The challenge of drawing my feet became evident the third week of the assignment. How does one draw one’s own feet week after week, I wondered. I learned to carefully look and to accurately see what was before me. I found that gravity plays an important role in how the masses of the feet relate to their context. I realized that the tendons, ligaments, connective tissues, digits of varying sizes, and bones all reveal themselves differently through the skin when oriented in different positions. Certain parts of the feet, ankles, and lower legs appear soft and rounded when restfully reclining on an ottoman, while the same anatomical elements are quite angular and planar when standing firmly in front of a mirror.

— CHARLES KREKELBERG

FIGURE 1

Feet are that portion of our extremities most distant from the eyes. Feet most often fall beneath our gaze. Save for the daily ritual of housing them in shoes (further obscuring them from view), we seldom take a serious look at them. Unlike our hands, with which our eyes are in constant collaboration, our humble feet are more typically called to visual attention when they cause us pain (fashion slaves excepted). When, for instance, was the last time you carefully examined the sole of your foot? Yet there they are—those feet—our base, our daily contact with the ground plane, with the earth.

When we speak of a firm footing, we refer to a stability of posture or a secure basis. In architecture the form called “footing” mitigates between foundation walls, interior columns (in larger structures), and the earth. Usually rectangular in form, typically composed of concrete, and larger than load-bearing columns, footings are thrust deep into the earth to establish a building’s stance and stability.

The Feet and Legs drawing project evolved from the Shoescapes assignment. Although shoes had been discussed as structural housing for feet, many of the drawings pinned up for critique appeared to be studies done from new shoes. Their more prominent attributes were stitching, laces, grommets, straps; no foot seemed ever to have occupied them.

The in-class exercise required students to remove their shoes and take a good look (while drawing) at their feet—their feet undressed, their feet in socks, and finally their feet back in shoes. The resulting drawings, however well drawn, resembled amputations. Feet were abruptly terminated at the ankles or legs were severed arbitrarily at the calf or somewhere below the knees—inventory from a body-parts shop floating about on a field of white paper.

The project evolved further. Drawing longer portions of the leg entering the page from the top, side, or bottom of the paper’s edge immediately interrupts and divides the field of the page, creating that intriguing dialogue between negative cutouts and positive rendered volumes. Studies of feet and legs taken from their mirror image did not present as challenging a perspective as actual feet and legs drawn by gazing downward or outward, where the unexpected shapes created by foreshortening come into play. One student presented drawings depicting her actual legs extended to a mirror so that one foot toed its reflection, creating a four-legged image and opening a virtual window to the space beyond the picture plane. The scheme was incorporated into further assignments.

ASSIGNMENTS

WEEK I

Draw three drawings of your own feet and legs, either mirror image or viewing actual limbs, each in a different posture: first posture, legs and feet unclothed and unshod; second, legs with feet in socks; third, legs with feet in shoes (and socks—or not). Legs should be drawn from somewhere above the knee and should enter the drawing from the edge of the paper. Use vine charcoal. 18" x 24" (or larger) newsprint. 20 to 30 minutes for each posture.

Consider the three previous drawings and choose the most interesting posture as a scheme for the final drawing. It will be useful to make marks on the floor (or chair, etc.) to indicate the position of your feet and legs. Bits of masking tape are good for this purpose. Begin the drawing with feet and legs naked. Use any easy-to-erase medium on a sturdy 18" x 24" (or larger) sheet of paper. About 30 minutes.

Put socks on your feet and then continue to work on the same drawing, resuming the same posture. (This is the reason that marking the placement of feet is necessary). After another 20 to 30 minutes, put on shoes and continue on the same page. At each stage, erase only when the drawing becomes confusing. With each new layer, erasure may be necessary to clarify the drawing, but keep erasure to a minimum so that the transparency of the drawn shoes and the presence of feet are in evidence.

WEEK II

Draw from your actual feet and legs, not from a mirror image. This vantage point introduces the challenge of foreshortening (looking either downward or outward) in the various postures drawn. The goal of foreshortening is to create the illusion of projection forward. It is complex to carry out given the endless variations of posture the body might assume. It is achieved by an apparent compression of those volumes that recede from the observer’s eye. Key to the process is the keen observation of unexpected shapes—both positive and negative—that the eye will encounter. Charcoal or other mutable medium. 18" x 24" (or larger, although larger is encouraged) newsprint. Three studies, 30 minutes each.

Select the best of these three pages as a starting point for a freestyle study. Any drawing medium on any paper 18" x 24" (or larger). 1 hour or longer.

WEEK III

Draw your actual limbs as you have done the previous week but also include their mirror image in the drawing. Be inventive with your three poses—i.e., one foot might engage the mirror image—and with how you position the mirror. Vine charcoal or any mutable medium on any paper 24" x 36" (or larger). Three drawings, 30 minutes each.

