DRAWING IN PRACTICE

POSTGRADUATE WORK

In the era before computer-generated graphics became the lingua franca of architectural practice, architects needed to be able to draw. They carried sketchbooks in which they noted ideas and kept travel journals for sketching buildings. The architect would think with drawing hand in motion. For some contemporary architects, the premiere pensée still comes from (or with) the hand roaming the paper.

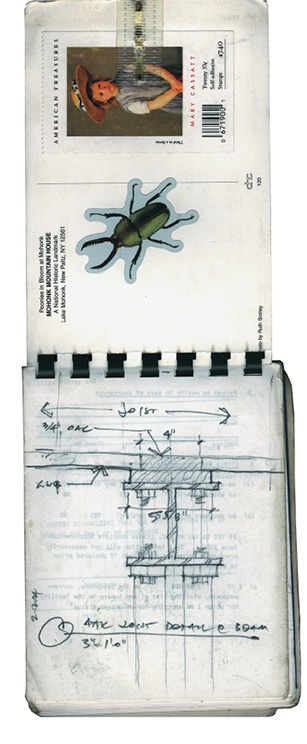

Paul Henderson of Sigler Henderson Studio has, for over a decade, manufactured his own series of sketchbooks composed of 8½ x 11 copy sheets of drawings, letters, and other paper memorabilia, folded into quarters so that the older material is hidden in the interior, or occasionally revealed (figures 2–4). The backsides of these works provide surfaces for further use—new drawings and ideas for projects, images of his family, mementos, or random items of visual appeal are collaged on them. The books hold a constant conversation between the architect’s personal and professional life.

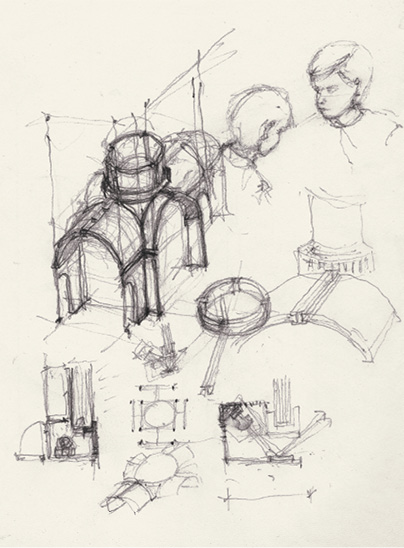

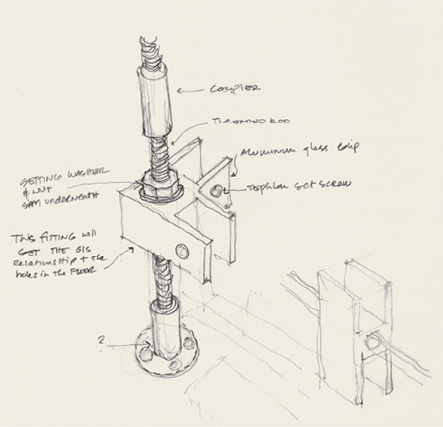

In François de Menil’s sketchbooks (figures 1, 5–7), he ponders details and structural elements and works out plans. In the pages concerning the Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum (1997), a thoughtful study of a child’s head appears (as if a child had just entered the room). The shape of the boy’s beautifully rounded crown resonates with the chapel’s dome.

