THE ORIGINS OF CITROËNISM

|

THE CITROËN JOURNEY began with one man, André Gustave Citroën (1878–1935). He is our hero, but he did not do it all alone, and although loyally French, he was not actually French by DNA. Citroën as a brand and as a family may well be perceived as utterly French, the widely written truth upon which we must briefly alight is that this family were Dutch and Polish in their original DNA. André was born in Paris on 5 February 1878, but his diamond dealer father Levi Bernard was of Dutch-Jewish origins and his mother Masza Amalie Kleinmann was of Polish-Jewish extraction. Today the Dutch have a special affection for Citroën, and this should not be a surprise, for André was, in part, one of their own.

The name ‘Citroën’ is said to derive from a name change that stemmed from his grandfather’s origins named as ‘Limoenman’ – literally ‘lemon man’ in Dutch. The link to citrus fruit or ‘citron’ becomes obvious, but on moving up the social ladder the family created the name ‘Citroën’. The name was initially spelt as ‘Citroen’, being devoid of the ¨ or diaeresis over the e, the addition of which creates a phonological change in sound by separating the spoken letters.

In Dutch, oe is pronounced as ‘oo’, so it is not unusual to hear a Dutch Citroën owner refer to a ‘Citroon’. The correct French pronunciation of the name is Cit-ro-ën with emphasis on the last syllable ‘ën’, therefore it is not pronounced as the English say, ‘Cit-chrun’ nor ‘Cit-rown’. Nor is it to be confused with citron in French as meaning lemon, nor is it ‘Cityoen’ meaning people or citizen.

So, ‘Cit-ro-ën’ (Si-tro-en) it is.

André Citroën was one of five children. His mother died when he was small, his father died in 1884, and his brother Bernard was killed in World War I; André was educated by relatives. After a sojourn in America as early as 1913, in 1914, young André married a Giorgina Bingen, who was of Italian extraction but a French citizen; Perhaps it was his DNA that made André who he was, a genius of future vision, seeded in French thinking and culture, yet unblinkered by not having a sole, single strand of thought or national stereotype. Tellingly, André was also fascinated by the futuristic ideas of Jules Verne.

Citroën’s tutelage began at the Lycée Concordat upon the death of both his parents before he was ten years old, and then at the Lycée Louis le Grand. Next stop was the École Polytechnique, which was the principal technical school of Paris, from which he graduated as a young engineer in 1901. By 1905, Citroën’s active brain had led to the idea to found his own engineering company. This company was ‘André Citroën et Cie’. He was soon to make a clever business move by becoming involved in the small engineering concern, the Mors car company, owned by Emile and Louis Mors.

Prior to 1904, Mors (with input into its cars by Henri Brasier) was a success, and continued to make small runs of cars up until late 1906. Mors is said to have run into trouble due to design and production faults in its cars. Liquidation of the Mors concern was demanded by its Board, but one of the Mors directors had the better idea of bringing in a dynamic new force named André Citroën to do something new with their investment circa early 1907. Citroën was close to the director in question, and through Mors, André Citroën truly entered the motor industry. This was in fact André’s second foray into automobile interests, because his first involvement with cars had been in 1905 via a commission to build a series of engines for the Sizaire-Naudin company.

The man himself – hero, genius, maverick, engineer, paradox, and the person who helped create the dawning of a global industrial design movement: ANDRÉ CITROËN.

There was a fight for Mors, and a Lyons-based company named Rochet-Schneider wanted to purchase the outfit, but Citroën and another investor got in first. Intriguingly it was the Mors factory and Mors machinery that latterly helped Citroën earn profile and profit from his wartime armaments business, both factors in his advancement towards becoming a mass-production car maker.

Another company, Le Zebre, had been small but had made basic early cars and turned in a profit from the approximate 1,000 cars it is reputed to have constructed between 1909 and 1912. Le Zebre’s engineering brains came from Jules Saloman – who would soon work for André Citroën.

A less well known tangent to the story occurred in 1912, when André Citroën worked with his old college friends André Boas and Paul Hinstin to create a company Citroën-Hinstin. Here the three friends experimented with early ideas for gears and cogs in a small factory in the Parisian suburb of Faubourg Saint-Denis; this was a stepping stone to a larger facility near the Mors factory and the Quai de Javel. Citroën’s new gear cogs were made in all sizes, and were first used in domestic appliances such as food mixers.

KNOWN PERSPECTIVES

In World War I, having been called up for military service, Citroën used his connections (via Louis Loucheur) to secure an audience high up in the French government, where he persuaded the Minister for Production to let him set up a munitions company and greatly improve national output; in doing so he laid the foundations for his car business (the Minister was Albert Thomas). The French government organized the use of 12,000sq m of land for Citroën to set up his armaments factory on the banks of the Seine, and soon the dynamic André Citroën was building and delivering vast numbers of military shells – as he had promised he would.

After World War I, in 1919 he operated as ‘André Citroën: Ingenieur-Constructeur’. By 1924 Citroën’s own business was registered as ‘Société Anonyme des Engrenages Citroën’. Therein lay the clue, as ‘engrenage’ is French for ‘cog’ – cogs as found in gear drives and transfer mechanisms. Citroën’s cog company and its ‘usine’ (factory) was turning out machined cogs and drive bezels, the essential ingredients of Citroën’s growth, and reflecting the brief Citroën-Hinstin company interlude. Some of these gear or cog drive mechanisms were twice the height of a man, as real heavyweight industrial toolings. André’s story was that he saw some wooden helical gear cogs when visiting some of his Polish relatives in Lodz, and this set him thinking to build cogs in heavy metal and alloy. So helical gear drive bezels, aero engines and the cogs and drives within them also became a Citroën speci\ality.

In the office circa 1921, André Citroën and his closest associates.

To this day, the Citroën emblem is a stylistic rendition of the chevron pattern of gear cogs.

During the war years Citroën produced armaments under military commission; 23 million shells were made at his Quai de Javel premises (later renamed in Citroën’s honour), and this armament output later created a car production-line process that was influenced by Henry Ford’s early practices, of which Citroën was aware not least through his association with Gabriel Voisin the French aero-engineer; Citroën had met Ford as early as 1912–13, and soon, Citroën was the first European to make cars this ‘Ford’ way on a production line. And the war production had allowed André to create both personal profile and fiscal security to mimic Ford’s idea.

As a parallel, another company name lies hidden in the genesis of the Citroën story, that name being Adolphe Clement. Grown from origins making bicycles and a tyre company that had moulded licence-built Dunlop tyres – or ‘pneu’ as they became known – Clement built a company that had further English connections when the firm produced ‘Gladiator’-branded motorcycles. Clement also had a part share in René Panhard and Emile Levassor’s fledgling company circa 1897. By 1903 Adolphe Clement had struck out on his own, and had formed a new company with a new name: Clement-Bayard. This company built cars, motorbikes and automobile parts for domestic and export markets.

