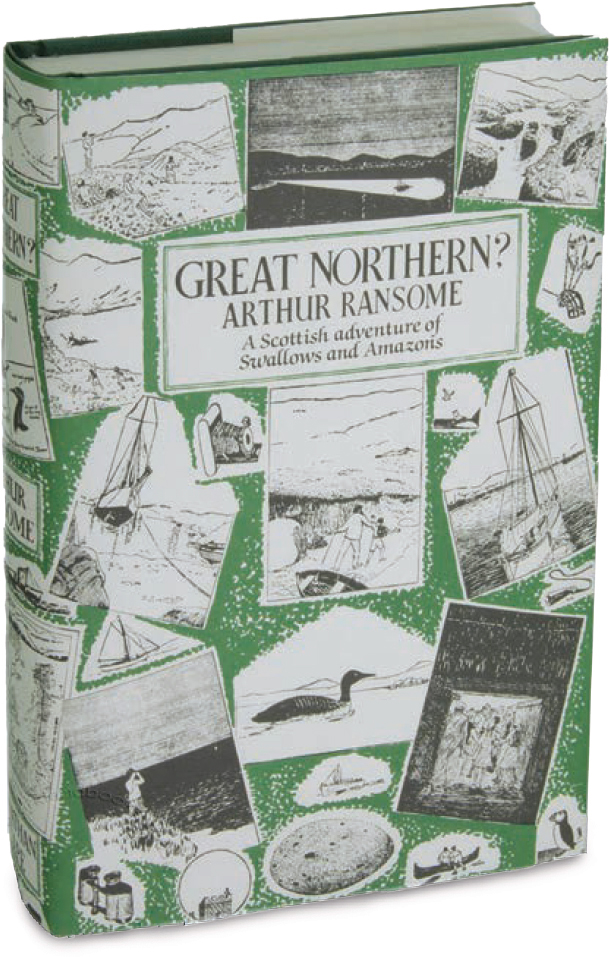

57 : Great Northern? by Arthur Ransome

1947

As birding became more widespread as a hobby, birders themselves became figures of eccentricity and caricature in the popular consciousness, subjects sometimes of ridicule, but with the pastime also portrayed as a healthy and suitable occupation for children in novels like Great Northern?.

Birds are represented comprehensively in literature. Shakespeare’s plays allegedly mention hundreds of birds, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), John Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale (1820) and many more poems contribute to the artistic mythology in the same vein. Yet such works don’t deal with the perceived need to watch and observe birds. Writers on ornithology and birding themselves are often inspired into flights of lyricism when describing birds and their habitats, perhaps most notably in The Peregrine (1967) by J A Baker.

But birders are to a degree underrepresented in the creative arts, though particularly since the Second World War their habits and rituals have begun to appear increasingly regularly in movies and in novels. Such appearances say a lot about the public perception of the hobby.

An inspiration for many a growing birder was Great Northern? by Arthur Ransome (1947), the final part of his perennially popular Swallows and Amazons series of childrens’ books. The child heroes of the series try to identify and protect a nesting diver species, against the wishes of an evil egg and specimen collector, and the black-and-white good and evil issues of the book must have stirred many an old-school conservationist into a lifelong vocation involving birds.

But birding is also represented in other narrative genres. The perceived aloofness of the hobby, often solitary and perhaps the preserve of social misfits, has lent itself well to the crime novel; since the early 1980s, authors such as J S Borthwick, Ann Cleeves, Lydia Adamson and Karen Dudley have added birding to the Agatha Christie via Henning Mankell sweep of the modern crime novel. Cris Freddi has also introduced an existential, Camus-like spin to the genre with Pelican Blood (2005), while Sally Hinchcliffe perhaps followed a similar though more original course in her poetic and hypermetaphorical Out of a Clear Sky (2009).

Few novelists appear to be genuine birders, but one who may come under that description is the US author Jonathan Franzen, a novelist beloved of Sunday supplements who has become a somewhat self-conscious public face of birding stateside, to the chagrin of some. Authors Margaret Atwood and Graeme Gibson have earned great respect as emissaries and fundraisers for Birdlife International.

Pelican Blood was less successfully adapted to the cinema, while other filmic prejudices of the hobby have been made as artistically poor comedy – step forward The Big Year (2011) – and genuinely creepy claustrophobic thriller, in the case of The Hide (2008). Aside from repeating essentially the same documentary twice in Encounters: Birders (1996) and Twitchers: A Very British Obsession (2010), the medium of television once added a surprisingly sympathetic birder to a sitcom in Watching (1987-93), a Liverpool-based light comedy which lasted seven series, though the hobby took a quite minor role after the first, mainly being used as a trope, to signify the male lead’s shyness and awkwardness.

Birding, therefore, is over-archingly artistically represented as the pastime of stalkers, murderers, deceivers and cuckolds, with only the protagonist of an Eighties sitcom approaching the more mundane reality – a far cry from Arthur Ransome’s 1947 portrayal. The motivations, excitements and passions of the hobby – in fact, the birds themselves – are still seemingly a mystery to most writers and the general public.