside class may exceed their in-class exposure, traditional students may have very little contact with the language. The consequences of this disparity and the wide diversity of student abilities in Spanish at the postsecondary level have ramifications for the establishment of appropriate curricular-level structures; the design of accelerated, high beginner / intermediate, intensive, and heritage classes; the assessment of students’ abilities; the specification of programmatic student learning outcomes; and the deployment of classroom instruction.

pedagogical progress and the progressive expansion of spanish curricula

Since Spanish was first taught formally in Philadelphia in the mid-1700s, postsecondary Spanish curricula have undergone notable changes, despite a strong undercurrent of tradition. Many of these changes reflect trends in teaching methodologies, scholarly research in linguistics and second-language acquisition, and reconceptualizations of higher education and its goals. In this section, we briefly review these major trends, citing the results of our own analysis of several university course catalogs during the mid–twentieth and early twenty-first centuries as a means of systematically charting the growth of undergraduate course offerings and program configurations.

During much of the nineteenth century, Spanish language teaching was considered an intellectual exercise consisting of grammatical analysis and cross-linguistic translation, both of which facilitated analysis of literary masterpieces by prominent Spanish authors. Reading and writing were the preferred modalities, and grammatical and lexical accuracy were emphasized. In a typical college-level Spanish course in the 1800s in the United States, the medium of instruction was English, not the foreign language, and the development of students’ extemporaneous oral ability was not the focus. Many nonnative Spanish professors, potentially including some holders of the Smith Professorship at Harvard, would have struggled to conduct literary and grammatical analyses exclusively in spoken Spanish.

By the end of the nineteenth century, a reform movement in language teaching arose that looked to the first language and naturalistic acquisition as the model to follow in teaching second languages (Richards and Rodgers 2001). The Direct Method, as it was called, focused on oral communication reflective of daily communicative tasks, placed a premium on mastery of the sound system, and prescribed exclusive use of the target language during class. This approach to classroom language learning garnered many supporters and caught on well in private language schools with highly motivated learners in small classes, but failed to achieve the same success in public school classrooms with large groups of adolescents or even university students. With generally unsatisfactory learning outcomes in foreign language classes, the 1929 Coleman Report represented the culmination of a nationwide study that sought to identify reasonable goals for foreign language education in the public school system. The report recommended that a more realistic approach to language learning would be to focus on developing students’ reading ability, rather than trying to incorporate the time-consuming and exhausting techniques of the Direct Method.

The methodological pendulum would swing back again in the direction of naturalistic approaches after World War II, as government agencies realized that functional oral-aural interpersonal skills in critical foreign languages were a rarity among nonnative military personnel and civil servants alike. The Army Specialized Training Program was born out of this need, and was boosted by theoretical support from B. F. Skinner’s well-known approach to the analysis of human behavior—including language and language learning—called, simply, behaviorism. The theoretical foundation of behaviorism hinged on the organizing principle of stimulus–response psychology and led to an academic adaptation called the Audio-Lingual Method, which prioritized oral language, memorization and mimicry, and pronunciation, while demanding impeccable grammatical accuracy. In time, it too began to fall from grace after Noam Chomsky’s (1959) sharp critique of Skinner’s (1957) Verbal Behavior. Chomsky’s (1965) insights gave rise to modern linguistics and provided theoretical models for the structure, representation, and acquisition of language, all of which represented a significant departure from the structuralist tradition of the early to middle twentieth century. Although Chomsky criticized Skinner’s work, Dell Hymes (1966) did the same to Chomsky’s, finding several tenets of Chomsky’s theory of language competence deficient. Hymes argued that a speaker’s ability to use language in real time with the constraints imposed by situational factors demanded a broader conceptualization of language ability that transcended strict grammatical competence and captured what he called communicative competence. From the theoretical foundations laid by Chomsky and Hymes, scholars interested in language learning, such as Corder (1967), began to systematically study the acquisition of second languages, considering it a qualitatively different enterprise than the process by which infants learn their first language. The study of second-language acquisition was established as a scholarly field in its own right, and began to inform classroom pedagogy.

