GENESIS OF AN ETHOS

LEFEBVRE UNDER VOISIN AND BEYOND

|

LEFEBVRE UNDER VOISIN AND BEYOND |

FROM 1919 TO his death in 1935 André Citroën created the beginnings of the fantastic legend of Citroën, but it took a series of circumstances to bring together the alchemy of themes, talents and knowledge that resulted in the brew that became the magic of Citroën’s design revolution for small as well as big cars.

The essential, elemental Citroënism stemmed from just a few men. André Lefebvre was in 1933 the man of the moment for Citroën, but he had been trained and influenced before that point. Lefebvre was, after all, an aeronautical engineer, car designer, road racer and innovative genius prior to his arrival at Citroën, and he is rightly credited as the man behind the advancement of Citroën’s ethos of front-wheel drive, and the early consideration of aerodynamics, clever packaging and exquisitely intelligent engineering. From Traction Avant to the DS, Lefebvre surely became the embodiment of an identity for Citroën.

But did Lefebvre just wake up one morning and announce his Citroën design direction? Of course not, for behind Lefebvre’s thinking lay years of training, and the influence of one incredibly driven character, a man who was more than a genius, a personality of the polymath, that of Eugène Gabriel Voisin. Voisin was a man whose defining influence upon Citroën design is cited by a few but not known by many. And Lefebvre was not the only man to be trained by Voisin and to have influenced Citroën: there were others, long forgotten and rarely named.

André Citroën had been impressed by front-wheel drive in America where he had seen a front-driven, alloy V8 prototype of W. J. Muller chassis design at the Budd factory in 1931, and also the Gregoire ‘Tracta’ car, with its front-driven emphasis. Clearly, front-wheel drive was a meeting of minds for the two Andrés.

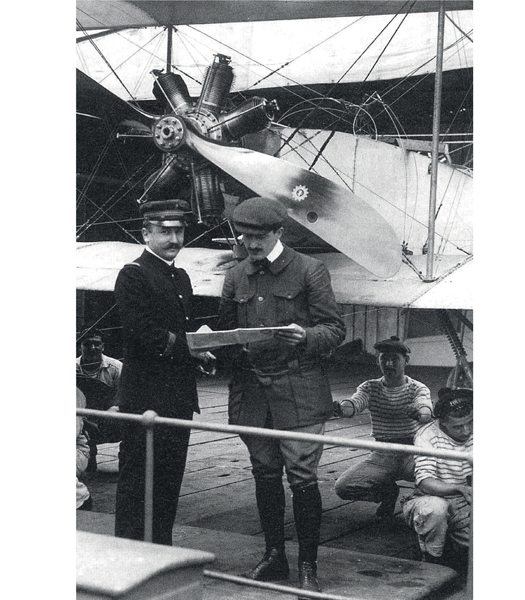

FROM BOATS TO WHEELED SKIFFS

How did Lefebvre get to Citroën? The answer is that he started out as a young engineer with Gabriel Voisin’s aeroplane company in Paris just after World War I. It was here, working for an aviation manufacturer, that Lefebvre was trained and conditioned into the thinking of aeronautical engineering standards and into aerodynamics and handling. Lefebvre worked on the design of the Voisin bomber in 1919, so his thinking, his own design research psychology, began when the evolving art of aerodynamics was born from hydrodynamics: the beginnings of aerodynamic flow studies lay in boats and their flow dynamics, and many of the early proponents of car design reached back into boat hull or yacht research for their stepping stones into creating early aviation.

Streamed Lines

The new term for smooth design was soon to be ‘streamlining’, and it would reach its peak of public perception in the 1930s when Art Deco and its ability to transform the mundane into the elegant via reshaping or reskinning became not just a fashion but a design language. But what was ‘streamlining’? It was a term that was conceived to describe the path that molecules or particles of air followed as they flowed over or from an object, so it was a line or track that they streamed along from a trigger or reference point so the air particles followed a streaming line – a streamline. The terminology stemmed from the early studies of water and fluid flows or hydrodynamics in the period 1875 to 1920.

The nautical influence was evident in terms such as ‘skiff’ and ‘torpedo’, which were applied to early attempts at automotive streamlining from about 1905 to 1925. So sailing, yachting and then sail planing (gliding) and motor-powered boating led to powered flight and onwards to car design. If an engineer knew about an aeroplane’s centre of gravity, its centre of aerodynamic pressure and its lift pattern, not to mention longitudinal stability and undercarriage suspension issues, then these things were an essential precursor to knowing the same things about a car – principally a Voisin/Lefebvre racing car, and ultimately a Citroën saloon car. Lefebvre is reputed even to have made an attempt at starting his own aeronautical company.