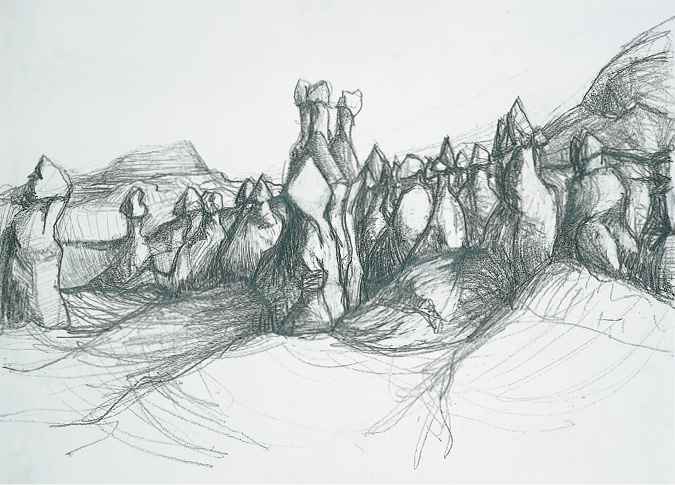

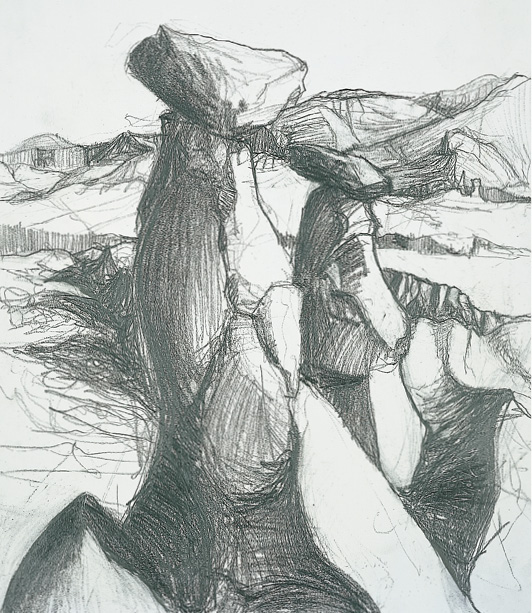

Two architects’ postgraduate investigations utilize drawing as a means to achieve a personal archeology, revisiting sites from their earlier lives, sites imbued with memory. In his Cappadocia landscape drawings, Firat Erdim revisits the wind-and-water-eroded landscape of his native Turkey. (Figures 8–9) The giant formations pictured in his drawings contain the history of Hittite temples and the remains of hidden cities and monasteries built by the first Christian colony founded by St. Paul. In drawing them Erdim mines his childhood landscape for visions that “have been coming back to me throughout and beyond my architectural education. Drawing has allowed me to explore a spatial unconscious.”