At the same time that researchers, teachers, and students’ perspectives on language teaching and learning were undergoing a transformation, so too was American higher education. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the numbers of young people in the United States who attended college began growing rapidly. A university education was not just for the social and economic elite who came from privileged backgrounds but was also made accessible to the working and middle classes of society (Bok 2006). As such, a college education was not solely to stimulate reflection and broaden students’ intellectual horizons or to develop an informed and civically active citizen, but rather to equip him or her with knowledge and skills that would lead to gainful employment. Heining-Boynton (2014, 143) notes that, by the mid-1970s, “students demanded real-world relevance in all of their college courses” and “enrolled in courses that they believed would help them in their jobs and careers.” This growing sentiment among college students that valued practical and even vocationally oriented curricula, coupled with developments in second-language acquisition, triggered an explosion of new courses in Spanish programs.

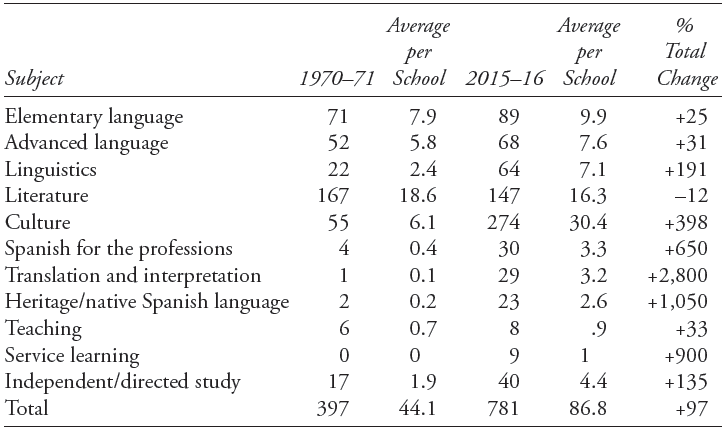

A strictly textual and quantitative analysis of selected American universities’ undergraduate Spanish course titles and course descriptions substantiates this trend. The course catalogs of nine prominent universities were studied longitudinally at regular intervals to determine how postsecondary Spanish course offerings have evolved over time. Academic years 1970–71 and 2015–16 were chosen as points of comparison because 1970–71 was the first year in which all nine schools’ catalogs were available for analysis and, given the use of modern conventions, for the reporting and publication of course titles and descriptions. Table 2.1 includes the total number of courses for each category, along with the average per school and the percentage change from 1970–71 to 2015–16. Overall, the total number of undergraduate courses offered across all schools nearly doubled, from 397 to 781. The subjects that saw the greatest increase were, in descending order, courses in translation and interpretation, heritage/native Spanish language, service-learning, and Spanish for the professions, from twenty-eight-fold (translation and interpretation) to six-and-a-half-fold (Spanish for the professions). Culture increased nearly fourfold, and it added the most courses in raw numbers (219), while linguistics and independent and directed study also saw their numbers more than double. The only area with fewer courses in the 2015–16 catalog than appeared in the 1970–71 catalog was literature, which fell 12 percent, from 167 to 147 courses. Nevertheless, when culture and literature are combined, they total 421, more than all the other nine categories combined (360). As such, courses categorized as literature and culture continue to dominate the undergraduate curriculum, with the percentage of culture courses rising dramatically from 1970–71 to 2015–16. In spite of Irwin and Szurmuk’s (2009) conclusion that Spanish programs have been less willing, or able, than German and French programs to adopt a cultural studies approach to postsecondary language education, our course catalog analysis seems to indicate that changes are indeed afoot, at least among these nine Spanish programs.

the need for change and the intransigence of tradition

Although our analysis of university Spanish curricula appears to paint a picture of progressive evolution and positive transformation, the actual situation is much more complex and nuanced. The wide variety of courses that have surfaced in the course catalogs during the second half of the twentieth century indicate the need for change insofar as course offerings were concerned, most likely due to student demand, administrative mandate, and advocacy from selected members of the faculty. Yet the fact that a course appears in a catalog gives no indication of whether it is taught each term or how many sections are available, or what the academic profile and rank of those who teach them might be, or whether the courses are coherently and cohesively integrated into an academic program of study with clear learning outcomes, or how well they match the research, training, and pedagogical inclinations of the majority of the professoriate. Many collegiate Spanish programs maintain a two-tiered approach to formal language learning, in which lower-level elementary language instruction has been programmatically and culturally separated from upper-level courses in literary, cultural, and linguistic studies. Although the lower-level language courses are often taught by part-time, adjunct, or graduate student instructors, in many universities the upper-level courses appear to be the domain of tenured or tenure-line faculty. This comes in spite of repeated calls by scholars in applied linguistics, foreign language education, and instructed second-language acquisition for the eradication of this longstanding configuration and for a more equitable distribution of undergraduate courses among instructors of all ranks. All this must be placed within the broader sociocultural and socioeconomic context in American higher education, in which the humanities, and foreign languages more specifically, are under pressure to “express a renewed sense of value” (Norris and Mills 2014, 1).

