LESSONS FROM THE MASTERS: HOMAGE AND REINVENTION

Art is built upon other art. For centuries, artists and architects have learned from and celebrated the work of their antecedents and their peers. Drawing is the very means of this research. Michelangelo, born some fifty years after Masaccio’s death, made studies from his frescoes. Rubens drew from all the Renaissance masters, as his student van Dyke drew from him. The only record we have of Leonardo’s destroyed Battle of Anghiari is Ruben’s pen-and-chalk study of it. Rubens drew from Raphael, and earlier, Raphael, in his fresco depicting the School of Athens, paid tribute to his revered senior colleagues Michelangelo and Leonardo, dramatically por- traying them in this composition.1

The list of architects who participated in the design of Saint Peter’s in Rome (1506–1625) is a roll call from the high Renaissance. The visions of Bramante, Raphael, and Peruzzi, among others, were crowned by a dome Michelangelo had designed, which was inspired by Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence.2 Gaudí’s consummate masterpiece, the Sagrada Família in Barcelona (begun in 1882 and still not complete), was a work already two years under construction when Gaudí was brought in to collaborate with Francisco de Paula del Villar. Villar resigned and Gaudí continued on for the rest of his life.3

Mary Cassatt was enraged by the rejection of her painting Little Girl in a Blue Armchair from the American section of the 1878 Paris Exposition Universelle. She was particularly piqued since her close friend and much-admired colleague Edgar Degas had “even worked on the background.”4 She perceived the rejection as an affront to the both of them. Picasso famously borrowed from everyone. His folio of lithographs drawn from Velásquez’s Las Meninas is but one instance of his appetite for the work of others.

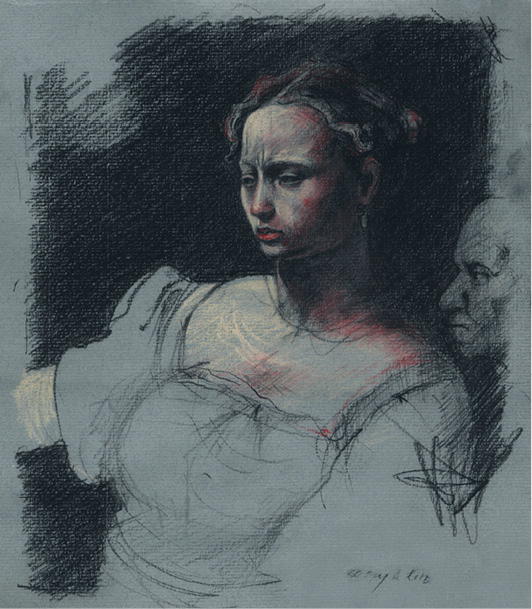

FIGURE 1

Study after Caravaggio. Judith Beheading Holofernes, c. 1598.

The following exercises invite students to look back to the works of the past to inform their developing understanding of drawing. The master studies should not be considered attempts at forgery but a means of investigation. To a greater or lesser degree, the students reinvent the work and make it their own.

ASSIGNMENT

Select images from a master in which the work of the hand is clearly visible. Avoid reproductions with many blurred or indistinct passages. Repeatedly practice details of the drawing that exemplify the original artist’s handwriting before attempting to reproduce the entire drawing. This “fool around” page made of bits and pieces of drawing should also be an investigation of the design of the page with concern for negative space and passageway through the page. (As the fragments of drawing accumulate, arrange them in a way that gives the page a major gesture or spine.)

FIGURE 2

Study after Leonardo da Vinci. Title unknown, 1510–13.

Make an underdrawing of the drawing in the spirit of the rapid figure sequences practiced previously. Allot no more than 2 to 5 minutes for this (see “Monkeys,” pp. 43–50).

Make a separate rapid underdrawing, this time as the underpinning for a longer study of 20 to 30 minutes. Follow the master’s hand respectfully but at the same time freely and with speed—not line for line.

Redraw the previous image at a larger scale, up to twice its original size. After this, make another enlargement, this time more interpretively. A change in drawing medium is usually helpful. Any medium on any paper. 30 to 45 minutes.

In an additional final drawing, “collaborate” with the chosen artist but reinvent the masterwork. In this drawing a further change in medium and scale is strongly recommended. Any medium on any paper. 1 hour or longer.

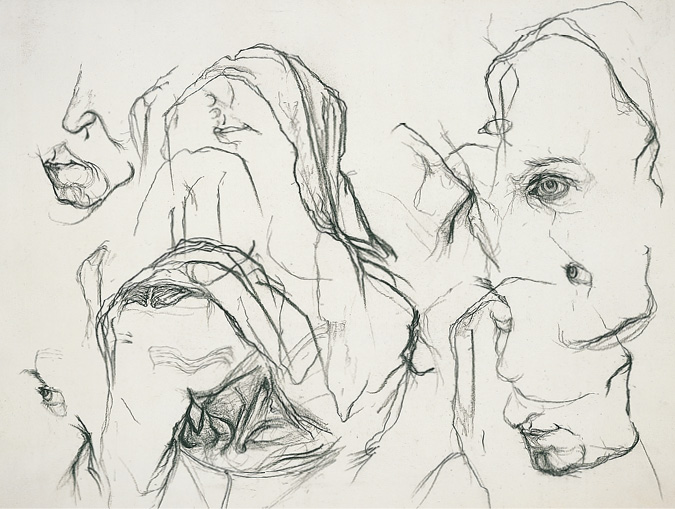

FIGURE 3

Derived from Albrecht Dürer’s Portrait of Dürer’s Mother, the study provides a classic example of a response to the first exercise in this series. The lines weave together the profiles, the jaw line, the carefully studied eyes, and an aging neck, combining these elements to create an intriguing ambiguity of positive and negative intervals and volumes.

