WHERE IT ALL BEGINS: PEAS IN A POD

Early on, I tell my students that I promise not to teach them anything “useful.” This, of course, grabs their attention; it is not what they expect. In architecture curricula drawing typically is viewed as utilitarian, a course adjunct to the design studio. In most schools drawing simply involves drafting techniques, nothing more. Only rarely is drawing regarded as expanding architectonic thought, as part of the thought process itself. Texts that link architecture and drawing together are generally how-to books. They deal with plan, section, elevation—or they set forth specific modes of illustration, such as perspective—but they do not address the experience of space or depth.

In my approach to setting up foundational problems, I find it important to teach concept, technique, and skill but imperative to recognize and value divergence. I teach Freehand Drawing to empower rather than “instruct.” Permeating through all the assignments and infusing all of the studio sessions is the concept of that metaphoric dimension—space. There is the obvious concept of space on the paper: it is blank or drawn upon. But how is one able to translate from the three-dimensional to the two-dimensional plane such factors as volume, transparency, and their interpenetration? The ability to master this is the underlying subtext of the course.

My first day of drawing class was a terrifying experience. Only seventeen, I had never contemplated an approach to drawing—much less thought about hanging any of my drawings on the wall and talking about them. Then there was Gussow, with this seemingly intimidating presence and a wide-brimmed hat to match. She was intensely serious about drawing. When it came to the first exercise, I practically carved the pea pod through the entire pad of newsprint. The drawing was miniscule, in the middle of an enormous sheet of paper. But even by the second attempt to draw from an actual pea pod, I was already beginning to study what I was seeing much more carefully. That study, or searching of sight, grew over the course of the year and still lives with me twenty years later. — STEVEN HILLYER

The very first meeting of the Freehand Drawing class provides the opportunity to establish the philosophy of the course. Drawing always begins on that very day. For the first several years, I handled that day in various ways, but in 1979 I happened upon a paragraph in the “Talk of the Town” column in theNew Yorker:

I was shelling peas from my garden the other afternoon, and the ancient figure (attributed to Rabelais) dropped into my mind: “As like as two peas in a pod.” I let it drop on through. I would be disappointed if I found only two peas in a pod, and I would be surprised if they looked exactly alike. Some peas are square, some are hexagonal, some are cone-shaped, some are disc-like, some are even round, and in almost every pod there is one pea, squeezed into the middle or off at one end, that is one-tenth the size of the others. Nature—in my experience with apples and green beans and tomatoes and squash and carrots and red roses and robins and oak trees—is given to variety more than to duplication. One has only to observe, to open the mind as well as the eye, to pierce the generalization. Peas look alike as Chinese look to Westerners or Westerners to Chinese.1

On that very first day, the students are the proverbial peas in a pod. Their names appear on a printout—as yet unattached to faces. Although differentiated by gender, clothing, and other surface attributes, they all appear wonderfully—and similarly—young.

EXERCISES

Draw a pea pod from memory and in such a way that it reveals the peas it contains. Any drawing medium may be used, and any size paper will do. Approximately 30 minutes are allotted for one or several drawings. Students are assured that this is not a test and no instruction is given.

Then actual garden peas—in pods, of course—are distributed. The pod and peas are drawn once more—this time from observation. Another 30 minutes is allotted.

The New Yorker paragraph is read to the class and copies of it are distributed.

Figures 1, 2, and 3 are a classic set of pea-pod drawings. They clearly illustrate the issues of visual memory and observation and the evolution from generalization to the particular.

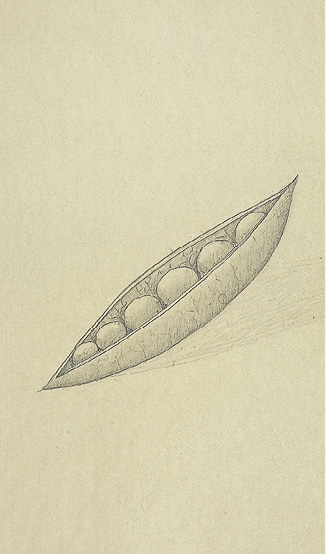

FIGURE 1

The canoe-shaped pea pod opens to reveal nearly identical spherical peas, somewhat graduated, like a string of pearls. The author’s veining of the pod’s semitranslucent walls and the notation of each wall’s slim ledge reveal his particular memory of an actual pea pod. Through the use of a faint shadow, there is only a tenuous attempt to anchor the pod to the surface on which it sits.

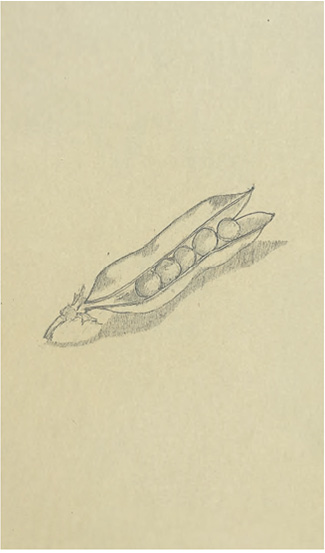

FIGURE 2

The drawing testifies to the impact of actual observation: the pod now reflects how its burgeoning occupants have influenced its shape. The cast shadow securely hinges the pod to the flat plane it occupies. The way the slender piece of stalk attaches the pod to the vine is well observed. However, the peas still retain their generic (now same size) roundness.

FIGURE 3

The pea pod ages. A small dried leaf is rendered in a spiraled curve. The vantage point is now from above—a more focused interior view. The peas are attached in an alternating pattern to either side of the pod’s opening, knocking them out of the strict alignment seen in the earlier drawings. No longer entirely individuated, the peas cast shadows on each other; the shadow shapes move the eye along the pod’s interior in a rhythmic fashion. The negative space—the leftover space between the peas—is delineated. The author has also created a mouthlike negative space at the split where the pod and stalk meet, echoing the open-mouth profile at the right created by the pod’s curled-out, drying ends.

ASSIGNMENT

Reread the paragraph and draw the pea pods once more for next class meeting. Draw two other drawings: some aspect of the space in which each student presently lives and a self-portrait.

The pea-pod exercise forecasts the philosophy that will infuse the entire year-long program. Apart from the message implicit in the brief New Yorker passage, the absence of direct instruction on the first day suggests that the students will in many ways become their own teachers. Observation is a key player in the course and a faculty that must be honed.

Were it not for the capacity to generalize, it would not be possible to draw or even to think. But it is through disciplined observation that differentiation is clarified. The detail, the texture, the various shapes, the angle at which the light hits, the location of one’s point of view are elements of study that lead a work from the generic to the specific and contain in them the magic of visual surprise. Surprise is the thing that caught your eye—the thing you did not expect to see. The question of what and how much to generalize, simplify, or edit out—and, conversely, what elements to emphasize, detail, and particularize—is crucial to the creative process. The balance struck between these two polarities must always be at the forefront of the critical discussion about the work.