The long-standing programmatic bifurcation of language departments, in which lower-level courses focus on the development of day-to-day conversational language and upper-level courses focus on the reading and analysis of literary texts, reflects a deeper intellectual division in language departments throughout the academy. At the close of the twentieth century, Bernhardt (1998, 51) concluded that postsecondary language teaching has experienced, and continues to experience, a sort of schizophrenia: “The tension between the traditional, humanities-based, reading-oriented study of belles lettres and views advocating functionality and oral proficiency; the paradoxical image of language as part of the humanities but simultaneously in the service of government and the military; the social problematic of maintaining and valuing a cultural identity while encouraging people to assume another; and the economics of promising in a short term what can be delivered only in the long term.”

The tension many departments feel between developing a functionally oriented curriculum that would facilitate students’ acquisition of interpersonal, primarily oral, proficiency—as compared with more academic, primarily written, competencies—is felt nowhere stronger than in Spanish programs. Added to this tension are the “fissure between peninsularists and Latin Americanists” (Irwin and Szurmuk 2009, 44), the contested displacement of traditional literary approaches in favor of a cultural studies focus (Irwin and Szurmuk), and the apparent hesitance among both parties to accept that “they are responsible for teaching and producing scholarship about an increasingly national cultural reality rather than a foreign one” (Alonso 2007, 225). Irwin and Szumurk make a strong argument for the elevation of US Latino studies, Mexican studies, and Latin American studies within curricular hierarchies, at the expense of Spain and Peninsular studies, anecdotally noting that they are not familiar with any department with more Mexicanists than Peninsularists. Given the ubiquity of Spanish and Spanish-dominant speakers in US society, many of whom are of Mexican and Mexican-American heritage, students are attracted to Spanish because of the perceived utility for their future professional and personal lives, as opposed to their intellectual and academic lives.

Though many university students see the practical benefits of language study, they appear to be uneasy limiting their choice of major solely to language, and thus they often combine their language major with another major. A recent MLA report, “Data on Second Majors in Language and Literature, 2001–2013,” revealed that—not surprisingly—the number of foreign languages, literatures, and linguistics second majors surpassed the number in any other discipline within the sciences or humanities. Additionally, among all disciplines included in the US Department of Education Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, foreign languages, literatures, and linguistics had the highest rate of second majors as a percentage of total majors, at 38.6 percent in 2013. In the case of Spanish language and literature, second majors made up 48.3 percent of all Spanish majors, while many other languages had even higher proportions—Romance (82.4 percent), Italian (60.6 percent), French (54.7 percent), and German (50.1 percent). Probably the most telling statistic included in the MLA report came from the Humanities Departmental Survey of 2012–13, which found that 61 percent more minors (49,200) had been completed in languages other than English than had majors (30,240). In sum, students are increasingly pairing their language studies with studies in other disciplines, an implicit sign of academic pragmatism.

The curricular and programmatic manifestations of this intellectual struggle between pragmatism and intellectualism go beyond the well-known, two-tiered structure of many programs and may influence the identification of coherent student learning objectives overall. Byrnes, Maxim, and Norris (2010) identify two overarching learning goals that many foreign language programs espouse: (1) to acquire intellectually meaningful cultural knowledge about the pertinent areas and the peoples who speak the foreign language, and (2) to acquire the ability to use the foreign language (FL) effectively across a variety of contexts. However, many contemporary FL programs struggle to operationalize concrete and coherent learning objectives that would guide syllabus design. Byrnes, Maxim, and Norris (2010, 4) offer the following detailed and rather compelling explanation as to why this might be:

Among the results of this unresolved dilemma are bifurcated programs that relegate largely content-indifferent and content-underspecified and textbook-driven language instruction to roughly the first four semesters of study and that shift to largely language-indifferent or language-underspecified and faculty interest-driven content instruction in the remaining course offerings that pursue their cultural studies mission. With both programmatic halves existing in a nonarticulated relationship toward each other, the one undisputed characteristic of any successful FL acquisition to advanced capacities—namely, its long-term cumulative nature—remains unaddressed. As a consequence, collegiate FL studies departments are unable to create statements of valued and realistic learning outcomes for each of the major stages of their undergraduate programs in the humanities.