By 1913 the company was part of the rapid expansion of French aeronautical knowledge and production through the building of aero engines. The Great War of 1914–18 saw Clement-Bayard move into munitions production, yet despite its previous experience, upon the coming of peace the company failed to return to its core business of aero-auto-mobilia. But there was a riddle in the story, for Clement-Bayard and its vital factory capacity was bought out by André Citroën. This was to become the site of the famous Levallois factory of 54 Quai Michelet, which complemented Citroën’s existing Quai de Javel factory. Citroën’s first cars from Levallois were produced in 1921, and the last on 29 February 1988, when the final 2CV from Paris was built.

In a parallel with other car makers, the expansion of military production created the factories and funding to think about post-war needs and opportunities. By 1919, Citroën – whose factory would soon employ nearly 12,000 men and women, provided his workers with food, child care and a medical centre – turned his engineering brain to the thought of cars. But these thoughts were not of some grand limousine of a ‘land-yacht’ car for the rich and powerful, at that time the only people who owned cars, but instead a car for the people.

THE PARADOX AND THE EFFECT OF ANDRÉ CITROËN

Although he wanted to do things for ordinary working people, André Citroën also lived well; he used the beautiful villa Les Abeilles at Deauville, Normandy, close to his favourite casinos, where on one occasion he won a very large amount of money. He also bought La Ferté-Vidame’s chateau and grounds near Paris, which became Citroën’s secret test track. Yet contrary to some misconceptions, André Citroën was not a property speculator nor a collector of expensive trinkets; a gambler perhaps, but he was not a playboy, in fact André was a trained engineer, a serious thinker, and a devoted husband and father. He may have been touched by the then mood of anti-semitism, but he proved his detractors wrong with his cars. As a supporter of music and art, he sponsored those less fortunate than himself. Like his cars he was, it seems, a touch paradoxical.

For André, innovation without prejudice was the key thinking. Could André Citroën, in branding terms, be framed as not just a maverick, but the first such entrepreneur? As we will see, André Citroën was a father of design, one of the creators of what we now call industrial design, and his effect even touched the development of American design and marketing. Today, few people realize how important André’s wider effect was on our everyday lives and the products we use.

Citroën’s links to, and enthusiasm for, aviation were also very significant. Not only did his engineering company supply the emerging aeronautical industry, he was embedded amongst its pioneers, and worked and socialized with them. Many of André’s engineers and designers had aviation backgrounds, and the ‘greats’ of early aviation touched André Citroën and his thinking; he was also a friend of Charles Lindbergh, and hosted Lindbergh in Paris. Perhaps most importantly, André was close to Gabriel Voisin, a friendship that would lead to the defining event of another André – Lefebvre – joining Citroën.

From such aeronautical engineering practice emerges a question for the observer, namely why are some Citroën cars large extravagant behemoths, and others small economy cars, yet ones with special ingredients? And did Citroën start as a maker of small cheap cars, and then become an exotic big-car brand? The answer is no, for after its initial cars Citroën did not make standard, ‘basic’ small cars, nor did it create conventionally engineered big cars. All André Citroën’s cars, whether large or small, were designed to be different.

The 1934 Traction Avant was a revolution, and the Deux Chevaux (or 2CV as it appears we must call it) may have been basic, but both were designs of brilliance that defied, and paradoxically even created, conventions. And therein was the quandary, the paradox, and one of the key ingredients of the uniqueness of Citroën as a total design entity and as a brand philosophy.

EARLY CITROËN CARS

The true beginning of Citroën cars began in 1918 when in a very short time, André Citroën produced his first ‘Citroën’-branded car for release in the summer of 1919. It was based on a chassis design by Jules Salomon, the engineer he had recruited from Le Zebre. In truth, that first car was quite conventional in its appearance. Citroën is reputed to have initially commissioned an engine design of large capacity from Louis Dufresne, and then the building of the car known as the Artaud-Dufresne ‘ADC’ prototype which had originally been offered to the Mors company: Dufresne later worked for a certain Gabriel Voisin.

Citroën had nearly fallen for the high-powered limousine-thinking of the era, but he side-stepped it in a change of mind. Jules Salomon and the engine designer Edmond Moyet, both ex-Le Zebre, were the other engineering brains soon to become the boffins behind André Citroën’s first car thoughts, which Georges Haardt would subsequently input as lead production manager.

At this time most cars were built as running chassis and then sent off to an independent coachbuilder who would create the design or bodywork, a process known as carrosserie – that is, a specially created or chosen body style would be designed and built by the carrosserie as coachbuilder. Many standard chassis had unique or low-volume produced special bodies. But Citroën produced the whole, clothed car ready for delivery to its new owner. In a rare sop to fashion, Citroën offered six different body styles, his factory styles.

So was born the Citroën Type A, as a fully kitted out, 4-cylinder powered, 1327cc rated car. This was the first low-cost car, which retailed at FF950 and would be offered with self-starting using an electric starter. It boasted powered lamps and a spare wheel, and it was, of course, rear-wheel drive. Of interest, the car was the first French production car to be left-hand drive – something that was not then a set specification in France or anywhere. Announced in May 1919, Citroën manufactured 400 cars in just a few months after the first delivery in July 1919; less than a year later production figures had touched 12,000 units.

HOW ANDRÉ CITROËN’S FIRST CAR WAS NOT A CITROËN |

André Citroën’s first ‘car’ was not a Citroën – it was a Mors, yet a Mors that was never produced beyond prototype stage, but yet which did actually exist.

In 1917, when Ernest Artaud, a former motorcycle rider and mechanic, who had then worked for Panhard from 1914 onwards, met a certain Gabriel Voisin, Voisin had discussed his own plans to build a car rather than his usual aeroplanes, with Artaud. Artaud had teamed up with Louis Dufresne and created a modified Panhard-based car design. Artaud and Dufresne secured the rights to this lightweight, modified car and discussed it within the crucible of French engineering concerns at Issy-les-Moulineaux, Paris. There, Gabriel Voisin took a close interest, as he was in the process of creating his car. Artaud and Dufresne also had a Monsieur Cabaillot working with them, so the car became an ‘ADC’ in its nomenclature (Cabaillot went on to race Peugeots).

Artaud and Dufresne knew that André Citroën was also experimenting with thoughts of car design, and Dufresne had shown his early car plans to Citroën for consideration as a car for the Mors company, which at that time Citroën had had an expanding control over and a record of success in reviving – notably with new, quieter and more efficient ‘Knight’-designed, sleeve-valve engines. Citroën wanted to produce a ‘people’s’ car, yet the Dufresne design was not a car for the masses – few cars were.

In 1917, André Citroën commissioned Artaud and Dufresne to build three prototypes of the single, original version – three real rolling cars to be built in the Citroën workshops. So the first car to be built by André Citroën in his own Citroën factory was an Artaud-Dufresne creation and was intended as a post-war Mors company product. In total there were four of these working completed prototypes. But Citroën decided the design was too complex, and side-stepped the car. By March 1918, Artaud and Dufresne had taken the car, with Citroën’s blessing, and offered it to Gabriel Voisin who used it as a development base.

