In my first drawing class I felt like I was surrounded by experts. It seemed that for some students, it was their second, third, or even fourth time taking drawing. I was convinced that they had been born with the ability to draw. Genetics had given them hands that could create masterpieces. When it came to drawing the model, my hand locked up. The model’s face went from any ordinary face to something contorted, asymmetric, grotesque. Where did Professor Gussow find this guy? How could I compress this face into two dimensions? A half hour went by, and I had a crooked egg with an ear and a lot of erasure marks. As that first semester went on, the model started to look more human to me. By the second semester, he started to look human on my newsprint.

It took almost the two full semesters to realize that my hands were an extension of my eyes. It’s been ten years, and my most difficult class has stuck with me. I draw on business cards at meetings, on receipts during rush hour, on paper tablecloths during meals, and for work everyday. My portraits are small and usually get thrown away or shoved into the glove compartment of my car, but they tie me to the people around me. For a minute or two, here and there, I engage in a quiet relationship with my subject. — ELIZA CHAIKIN

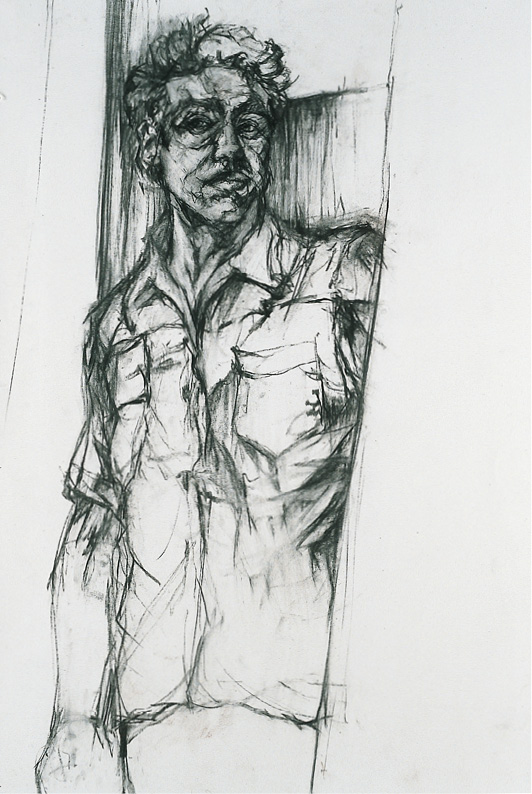

FIGURE 1

Physiognomy, the revelation of human character portrayed by facial features, is a study of endless fascination. In all manner of encounters in daily life, we study one another’s faces to discern meaning. We do this naturally, without undue or even conscious consideration. In many of the arts—literature, theater, painting, drawing—the face and the play of its features is a matter of intense scrutiny. The features and their expressions are tools in an actor’s trade; their configuration, the landscape for a portraitist’s brush or pencil.

Attaining facial verisimilitude is an intense preoccupation for anyone invested in drawing the human form; achieving that likeness is keenly gratifying. Surprisingly, a major portion of the first semester of Freehand Drawing students are advised not to focus on likeness. In the rapid figure exercises (see the “Figure in Motion” studies, pp. 30–34), they are encouraged to ignore features altogether and simply to mark an abbreviated shape indicating the form of the head. (The jawline and the back of the skull might be accounted for, replacing the pervasive generic oval to show the head’s spatial orientation.) Why divert the student’s attention from this particularly compelling aspect of figure study? It is precisely because the desire for likeness is so spellbinding and appealing that once the focus is on the face the remainder of the body—its gesture, volume, occupation of space—will not receive appropriate attention.

Two weeks before Thanksgiving break, drawing from the skull and head exercises are introduced in studio. (At about the same time, students embark on studies from Giacometti, see pp. 66–69). In working from the skull, the focus is not on the skull alone; it is also on the skull in relation to the column of the spine and the spine’s connection to the shoulder girdle (the encircling configuration of collarbones and shoulder blades), and their relationship to and independence from the ribcage. These relationships make up a critical and difficult territory in portraiture. How the head is held aloft is a spatial and structural configuration of particular interest to the student of architecture.

At Thanksgiving students have the occasion to draw family members, and it is important that a concern for structure underpin the desire for likeness.