Foreign language curricula often reflect tradition as well as faculty interests and training. In practice, and even in theory, many academic programs do not map out a clear pathway to meaningful linguistic and cultural competence in the second language over the span of their college career.

As we observed in chapter 1, the 2007 MLA white paper called for fundamental changes to curricular and programmatic structures that seemed to perpetuate the two-tiered model. In order to achieve deep translingual and transcultural competence among students, the committee recommended the inclusion of more faculty trained in applied linguistics, greater collaboration between faculty of all disciplines and ranks, and the involvement of senior faculty in the teaching of lower-level courses. Soon after the publication of the Ad Hoc Committee’s report, the Teagle Foundation published a report concerning the state of the undergraduate major in language and literature. The Teagle Report (MLA 2009) reaffirmed the importance of language, literacy, and literature, while echoing much of what appeared only two years earlier, namely, greater collaboration among colleagues of all disciplines, greater efforts at achieving seamless articulation across levels, and greater accountability vis-à-vis the use of learning outcome measures.

VanPatten (2015) voiced unequivocal criticism of many foreign language departments for the lack of applied linguists, or what he called language scientists. The casual use of “language departments,” he argues, to describe departments that house non-English disciplines presupposes that they are made up of language experts—an assertion he refutes. VanPatten (2015, 4) claims that specialists in literary and cultural studies are not trained during graduate school, or even during their entire careers, to understand the intricacies of language and language acquisition: “The point is simply that the vast majority of scholars populating academic ‘language’ departments are not experts in language or language acquisition.” He presents findings from his analysis of the specialty areas of faculty from several Spanish and French departments at well-known research-intensive universities—six from the West Coast, six from the East Coast, and an additional fifteen primarily from the Midwest. VanPatten found that an overwhelming majority of faculty members specialized in literary and cultural studies, as compared with linguistics, language acquisition, or other disciplines. In Spanish the rate of professors with expertise in literary and cultural studies was 76 percent among the Midwestern institutions and 90 percent among the six prominent West Coast schools. Even in 2015, faculty members who specialized in literary and cultural studies continued to represent a large majority of collegiate faculty, a reality that VanPatten claims may have had detrimental consequences.

A fairly recent article by Hertel and Dings (2014) aimed at assessing the extent to which the 2007 MLA report had affected the state of the undergraduate Spanish major. The authors designed a survey based on the recommendations from the MLA ad hoc committee and distributed it to 400 faculty members, with 104 completing the survey. The responses to questions regarding the types of courses offered and the number and nature of required courses indicated that literature courses represented the core of the curriculum. Over two-thirds of institutions (69 percent) required three or more literature courses, while only a quarter (25 percent) did so for advanced language courses. Moreover, nearly all institutions (98 percent) represented by the survey respondents offered a course giving an introduction to literature, and 68 percent required it. In the case of linguistics, the introductory course was offered at 68 percent of institutions but was only required by 30 percent. Courses on Spanish for specific purposes, such as business Spanish and translation, were the least-offered and least-required courses. Only 28 percent of institutions offered specific concentrations within the major, while the other 72 percent had a general track allowing students to take a variety of courses in different disciplines. Most institutions (70 percent) required 30–36 credit-hours of coursework to complete the major, and only 18 percent indicated that the completion of an experience of study abroad was required. Participants’ responses varied with regard to the extent to which the MLA report influenced program requirements and offerings. Some respondents felt that the reports had exerted influence on their programs, while others were quite resistant to the report, and still others voiced frustration with their colleagues’ resistance. Finally, faculty members rated study abroad as the most important experience for students, at 4.58 out of 5, with advanced grammar a close second, at 4.39—ostensibly indicating a desire for improved language skills, among other abilities. Introduction to literature was rated at 4.36, and introduction to linguistics was rated at 3.62.