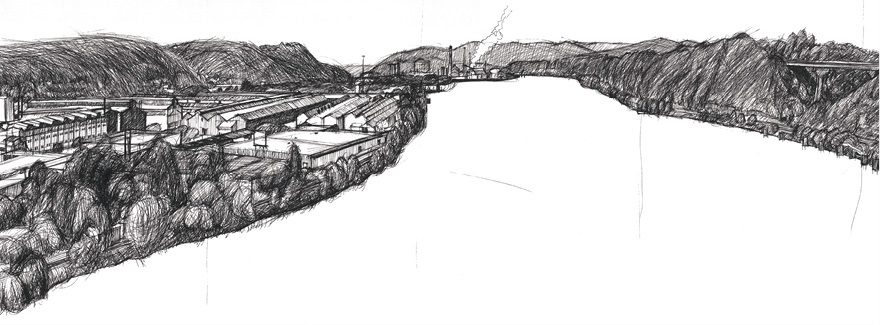

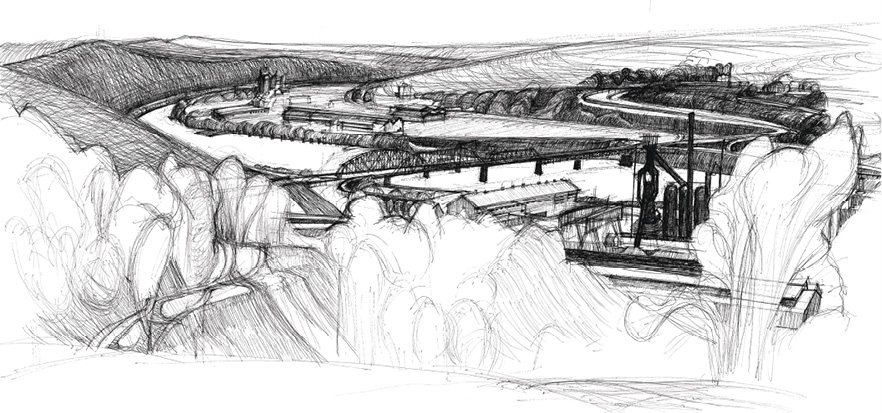

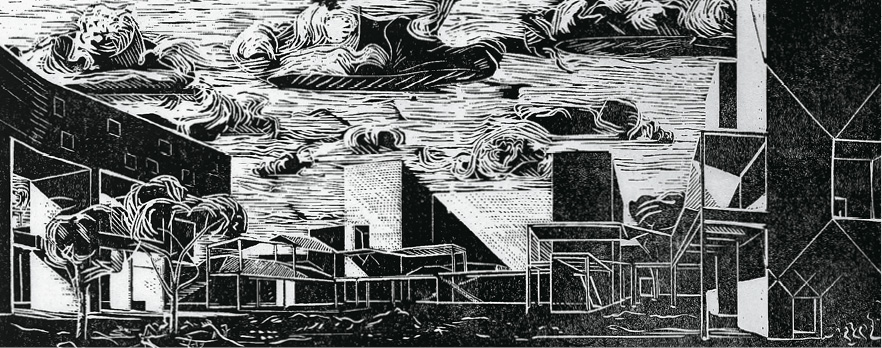

In his Pittsburgh industrial landscape series, James Hicks likewise revisits a remembered landscape. (Figures 10–11) A portion of that landscape was the site of Hicks’s thesis. In subsequent years he continued drawing from the site where his thesis project was located—unfolding the landscape as a map might show first one and then another portion of the region. His elegantly constructed drawings have the clarity of informed observation. Uninflected by atmospheric softening, the rocks, constructions, and trees are all of a cloth. Although the drawings display Hicks’s mastery of Renaissance perspective, the entire folio opens out the Pittsburgh landscape like an axonometric projection.

