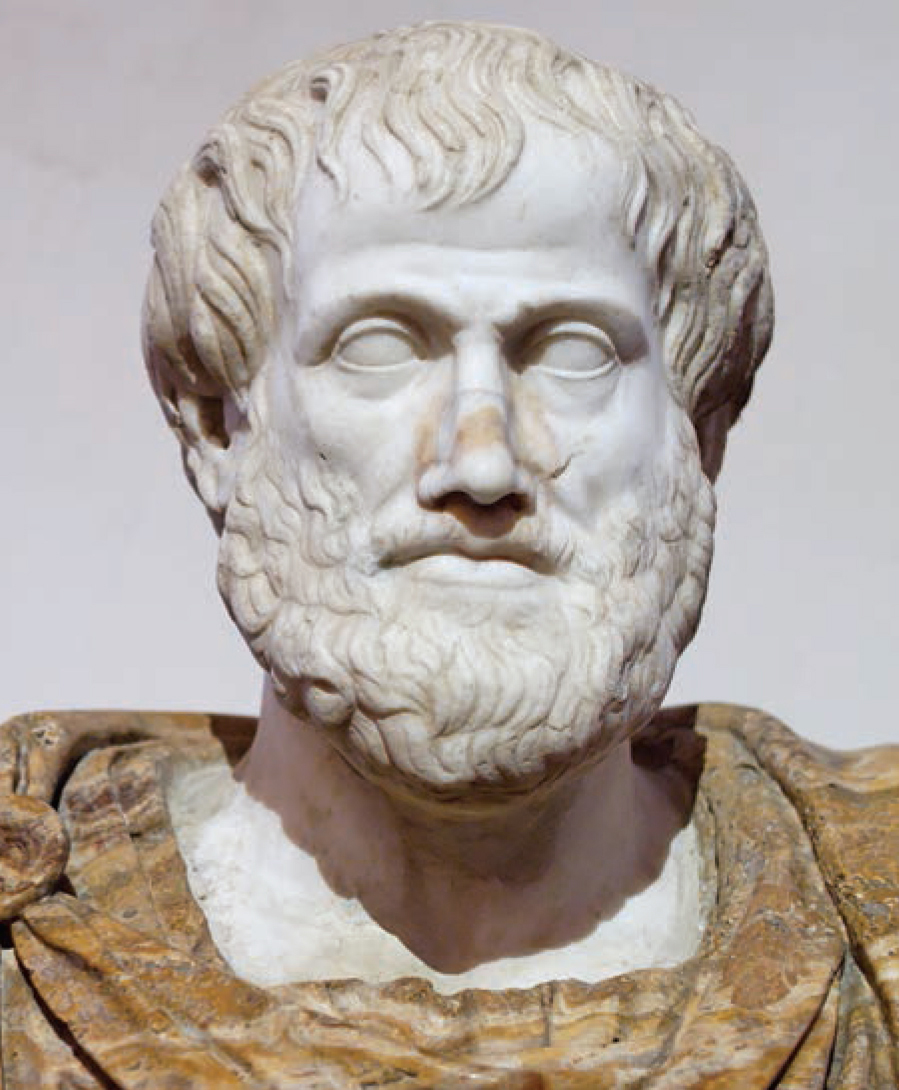

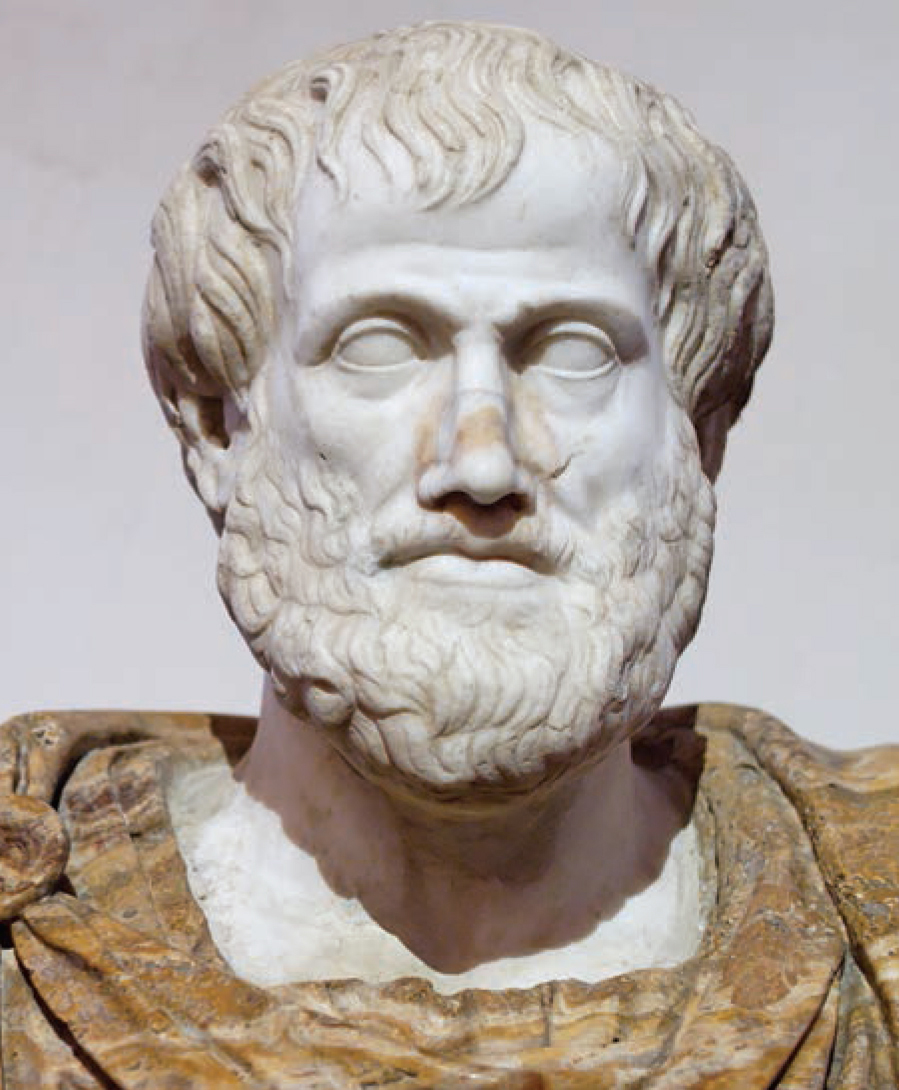

The original bronze bust of Aristotle by Lysippe has been lost, and, like most of what we know about the master philosopher, has been passed down as an Imperial Roman copy.

4 : Lysippe’s bust of Aristotle

c. 330 BC

The original bronze bust of Aristotle by Lysippe has been lost, and, like most of what we know about the master philosopher, has been passed down as an Imperial Roman copy.

Birds must have always had an important role in human affairs, not least in the uses of their meat and eggs for food, their depredations on crops and livestock, their feathers for clothing and decoration, and their migration and dispersal as an indication of changing seasons and weather.

This last point in particular may well have inspired those of a philosophical bent, and it is in what remains of the work of one of the greatest ancient Greek writers and teachers, mostly preserved as medieval manuscripts, that we find the first written descriptions and musings upon natural history and the subject’s most notable signifiers – birds.

Aristotle lived from 384 to 322 BC, and was the first known writer to undertake what we would recognise as a systematic study of birds, though his legacy also includes a truly polymathic range of subjects from geology to poetry, physics to logic, and theatre to pioneering work in zoology. From the point of view of the modern birder, it is notable that much of his research was original and took place in the Aegan on or around the migration hot-spot island of Lesvos, producing enduring compilations of observation, empiricism and myth entitled Inquiries on Animals, On the Generation of Animals and On the Parts of Animals.

Though they were informed as much by hearsay as study, Aristotle took great heed of the field experience of farmers, fishermen and hunters, and their insight into the songs, food, distribution and seasonality of birds. He also classified the known species according to the form of their feet (an ecologically logical