FIGURE 1

SHOESCAPES

Having drawn since I was a child, I thought I was pretty good until I took Sue Gussow’s drawing class during my first year. In one of her exercises—drawing shoes piled up on top of each other—I learned how to observe. The nature of the object made you look at both the interior and the exterior of the shoe. The complexity of the total shape forced you to look at the negative space in and around the assembly. There were folds in the leather to consider, how the foot shaped the shoe by walking in it. This was a very elegant problem that made you really look. Drawing this everyday object gave me the ability to draw complex assemblages of objects, to consider space inside and out. My mother, who is a painter and teacher, loved this exercise and some others taught in Sue Gussow’s class so much she taught them in her own drawing course. — JEE WON KIM

Akin to architecture, clothing provides shelter and enhances or announces culture, function, taste, and class. It could be argued that the shoe, beyond all other clothing, is the most architectonic in its structure and function. Standing atop a footing—the sole—built in adherence to a volumetric model—called the “last”—the shoe provides the foot, its occupant, with protection from climate and injury. An architect might well be intrigued by the construction—the anatomy—of the modern shoe. The shoe as we know it is a complex structure, and like the house it has acquired a special vocabulary to identify its structural members. Some of its elements are generally familiar: sole and heel, tongue and lacing. But most terms are not common to their wearers: the outer, the puff, the shank, the toe cap, the quarter, the vamp. It is, however, mainly the shape of the shoe, the void it encloses and the plane it stands on, that is the principal preoccupation of the Shoescapes assignments. Shoes present an excellent adjunct assignment to drawing from the human form; their convexities and concavities are modeled upon the foot itself.

In order to avoid a preoccupation with the shoe’s surface attributes—the stitching, the lacing, the grommets—and to focus on the shoe’s occupation of space, shoes will be examined not singly nor in pairs but in multiples—five or six shoes. In studying the group simultaneously, the primary concern will be devoted to the manner in which the shoes are placed to choreograph a space.

In addition to their allusion to function and fashion, male, female, or unisex, shoes come with yet another narrative attribute: they indicate direction. Even when independent of the foot and placed immobile on the floor, the shoe is a visual vector in the space: each toecap points to a specific direction. This guides the observer’s eye across the field of paper on which the shoes are drawn.

ASSIGNMENT

Choose five or six shoes. Do not select brand-new ones; find shoes that show the imprint of a foot, the embossment of toes, wrinkles from wear. The foot’s impression indicates dimensions of time and memory. The number of shoes in the assignment requires that you deal with a complex arrangement of several objects assembled in one space: consider movement and passageway across the field of the paper.

Toss several shoes randomly or manipulate them to form an interesting arrangement. Remember that it is one thing to create an exciting arrangement of actual shoes and quite another for this arrangement to become a good design on paper. Consider how the entire group will fit on the page. Read the group of several shoes as one creature with an implicit (invisible) connecting spine.

Draw four quick studies of all the shoes, drawing them together at once. Remember the implicit spine. Consider how the total configuration of shoes might best be placed on the paper—high, low, center. Hold back from focusing on details. Use the lines that best describe volume and plane. In each of the four drawings change either the shoes’ arrangement or your own vantage point. Vine charcoal. 18" x 24" (or larger) newsprint. 15 minutes each, no longer.

Negative Space/Blind Contour. From the four studies choose the best composition. Draw the negative space surrounding the entire group of shoes. Look for narrow shapes of negative space that intervene between shoes placed at a small distance from one another. Think from the contour edge outward rather than focusing on the form of the shoe contained within the contour outline. Some light marks can be made, minimally indicating interior shapes, to test out the accuracy of the external contour, but keep the focus of the drawing on the exterior negative space. Use any drawing medium. 18" x 24" (or larger) white paper. 1 hour.