Some degree of confusion exists over the chronology of the above car and its process as three rolling prototypes. Source references suggest that in mid-1917, André Citroën himself offered the Artaud-Dufresne design to Gabriel Voisin. At the same time, with munitions contracts soon to cease, both the Voisin company and the Citroën company were searching for a project to diversify into: there were factories and workforces to run, especially so for the more established Voisin company.

Whatever these circumstances and their exact dates, the fact is that André Citroën’s first ‘car’ was an Artuad-Dufresne-Cabaillot design that became a Citroën-funded series of prototypes built in a Citroën-owned factory, and intended as a Mors car, yet which became a Voisin. Perhaps above all, in this vignette of early Citroënism, we see once again more proof of just how close were the aviation and automobile communities of engineering graduates, and how the process of Citroën was touched by the hand of Gabriel Voisin.

With its rather rakish front and rear wings or mudguards, there was something just a little revolutionary in this small car’s appearance; but the mass-produced Citroën was a cheaper car, not a limousine nor a laundaulette. The car had a touch of Ford Model T to it, and the frontal treatment mainly had the feel of an early car, as did the windscreen and cabin design of this ‘soft’-top, convertible-roofed car. Small, easily mass-produced like no other in Europe, the Citroën Type A was a basic yet clever little thing that had steel disc wheels as opposed to wooden or metal spokes. The car’s Citroën double chevron badge was blue – not far off Ford blue, it should be noted.

The car was solid, roomy and well engineered; Citroën sold Type A cars as Parisian taxis, earning valuable income and PR for the fledgling car company: it is reputed that Citroën had financed his own taxi company to promote his cars with drivers and passengers alike. Before long London’s taxis would be Citroëns.

The Type A was not as basic as has been often been suggested. It had expensive engineering within it that signalled techniques often only associated with the later, more obviously advanced Citroëns post-1934. The Type A had a pressurized crankshaft, expensive long-life bronze bearings, and improved oil flow pattern in the cylinder head. All these meant that the engine ran more smoothly and cooler, and lasted longer. Fittings were of high quality and the car had excellent handling and steering. Citroën’s engineers put significant effort into setting the car up, even if it was ‘only’ a 1.3-litre car. Given such factors, it should be realized that Citroën’s advanced design behaviour stemmed from his first car, not just in the ‘belle epoch’ years of the mid-twentieth century: so the seeds of a specific design research culture were sown far earlier than is fashionably perceived.

Type A and 5CV cabriolet owned by Clive Hamilton Gould: although styled in the idiom of their era, a great deal of high quality engineering went into these rear-driven cars and their resultant capabilities.

In 1920, André Citroën also experimented with a half-tracked car based on the Type B that had agri-utilitarian or military possibilities. This design was known as the ‘Autochenille’ (caterpillar), and used the patented track-driven ideas of Adolphe Kégresse. In rural France and Switzerland this ‘soft-roader’, as we might term it today, sold well and built up the brand name profile of Citroën. The French army and the farmers of rural France loved the half-tracked Citroëns and their capabilities.

By 1921 André Citroën had recruited his first technical director, a Louis Guillot who had also graduated from the École des Arts le Metier and, of significance, had worked on aeronautical designs for the Morane company. It was Guillot who would also recruit Maurice Broglie from La Regie (Renault) to manage the Citroën drawing office in 1924.

For 1922, Citroën had produced his Type B with a larger 1452cc engine, and 89,841 cars were sold across five years and in a multiplicity of body styles. Then came the cars that included a two-seat sports body with a cross between boat-tailed and torpedo styling. This was the famous ‘jaune’ or yellow car, as the only paint scheme offered was a strong hue of lemon yellow, a citron Citroën! One version of the B2 car was a two-door, with stylish, elliptically shaped side windows – perhaps the first hint at a Citroënesque style. For 1925 Henri Jouffret had designed a 1579cc L-head engine for the B12/B14 cars; Citroën’s cars may also have been the first to be attractive to the emergent class of female drivers of the 1920s.

The nomenclature of early rear-wheel-drive Citroëns are framed by the French fiscal tax rating created in 1925 as a ‘Systeme des Chevaux’ originating from a chevaux vapeur, then defined as steam power; this confusingly led to a ‘CV’ as a taxable rating band that was streamed across various set ‘CV’ ratings such as 2, 3, 5, 7, and so on. However, it did not indicate the exact rated power of the engine in the English sense of brake horse power (bhp), as defined in the later Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), or the Deutsche Industrie Normalen (DIN) definitions. So a ‘5CV’ Citroën can even be called a ‘5HP’ car in the context of its CV band rating, but that is not to define it as a ‘5hp’ (bhp) car in the output-rated sense. So HP derived from CV is not hp as in bhp; a later Type A described as a ‘10HP’ was actually a ‘10CV’ and in reality had 18bhp. Such confusion perplexes observers to this day.

Similarly, the definitions of British-built Citroëns do not always agree with the French nomenclature, and this applies not just to rear-driven cars but also to the Traction Avant. Differing engine options created much confusion amongst badging.

The 5CV Type C2 of 1922 was given a longer chassis in 1923, and developed into the C3. By 1924, the Type C two-seater had grown a centrally positioned third seat just behind the front seats, giving rise to an early ‘cloverleaf’ or three-petal pattern-related Citroën name: the ‘Trefle’. The period had also seen the B2 become a Citroën ‘Caddy’, as the company’s first small sportster, of which only 226 were built; soon after, another sub-1.0-litre car emerged as the 5CV.

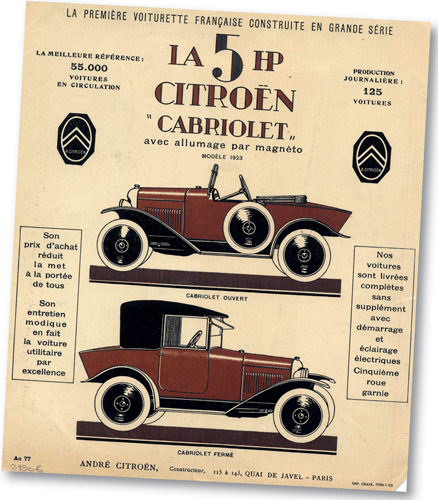

Classic French advertising for the 5HP with magneto for the 1923 model year.

Citroëns from the early period 1920–23 differed in specifications as the company developed. For example wire wheels were optionally fitted in place of steel wheels. Early Type C vehicles had coil ignitions, but later cars had magnetos; a resultant ‘old’ and ‘new’ model definition has been applied to these Type C cars. The B14 Taxi circa 1925 was a typical example of opportunistic marketing, with its upright stance, real wickerwork side panels, and large blue- and gold-painted ovaloid chevron badges mounted on each side.

By the mid-1920s, Citroën had opened up not just new factories such as the one at Levallois, but had also decided to address and re-frame the needs of the car market and its various sectors. Citroën also employed Lucien Rosengart as finance and planning director, to address his projects and marketing pitches (Rosengart put up Citroën car prices). In 1923, Citroën employed Maurice Norroy as a business executive, and recruited another engineer, a Paul Laubard. Also employed was Georges Sallot who had worked with Salomon on the B series cars.

