BELL PEPPERS, GARLIC, BROKEN SHELLS, STILL LIFES

The pursuit of volume is of paramount intrigue in the art of drawing—the hand plotting out a web of lines to snare a three-dimensional form on a two-dimensional plane. The delight in seeing this fully rounded image emerge from the flat paper is equal only to the frustration and disappointment experienced when the drawing “falls flat.” When volumetric illusion is achieved and the object drawn seems to rise from the paper, we pronounce it “true to life.” Of course, it is not true at all. The paper remains forever flat. The form the drawing describes is an illusion; it is the magic of drawing that tricks the eye. Our purpose here is to learn magic tricks, to become magicians.

Concurrent with the first sessions of drawing from the live model, outside assignments are designed to expand the concepts of volume explored in life-drawing studio. When drawing the major masses of the body—head, chest, and hips—the first order of concern is their three-dimensional relationship around the central axis of the spine (see “Drawing from the Figure,” pp. 30–34).

In the assignments that follow the bell peppers, garlic, and broken shells should be arranged in multiples and their rounded volumes considered in relation to one another. The concluding still-life project takes these volume/space concepts to a more complex realm.

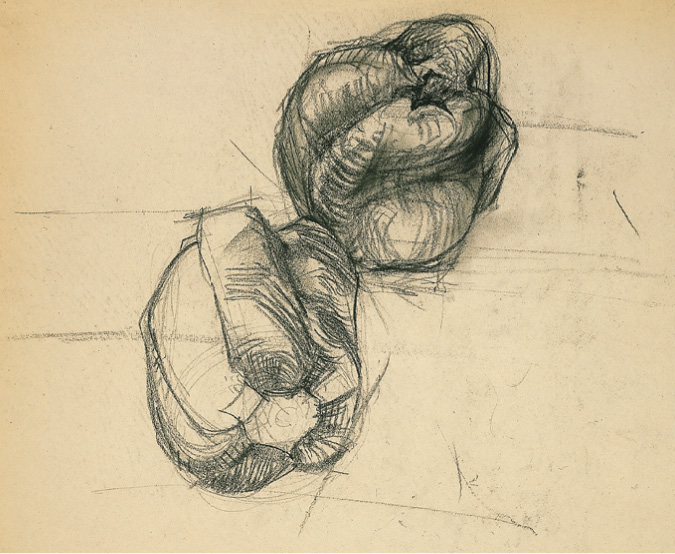

FIGURE 1

Bell Peppers

The fruit of the bell-pepper plant has long appealed to artists for its resemblance to the curves of the body’s fleshed-out contours. The bell pepper possesses another significant dimension: apart from the undulations of its surface curves, it is a housing. In botany this fruit is termed an ovary—the primal housing. To the student of architecture, its function as a container and its interiority are as worthy of investigation and preoccupation as its outward voluptuous form.

The wall of this rounded globe of curved ribs develops around a pulpy mass in which the pepper’s ovules or seeds are embedded. In the kitchen this pulpy mass is considered disposable waste, but it contains the botanic purpose of the plant. It is its future. The indentations delineating the curved ribs of the globe are an external expression of internal chambers, whose defining interior walls are formed by thin webs made of the same pulpy stuff as the central seed mass. As the pepper develops, these walls pull apart, and the chambers open, creating a vaulted hollow space. The pea pod’s snug housing and the bell pepper’s open chambers provide trenchant models for the organization of interior space.

It is critical early in the course to develop a dialogue between volume and void. Consider the object and the space it occupies; consider the space it contains—the void it houses and the manner in which this interior void opens (or does not open) to surrounding space. Also notice the object’s spatial relation to the next object and the next—and the next. To achieve spatial magic in a drawing, all of this must be attended to—seemingly at once. To this end, the assignments usually call for multiples of the object to be drawn; this enforces the necessity of considering space in the design strategy.