conclusion

By the time the formal teaching of Spanish made its way into the higher education system of the Anglo-American colonies, it had already been firmly established as a commonly used medium of communication in lands claimed by the Spanish crown in the southern and southwestern portions of the present-day United States. Many scholars consider the establishment of the Smith Professorship in French and Spanish at Harvard as a watershed moment in the teaching of Spanish in higher education, because it elevated Spanish and Spanish language literatures and cultures to subjects worthy of serious study. Yet the status of Spanish in university curricula did not follow an unbroken, linear ascent in the society dominated by Anglo-American culture. Geopolitical events such as armed conflict, commercial trade, and foreign immigration have all influenced the teaching of Spanish, as have paradigm shifts in linguistics and applied linguistics. Spanish has become the second-most-commonly spoken language in the country and the most commonly taught second language in America’s colleges and universities, with learners coming from a wide variety of proficiency profiles and sociolinguistic backgrounds. In order for Spanish instruction in the twenty-first century to flourish in the academy, deeply entrenched curricular and programmatic structures must be updated, ethnic and racial stereotyping of native-speaking populations must be addressed, effective pedagogies and realistic learning outcomes for all learners must be identified and implemented, and utilitarian and humanistic approaches to curriculum design must be seamlessly interwoven to achieve enduring translingual and transcultural competence. From our own analysis of course offerings and from research conducted by Hertel and Dings (2014) and VanPatten (2015), it is apparent that though change may be afoot in Spanish language departments, it moves at a slow pace and “without significantly upsetting the status quo” (Irwin and Szurmuk 2009, 52).

reflection questions

1. In your view, what criteria must be met for a language to officially be declared a second language at the local, regional, or national level? Does Spanish meet these criteria in your local community? What about regionally and nationally?

2. What social, economic, and cultural circumstances made the replacement of indigenous languages by Spanish so complete across such a large expanse of territory, from northern Mexico to southern Argentina, with very few exceptions? Why has English become such a globalized language and the lingua franca in so many areas of transnational intercourse?

3. What other major geopolitical events during the twentieth century influenced the teaching and learning of Spanish or other languages, in the United States?

4. Identify the pros and cons of learning a second language solely for instrumental, utilitarian reasons, such as to get a job or a raise, as well as the implications for classroom teaching and learning.

5. What might have caused the slight downturn in Spanish enrollments at the university level from 2009 to 2013? To what extent should Spanish language educators be concerned?

6. Regardless of your personal stance, articulate arguments that can be made for and against English-only legislation in the United States. What documents and services would most likely only be made available in English? How might English-only legislation and the discourse surrounding it affect bilingual education programs for minority children and foreign language programs for language majority students at the secondary level? What implications are there for university foreign language programs?

7. In some Spanish departments, there are deep divisions, and even resentment, between faculty members trained in literary and cultural studies and those trained in linguistics, applied linguistics, and foreign language education. How are these manifest in terms of the curriculum and programmatic configurations, and how might such territorialism be minimized?

8. In the appendix, we describe several data sets that have informed our analysis of Spanish language curricula at the postsecondary level in the twenty-first century, but we realize even these only paint a partial picture. Assume that you could access any relevant data regarding Spanish language teaching and learning at the university level, and then name three data sets that would shed further light on university Spanish language education. How would you analyze these data, and what would you expect to find? Would there be any clear curricular or programmatic implications?

pedagogical activities

1. With a partner, begin to roughly outline an ideal undergraduate Spanish curriculum for either a small, selective liberal arts college with 1,500 to 5,000 students or a large, research-intensive public school with 15,000 to 30,000, or any other type of institution, by completing one or all of the following tasks:

a. Draft a short, one-paragraph mission statement with three to five broad goals from which more specific student learning outcomes could be derived.

b. How many credit-hours will be required, and at what level(s)? Will there be any core courses, and will non-Spanish courses be allowed? Will there be a capstone project, experience, or education abroad trip required, or even an exit exam with a minimum level of proficiency?

c. Without specifying the title of each course, identify the types of courses offered and how many of each category will be required.

d. What programs of study will be available to students—for example, major with various tracks, minor with various tracks, teaching certification/licensure, translation/interpretation certificate?

e. What will the professional and demographic makeup of instructional staff be?

2. Conduct an analysis of your department’s curriculum and program by completing one or all of the following tasks:

a. Review the résumés of all full-time faculty and categorize them according to the discipline in which they received their highest academic degree and their appointment status (e.g., tenured/tenure-line, lecturer, visiting professor, full-time instructor, part-time adjunct). What categories did you use? Which category had the greatest number of instructors? Calculate percentages for each category.

b. If possible, determine how many students in a given semester are taught by instructors of different academic rank and contractual status (e.g., full professor, associate, assistant, lecturer, part-time adjunct, graduate student instructor, etc.) and the level of the courses taught (first-year beginning language, fifth-semester advanced grammar/composition, third/fourth-year introduction to literature/linguistics, etc.). Describe any trends that you discover.

