TIMELINES

EVENTS AND MOVEMENTS

HELLENIZATION

Hellenization in General (Fourth Century B.c.—Sixth Century A.D.)

Hellenization was the spread of the Greek language, values, and culture throughout the Mediterranean world. It was disseminated through the development of local Greek city-states, governmental influence, laws, troops, religion, philosophy, drama, and customs. It developed from the 330s B.C. onwards after Alexander the Great conquered the Near East. In its broadest sense, Hellenization includes the pervasive influence of both Greek and later Roman culture.

Enforced Hellenization (167—164 B.C.)

Antiochus Epiphanes’ policy of enforced Hellenization outlawed the practice of Judaism. This resulted in persecutions of observant Jews, desecration of the Temple, and the destruction of Jewish sacred texts. The Maccabees led a revolt. They succeeded in capturing Jerusalem, and the Temple was rededicated in 164 B.C. This is commemorated in the festival of Hanukkah.

Factions Within Judaism As a Result of Hellenization (After 164 B.C.)

After the persecutions of Antiochus Epiphanes, various groups or “parties” arose within Judaism. These represented different ways of being Jewish in light of Hellenistic pressures. These included:

Sadducees, who controlled the Temple and commerce, emphasized accommodation with the Greeks and Romans.

Pharisees taught Torah and focused on education as a strategy for defending the Jewish community against assimilation.

Dead Sea Scroll community (Essenes). Led by a Teacher of Righteousness, this group preferred separation to avoid contamination with foreign influences. This movement may have originated in the post-164 period or somewhat later, during the reign of Queen Salome Alexandra, 76—67 B.C. The scrolls themselves date from the first century B.C. through to A.D. 68 when Qumran, the headquarters of this movement, was destroyed. Most scholars identify the Dead Sea Scroll community with the Essenes.

Zealots, who advocated active resistance or fighting the occupying forces, originated later than the other groups, in A.D. 6.

The Sadducees, Zealots, and members of the Dead Sea Scroll movement did not, for the most part, survive the first Jewish War against Rome (A.D. 66—70). Only the Pharisees survived the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple. They became the leaders in reconstructing Judaism after 70.

The Greeks and the Romans (After 63 B.C.)

Rome conquered the Greek Empire including the Near East. The common language remained Greek. In time, the Greek deities were simply given Roman names. The process of Hellenization continued through the city-states, schools, laws, religion, and, especially, through the proliferation of mystery religions. These included the Egyptian cult of Isis, the Greek cult of Dionysus, the Persian religion of Mithras, and many others.

JESUS AND HIS TIMES

Herod the Great (Died 4 B.C.)

The Jewish ruler just prior to the time of Jesus, Herod the Great, had engaged in massive building projects including expansion of the platform of Temple Mount and the rebuilding of the Temple. He also constructed Masada, Herodion, the port city of Caesarea Maritima, and many other sites. He built up Jerusalem as a showcase city for the Roman Empire.

Jesus (5/6 B.C. - A.D. 30)

Jesus was born sometime before 4 B.C. since Herod the Great died in that year. Hence his birth is usually dated to 6 or 5 B.C.

According to the gospels, Jesus was born in Bethlehem (a few miles south of Jerusalem) but grew up in Nazareth (in the Galilee in the north). John the Baptist was Jesus’ cousin. John preached and baptized sometime during the mid to late 20s A.D. Jesus had four brothers and at least two sisters.

Jesus’ ministry occurred during the late 20s A.D., approximately 27—30. According to the Gospel of Matthew, he promised his hearers that the Kingdom of God was about to be manifest on earth and he challenged them to live a life of higher righteousness (strict Torah observance). He was put to death by the Romans around A.D. 30. (Some say A.D. 33 or several years later.)

EARLY CHRISTIANITY

Jesus Movement (Ebionites)

Jesus’ earliest followers, the Jesus Movement, were led by James, Jesus’ brother, in Jerusalem from the 30s to the early 60s. They were Torah-observant. They looked on Jesus as human, and expected him to return soon to help establish the promised Kingdom of God on earth. James, Peter, and John were known as the Pillars. Josephus, the Jewish historian who lived from A.D. 37 to about 100, noted that James was killed in 62.

During the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66—70), this movement may have fled to Pella in what is today northern Jordan, returning after hostilities ceased. James’s successor as bishop of Jerusalem was Simeon, another relative of Jesus. Simeon was killed in the early second century.

This expression of the Christian movement continued to exist, but it became increasingly marginalized. They were later referred to as Ebionites or Nazarenes and were shunned by what became mainstream Christianity, Proto-Orthodoxy, as scholars refer to the group that succeeded.

Christ Movement (Proto-Orthodoxy)

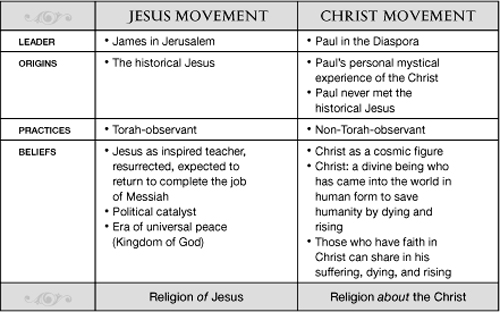

The Christ Movement was led by Paul, in the Diaspora. Paul rejected Torah observance and focused his message on the death and resurrection of Christ. Paul never met the Jesus of history, rarely quoted him, and distanced his movement from that of James’s. In origins, teachings, and practices, the Christ Movement differed significantly from the Jesus Movement.