Citroën dropped the 5CV car in August 1926 as the company moved upmarket to cars not just with larger engines, but also with steel bodies. Thus the B10 was the first fully steel bodied car in Europe (using American-supplied Budd Company pressed steel), not in a monocoque sense, but as a steel-clad coachwork. This stemmed from André Citroën studying and having discussions with the American Budd company, who made steel shells for railway carriages and supplied all-steel car bodies in the USA (André’s first visit to America was in 1912). In fact it was a Budd-licensed process that allowed Citroën to explore all-steel body construction. Citroën erected a steel-stamping or pressing plant at St Ouen-Gare, and then employed J. Paul Vavon as technical director for the newly titled ‘Société Anonyme’ that was the Citroën company.

Roof up, the car looks decidedly ‘vintage’.

Citroën also bought land and factory floor space to allow for expansion, and built a foundry at Clichy. Clearly this was a period of massive expansion under a determined personality, with some degree of a desire for self-publicity. For 1925, the B10 Type was a Citroën ‘first’ with all-round disc brakes. Then a new 9CV-rated L-type engine of 1539cc boosted the B14 model, which had shades of American styling in its looks; the engine had been designed by a Henri Joufret, another aeronautical engineer who had graduated to automobiles (via Peugeot). Citroën manufactured 50,526 B14s in 1926–27.

UPON BECOMING INDIVIDUAL

For the middle years of the decade, Citroën turned out the B12, the B14 of 1538cc and 22bhp. These, like the later B18 model, were upright and staid in their styling, aping British Edwardian ‘Landaulette’ coachbuilt shapes that the English upper classes favoured. Then came the C12/27, the C4, and leading to the first 6-cylinder powered Citroën, the 2442cc, C6 and then the C8/C12. A hint of a more modern, more defined style of Citroën design motif began to emerge in around 1929, when a slightly raked-back ovaloid grille design bearing the Citroën chevron became the first visage or graphic of Citroën.

The cars of 1929–30 also developed a sculpted, compound curve shape to the joining of the front body and windscreen pillars, but in other respects, even these larger, more contemporary Citroëns still lacked a defining essence. It was upon the front grille of the 1932 Rosalie two-door (but not on the smaller 1933 Rosalie 10L Faux Cabriolet) that the first major iteration of the chevron logo would appear as two large inverted V-angled chrome bars emblazoned across the radiator grille (this was before the Traction Avant made such a technique more obvious), and would also appear as a defining styling element on the Type 23 commercial vehicle in the early 1930s.

Good cars though the early Citroëns were, the brand Citroën had yet really to fully define itself or its image. The cars were not revolutionary, and some were basic, but Citroën was en route to the definition of its own motifs: yet could it be that the brand Citroën was André himself, and that his product was in part secondary? This would soon reverse itself with a product that defined the brand and led to further identity of product, not of name or badge.

Ever the astute marketeer, Citroën seized upon the popularity of his half-tracked cars and devised overland treks to prove the concept and raise profile during the 1920s. Citroën offered seats to scientists and journalists on a series of adventures using the half-tracks, and the ensuing PR coverage was worth millions.

From December 1922 to January 1923, a Citroën half-track expedition had crossed the Sahara Desert from Algiers to Tomboctou (Timbuktu). The Autochenille, driven by Georges Marie Haardt and Louis Audouin Dubreuil, led the first trans-Sahara crossing by car. Their 10bhp-powered B2 half tracks traversed 3,200km (1,990 miles), achieving an incredible 150km (93 miles) per day in the shifting, unmarked sand ways. From October 1924 to June 1925 another Citroën half-track expedition drove from Algeria to the southern Cape of Africa via Kenya. This was the journey so unfortunately titled the ‘Black Journey’ or ‘Croisere Noire’. Asia beckoned as late as April 1931 for a ‘Yellow’ trip – the ‘Croisere Jaune’ – starting in Beirut using C4 and C6 half-tracks. This pair made it as far as what was then Peking, via the high mountain passes of the Himalaya. At one point both Citroëns had to be dismantled and hand-portered across the impassable mountain tracks. But they were re-built and drove on to China.

Pierre Louÿs

Citroën also created an in-house PR or ‘propaganda department’ in the 1920s, and its first director was Pierre Louÿs (another graduate of the École des Beaux Arts) who oversaw a mass advertising campaign using art and poster design as an innovative marketing tool; Louys drew many of the famous adverts used by Citroën.

Pierre Louÿs had joined Citroën as a draughtsman and emergent stylist, but would become a vital figure as the firm’s first artistic director. He provided a further link to great design when he married Jeanne Morel, one of Chanel’s top designers. Louÿs’ assistant was Eugene Michel, and from 1924 Citroën had an atelier or studio for its artistic output and in-house car-body design, led by Louis Theux. André Martin was a senior figure in the project planning office.

By 1925 Citroën was a household name, not just through its cars but through André Citroën’s clever marketing, which included hiring aircraft to write his name in contrails in the sky over Paris, and fitting 200,000 light bulbs and many kilometres of electric cabling to the Tour Eiffel.

Citroën and Lalique

André Citroën was a man who played for high stakes, and in business terms often won. His marketing skills may have been extravagant, but his sponsorship activities certainly encouraged creative works.

In 1925 Citroën sponsored the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes. This major Paris exhibition led to the illumination of the Eiffel Tower in its sponsor’s colours – thousands of light bulbs that read CITROËN. At the same time, André Citroën sponsored the glass artist René Lalique, maitre-verrier, and it was with Citroën’s encouragement and sponsorship that Lalique began his creation of a series of exquisite car mascots that took the design of this device to a new relevance in automobilia. Naturally Lalique was commissioned by André Citroën to produce a stunning sculpture of five horses as ‘Cinq Chevaux’: this was applied to a 5CV Citroën. Lalique went on to create car mascots for the height of the Art Deco period to complement his previous works with Coty sponsorship.

Art Deco extravagance: aping the Lalique influence, this 1930s mascot mounted on a Traction Avant Roadster encapsulates the style of the era.

The exhibition and its exhibits of advanced design stunned the world and had a major effect upon the emergence of American industrial design.

AUSTRALIA AND AN AFFAIR WITH ‘LES ANGLAIS’

Somehow, a Citroën C-type ‘Torpedo’ found itself in Australia as early as 1925. There it was driven by a Mr Neville Westwood as a used, secondhand, high-mileage car all the way around the available roads of remote outback Australia. This proved the toughness of Citroën’s components. Preston Motors of 114–122 Franklin Street, Melbourne, Victoria, were the main Citroën agents at the time; by 1927 there was even a Citroën dealer in Adelaide. Citroëns were made in Victoria State until 1966.

This 1927 C12/24 was originally exported to Australia from Great Britain and returned in recent years. It is rust free and original. With steel wheels, wide running boards and upright style it is conventional yet has a certain stance and economy of line.

Still in regular use, this car displays its astounding condition as an original pale blue Citroën.

Well built in steel, is there something of the Ford Model T to the effect?