Skulls and Heads

In no other portion of the body is the underlying bony structure so telling as it is in the head. The shape of the skull, the terrain of the face—made up by the prominence of the cheekbones and bridge of the nose, the depth of the eye sockets, the cut of the jaw—the set of the neck, the tilt of the shoulders, and the configuration of all of these together are as crucial to likeness as is the careful delineation of each facial feature.

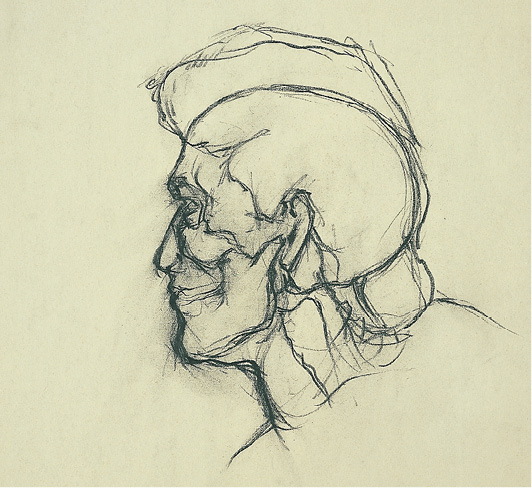

FIGURE 2

There is a clear-cut interposition of the skull and the model’s head. The just-past-profile position of the model’s head helps reveal the prominence of the cheekbone and the globe of the lidded eyeball set in its socket, with the eyebrow describing exactly the angularity of the socket’s top ledge. A contour line indicates the location of the skull beneath the model’s heavy mass of hair and the curve of the neck, allowing a visible forward thrust of the head.

EXERCISES

The Skull and Head exercises follow the pattern of those described in “The Figure and the Skeleton” (see pp. 51–54). Note that it is valuable to do a number of studies of the skull alone, rotating its position every 5 to 10 minutes. Do this exercise before posing the skeleton and model together to avoid focusing attention entirely on the model. Studies of the skull and model’s head interposed are of particular value.

For the next 2½ hours, draw the skeleton positioned together with the two live models, with individual members of the class joining the posing group for 20- to 30-minute intervals. Each successive student takes a different place on the floor than the preceding student occupied. Students do not pose as an aggregate. Nonetheless, the resulting portrait group maintains its own spatial integrity and appears to be a group portrait. Easily mutable medium—charcoal, pastel, soft pencil—on any large horizontal paper 24" x 36" (or larger).

Both the models’ and skeleton’s positions turn and stop at fixed intervals in a rotating arc in figures 3, 4, and 5.

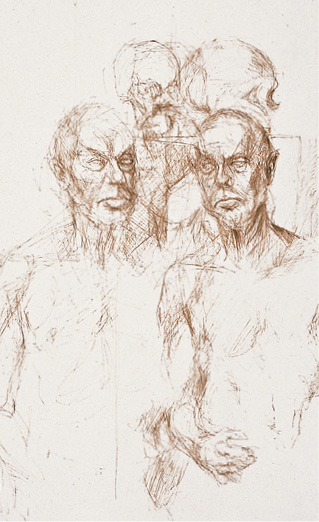

FIGURE 3

Erasures made during the process of the drawing add dimensions of transparency and memory. The skull and model at the right overlap profile and three-quarter views, lending each image a curiously Cubist stamp. Although the head at right does not have a clearly marked underlying skull, its presence is implicit.

FIGURE 4

Two skulls are drawn just behind a double view of a male model. Finely modulated tones of pen and ink depict the three-quarter views, slightly inclined toward each other. While each face indicates its underlying skull, the drawing also presents a sensitive double portrait of the model as a specific human being. The work is enhanced by the gesture of the lightly sketched hand crossing his abdomen.

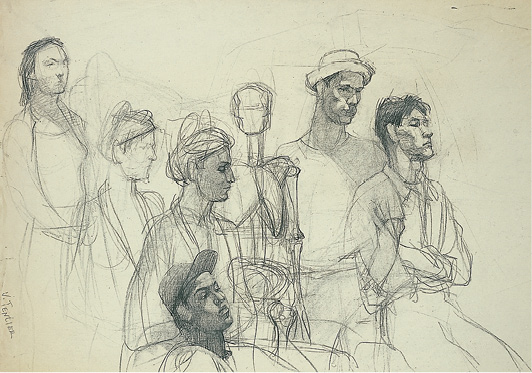

FIGURE 5

Students took turns posing. While minimal attention is given to the bony formations of the skeleton face, the portrayal of each individual classmate sharply reveals these structures. The clearly plotted-out volume of space occupied by each student gives rise to arresting spatial overlaps in the drawing. The arm of the standing figure on the far right shares a contour with the seated figure’s collar, and his elbow penetrates that figure’s chest. Such spatial ambiguities succeed in engaging and amazing the viewer’s eye.

