The dumb-object drawing exercise opened my eyes to simple observation, which has been helpful to me in my architectural work ever since. Careful examination of the forms and spaces, shaped by time, use, and natural forces often reveals something much richer than anything I could have constructed just by thinking.

On the street I picked up a rusty piece of metal that had long ago lost its utilitarian value and purpose. Drawing it at full scale or even larger forced me to observe every aspect of it and invent ways of drawing the intricate differences in materiality, structure, and shape. Having only this one little subject for constructing a large drawing made it impossible to avoid the relationship between the object and space, the portion of the paper left blank, and how light fell on it and made this seemingly flat and insignificant object into a rich, surprising form. — ANNE ROMME

The “dumb object” falls beneath conventional aesthetic radar. Often intimate to in- significant in scale, it is not valued as subject matter worth commemorating in drawing. In the 1960s and 1970s, artists Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine brought the dumb object to prominence with their renditions of clothespins, lipsticks, screwdrivers, bathrobes, and other such objects. They were not the first to do this. John Peto and William Harnett, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque all relished the ordinary and overlooked. In 1817 William Hazlitt wrote that Rembrandt “took any object, he cared not what, however mean soever [sic] in form, colour, and expression, and from the light and shade which he threw upon it, it came out gorgeous from his hands.”1

FIGURE 1

Drawing from the dumb object is introduced at the same time as the handwriting and master-studies assignments (see pp. 40–42 and the preceding pages). It is an adjunct and not a separate assignment in itself. The dumb object is drawn intermittently through the balance of the program. Tracking the same, self-chosen item as the year unfolds aids the student in layering new concepts and skills. Its utility is in how it widens the eye, causing it to stare at the world and always to look for the visual surprise.

ASSIGNMENT

Choose as your object something you would previously never have thought of drawing. Let the drawing be influenced by the concepts that you are working with at the time. Draw this object with any medium at any size in any manner and scale and for any period of time.

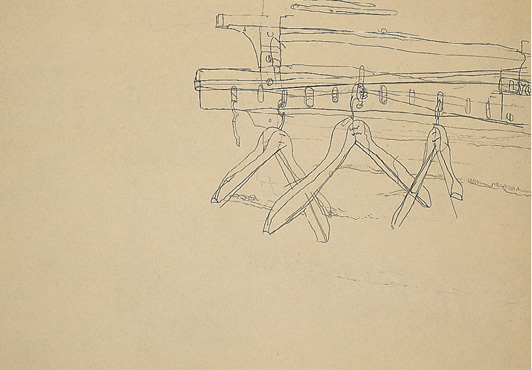

FIGURE 2

At first glance this blind-contour drawing seems to be a breezy offhand study of an ordinary circumstance: three hangers suspended from a utilitarian rack. However, the careful eye and hand of the artist has here commented on significant details and points of joining. The zigzag rivets that marry their two halves together show that the hangers are of wood. The rack appears to be metal because the slender depth of its members contrasts with the hangers’ more substantially thick shoulders, and the bolts and joining details present further evidence. The sophisticated occupation of the upper right portion of the page suggests a likely corner location in a room or closet. Each hanger is suspended at a different angle, yet optically they cross each other in the drawing, sharing an animated gesture.

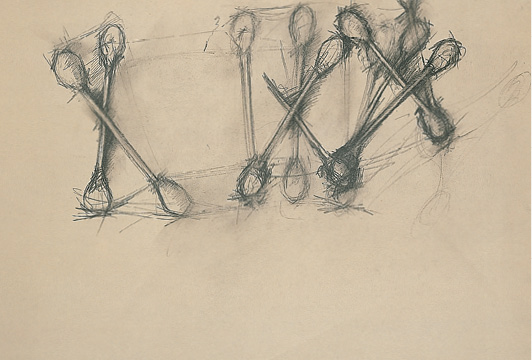

Figures 3 and 4 echo the Figure in Motion exercise (see pp. 30–34) in which each posture the model takes changes somewhat from the previous one.