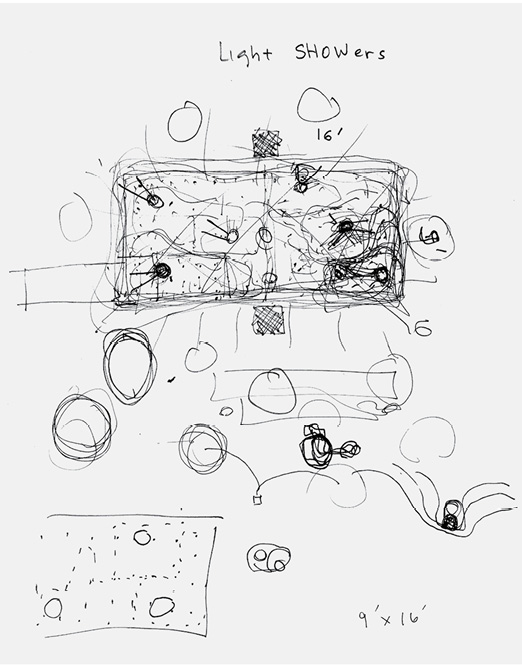

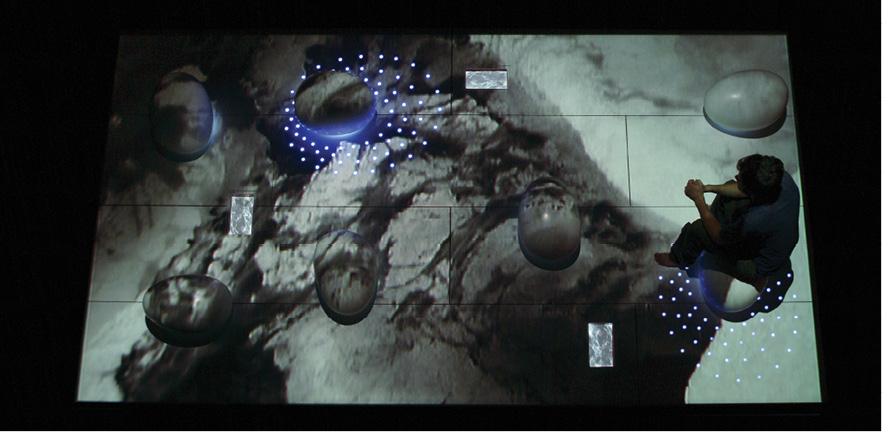

Morris Sato Studio provides plan views in both the concept drawing and the photographic image of LightShowers installation. (Figures 12–13) The drawing is a fluid investigation of the interchange between the project’s temporal and physical dimensions. While technical data will be plugged into later working documents, here Morris Sato explores the space created by light, water, sound, and human presence.

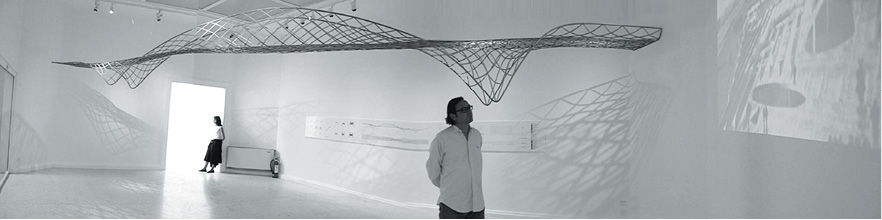

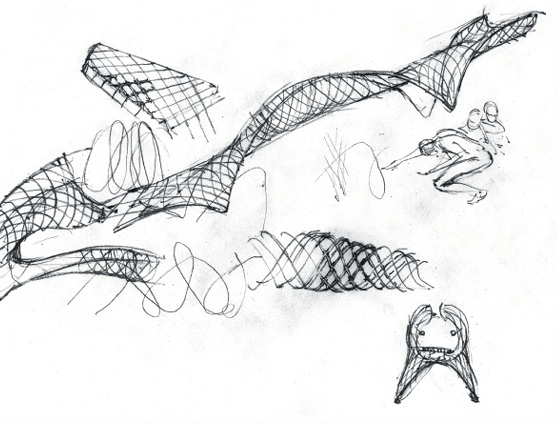

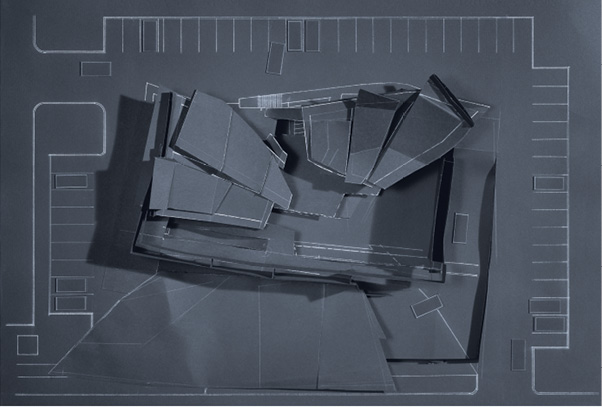

In the Fenquihi Station Bridge—Reiser + Umemoto’s project in Taiwan to be completed in 2010—there is the imprint of each of their early and career-long preoccupations. The illustration for the bridge gives evidence of Reiser’s immersion (since his student days) in drawings from the Renaissance. (Figure 14) Raphael is present in Reiser’s use of fabric to link together the discreet forms of human bodies. The basket-weave geodetic structure of the bridge integrates Umemoto’s fascination with weaving and fabric with Reiser’s attraction to the connection of fabric to body. (Figures 15–16) Spanning across the rails, the bridge blooms from an uphill roof to fold downward and sit on a station roof below.