Paul wrote letters to fledgling congregations during the 50s and early 60s. These were located in modern-day Turkey, Greece, and Italy. His letters are the earliest Christian writings we have, predating any of the gospels.

Paul and Peter were killed in Rome in the early to mid 60s.

The Christ Movement succeeded, bringing in many converts from a non-Jewish (Gentile) background. As this segment of early Christianity grew in the second through fourth centuries, scholars refer to this movement as Proto-Orthodox Christianity. They were the faction favored by fourth-century Roman emperors and thus became the dominant group. Modern Christianity stems from the Christ Movement/Proto-Orthodoxy.

Gnostic Movement

This form of early Christianity originated sometime during the first century A.D.—we don’t know when or how. We know about it not only from the writings of its opponents, but also from the discovery in 1948 of the Nag Hammadi Gnostic writings.

Important writings include the Apocryphon of John, the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Philip, and many others. Unlike the Jesus Movement, which emphasized Torah (law), or the Christ Movement, which focused on faith, the Gnostic Movement stressed gnosis (“insight” or “knowledge”). None of the Gnostic writings was included in the New Testament. This form of early Christianity at times rivaled Proto-Orthodoxy. It declined or was suppressed during the fourth century as Proto-Orthodoxy became the favored religion of the Roman Empire.

FIRST JEWISH REVOLT AGAINST ROME (A.D. 66-70)

Qumran, the headquarters of the Dead Sea Scroll movement on the northeastern shore of the Dead Sea, was destroyed by the Romans in 68. Jerusalem was decimated in 70, along with the Temple. Only the Pharisees survived. For the most part, the Sadducees, Dead Sea Scroll community members, and Zealots did not. Masada, the Zealot fortress by the shores of the Dead Sea, was destroyed in 73 or 74. Josephus wrote about this revolt based, in part, on his own eyewitness accounts.

LATER EVENTS

In 313, the Roman emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, which extended toleration to all religions, Christianity included. In 380, Emperor Theodosius declared one form of Christianity—what scholars call Proto-Orthodoxy—the official state religion of the Roman Empire.

In 325, the Proto-Orthodox bishops at the Council of Nicea developed the Nicene Creed as the authoritative expression of the correct faith. In 367, Archbishop Athanasius of Alexandria, Egypt, circulated a letter outlining the twenty-seven books that compose the New Testament.

MOVEMENTS WITHIN EARLY CHRISTIANITY

COMPARISONS: JESUS MOVEMENT VERSUS

CHRIST MOVEMENT

The Christ Movement differs in origins, practices and beliefs from the Jesus Movement.

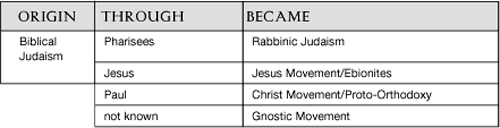

COMPARATIVE ORIGINS

Two movements had their origin in biblical Judaism:

Rabbinic Judaism

the Jesus Movement (Ebionites)

Two movements had separate origins:

the Christ Movement (Proto-Orthodoxy)

the Gnostic Movement

The Christ Movement originated with Paul’s teachings. The origins of the Gnostic Movement are unknown.

CHRISTIAN WRITINGS (IN HISTORICAL SEQUENCE)

There is controversy about the precise dating of some of these writings. In general, for biblical works, I follow the dating suggested by Bart Ehrman in several writings (The New Testament, Lost Christianities, Lost Scriptures) and Burton Mack (Who Wrote the New Testament?).

FIRST CENTURY A.D.

| 50s | Paul’s Letters (Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon) |

| 70s | Gospel of Mark |

| 80s | Gospel of Matthew |

| 90s | Gospel of John |

Sometime midfirst century

Q—the common source used by Matthew and Luke that does not come from Mark

Sometime late first century

Didache

Letter of James

Parts of the Gospel of Thomas

Letters attributed to Paul but probably not written by him (e.g., 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians)

Gospel of Luke, Book of Acts (dates range from the 90s to the 120s)

SECOND CENTURY

| 100 | Epistle of Barnabas (late first century or early second century) |

| 110s | Ignatius of Antioch’s letters |

| 130s | Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho |

| 140s | Marcion’s Antitheses |

| 150s | Infancy Gospel of James |

| after | 150 |

| Apostles’ Creed | |

| Epistle to Diognetus | |

| Gospel of Peter |

THIRD CENTURY

Tertullian, Against Marcion (early third century)

Recognitions of Clement (sometime during the third century)

The Homilies of Clement (sometime during the third century)

FOURTH CENTURY

Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History (early fourth century)

367—Athanasius’s Thirty-ninth Festal Letter—lists the twenty-seven books of the New Testament