ASSIGNMENT

Obtain two bell peppers. Leave one intact. Cut the other into two—or more—pieces, anywhere from two equal halves to any number of slices and proportions. Set the several pieces on a surface in a random arrangement, and draw them simultaneously as though there were an invisible spine connecting them. Freely use lines that wrap around the peppers’ shapes. Do not draw only those lines that describe outside contours and rib indentations. Lines should also serve to indent the hollows and sculpt the bulging contours. As the eye travels back and forth from the whole pepper to the sliced portions, the hand should take account of the spaces between the pieces. Lines should describe, as well, the concavities of the segments’ hollow interiors. For each of these five drawings, rearrange the peppers or change your vantage point. Set a strong single light source on the arrangement throughout the assignments. Draw five drawings with vine charcoal. 18" x 24" (or larger) newsprint pad. 5 to 10 minutes each.

Make a blind-contour drawing of at least two of the pepper pieces. In this method the eye slowly follows any line on the surface of the pepper—or its revealed interior—as the hand and pencil slowly record the eye’s observation. In its classic form, a blind-contour drawing is made without the eye ever engaging the page. In the method we will employ here, the student may glance down rapidly—but infrequently—to judge the progress of a line. Drawing should then momentarily cease, starting again as the eye quickly resumes its focus on the line being studied. Scrutinize contours—i.e., outlines of shadows, highlights, details, and outer edges—equally. As progress should be painstaking and slow, consider the drawing finished—no matter how incomplete—in 1 hour. Freshly pointed pencil on 18" x 24" white paper.

Do a freestyle drawing. Any manner of drawing, provided the drawing is from observation and includes the pepper and pieces. Any drawing medium on any paper. 1 hour or more.

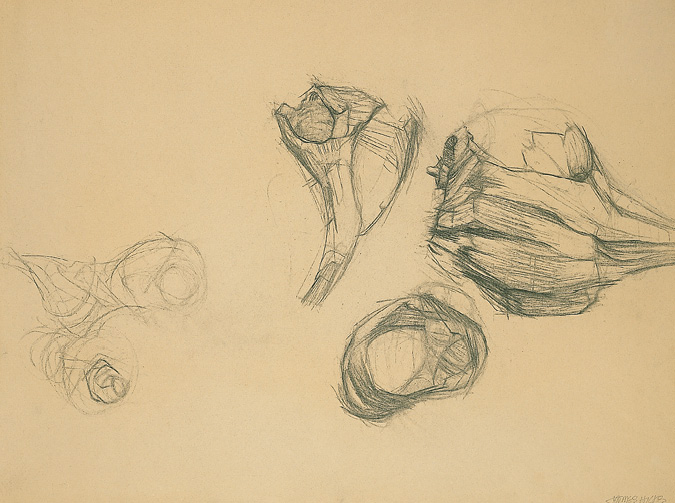

FIGURE 2

In this rapid study, a pepper is doubled over rather like a crouched human body—a challenging choice for a beginning student. The concavity of the bent forms is made emphatic by the gathered charcoal markings that follow the contours of each of the peppers’ concavities and convexities. The missing lobe extracted from the pepper to the left remains a blank space and does not appear elsewhere on the page to give the pair a spatial reference. Here the intrigue with volume exists in its exterior expression.

FIGURE 3

In this response to a blind-contour exercise, the author’s eye has traveled along the edge of any observable shape making very little distinction between lighter or darker inflections of line—i.e., the shape of a highlight or shadow on the pepper’s surface or the overlapping rings of shape created by the peppers’ cast shadows are described with a similar surrounding edge.