Portraits

Portraits are assigned four times over the course of the two semesters: a self-portrait is the first week’s assignment; drawings of family members are requested during Thanksgiving break; and a self-portrait and a portrait of a classmate are assigned at the end of each semester. The self-portrait from the first week provides a benchmark for evaluation of growth, both artistic and psychological. The final portraits are a culmination and celebration of each individual’s achievement.

ASSIGNMENTS

Family Portraits

Posing. Make sure your sitters are comfortable and engaged in some sedentary activity—watching TV, reading, board games, cards, even sleeping—distracting them from the self-consciousness of being drawn. Include some portion of the body beyond head, neck, and shoulders. Body language and shape are as telling of likeness as facial features are; one recognizes friends, even mere acquaintances, halfway down the street by these characteristics.

Likeness. While it is not possible altogether to dismiss the desire for likeness, avoid, as much as possible, aiming for it. Throughout the drawing process, keep previously acquired drawing concepts—placement on the page, the gesture of the sitter, the angle of the neck, the set of the shoulders, the sculpture of the entire head, the planar landscape of the face in which the features are discovered—foremost in your thoughts. Always seek the skull beneath the skin. Likeness enters through the side door, most often when other aspects of drawing are at the forefront of attention.

Note: Family members and friends are likely to point to discrepancies between their view of themselves and the image you are drawing. Do not feel impelled to please. Never alter your drawing to accommodate your sitter. This is good practice in the long run—and character building. Any medium, paper, and paper size. Any serious amount of time, as this will vary with the patience of your sitter.

Self Portrait and Portrait of a Classmate. Depict at least three quarters of the body in one of the two drawings.

In the self-portrait consider the gestures you make while drawing as an essential element within the work. Use mirrors to activate the space in an unexpected way. When drawing the self-portrait—if it is the three-quarter-body drawing—consider touching the mirror with some portion of your body to open the space of the page outward to the space in front of the picture plane.

In drawing a bust portrait—head, neck, shoulders—locate the head securely on the stem of the neck. Notice the manner in which the neck emerges from the shoulders. The neck is always columnar in form. Do not treat it merely as two lines stuck on under the jaw. In a portrait the set of neck and shoulders is critical to lending gesture to the drawing.

While all features are essential to the facial landscape, eyes are usually the most compelling—engaging the viewer’s own gaze or looking distinctly away from it. This engagement or nonengagement lends a psychological gesture to the work. Remember that the eye is not a flat lozenge or almond-shaped feature ending at the edge of the lids. Always search for the globe of the eye, and draw it in the depth of the socket in which it is set. Any medium. Large paper is recommended. 1 hour at minimum.

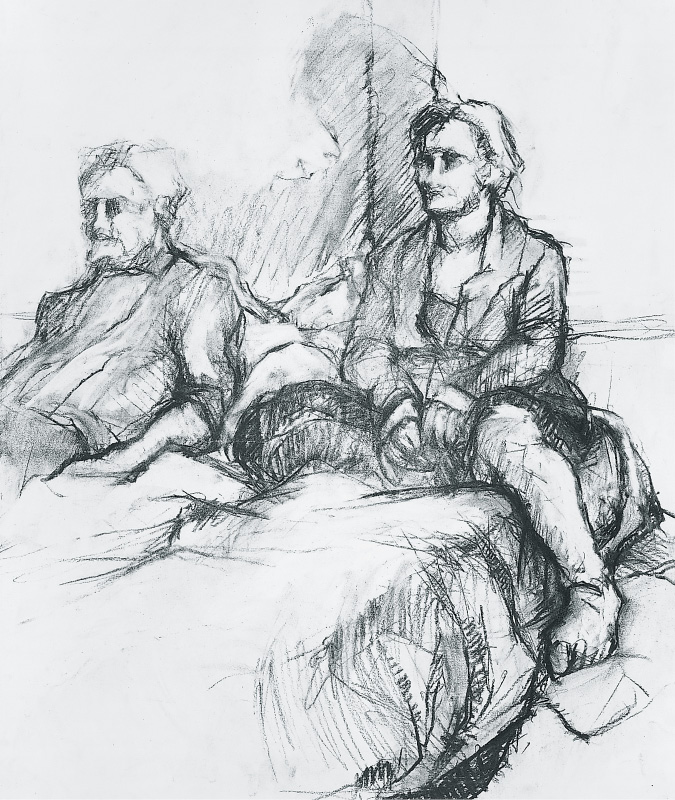

With the participation of family members, students reveal candid scenes in figures 6 and 7.