c. Using the same disciplinary categories from 2a above, categorize all course offerings in the Spanish Department and calculate a percentage. Compare the percentage from 2a to 2c, and explain the match or mismatch.

d. Identify at least three additional courses that are not currently taught that you feel merit inclusion in the departmental offerings, and explain why.

e. Where feasible, contact either departmental or college-level administrators to request the total number of Spanish majors and majors from two other disciplines not in the humanities, such as biology, psychology, and business. In the case of the Spanish majors, request that they be broken down by primary/single majors, primary/double majors, secondary/double majors, single minor, double minor. What trends are detectable in the data across disciplines and within the Spanish major, and what might they indicate?

notes

1. Among the many historical overviews of second language teaching methodologies available for interested readers, we recommend Richards and Rodgers (2001), Grittner (1990), and Mitchell and Vidal (2001).

2. Readers are encouraged to consult Spell (1927), Leavitt (1961), and Sánchez Pérez (1992, chap. 5) for in-depth accounts of the history of Spanish teaching in the United States, from the arrival of the Spanish to the early and middle twentieth century. Heining-Boynton’s (2014) review provides much less detail of the early years of Spanish instruction in the US and throughout the nineteenth century, but it does include a more holistic perspective on issues of current relevance that are not accessible in other comprehensive reviews such as Doyle (1925) and Nichols (1945). Leeman (2006) also provides a history of the teaching of Spanish in the US with an eye to language ideology and the status of Spanish in the academy. Our review relied heavily on Heining-Boynton, Leavitt, Sánchez Pérez, and Spell.

3. Original Spanish: “Se expandía y aprendía sobre todo por medios ‘naturales’” (Sánchez Pérez 1992, 250).

4. Original Spanish: “En muchos centros el español se deja en segunda fila o no se contempla como ´requirement´ para otros estudios” (Sánchez Pérez 1992, 302).

5. Original Spanish: “En los Estados Unidos es la realidad y la necesidad del intercambio comercial con las naciones Hispano-Americanas la que ha promovido y empujado el aprendizaje de nuestro idioma. No se excluyen razones estéticas, literarias y hasta románticas, pero éstas no son lo suficientemente sustantivas ni cuantitativas para que el español atrajese la atención de los norteamericanos” (Sánchez Pérez 1992, 305).

6. See Field (2011, chap. 6) for further discussion of legislative acts that influenced bilingual education.

references

Alonso, Carlos J. 2007. “Spanish: The Foreign National Language.” Profession 2007, 218–28.

American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese. 1972. “Teaching Spanish in School and College to Native Speakers of Spanish.” Hispania 55: 619–31.

Beaudrie, Sara. 2011. “Spanish Heritage Language Programs: A Snapshot of Current programs in the Southwestern United States.” Foreign Language Annals 44, no. 2: 321–37.

Beaudrie, Sara, and Marta Fairclough, eds. 2012. Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States: State of the Field. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Bernhardt, Elizabeth B. 1998. “Sociohistorical Perspectives on Language Teaching in the Modern United States.” In Learning Foreign and Second Languages: Perspectives in Research and Scholarship, edited by Heidi Byrnes. New York: MLA.

Bok, Derek. 2006. Our Underachieving Colleges: A Candid Look at How Much Students Learn and Why They Should Be Learning More. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brown, Alan V., and Gregory L. Thompson. 2016. “The Evolution of World Language AP Exam Candidates: A 36-year Descriptive Study.” Foreign Language Annals 49, no. 2: 235–51.

Byrnes, Heidi, Hiram H. Maxim, and John M. Norris. 2010. “Realizing Advanced FL Writing Development in Collegiate Education: Curricular Design, Pedagogy, Assessment.” Modern Language Journal 94: 1–221.

Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic Structures. New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

———. 1959. “Reviews: Verbal Behavior by B. F. Skinner.” Language 35, no. 1: 26–58.

———. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cook, William. 1922. “Secondary Instruction in Romance Languages.” School Review 30, no. 4: 274–80.

Corder, Stephen P. 1967. “The Significance of Learners’ Errors.” International Review of Applied Lingustics 5: 161–70.

Correa, Maite. 2011. “Advocating for Critical Pedagogical Approaches to Teaching Spanish as a Heritage Language: Some Considerations.” Foreign Language Annals 44, no. 2: 308–20.

