Commercial flying is now becoming more expensive, but for a few decades it has been cheap enough to open up the globe to almost anyone willing to explore it, including many thousands of birders.

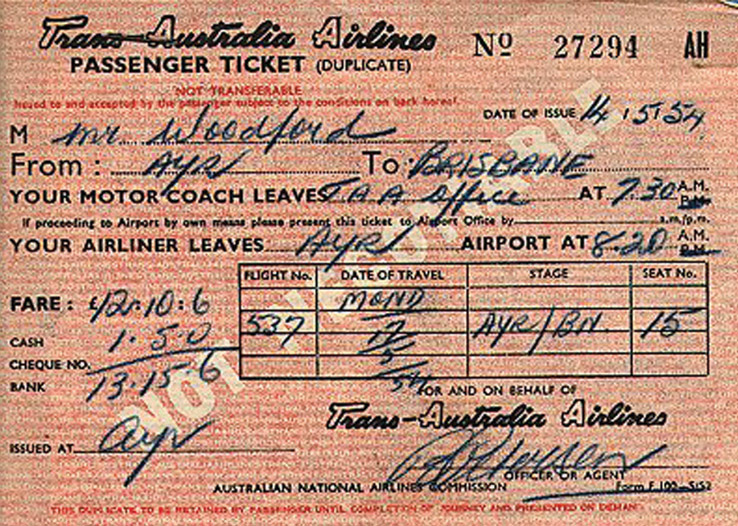

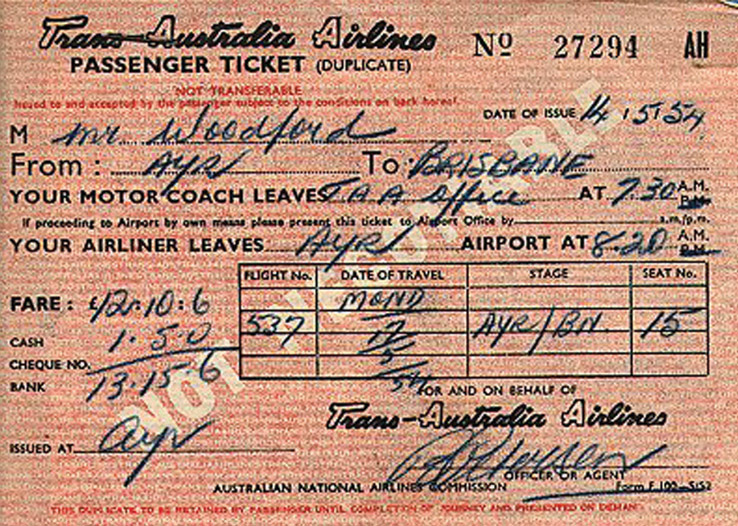

45 : Aeroplane ticket

1911

Commercial flying is now becoming more expensive, but for a few decades it has been cheap enough to open up the globe to almost anyone willing to explore it, including many thousands of birders.

Before the availability of commercial air flights, foreign birding was still largely the preserve of the well-off and the sponsored, and to experience the birds of other continents those of modest incomes and connections were best served by joining the armed forces or the merchant navy.

The first commercial flight took place in 1911, but it wasn’t until 1926 that this mode of transport was finally viewed as affordable and safe. In the USA, subsidies to encourage mail flights to take passengers and fairly strict safety regulations to build customer confidence meant that, by 1930, there was a flourishing and recognisable air industry. United Airlines featured stewardess service by trained nurses who also balanced mechanical repairs, refuelling and cleaning of the aircraft with their in-flight duties, including the serving of meals and drinks.

With a booming airline industry in the post-war years, the door was open for overseas holidays specifically to watch birds. In 1965, Lawrence Holloway set up such a trip under the banner of Ornitholidays to Camargue, France – a bird-rich area very much viewed as an exotic location in pre-package tour days. This was quickly followed by an Austrian trip, thereby establishing a still burgeoning market for specialist birding holidays and what are now often known as ecotours.

Some companies emphasise the holiday aspect almost as much as the birds and wildlife, but with the growing popularity of world listing, and obsessed birders realising it is now actually possible to see most of the world’s bird species, other companies have established more ‘hardcore’ reputations with itineraries which concentrate on getting as many ‘ticks’ as possible.

In essence, though, the broad concept of ecotourism began perhaps a decade before that first Ornitholidays venture, and can be traced to the formalisation of game hunting in the 1950s when the market for recreational shooting of trophy wildlife led to the demarcation of game reserves, protected wildlife areas and national parks in some of the countries of sub-Saharan Africa. The idea of ecotourism is now long divorced from its uneasy arranged marriage with the big game hunter, though such ‘sport’ remains popular in certain quarters, and many reserves are still maintained with this purpose in mind, incidentally protecting local wildlife.

In some areas, however, reserve operators now deem conservation more important than hunting, with the latter viewed as a necessary evil. In 2013 Zambia finally banned big cat hunting, its tourist minister Sylvia Masebo stating: “Tourists come to Zambia to see the Lion and if we lose the Lion we will be killing our tourism industry. Why should we lose our animals for $3 million a year? The benefits we get from tourist visits are much higher.”

Birding contributes billions of dollars to different countries’ economies – its popularity in the USA alone is estimated to generate $24 billion and employ more than 60,000 people. In many parts of bird-rich Africa and South America, bird guides who have turned their innate local ornithological knowledge – sometimes derived from hunting skills – into real expertise are among the high earners in their local communities, injecting cash into their area and providing secondary employment in tourist services.

Birders are at the forefront of the dissemination of ecological awareness on a global scale, and can also be said to be spreading a kind of grass roots diplomacy, an international understanding at a personal level, travelling further into countries and regions than even many backpackers.