FIGURE 6

The couple is aware of being studied, but the drawing portrays them lounging with their attention fixed elsewhere, unmindful of their role. The volumes of their torsos and limbs press into the mattress and bedclothing, revealing body shape and language. Their barely defined features express the skulls’ influence on structure. Nonetheless, characteristic gesture (note the woman’s curled-under toes) and the clear sculpture of facial planes acknowledge likeness. A thin dark shape, beginning as a shadow cast by the bedclothes, ropes around the woman’s limbs and lashes onto the elbow of the man, creating a passageway through the drawing.

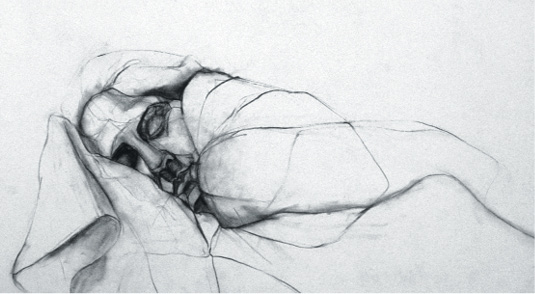

FIGURE 7

Head, body, and bedclothes nestle snugly against the bottom of the page. The curves of the bedding encase the body of the sleeping woman and leave her face as the focus; her features are assuredly carved in strong dark and light contrast—this planar modeling exists only in the face. Three deeply incised lines proceed outward from the mask of the face and hold it—like a faceted stone held in a setting.

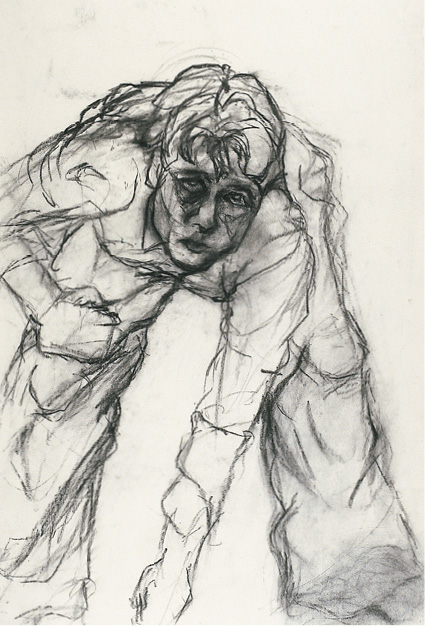

Examination of the gestures the body assumes while making a self-portrait occurs in figures 8 and 9. The head-on approach confronts the self and the viewer. In each the large drawing pad is placed horizontally while the mirror’s plane is vertical. The student must rely more on memory to reproduce her body posture and head position. (Her view of herself in the vertical mirror is no longer available as she bends her head in order to draw. Typically, both pad and mirror are vertical, and the drawer’s eye can scan subject and paper all-but-simultaneously.) Note that apart from blind-contour drawing, all drawing from observation utilizes some degree of visual memorizing.

FIGURE 8

Foreshortening conflates shoulders, chest, and hips into the top span of an arch in this self-portrait. The head, centered on this span, confronts the viewer. The axis of the head, echoed by the angle of the drawing arm, countered by the bent arm, hand on knee, all combine to heighten the figure’s animation.

FIGURE 9

In this drawing the student leans so far forward that her face seems to press against the picture plane as though it were a sheet of glass. Her features emerge through the dark tones that result from backlighting, challenging the viewer to discover them. Strongly contrasting tones of shadow and light reveal the volumes of the body and also provide a striking patterning by which the drawing may be read abstractly.

Two students take on the issue of extending the picture plane into the space in front of it by touching the mirror with one hand in figures 10 and 11.

FIGURE 10

The overlapped positions of the hand engaged in the drawing process further animate the drawing. The nude upper torso adds a dimension of intimacy—even voyeurism—to the act of self-portraiture.