Peter Lynch developed a language of representation consistent with his personal philosophy: “Architecture, like alchemy, is a process of transmutation [in which] mixed and formless matter is changed to material of lasting value.”1 Lynch avails himself of one of the most humble (and unforgiving) means of representation and reproduction—the linoleum block. (Figure 17) In his spare use of lines cut singly, grouped together or curving where he wills them, Lynch describes edge, light, and even animation. In a linoleum-block print of North Quad, clouds roll past sunlit facades.

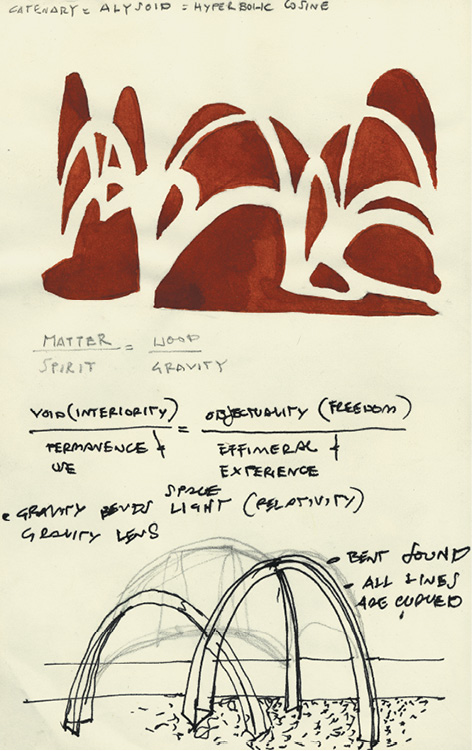

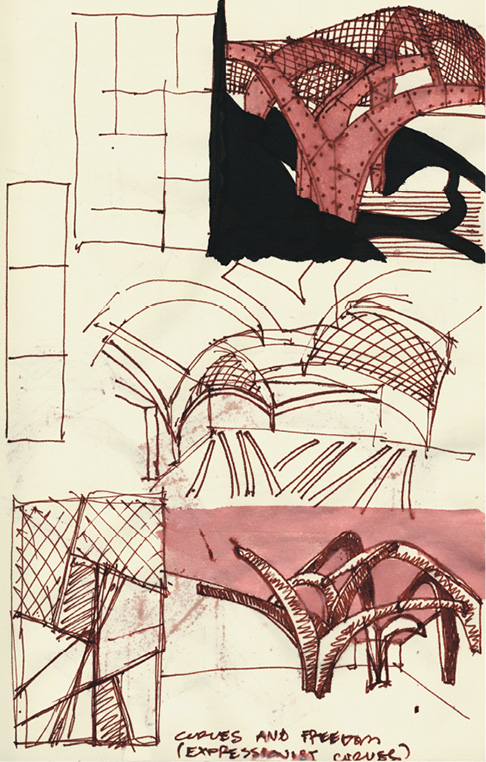

The several sketchbooks of Pablo Castro and Jennifer Lee reflect meditations on their project BEATFUSE!, OBRA Architects’ PS1 installation, 2006, in which seven interconnected shells create a condition of interiority in an open space. (Figures 18–20) Much as in a plan drawing in which interior elements might acknowledge the exterior walls, these shells rise up and address the walls of existing buildings at the PS1 site. The plywood-and-mesh structures encompass pools, water misters, and light strainers, which continuously draw shapes in the mist.