Of curious interest, Sneddons Motors of Brisbane, Queens -land, advertised the Traction Avant for sale in Australia as ‘the British Citroën’ and as the ‘only British car in Australia with Floating Power!’ How strange that the delusion of a Slough-built, French car being touted as ‘British’ should be foisted upon the ‘Empire’ set of the then pro-British Australian psyche.A 12-volt Traction Avant sold for £430 in 1950s Australia – a huge sum, but sheep farmers were rich, and if a Mercedes, Jaguar or ‘British’ Citroën succumbed in the outback, the car was dumped and a new one purchased.

One of the earliest exponents of Citroën in Australia and New Zealand was the New Zealander Jack Weaver, who became well known campaigning his Traction Avant faux coupé in rallies and trials in the marque’s early years ‘down under’. In 1949–50 Jack Weaver even constructed his own Traction Avant fastback in the early 1950s as a real coupé with an air of Bertoni-esque style and a shortened wheelbase. Incredibly Jack Weaver nearly gave Citroën its one and only Grand Prix reference when he entered a self-designed car with a modified Traction Avant engine and gearbox in the 1960 New Zealand Grand Prix. Sadly he failed to qualify. Weaver had used a supercharged Citroën engine taken from a British-built ‘Light Fifteen’ 4-cylinder, yet converted to deliver rear-wheel-drive power through his adapted gearbox design. With stronger bearings, pinnions and casing, and an internal redesign, Weaver’s gearbox stopped the Traction gearbox from self-destructing, and the concept was later added to restored Traction Avants.

A scene from the early days of Citroën production.

An Australian who cut her racing teeth on a Citroën in Australia was the famous 1920s female driver Jean Richmond. She drove a 5CV-rated Citroën tourer fitted with an overhead-valve conversion of the type most numerously sold by F. Crespelle; Crespelle was an orignal French tuning manufacturer who ‘improved’ power output.

Maybe it was the early Australian exposure that brought Citroën to General Motors’ (GM) attention in the late 1920s? At this time GM was seeking European investments, and would soon swallow Opel AG. Talks between André Citroën and GM were rumoured, but GM side-stepped the chance to gain a foothold in 1920s France.

Citroën began importing cars via Gaston and company at its first British base in Hammersmith/Acton in Britain in 1923 – to beat tough new import duties imposed by the British government at the time – and soon moved to a large Citroën-built factory in Slough for 1925. So Citroën and ‘les Anglais’ have had a long and enduring affair. Before 1936 a Danish Citroën factory produced cars from its own production line (latterly, Citroën produced cars in Chile, Argentina, Australia, Ireland, Romania, South Africa, Spain, Thailand, Yugoslavia, Zimbabwe, and elsewhere).

Japan

As an example of André Citroën’s global ambitions, the first representatives of the Citroën company arrived in Tokyo as early as 1921. Felix Schugs and Alfred Scellier arrived as André’s envoys to set up what became Citroën’s furthest outpost, as the Nichu-Jutsu Citroën Jidosha Kaishe or the Franco-Japan Corporation for the selling of Citroën Ltd. By 1925, Citroën had sent fifty cars (nearly all 5CV models) by ship to Japan, and Alfred Dommiec had organized the first Citroën Japan car rally by the Nippon Citroën club from Tokyo to Osaka.

An intriguing legal dispute lasting several years took place when it was discovered that a Japanese citizen, a Mr Yamanouchi, had, without prior communications with André Citroën, registered the use of the Citroën trademark name in Japan in early 1920 in what can only be called a clever and audacious move.

Citroën has nevertheless enjoyed a long relationship with Japan; it has sold many DS, GS, CX and SM in Japan, and today is a revered marque with an active Japanese owners’ club.

Across the Pacific Ocean, the Traction Avant soon found its way to pre-World War II America, and it would not be long before Citroën officially existed in America.

LUCIEN ROSENGART

Alongside these names there was a man who both influenced and worked for a period with André Citroën. This was Lucien Rosengart, a Frenchman from the east of the country. Like Citroën himself, Rosengart was a self-publicist and an engineer. It is accepted that Rosengart had some influence on André Citroën’s fledgling business, and it is reputed that he assisted the emerging Citroën company because he was invited to be a Board member of S. A. André Citroën, and worked as a financial director in about 1923. In the 1920s he was also a consultant to the Peugeot family after severing his Citroën affiliation.

In 1928, Rosengart used ex-Citroën man Jules Saloman to design and engineer a new small car: this was intended to be the first Rosengart-branded car. Yet he then took a different route, and got Saloman to re-engineer a licensed version of the Austin Seven. It was a first foray into car making, albeit one with British ancestry. Rosengart then created a front-drive car that followed Citroën’s lead. Strangely it was one part-based on a German license-built Adler car of Hans Rohr design. But in 1938 Rosengart returned to the Citroën idiom, for he took a Citroën Traction 11CV and restyled it with a special body that looked like a cross between a Citroën and a Mercedes with the addition of a new Rosengart design hallmark – a sharply angled ‘V’ frontal design that aped certain themes from the American Cord marque.

CITROËN AND ADOLPHE KÉGRESSE

Adolphe Kégresse was the pioneering figure behind the Citroën half-track type vehicles. Although French, his early engineering works included a stint in Russia building half-track expedition cars (including an early modification on a Packard, a British-originated Austin–Kégresse armoured car, and a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost half-track conversion in 1916 that was later used by Lenin) for Tsar Nicholas II. After the Russian Revolution and World War I, Kégresse returned to France, and resumed his friendships with Jacques Hinstin and André Citroën. It was the ‘Systeme Kégresse-Hinstin’ and its combination of rubber, alloys, belts and pulleys that was the key to the success of the Citroen half-tracks – being lighter, easier to make and service, and much quieter (albeit of shorter life than metal-based mechanisms).

Kégresse had patented his tracked vehicle idea as early as 1913, but he was soon to be welcomed into the Citroën fold. In a wise move André Citroën realized that Kégresse and his half-tracked vehicles would have a wide variety of money-making applications ranging from military use, across agricultural, local business, ambulance, alpine and tropical or desert needs. Military variants were sold to the armies of Poland, Belgium, The Netherlands, Spain, and to Great Britain.

Autochenille – the Citroën half-track as used on the various ‘Raids’ of the 1920s.

Kégresse’s system used metal tracks mounted in a composite device of pulleys, rubber blocks and steel pins that were driven as a tractive force from a power take-off device from the engine. The early Kégresse system vehicles featured a rear half-track mechanism that was driven from a rear-mounted differential that took its supply from a prop-shaft equipped engine. However, Kégresse and Hinstin soon modified the system, and by the mid-1920s the tractive force drive mechanism operated on the front section of the half-track, yet still configured from a front-mounted, in-line, rear-drive, prop-shaft type layout. With the front of the tack unit powered and the rear axle riding free, significant weight was saved, along with a shorter drive mechanism with fewer power losses and better traction. By 1927 Kégresse had redesigned his tracks so that a new steel belt and pulley and rubber cone system reduced the risks of the tracks coming off, and created more efficient pulleys.