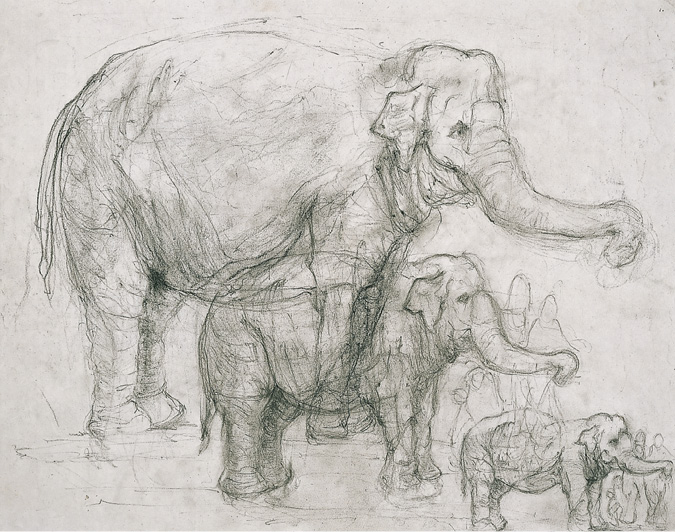

FIGURE 4

The study of Rembrandt’s Elephant gives the enlargement portion of the assignment an original twist. In the design of the page, the two larger elephants are superimposed in a transparent fashion, one above the other. The two larger studies seem to levitate above the firmly positioned smallest elephant, with its feet planted securely at the bottom edge of the paper.

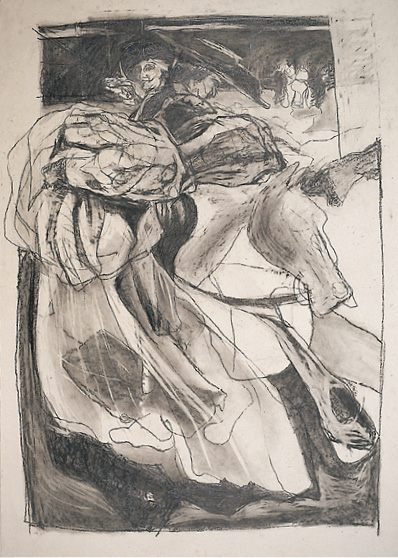

FIGURE 5

The drawing presents a freely executed collaboration with Manet’s Mlle. V en costume d’Espada. A number of spatial liberties have been taken. In a cunning reworking, the figures of the foreground toreador and the picador in the middle ground (in profile) are conflated. Their shared body conjoins opposing postures, achieving a balletic spin around a central axis. The arc described by the toreador’s hands is greatly expanded, enhancing the balletic movement. A transparently rendered cape reveals the toreador’s enlarged left hand and forearm, which press toward the viewer as if breaking through the picture plane. The swirl of the cape, with its incised and erased marks, elevates the drama of movement. The two dark hats meld with the rectangular shape of the stands to frame the two faces; the three-quarter face looks back at us with a confident gaze.

FIGURE 6

In examining Raphael’s Study for the Phrygian Sibyl, the author makes multiple attempts to conquer aspects of the head and arms. Notice that in each of the series, no two attempts are identical—each is drawn freely to gain understanding of aspects such as the twist of the neck, the set of the eyeball in the depth of its socket, the complexity of the elbow’s articulation, the pressure of the arm on the heel of the hand, the grasp of the fingers on the ledge.

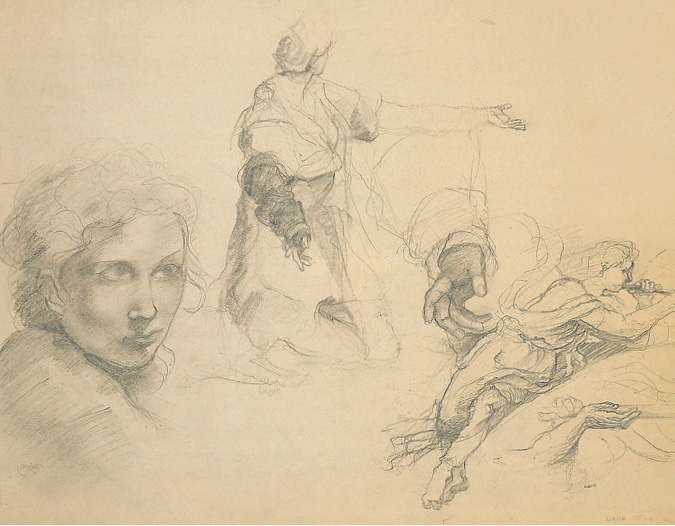

FIGURE 7

The drawing presents several studies from Andrea del Sarto, creating from them a composite arc. This arc is enhanced by the layered dark tones employed to bring portions of each figure to a higher degree of finish. Of particular interest is the evolution from the transparent light marks of underdrawing to the build up of darker hatching, together with incised contour lines that more fully realize the body’s volumes and features and explain the drapery of fabric.