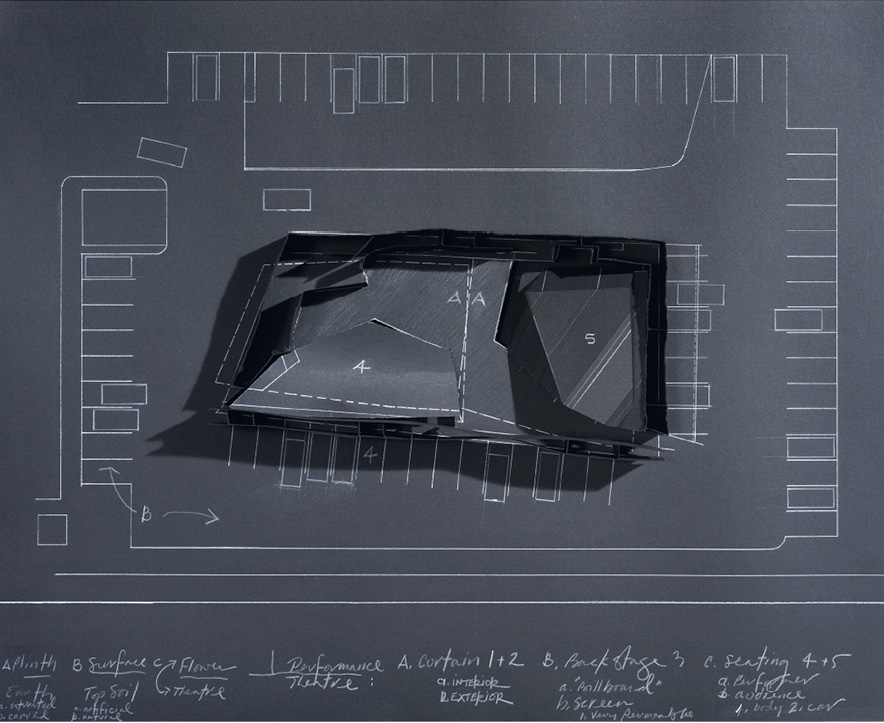

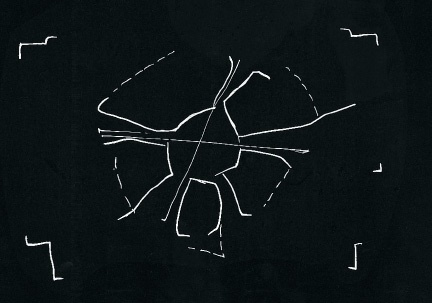

As a Rome Prize scholar in 1994, Karen Bausman invented a mode of representation that reconfigures the conventions of architectural drawing practice. In her designs for Warner Brothers’ Performance Theater (Los Angeles, California, 1999), she inscribes plan and section in one action on paper. (Figures 21–23) The sheet of paper is the site where the graphic and conceptual possibilities of the medium merge to forge a unique imprimatur.

In the work of these architects, the relationship between hand and mind is seamless. While several use drawing for representation and presentation (Bausman, Lynch, and Reiser + Umemoto), all use drawing as a means of expressing and clarifying their thought. For example, in the practice of Reiser + Umemoto drawing serves both generative and regenerative roles. OBRA’s many sketchbooks explore myriad ideas in an array of drawing media—watercolor, pencil, pen and ink, and markers. François de Menil keeps a sketchbook with him constantly.