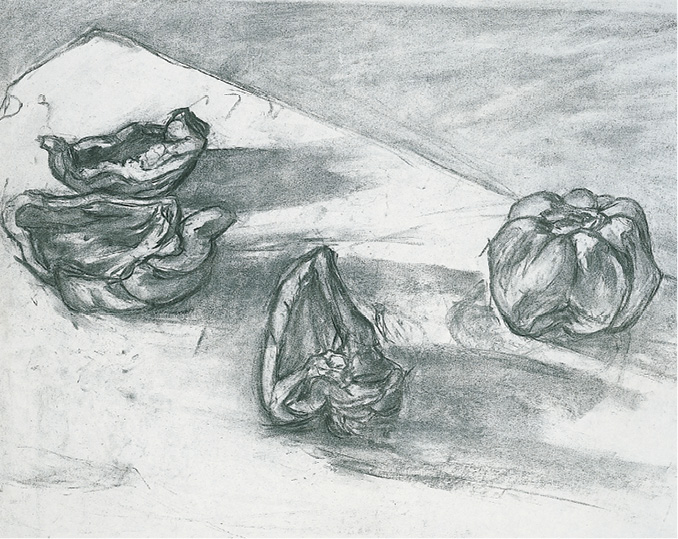

FIGURE 4

This freestyle study reveals the author’s intense curiosity regarding the interior chambers of the sliced pepper. In true architectonic fashion, a section cut horizontally across the top quadrant of the pepper reveals the pulpy central mass with its embedded seeds. The drawing notes how pulpy walls emanate from this center to the exterior wall, defining the pepper’s three chambers. The contrast between the satin gloss of the pepper’s exterior surface and the texture of its bumpy interior are also carefully noted.

FIGURE 5

The left pepper in this freestyle rendition is cut along the indentations of its chamber walls. The leftmost piece, only partway severed, suggests that this segment is in the act of unfolding. This lends animation to the semicircular composition, held together by the contrasting statement of the plane of the table, whose topmost corner creates tension as it points toward the paper’s edge. Charcoal tone is employed with eloquent gradation to indicate depth.

Garlic bulbs provide another opportunity to examine body-referent forms. Grouping and regrouping three or more bulbs (and a number of their separated cloves) creates a continuing space/design strategy. The structural arrangement of an individual garlic bulb is markedly different from the walled hollow of the bell pepper. Here, a compact mass of curved cloves is attached at bottom to a disc-shaped base from which a mop of roots descends. The compacted cloves are shaped snugly to one another around a very slender central core. The flesh of each clove is wrapped in its own skin; four or five translucent skins provide overall structural support, packaging the cloves in their wrapping. Each of these skins girdles the bulbs’ gathered mass then twists about at the top, forming a stalk.

ASSIGNMENT

The assignment for drawing garlic bulbs follows the format given for the bell peppers. Leave two of the bulbs intact; extract several cloves of the third. Draw the three bulbs together with the separate cloves (virtually at once in the 5 to 10 minute drawings). Materials follow the same format given in the bell-pepper assignment.

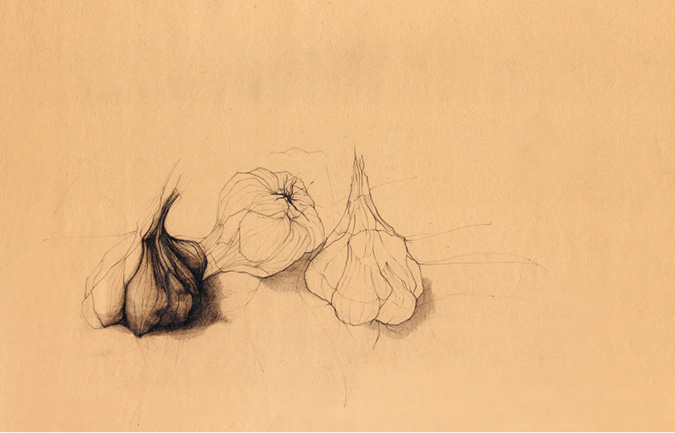

FIGURE 6

Three complete garlic bulbs are each drawn with careful attention—the center and right bulbs in a linear mode derived from the blind-contour exercise. Several of the three garlics’ thin skins appear to have been removed so that the burgeoning cloves might be explored in all their interdependent complexity. The presence of a remaining translucent wrapper is made evident by the elegantly drawn striations that follow the cloves’ curves. The skin of the left garlic is the only area rendered in tone suggesting a deeper local color than the smooth unwrapped cloves on its left. (Local color is the surface color of an object—white, grey, black, red, green. In drawing, local color is translated to grayscale, to the tone it might appear in a black-and-white photograph.) The vertical center of the composition is just left of the right bulb’s ascending twist of skins, and the greater bulk of the almost-symmetrical group is pushed to the left of the page and held in balance by the large negative space on the right.