Apart from the well publicized Citroën ‘Raids’, the Kégresse-equipped Citroën half-tracks were used not just by the French military and other desert-roaming adventurers (including the Alaskan Raid Croisere Blanche), but also by the famed explorer Admiral Richard E. Byrd in his 1934 Antarctic Expedition. This created further profile for brand Citroën on an international scale.

To further promote the idea, Citroën created the ‘Citracit’ (Citroën trans-African transport) concern as a sub-division to promote the range of half-tracked vehicles. The engineering that went into the range was intriguing: for example, the Citracit P6 used a 15CV 4-cylinder in-line engine of a massive 2.8ltr cubic capacity, originally a Mors-designed engine from over a decade earlier. Panhard were also involved in the later P16, which was a small armoured car to a Panhard design constructed by the Schneider et Cie company. The Citroën B and C series ranges provided the basis for the Kégresse range, and the C6 took over as the 6-cylinder based P-series range.

Kégresse Models

Uses: Tourism/commercial/agricultural/industrial/military/expeditions

Type |

Production period |

K1 |

1921–24 |

P4T |

1924–25 |

P7/T |

1925–27 |

P7B |

1927–28 |

P10 |

1928–29 |

P14 |

1926–40 |

P17 |

1929–34 |

P15N |

1928–36 |

P19 |

1929–35 |

P20 |

1936 |

P107 |

1935–40 |

Notes:

P16 as Panhard/Schneider armoured vehicle

P16 as Panhard/Schneider armoured vehicle

P21 and P112 special-build vehicle series in low numbers

P21 and P112 special-build vehicle series in low numbers

B2, P14, P17, P19 variants all saw service in the Polish Army

B2, P14, P17, P19 variants all saw service in the Polish Army

Early Citroënism: the view from the large steering wheel and open cabin.

COACHBUILT HEYDAYS: CREATIVE CARROSSERIE

Although André Citroën created whole cars as packages that were ready to drive, the fashion for adding special one-off or limited-series bodies to chassis did not leave Citroën untouched – indeed, many coachbuilders and body designers took the early cars for the basis of their creations, and André was hardly likely to complain.

Henri Labourdette and Son

Henri Labourdette was the son of a carriage maker. Henri founded his own role as a carrossier, and the first Labourdette cars were bodies built upon Panhard-Levassor chassis. Henri’s son Jean-Henri had a flair for design and an interest in early aviation. As early as 1910 he developed an interest in aerodynamics – or aerodonetics, as the science was then termed. Jean-Henri fitted rounded, smooth fronts to his cars and pointed ‘torpedo’ tails, and he created a series of swept and sculpted open bodies known as ‘skiff’ cars based on Panhard-Levassor chassis. His first Citroën body was a boat-tailed B2, in 1922.

Labourdette also worked for Farman and Voisin, so he too was a Voisiniste. In 1933 he created a streamlined body for a Renault chassis – but perhaps his company’s wildest moment was the spectacular body for the Delage DS-120 chassis. Jean- Henri Labourdette also invented and patented a unique windscreen mechanism that dispensed with the A-pillar, and wrapped and sealed the windscreen glass smoothly into the side window glass at the point where the door glass met the windscreen. He called this the ‘Vutotal’ and it was a redesign of the ‘montant de para-brise’ – a pillarless windscreen that allowed the driver to see a ‘total view’ without obstruction by the A-pillar.

A Driguet-bodied Car

Also associated with Citroën were the brothers René and Alexandre Driguet, who build bodies for Citroën and Voisin in their own carrosserie works. The Driguet-bodied Citroën B2 of 1924 had touring or ‘torpedo’-style bodywork, and a V-shaped split windscreen. This rakish car had a ‘duck’s back’, or semi boat-tailed rear and four seats, yet only two doors, access to the rear being between the front seats. Of note were the flowed or angled front wings. The car was rare at the time, and is even rarer today.

In 1931 Marcel Le Tourneur, son of Jean-Marie Le Tourneur, joined the Le Tourneur and Marchand carrosserie and brought in Carlo Delaisse as chief designer. Cars for every major French chassis builder resulted. Le Tourneur created a ‘Unic’ coupé in 1938 – and to say that it had shades of the Traction Avant 15/Six would be an understatement. The famed carrosserie of Franay built a limousine-type body on a Citroën Traction Avant 15/Six.

There was also a notable carrosserie named Mannessius. Derived from the name of the founder, Manès Lévy, who was of Latin lineage, this body design company was founded in 1919 at Levallois-Perret, Seine. It created its own all-metal body construction technique, and as early as 1925 invested in state-of-the-art metal presses using the patented Baehr techniques. Contracts from Fiat came in, as did one from André Citroën, who tasked Mannessius with building the bodies for his ‘Rosalie’ cars – which a certain Flaminio Bertoni styled long before he became famous for the DS.

The small carrosserie company of Bourgeois-Luchard had worked for Voisin and created an obliquely sliding partition that was patented; but Bourgeois-Luchard were soon to create a body of ‘coupé des dames’ style on a 5CV Citroën.

Other later Citroën ‘specials’ from external carrosserie would include the Robert de Clabot Citroën 11 CV coupé of 1937 that used a Traction Avant as a base. De Clabot added an American-style front bonnet and grille, and new side panels leading to a pointed tail and spatted rear wheels. Only the Traction’s windscreen and scuttle remained.

Figoni and a Prize-winning Citroën Design

In later years, even Guiseppe (or Joseph) Figoni, the stylist of Figoni and Falaschi and of Talbot fame, would build a special body for a Citroën. This would be a ‘shark-nosed’ variant of the Traction in its 1950s 15/Six guise. This 1952 design would win a design prize – the Prix de l’Art et de l’Industrie. But before that came Jean Andréau, Pierre-Jules Boulanger, Georges Paulin, Flaminio Bertoni, Sixten Sason, Battista ‘Pinin’ Farina (whose company latterly became known as ‘Pininfarina’, but only after fraternal merger with the family Farina firm of ‘Stablimenti Farina’), and a host of design ‘greats’ across an Art Deco Europe.

There were two famous carrosserie names that did not work either for or with Citroën at this time, yet their influence on the aerodynamics and design movements cannot be irrelevant to design or to Citroën. First was Iakov Saoutchick – or Jacob Saoutchik as he later styled himself. Saoutchik’s styling specials were ‘leading edge’ design, often assisted by input from other themes, leading to his trademark wildly curvaceous and perhaps over-chromed detailing on Delahaye and Tabot-Lago chassis. Saoutchick also created a body for a V12 Voisin-engined Bucciali.

The other important name of influence was that of Georges Paulin, the dentist turned brilliant car stylist and aerodynamicist, whose work with the Parisian carrosserier Marcel Portout would include the Embiricos Bentley streamliner, prior to his untimely death in World War II.

From de Lavaud and Eiffel, to Panhard, Penaud and Tatin

From 1870 onwards the likes of Louis Blèriot, Pierre Cayla, Henri Coanda, Gustave Eiffel, Leon Levavsseur, Emile Levassor, Otto Lilienthal, Frederick Lanchester, René Panhard, Ettiene Bunau Varilla, Alphonse Penaud, Victor Tatin, Nikolai Zhukovskii, to name some key players, had paved the way. The Hungarian-Swiss-French Paul Jaray would soon soar above many of these names with his aerodynamic car designs (these were redesigns of car bodies upon existing car chassis, as opposed to entirely newly engineered cars in total). Yet it was the French pioneers who were the first generation of aerodynamic car designers (with Tatra being owed an honourable mention), before the advances of German car design and aerodynamics of the 1930s.

