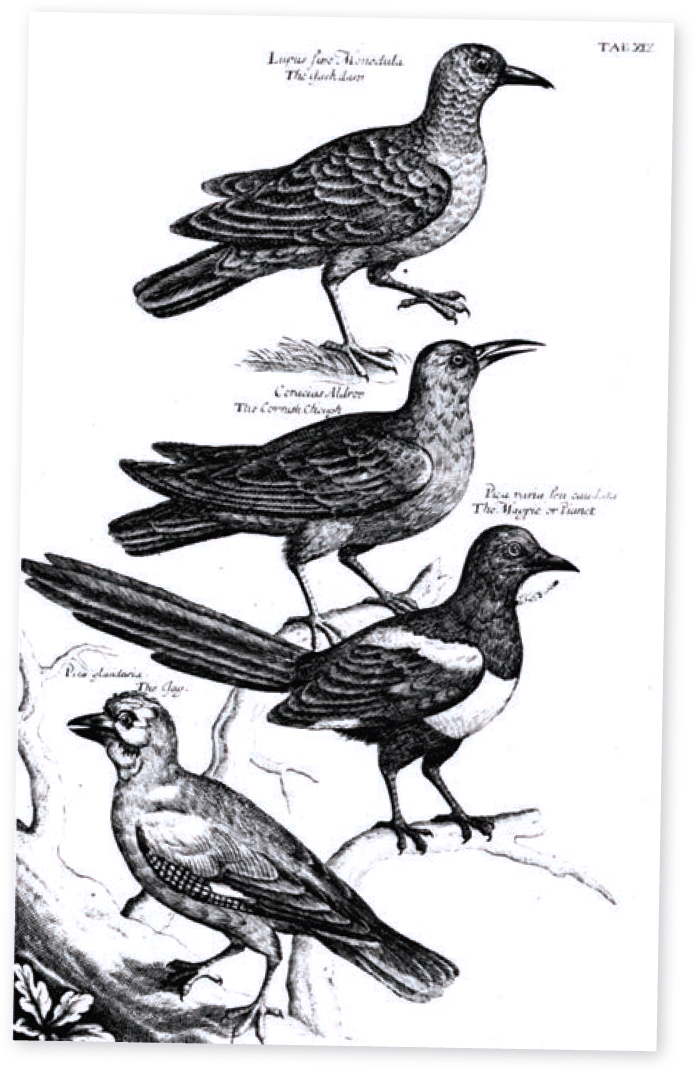

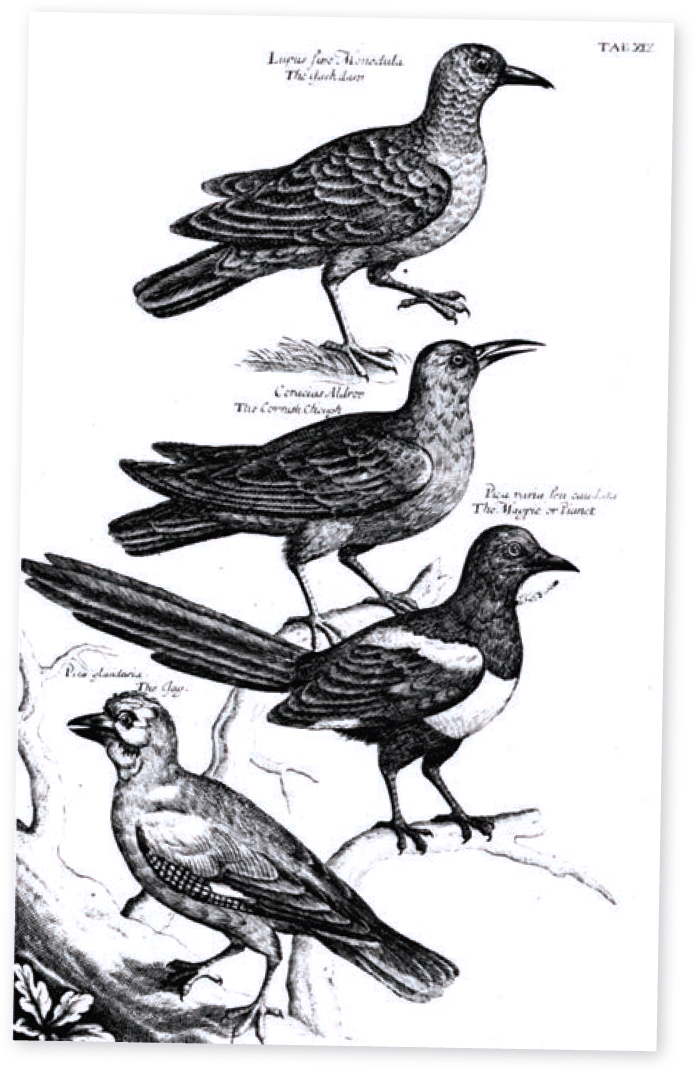

The corvid plate from Ornithologiae Libri Tres; Willughby died of pleurisy as the work was in progress, but Ray was able to see it through to publication and success.

9 : Ornithologiae Libri Tres by John Ray and Francis Willughby

1676

The corvid plate from Ornithologiae Libri Tres; Willughby died of pleurisy as the work was in progress, but Ray was able to see it through to publication and success.

In 1676, the naturalist John Ray published a book he had co-written under the sole name of Francis Willughby, in tribute to his dead friend, though it is of little doubt now that Ray was also a major author. Its 441 pages in three volumes contained the first systematic attempt to comprehensively itemise the British avifauna. It encompassed about 230 species, though some foreign forms were mentioned and several names were sometimes used for single species. However, it had an unprecedented scientific rigour for its time and classified birds according to their detailed physical characteristics, including plumage. A few other lists had been attempted in the two previous centuries, including a fairly full but somewhat folkloric British list compiled by Christopher Merrett just 10 years earlier, suspected to have inspired Ray and Willughby to improve upon it.

The two ornithologists could hardly have come from more disparate backgrounds, with Ray the son of an Essex blacksmith whose Cambridge education was paid for by a philanthropic clergyman, while Willughby came from land-owning aristocratic stock.

Despite Ray’s social ‘inferiority’, it was Willughby who came under the influence of Ray’s charisma and mental discipline as they began working together after meeting at Trinity College. Ray, though ordained, was a religious non-conformist and resigned his clerical status to travel Europe with his newfound companion, and during their travels they collected specimens and dissected them on the road. They kept detailed notes of their examinations of species like Great Bustard and Black Stork, observing such features as feathering, musculature and parasites.