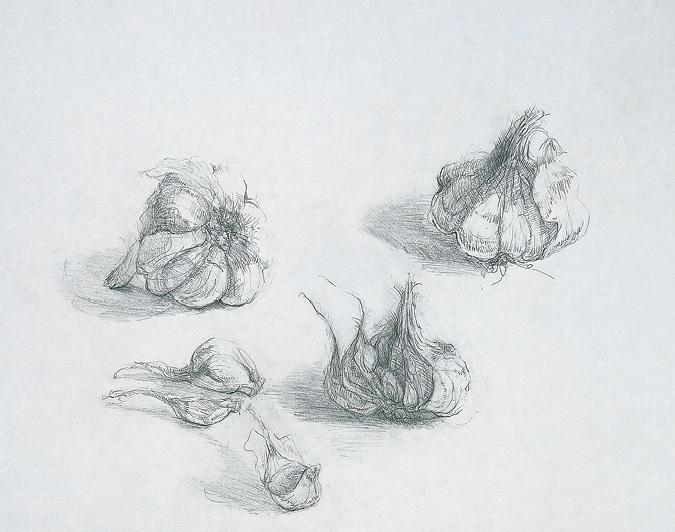

FIGURE 7

The four bulbs are in varied postures, but in each the fascination rests equally between the mop of root mass and the intricate configuration of cloves. So much detail might prove distracting were it not for the passageway the dark shadow tone provides. (Passageway is a strategy for leading the viewer’s eye through the drawing. It can be achieved by linking darker shapes or employing lines that continue from one object to another.) If one squints one will note there are three shapes of connected darker tones that join to one another. A secondary lighter gray describing cast shadowsjoins the bulbs into two major groups and also creates a hinge to the ground plane.

FIGURE 8

Each garlic bulb and separated cloves are presented in varying stages of deconstruction from whole to unwrapping to pulling apart. The story of this process animates the drawing in a zigzag gesture from top right downward to a lone foreground clove. Each step is superbly documented and sensitively drawn, but it is narrative rather than compositional structure that holds the drawing together. Note especially the garlic coming apart to reveal its many separated cloves—drawn as if the event of separating were generated from within the garlic itself.

Knobbed Whelk and Moon Snail Shells

Approximately one hundred miles east of The Cooper Union, the Long Island shores are punctuated with broken whelk and moon snail shells. (Entire shells are rare.) Unbroken shells in all their variety have long attracted human attention. Widely used as money, for jewelry, and as collectibles, their caverns and curves have delighted the eye and hand for millennia. For one who draws they offer an opportunity to examine the dialogue between volume and captured space. Rembrandt’s haunting etching of a lone auger shell is a striking example of the undamaged shell’s enchantment.1

However, it is the broken shell that will attract our attention here. Both their plentitude and their fractured condition make them worthy objects for an architecture student’s drawing investigation. The seashell is at once armor and housing for its occupant, the mollusk. In a broken state the intricacy of the internal structure, and its former use, is revealed. In a majority of found shells, dashed by waves or attacked by gulls, both the concave walls and the convex inner chambers are simultaneously revealed. Certain shells, less frequently found, are ground down by sand over time to a spiraling inner core—a twisting spine just hinting at the walled chamber that once wrapped around it.

The term spiral, both a noun and a verb, embraces form and declares a continuous curvilinear motion. All shells in embryonic state are formed around a spiral.2 In addition to the twisting counterpoint of inner core and outer chambers, the outer surfaces of the walls are themselves inscribed with the spiraling grooves of the shell’s formation. The knobbed whelk shell’s protuberant bumps punctuate yet another spiral formed by the shell’s outer ledges. These features of the shell’s formation seem to guide the hand as it draws.