Two further projects framed the technical advances: Rumpler’s Tropfen-Auto, and Auriel Persu’s sleek, aerodynamically sculpted ‘Correct Car’ concept.

Circa 1914–25 there were other names with Voisin links that would end up with Citroën links – notably the Paulin-Ratier aviation company and its engineer Paul Dreptin. The Paulin-Ratier company would soon manufacture the Citroënette, a half-scale pedal car with which André Citroën would market his brand to the minds of French children, who would, of course, grow up to buy his full-scale cars. Citroën would in the 1920s also produce so-called ‘toy’ cars in the form of the accurate tin-plate Jouets Citroën, with which he would pre-condition his future clients. Production ceased during World War II.

This Jouet Citroën model depicts an early C6 camion.

Pierre Delcourt was an aero-engineer who privately made the first aerodynamic Citroën saloon – a papier-mâché and wooden built boat-tailed affair on a C4 chassis in 1928.

Other significant early explorers of aerodynamics were Ettiene Bunau Varilla, Marcel Riffard and Gaston Grummer. Grummer would build a series of early aerodynamic car bodies, notably for Voisin. The Spaniard Jean Antem would influence Panhard design, and in the 1930s build his own design on Citroën Traction Avant underpinnings: the carrosserier Henri Esclassan would do likewise with his modified Traction Avant ‘Splendilux’.

France was at the heart of advances in structures and aerodynamics amidst an engineering explosion of ideas. But then came the 1929 economic crisis that began in America and shook the world. Just as it took hold in the early 1930s, André Citroën tore down his factory and rebuilt it to cope with ever-increasing demand, spending millions of francs in the process. He also sat down with his team and decided to create a whole new range of cars, and dreamed up a way of taking a massive leap forwards in design terms. It was a big risk, yet one that may not have been as obvious as hindsight might suggest.

As Europe’s economies faltered, so too did orders for new cars. Yet at exactly this time Citroën had launched two cars that were arguably its first real attempt at defining a true Citroën style in design terms. These cars were the Citroën 8, a small, low-slung, two-door sports-type coupé; and the large, upper-class limousine Citroën 15, as the ‘haut de gamme’ range-topper.

Moteur Flottant and a Swan

In 1932, André Citroën marked a future thought by mounting the engines of his cars independently from the chassis. Iron-to-steel mountings were eliminated for the engine block to chassis joining. Instead, a ‘floating’ rubber absorber or cushion was made to carry the engine to body linkage. This ‘moteur flottant’ reduced vibration and resonance in the chassis and body to a remarkable degree. Suddenly Citroën had developed a notable characteristic in its cars. It was in fact an American-owned, but French-created idea that Citroën used under patent license from Chrysler. The system was the brainchild of Pierre Lemaire and Paul d’Aubarède, who had sold the patent to Chrysler – but perhaps the French public did not know that!

André Citroën coined a graphic icon of a swan, serenely sailing along unruffled by its unseen paddling. It was an inspired piece of alliteration, and the swan ‘flottant’ badge was featured on the front of Citroën cars, and so equipped the revised C4G and the 2.6-litre C6G of 1932. And if the engine could be isolated from the chassis, could not the suspension? Now there was a thought for the future...

Jaeger instruments and chevron motifs amidst an elliptical instrument panel mark a proper Citroën dashboard.

Le Mans – Just

As the 1930s dawned, there came about the strange tale of how in 1932 a Citroën C4 Roadster entered by a young man named Henri de la Sayette competed at Le Mans at the Grand Prix d’Endurance. The C4’s co-driver was to be a Charles Wolf. Sadly the C4 consumed its electrics after just three laps, with Wolf at the wheel. Henri de la Sayette never got to drive a Citroën at Le Mans, and it would be decades before another Citroën attempted the race. Recently this happened in the hands of Antonia Loysen and Celia Stevens in July 2010. On that date, Loysen’s privately created 1932 Citroën C4 racer came home in forty-seventh place in the Le Mans Classic race, giving Citroën only its third Le Mans appearance in eighty-seven years2.

The second appearance was in 1972 by a privately entered SM driven by Guy Verrier. Citroën had refused Verrier permission to drive a new SM at Le Mans (not least after an SM had expired at the Spa endurance race in late 1971), but in the end Verrier’s Ligier-tuned SM did enter Le Mans. A second private entry has also been claimed for the same year.3

Citroën’s 1920s competition cars (often racing at Monthléry) carried the brand logo of the Yacco oil company whose sponsorship of Citroën competition cars continued for decades, including the 1972 SM at Le Mans.

De Lavaud’s Citroën-supported Advanced Designs

Another great early pioneer of all things aeronautical and automotive was Dimitri Sensaud de Lavaud, a Brazilian who moved to Paris in the 1920s. De Lavaud is well known for his subsequent designs for the speed-sensitive self-changing gearbox mechanism, and a patent for independent front suspension. He had made Brazil’s first powered flight in 1909, and built several prototype cars in the late 1920s, including a steam-powered device and a cast alloy mono-piece chassis in 1927. These were constructed in Paris, and André Citroën took a close interest – indeed we can speculate as to whether de Lavaud’s advanced thinking may have been part of the catalyst for André’s own thoughts. Early de Lavaud gearboxes were fitted to the prototype Traction Avant (but not for production), thus proving how close Citroën was to de Lavaud, and the importance of the obscured influence of the latter.

What is less well known is that with the Citroën company’s financial support (approved by Pierre Boulanger), de Lavaud designed and built a rotary-cycle engine in the years 1937 to 1941. The use of a diesel-fuelled rotary engine was also considered at this time by de Lavaud. This unique project was, after the Traction Avant’s front-driven ohv powertrain, a significant example of Citroën’s interest in advanced and alternative engine technology.

ROSALIE – THE LAST OF A FOUNDING LINE

In 1932 the last of the pre-fwd revolution Citroëns, the Types 8–15, and the delightful ‘Rosalie’ range, heralded the initial run of early Citroën design motifs. The ‘Rosalie’ range was inspired by a number of tuned roadsters that set endurance records using streamlined bodies of varying forms, notably the ‘Petite Rosalie 8’, a wonderful blue-painted, boat-tailed racing machine which created illustrious speed record-breaking scenes at Monthléry as late as 1933, when the car covered 300,000km (186,420 miles) in 134 days of near-continuous running at an average speed of 93km/h (58mph).

There were definite hints of late-1920s American styling to the Rosalie saloons and the decidedly Packard-esque Rosalie 15CV Coach Grand Luxe coupé of 1933, and the designation NH, or Nouvel Habbilage, was used to signal these new, larger, revised Citroëns. A key figure in the development of the Rosalie cars (and the engineering of the subsequent Traction Avant) was Jean Daninos, who joined Citroën in 1928 as a body structures specialist (Daninos went on to found FACEL).