Doyle, Henry G. 1925. “Spanish Studies in the United States.” Bulletin of Spanish Studies II, 163–73.

Field, Frederic. 2011. Bilingualism in the USA: The Case of the Chicano-Latino Community. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Grittner, Frank. 1990. “Bandwagons Revisited: A Perspective on Movements in Foreign Language Education.” In New Perspectives and New Directions in Foreign Language Education, edited by Diane W. Birckbichler. Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Company.

Heining-Boynton, Audrey L. 2014. “Teaching Spanish Pre K–16 in the US: Then, Now, and in the Future.” Journal of Spanish Teaching 1, no. 2: 137–53.

Hertel, Tammy J., and Abby Dings. 2014. “The Undergraduate Spanish Major Curriculum: Realities and Faculty Perceptions.” Foreign Language Annals 47, no. 3: 546–68.

Hymes, Dell H. 1966. “Two Types of Linguistic Relativity.” In Sociolinguistics, edited by William Bright. The Hague: Mouton.

Irwin, Robert, and Mónica Szurmuk. 2009. “Cultural Studies and the Field of ‘Spanish’ in the US Academy.” A Contracorriente: A Journal of Social History and Literature in Latin America 6, no. 3: 26–60.

Leavitt, Sturgis E. 1936. “The Status of Spanish in the South Atlantic States.” Hispania 19, no. 1: 37–40.

———. 1961. “The Teaching of Spanish in the United States.” Hispania 44, no. 4: 591–625.

Leeman, Jennifer. 2006. “The Value of Spanish: Shifting Ideologies in United States Language Teaching.” ADFL Bulletin 38, nos. 1–2: 32–39.

Marqués, Sarah. 2000. La Lengua que Heredamos: Curso de Español para Bilingües. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Mitchell, Cheryl B., and Kari E. Vidal. 2001. “Weighing the Ways of the Flow: Twentieth-Century Language Instruction.” Modern Language Journal 85, no. 1: 26–38.

MLA (Modern Language Association). 2007. “Foreign Languages and Higher Education: New Structures for a Changed World.” www.mla.org/Resources/Research/Surveys-Reports-and-Other-Documents/Teaching-Enrollments-and-Programs/Foreign-Languages-and-Higher-Education-New-Structures-for-a-Changed-World.

———. 2009. “Report to the Teagle Foundation on the Undergraduate Major in Language and Literature: Executive Summary.” www.mla.org/pdf/2008_mla_whitepaper.pdf.

———. 2015. “Data on Second Majors in Language and Literature, 2001–2013.” www.mla.org/Resources/Research/Surveys-Reports-and-Other-Documents/Teaching-Enrollments-and-Programs/Data-on-Second-Majors-in-Language-and-Literature-2001-13.

Nichols, Madaline W. 1945. “The History of Spanish and Portuguese Teaching in the United States.” In A Handbook of the Teaching of Spanish and Portuguese, with Special Reference to the Latin America, edited by Henry G. Doyle. Boston: D. C. Heath.

Norris, John M., and Nicole Mills. 2014. “Innovation and Accountability in Foreign Language Program Evaluation.” Innovation and Accountability in Language Program Evaluation, edited by John M. Norris and Nicole Mills. Boston: Cengage.

Richards, Jack C., and Theodore S. Rodgers. 2001. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge.

Roca, A. 1999. Nuevos Mundos: Lectura, Cultura y Comunicación, Curso de Español para Bilingües. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Ruiz, Richard. 1990. “Official Languages and Language Planning.” In Perspectives on Official English: The Campaign for English as the Official Language of the USA, edited by Karen Adams and Daniel Brink. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Sánchez Pérez, Aquilino. 1992. Historia de la Enseñanza del Español como Lengua Extranjera. Madrid: Sociedad General Española de Librería.

Simon, Paul. 1980. The Tongue-Tied American: Confronting the Foreign Language Crisis. New York: Continuum International.

Skinner, Burrhus F. 1957. Verbal Behavior. Acton, MA: Copley.

Spell, Jefferson R. 1927. “Spanish Teaching in the United States.” Hispania 10, no. 3: 141–59.

VanPatten, Bill. 2015. “Hispania White Paper: Where Are the Experts?” Hispania 98, no. 1: 2–13.

Walsh, Donald D. 1947. “A Survey of the Teaching of Spanish in the Independent Schools of New England.” Hispania 30, no. 1: 270–71.