Freestyle Drawing. From the same composition chosen for the negative-space drawing, do a freestyle drawing but incorporate the following suggestions: employ areas of tone to address the issue of passageway, hatching in connecting shapes of tone to carry the eye from shoe to shadow to shoe. Shapes of tone may be employed to allude to the local color of a shoe—the level of gray that shoe might appear to be in a black-and-white photo. Local color can always be altered—or ignored—if that enhances the design of the drawing. Keep away from explicit detail until the later stages of the drawing. Detail is almost always the last strategy. Any drawing medium on any paper 18" x 24" (or larger). 1 hour.

The drawings in figures 2 and 3, both by the same hand, are clear examples of progress from a rapid study to a more fully realized drawing with a consciously chosen design strategy.

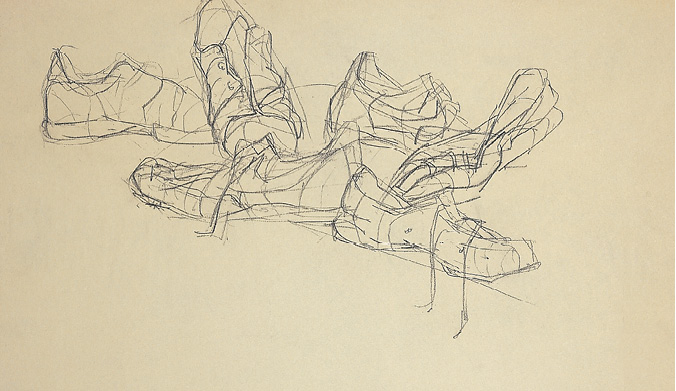

FIGURE 2

Thought is given to the gestalt and the placement on the page of the six randomly tossed shoes. They occupy only the top portion of the paper and march from top left downward to the white ground below. (Consider the paper with the bottom horizontal portion eliminated. The descending movement would be considerably diminished.) The two shoes with toe caps facing left counter and secure the compositional descent of the group of shoes to the paper. Planar slicing was employed to analyze the three-dimensional carving of the shoes; even their laces were drawn in planar fashion.

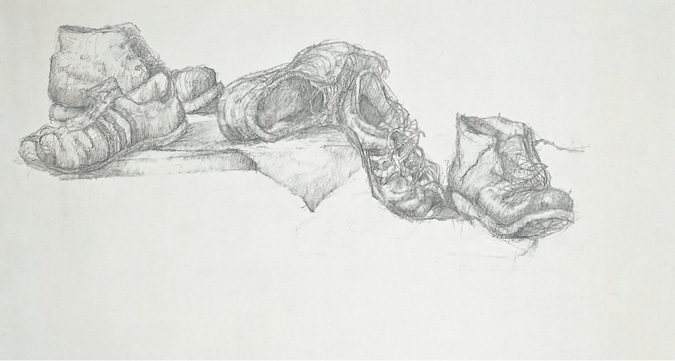

FIGURE 3

The drawing employs tone to indicate local color (the stripes on the running shoes), to model the form of the shoes, and to allude to cast shadows. Here the shoes are placed more consciously. Only one leftward-pointing shoe opposes the downward motion. (Notice one shoe from the previous study has been removed.) The increased buffer of white paper space enhances the drama of the group’s movement. Apparent heel-to-toe connections create a “spine” that further enhances the shoes’ shared thrust. The interior and exterior of the shoes are more fully explored here, as is the clear delineation of the top ledge of the wall of leather making up the shoes’ openings—the housing of the foot.