start point) and the nature of their food, dividing them into seed-eaters, insect-eaters and meat-eaters. He was astute enough to realise that the physiology and anatomy of birds are informed by their environment, noting that size was influenced by climate and that some birds were altitudinal migrants, that different plumages existed at different times of the year, and even the parallels between reptile scales and feathers.

However, he also wrote that swallows, storks, woodpigeons and starlings hibernated after shedding their feathers, and that the Black Redstart moulted its plumage to become Robins. Swallows were also believed to be able to heal punctured eyeballs and nightjars to suck blood and goats’ milk. Aristotle was, though, able to refute some of the myths of the day, such as the belief that vultures hatched out of the ground.

Aristotle was a giant of his time, but many other works of natural history were written in ancient times, and are mostly now lost. However, the knowledge contained in more than 2,000 of these was compiled by the Roman historian, Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, 23 to 79 AD), whose Natural History contains much early ornithology, particularly in its 10th volume. His classification begins with Ostrich, which he believed to be closely related to ungulate mammals, and Common Crane. The mythical Phoenix was included, Pliny raising doubts about its existence, though he still maintained that some migratory birds hibernated (a belief that persisted well into the 19th century in western Europe).

Pliny’s encyclopaedia, along with the anonymous Second Century text Physiologus, shows that empirical science was gradually developing almost universally in the great ancient civilisations. However, the rise to power of dogmatic religious authority would virtually scupper this until the 15th century, when the ancient texts would be rediscovered and help fuel more radical and widespread scientific enquiry, and with it revolutions in zoology and the origin of ornithology as we know it today.