FIGURE 3

Several Q-tips were placed and drawn, then one or two were repositioned and drawn again. Light markings that chart the negative space seem to measure and guide the tips’ next positions and provide an underlying structure to the plot. The emphatic charcoal markings on some of the tips and sticks contrast with lighter, almost negligent markings on others, alluding to an object momentarily at rest and then in motion. The overhead—or plan—perspective creates the illusion that the Q-tips are laid on the very page the viewer is observing.

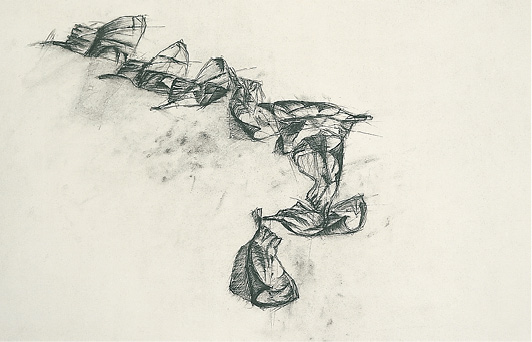

FIGURE 4

By contrast, the continuous hooked-curve, conga line-like placement and the incrementally changing scale of the pencil shavings create an illusion of depth. The detritus of charcoal bits and powder provides another level of visual wit. Tone, employed to indicate shadow on these tiny objects, connects the fragments, enhancing a curving spinelike gesture.

The drawings in figures 5 and 6 study ropes, each with a different strategy.

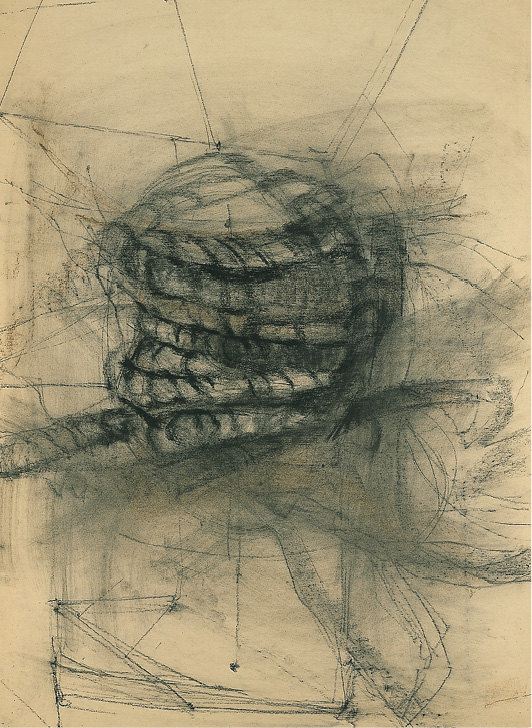

FIGURE 5

A centrally positioned coil with lines of rope escapes to the right, left, and bottom of the page. The coil was worked and reworked to a velvety darkness, with glints of light catching the twist in a whirling motion. The peripheral chords twirl away from this implicit spin.

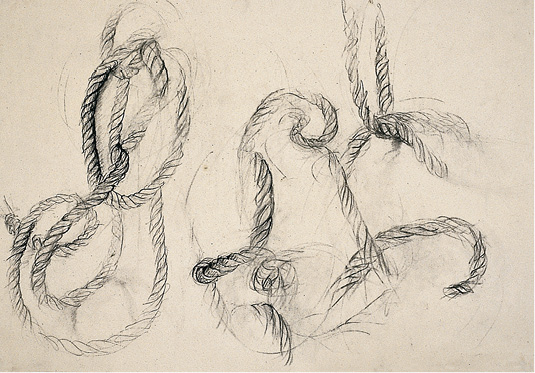

FIGURE 6

A length or two of rope is looped about as if being knotted or tangled. The employment of both hard and soft focus imparts a depth of field to the work: the darker, more-detailed areas come forward as the lighter, less-detailed areas recede. This lends an undulating motion to the ropes that a breeze might generate—rather than the sprung energy of a coil.