For the rather upright Rosalie range it was the ‘CV’ rating rather than styling that set the marketing trends – people wanted more power. Citroën fettled and modified these cars, even restyling them and adding his new independent front suspension to the last 226 of the 54bhp, 2650cc, 15CV-rated variant.

A series of special streamlined bodies adorned a few of these later revised Rosalie chassis, and lightweight or ‘légère’ versions of smaller, shorter Rosalie bodies were also produced as 15CV cars with large engines but smaller bodies from the 10CV Rosalie. Confusingly there was also a 10CV Légère. A brief closing highlight for the Rosalie range was to see the car fitted with the larger overhead-valve engine from the Traction Avant in 7CV and 11CV rating. These engines had to be turned around – ‘moteur inverse’ – in order to work in the rwd configuration. The 1628cc from the Traction 7 had its capacity increased to provide a higher cruising speed.

André Citroën also allowed the use of externally designed coachbuilt special body designs on a series of late model cars. Contributing carrosserie included companies such as Sical, Manessius and Millon Guillet. It is reputed that over fifty specialist body designs were applied to Citroën Rosalie chassis up to 1937. Incredibly, in 1935 even an early diesel engine was fitted, after development by Ricardo in England. Later Rosalies were also fitted with the new torsion bar suspension designed for the Traction Avant. However, a plethora of body styles, and large modifications in parts that became model specific and not interchangeable, had since the late 1920s created a huge operating cost base: it was a symptom, and one perhaps of no surprise.

The larger Rosalie cars were the first ‘big’ Citroëns in the fashionable sense of the term, and were manufactured until late 1938 alongside the new Traction Avant until it gained wider acceptance – a wise move on the part of the Michelin directors who by this time controlled Citroën.

Soon André Citroën would go the whole way and create a car with everything that was so new, so unheard of, that it marked a new chapter in his company’s life and in car design, and finally reflected both himself and the times he loved, and those people that surrounded him. It also reflected his admiration for American practices, and his effect upon America and the consequences that created car design.

There was the matter of world economic difficulties, cash-flow interruptions, and the need to seek further investors to stay afloat. This was because the new car that Citroën would soon launch, would also fail to take off immediately – not through any fault of its design (although there were teething problems with the car), but because of the economic crisis. Buyers all but dried up for several months, and not least overseas due to exchange controls and poor fiscal rates. Citroën’s expenses in building factories, creating cars, and maintaining an international profile had been huge, running into hundreds of millions of francs: the company owed its suppliers and its bank, and a rare strike at the factory also upset the financiers.

Circa 1930, a ‘Rosalie’ leaves the Agence Citroën at Grand Garage Vienne in Brest, Finisterre, Brittany.

KEY MEMBERS OF THE DESIGN/ENGINEERING TEAM PRE-WORLD WAR II |

Flaminio Bertoni |

Pierre Louÿs |

Gustave Behr |

André Martin |

Maurice Broglie |

Paul Mages |

Charles Brull |

Pierre Mercier |

Jean Cadiou |

Eugene Michel |

Marcel Chinon |

M. Monteil |

Pierre Louis Cordier |

Edmond Moyet |

Raoul Cuinet |

Jean Muratet |

Paul d’Aubaurd |

Theo Nordinger |

Jean Daninos |

Maurice Norroy |

Alfred Dommiec |

Roger Prud’homme |

Henri Dufresne |

Pierre Provost ‘le |

Alphonse Forceau |

Colonel’ |

Pierre Franchiset |

Leon Renault |

Raphael Fortin |

Louis Robin |

Louis Guillot |

Jules Salomon |

Georges Haardt |

Georges Sallot |

Charles Houdin |

Maurice Sainturat |

Henri Jouffret |

André Sellier |

Maurice Julien |

Pierre Terrason |

M. Kazimierczak |

Louis Theux |

André Lefebvre |

J. Paul Vavon |

André Louis |

|

As the major French national corporate entity, Citroën may have been at risk of investor speculation, and the thought of a foreign investor getting their hands on a French institution must have caused concerns at the highest level. The possibility of investment in Citroën from Opel, Chrysler, Volvo and Skoda were all rumoured4. France was also in the midst of industrial and political crisis at this time, and the expensive employment laws that were imposed on major companies via the Front Populaire were not insignificant to the Citroën story.

By 1933, through various contacts and discussions, Citroën found himself selling a major share of his creation to the Michelin family concern. The Michelin family knew what Citroën was capable of, and also what waited in the wings. Nevertheless, that did not stop them pruning the number of employees at Citroën, and invoking cost-cutting measures which some have described as a ‘purge’. But had Citroën been top heavy and over-staffed?

Inside Michelin was the future Citroën luminary of Pierre-Jules Boulanger, a man with a massive brain and huge engineering/architectural/design-minded talent.What was about to happen at Citroën under Michelin had the roots of its revolution in the often ignored beginnings of Citroën, and the influences of an important age in social, artistic, cultural and engineering advancement.

Before embarking upon the Citroën journey post-1934, the genetics of its latter progeny need to be understood. We need to know what made Citroën, what created the mindset of its just-about-rational engineering extravagance – it was not just André Citroën and his interesting personality with its expansive lateral thinking. As the Citroën story evolves to 1934 and the Traction Avant, we have to go back to the roots of the Citroën tree, and dig up the deep, often hidden layers of what made Citroënism, for therein lies the often ignored DNA of the Traction Avant, the marque itself and its later ideology, even of today’s Citroën cars.

MICHELIN: DYNAMIC DYNASTY |

The Michelin family and their business based in Clemont-Ferrand were another tangent of early French industrial excellence. They were also major supporters of early aviation, and suppliers of the prestigious Michelin Trophy awards to early aeronautical pioneers; this also touched the development of British aviation through Samuel Cody, who won two Michelin awards.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century the brothers Edouard and André Michelin started a business importing rubber, and creating and manufacturing a new range of products. It was not long before the idea to produce car and aircraft tyres became obvious. During World War I Michelin built over 1,850 aircraft in its factories; by 1930 it was a household name in France, and Citroën’s supplier of tyres. When Citroën went bankrupt in 1934, Michelin was its largest creditor. Almost overnight, Michelin took the reins of Citroën, and Pierre Michelin became the guiding hand that oversaw the Traction Avant and placed Pierre-Jules Boulanger into Citroën. Sadly Pierre was killed in an accident in 1938, leaving Boulanger to master Citroën.

Michelin’s Monsieur Bibendeum mascot was a marketing icon across the decades.

In 1946 the Michelin ‘X’ tyre was developed for Citroën; it was applied to the Traction Avant and 2CV, and was used on the DS. This tyre broke new ground in terms of its construction, webbing, fibres and compounds.

Without Michelin, Citroën as a marque would have died in December 1934. In 1974 Michelin sold 50 per cent of its interest in Citroën, and when Peugeot took full control of Citroën in 1976, Michelin gained 10 per cent of Peugeot Société Anonyme shares, thus continuing an involvement with the beloved marque of Citroën.