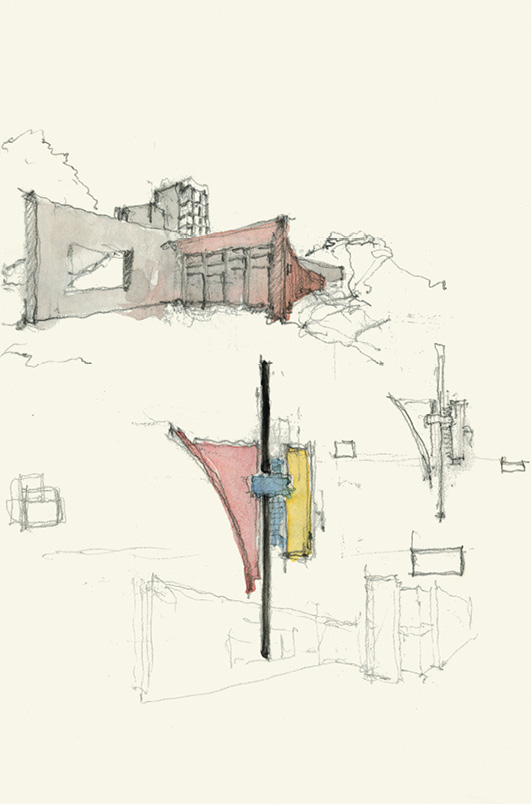

FIGURE 1

François de Menil, plan and study perspective of Foundation Watermill, an unrealized project, for theater director Robert Wilson, 1992. Pencil and watercolor on sketchbook paper.

FIGURE 2

Paul Henderson, construction drawing sketches for pocket door assembly and details in the architect’s home, 2005

FIGURE 3

Henderson, reproduction of a photograph of the architect’s wife and son, adjacent to a study for a country house with bascule decks that close the house when not occupied, 2003

FIGURE 4

Henderson, sketch of an attic joist detail showing the reveal between the ceiling and the steel beam in the architect’s home, adjacent to a bug sticker (a gift from the architect’s sons) and a Cassatt sticker from the United States Postal Service, 2004

FIGURE 5

François de Menil, studies for lighting of glass panels, panel supports, and suspension of the drum above the panels at Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum, Houston, Texas, 1993. Pencil on sketchbook paper.

FIGURE 6

de Menil, sketch for a 1:3 mockup of corner clip for glass panels at Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum, 1993. Pencil on sketchbook paper.

FIGURE 7

de Menil, apse and altar of Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum, 1997

FIGURES 8 and 9

Firat Erdim, Cappadocia drawings, 2002. Pencil on paper.

FIGURE 10

James Hicks, drawing of view from the McKees Rocks Bridge looking down the Ohio River towards Neville Island, Pittsburgh, 1997. Ink on paper.

FIGURE 11

Hicks, drawing of view from the Grand View Golf Club of the Duquesne and the Edgar Thomson steel works, Duquesne and Bessemer, Pennsylvania, 1999. Ink on paper.

FIGURE 12

Yoshiko Sato and Michael Morris, plan for LightShowers installation, Delaware Center for the Contemporary Arts, Wilmington, 2006.

FIGURE 13

Morris Sato Studio, photograph of plan view of LightShowers. Video images by Paul Ryan.

FIGURE 14

Reiser + Umemoto, drawing of view of plaza at Fenchihu, Alishan Mountain, Taiwan, with Raphaelesque figure grouping, 2003. Pen and ink wash on paper.

FIGURE 15

Reiser + Umemoto, wood model of bridge at Fenchihu at ¼ scale. Shown at the American Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2004.

FIGURE 16

Reiser + Umemoto, studies of Geodetic structure of bridge at Fenchihu, 2003. Colored pencil on paper.

FIGURE 17

Peter Lynch, block print of North Quad, a proposal for a high school and community college in Bushwick, Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Linoleum block print on rice paper.

FIGURE 18

Pablo Castro and Jennifer Lee, sketch for PS1 BEATFUSE! installation, 2005. Watercolor, ink and pencil on sketchbook paper.

FIGURE 19

Castro and Lee, PS1 BEATFUSE! installation, Long Island City, New York, 2006.

FIGURE 20

Castro and Lee, sketch for PS1 BEATFUSE! installation, 2006. Pen and ink wash on sketchbook paper.

FIGURE 21

Karen Bausman, plan drawing of Warner Brothers’ Performance Theater, Los Angeles, California, 1999. White pencil on black Fabriano paper.

FIGURE 22

Bausman, constructed drawing for Warner Brothers’ Performance Theater. White and blue pencil on black Fabriano paper. (see also p. 161)

FIGURE 23

Bausman, supermodel of Warner Brothers’ Performance Theater. Basswood and paper.