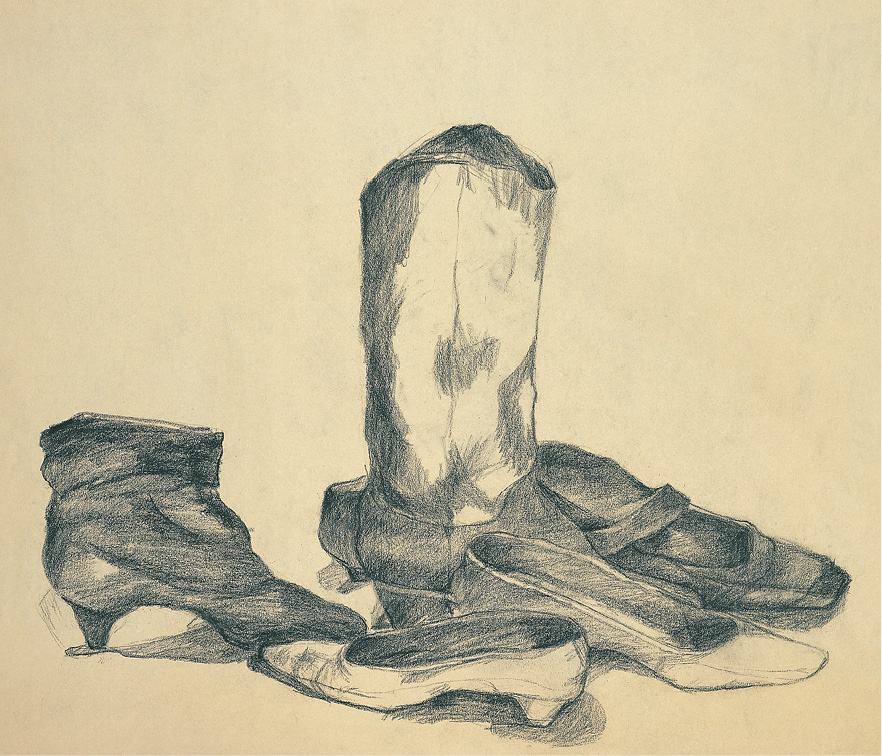

FIGURE 4

The concept of this drawing is especially architectonic. The top of a centrally placed boot rises like a tower in the center of several low-heeled pumps, echoed by an auxiliary structure—a lower black boot at its rear. All are lined up in parallel profile with tension created by the backward-facing white pump. The fairly abrupt cessation of modeling in the white pump and in the tower of the tall central boot links them to the flatness of the white paper. This creates a spatial ambiguity between the drawing’s illusion of volume and the flatness of the picture plane.

Figures 5 and 6 play with shoelaces as lines that extend the action of the shoes. In figure 5 the laces of two shoes tie the composition together in a tug-of-war. The laces in figure 6 lay casually away from the left-hand block the three pairs of shoes occupy. In the context of their design each drawing employs the shoelace to enhance a psychological statement. In drawing and design there is often the epiphany of unexpected meaning. This is another aspect of visual surprise.

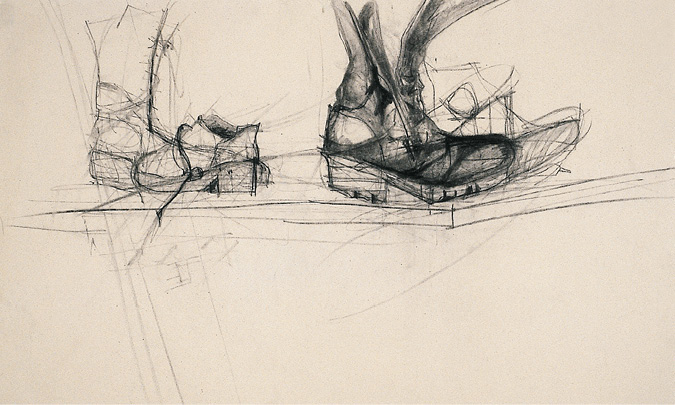

FIGURE 5

It is the shoes themselves that march forward in lockstep, their up-turned toes adding animation to contradict the more static appearance of their profile “elevation.” The tug from the left-facing shoe creates the warring tension, keeping the black boot’s forward march anchored on the page. A playful tension between the paper’s two-dimensionality and the drawing’s three-dimensional illusion is created as the top edge of the page and eye level share the same line.

FIGURE 6

The placement of the shoes and the rendering of their wrinkles makes the viewer aware of their missing occupants held together in a close conversational square. The flowing laces echo what might be an unseen gesture of arms. The grouping at the page’s upper left emphasizes the close proximity of the “occupants.”