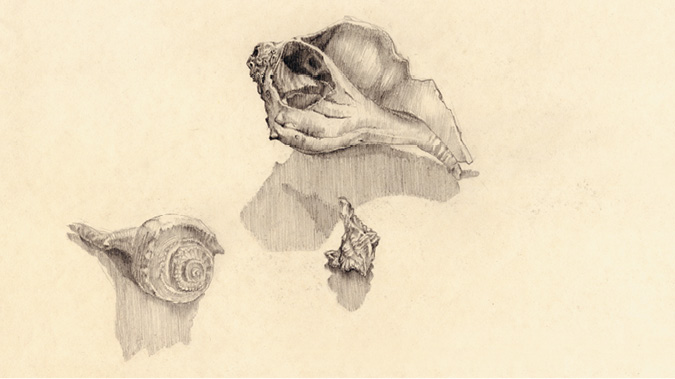

FIGURE 9

On the far left of the page is a rapid study; a more fully realized drawing appears on the right. The two present a dialogue on the development of a drawing. The soft, searching hand of the rapid study spins many lines around the spiraling circumferences of whelk and moon snail shells. The darker, more developed portion of the drawing on the right was begun in the lighter, more tentative fashion of the smaller sketch on the left. The broken portions of the center whelk shell and the moon snail shell beneath it provide an excellent window on each shell’s spiraling core. In its tonal and lit variations, the drawing also predicts the use of the plane to examine form (discussed in “Giacometti and Planar Drawing,” pp. 66–69).

Where portions of the shell have been broken away the edges are jagged, in contrast to the shell’s swelling curves. This suggests that planar lines might be employed, together with the curving spiral, to capture the shell’s spatial complexity.

ASSIGNMENT

The broken-shell assignment follows the format given for the bell-pepper and garlic drawings in all portions and all media. Use a minimum of three to five broken shells, and draw them together simultaneously.

Note: In the blind-contour portion of the assignment, draw quite slowly. Let the eye and hand travel from one shell to another, neither hurrying the investigation nor being concerned with the completion of the drawing.

FIGURE 10

The author of the drawing chose shells with minimum damage. The center whelk shell sports only the smallest round break—suggesting a spy window or peephole. It is the volume of the shells, their function as containers, that is of interest here, as the top right moon snail shell with its spiraling channel clearly indicates. Tonal gradations enhance the configuration of the shells (each positioned differently), enforce the shells’ roundness, and create cast shadows that marry the shells together and distinctly define the ground plane.

FIGURE 11

The drawing declares the author’s fascination with details, presented as minor structures supported by a major structure. The eponymous knobs that punctuate the whelk shell’s outer ledges are clearly articulated, each with its particular and volumetric dimension and precise location on the spiraling ridge. A break in the wall of the largest shell provides a window on the curved and satin-surfaced interior.

At the start of the 1993–94 academic year, John Hejduk commissioned all of the five design studios to explore the same problem: the design of a house. In fifth year, the thesis class was given the topic of still life as an avenue into “the house.” As a response, a still-life project was assigned in Freehand Drawing to encourage dialogue between the first-year and thesis classes. In preparation the first-year class studied many of the great stilllife painters—notably Jean-Baptiste-SiméonChardin, Paul Cézanne, Georges Braque, and Giorgio Morandi. The two following examples of student work did not chronologically follow the pepper and garlic assignments—although they fit here schematically. They were completed later in the semester when concepts of passageway, density, transparency, and space had been explored.

FIGURE 12

Transparency and overlap are the most striking features. In exploring the relative location of various items—the bottle, the crate, pepper segments, etc.—they were drawn and then redrawn, their overlap lending the work both transparency and animation. The dense center arena of the drawing has an implicit grid structure suggested by the actual grid configuration of the crate. As the eye follows darkened linear paths through the jumble of fabric, fruit, and containers, a cityscape comes to mind.

FIGURE 13

Landscape serves as a metaphor here, while the strong vertical of the bottle at the top suggests a tower. Linear pathways lead from the rounded fruit and vegetables to the surrounding tousle of fabric in which they are nestled. The round forms, the area of gray hatching suggesting a valley, and the light nuanced handwriting of the surrounding fabric all speak of a more open environment than figure 12 proposes.