Ray was not financially secure and had to work as a private tutor (sometimes for Willughby’s children) to raise funds for his travels and studies. The somewhat frail Willughby died at the young age of 37, leaving Ray a then-significant annuity of £60. The early death spurred Ray into writing up their notes as Ornithologiae Libri Tres – literally three books of ornithology – published in Latin and containing a surprising quantity of knowledge. They used a binary classification, dividing their subjects into landbirds and waterbirds, and using their observed physical characteristics to further subdivide into classes.

Landbirds included crooked-beaked diurnal birds of prey (including shrikes and birds-of-paradise), nocturnal birds of prey and parrots, and straight-beaked ratites. Waterbirds were divided into marshland species with dagger-like bills, crooked- or straight-billed waders, those waders with medium-sized bills, and plovers (with short bills). A further waterbird division was that of open water species, including groups for Eurasian Coot and Moorhen, flamingo and Avocet, auks, cormorants and Gannet, and more. It wasn’t a bad start, though some names are confusing in a modern context, and others, like ‘arsfoot’ for grebes and divers, amusingly prosaic.

It seems likely, on Ray’s own admission, that Willughby was the more meticulous observer; Ray entered his detailed plumage notes into the book almost untouched. Both can be looked on as the fathers of modern bird studies and observation, and they made many important advances.

However, the first truly logically systematic list of bird would be established by a Swedish botanist in the following century (see pages 32-33).