As during the second week, select the best of the three previous studies for a freestyle study. Any drawing medium. Sturdy paper, 24" x 36" (or larger). 1 hour (or longer).

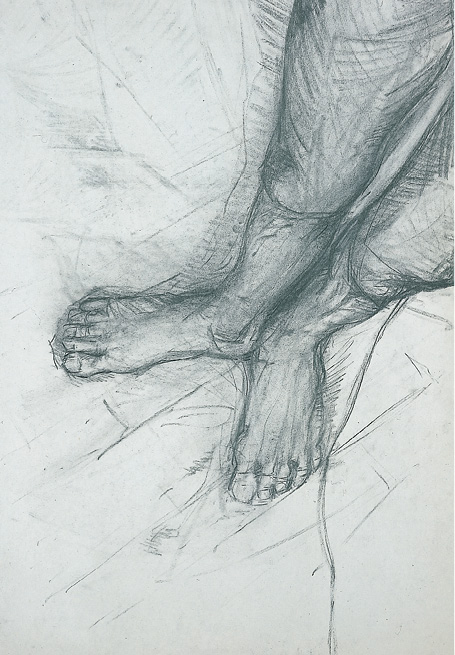

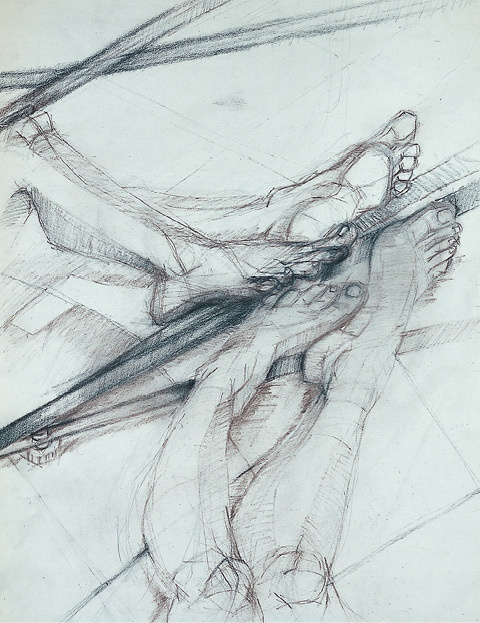

The drawings in figures 2 and 3 respond to the first and last segments of the first week’s Feet and Legs assignment. In a search for the complex shifts of form in the foot’s shaping, the drawings present a loose-handed version of planar slices.

FIGURE 2

The drawing employs planes in carving the foot’s reciprocal convexities and concavities.

FIGURE 3

The drawing reveals a layering, first of socks, then shoes. Through the layers of cloth and leather, transparency allows the viewer to glimpse the shoes’ occupants. Both drawings describe the student’s own legs and their reflected images. Note the contrast in the thickness of the limbs as the tilt of the mirror thins out the legs’ dimensions. Notice as well the radial position of the feet as they fan out from the student’s perspective—her line of vision penetrating the almost-touching pair of heels at the left.

FIGURE 4

The drawing shows a straightforward mirror image of the student’s fully dressed feet. Socks, wrapped about the ankles, echo the curved handwriting that describes the volumes of calves and knees. The assured rough charcoal marking describing the laces, wrinkles, and shoes speaks boldly of the feet inside.

FIGURE 5

Downward perspective dominates as the legs enter the page from the upper right corner. The foreshortened lower limbs enhance the sharp downward view. This thrust is anchored by the angled-foot position, which proclaims the floor plane. Turn the drawing upside down (or rotate it sideways with legs at lower right), and the spatial orientation in which it was drawn is apparent. Viewing it as presented is a more powerful design statement. It is useful in design and critique to turn work upside down or sideways to view it anew. Many design epiphanies occur in this way.

FIGURE 6

The mirror image expands the virtual space, opening it to the spatial realm beyond the picture plane. The actual legs, which enter the page from the bottom, come into the viewer’s space in front of the picture plane. There are echoes of Giacometti and planar drawing in portions of the knees and feet—particularly useful in analyzing the underside of the reflected foot. The student wittily extends the toes of the reflected foot past the mirror’s parameter to play with the toes of her actual foot.

FIGURE 7

The drawing weaves all aspects of the problems presented into a nude/sock/foot/shoe theme and variations, also adding issues of transparency and gesture. To the first underlying pose—one leg with a nude foot and the other encased in a knee sock—the student overlays a second shod posture. A light transparent handwriting in crossover places lends the legs a rhythmically kicking and rotating motion that rolls out and upward from the bottom left corner of the page.