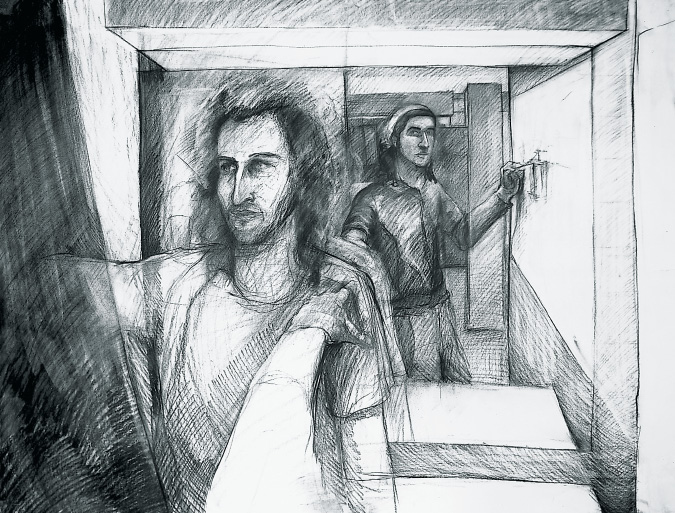

FIGURE 11

Lighting and framing provide a theatrical setting for two self-portraits. The back-to-back postures and the thrust of the arms suggest an artistic duel. The arm and hand touching the mirror acts as a vector, directing the viewer’s eye into the more distant center of the drawing. Here the author has played on duality by setting his self-portrait in the background within a receding series of darkened planes. The foreground contains the mirrored image of a classmate, his reflection set in light.

FIGURE 12

While the head is the central focus in the drawing, a cupped hand is included in the composition. The overlay of the fingers, drawn twice, lends the hand a subtle motion. The student presents herself, head in a turban, turned slightly away, eyes gazing back out—an homage to Vermeer; a young woman, lips barely parted—as if about to speak. The drawing tells of the next moment, and of time.

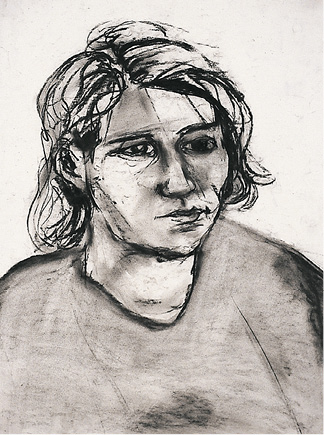

FIGURE 13

The Cubist push and pull of the planes of the face achieves animation. A diagonal seam cuts through the drawing, descending from the part in the hair, down through the forehead, along the left edge of the nose, cutting under to the indentation of the upper lip, and picking up underneath the sleeve. This diagonal seam enforces the tilted axis of the head, supported by the counter thrust of the neck and shoulders. The assured calligraphy of the tousled hair reveals the skull beneath.

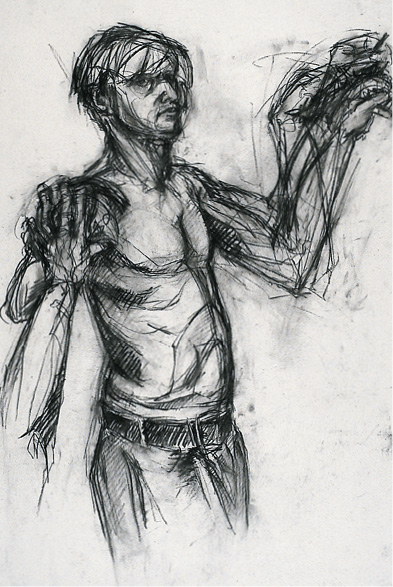

FIGURE 14

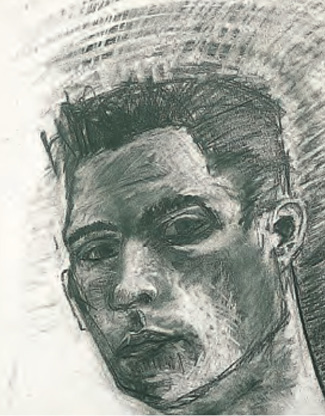

FIGURE 15

The gaze of the figure focuses strongly outward. The neck, entering from the bottom edge, together with the lines emanating in radial fashion from the skull, suggests a recent thrust upward into the space of the page. The boldly contrasting tones of planar modeling, the assertive handwriting, and the large scale of the head relative to the size of the page all speak of purposeful assurance.