The fact that there was an aeronautical engineer behind Citroën’s design lineage and research psychology is of great note in the Citroën story. Both André Citroën and André Lefebvre were close to Gabriel Voisin and his aero-auto-mechanical output and influence.

A Beginning and the ‘Sup’aéro’

Voisin’s later pupil and Citroën’s future star Lefebvre was born in August 1894, of a well-to-do family. By the age of twenty-two he was an early graduate of the École Nationale Supérieure de l’Aeronautique et de Construction Mecanique (the ‘Sup’aéro’) at the highlight of French design growth, and mirrored in output by the Grand École Polytechnique.

In April 1931, after many years working with Gabriel Voisin, André Lefebvre had accepted the security of an offer to join Louis Renault to develop the ‘Reinastella’ model. Lefebvre spent two years at Renault, and reputedly there were rows with Louis Renault who had no interest in new technology: the ‘mindset’ was different, and Lefebvre was keen to move on.

Lefebvre was still a close friend of Voisin, and expressed his feelings to him. Coincidentally, Voisin was talking to André Citroën about the future of the Voisin company – but Lefebvre, the brilliant mind that Citroën required, was working at Renault. Within days Voisin had told Citroën that the man he needed to advance his engineering was Lefebvre, now at Renault. Strings were quickly pulled, and Lefebvre left Renault’s employment at Billancourt near Paris and by March 1933, within weeks, he had joined Citroën.

Born near Paris in 1894, few men have influenced not just French automotive design, but also international engineering as much as André Lefebvre. His initial studies were into early dirigibles or hot air ballons, and this led to a fascination for all things aeronautical; from this stemmed his growth under Voisin, and his vital role in the creation of the ethos of Citroën. He was the passionate visionary of the Traction Avant, the 2CV, DS, and more.

Under Voisin as his chief engineer, Lefebvre created grand prix cars and racers, and established the principles that touched not just Citroën, but later car design on the road and on the circuit. So advanced was the Lefebvre-Voisin C6 Laboratoire wood and aluminium monocoque, composite-constructed aerofoil-shaped racer, that the authorities reacted against it. Others such as Jaray and Rumpler may have created early aerodynamic cars, but they built tall and large re-creations on exisiting chassis. Only Lefebvre at Voisin investigated the low-built, low c.g, small cross-sectional area thinking that was the true advance of such work in the 1920s.

At Voisin, Lefebvre was working on large, high-powered, front-wheel-drive cars, but the idea failed – only to reappear as part of Citroën’s Traction Avant of 1934. Citroën was defined as such until the 2CV and DS, both of Lefebvre, challenged that definition. Yet the Traction Avant was a car years ahead of its time, as the DS also later became. Few other designers can claim such a record of this kind of astounding future vision and engineering capability. The Traction Avant was a seminal moment in automotive history, and Lefebvre was its father – and the DS, however advanced, was in its wake.

Lefebvre is said to have been constantly driven, a man who poured out thousands of ideas, some of which were too much even for Citroën. Perhaps other engineers were ordered by Pierre-Jules Boulanger to rein in Lefebvre’s creations a touch, but the facts are that Lefebvre never stopped. In the mid-1930s after the success of the Traction he was working long hours to create a new derivation of his ideas. These included a CVT transmission, on which he worked for over two decades before it was perfected by Van Doorne/DAF; there was a Lefebvre-conceived electrically powered car; and before that, and of great note in 1936, a small transversely mounted 1000cc engine with its gearbox mounted in situ, again an idea that pre-dated others – significantly the Issigonis use of such a layout two decades later in the Mini. Lefebvre also considered the use of a radial engine, and a de Lavaud rotary cycle in a car in the 1930s.

André Lefebvre, genius, visionary engineer and designer, and one of the greatest, yet most obscured names in European car design.

From aircraft to cars, and even to furniture and the advanced use of early plastics technology, Lefebvre can only be described as a total genius, a polymath engineer with a calculating brain, yet one with artistic flair and the capability to see beyond the dangerous, rigid, entrenched thinking of perceived wisdom and all its blinkered orthodoxy.

André Lefebvre, whose story is enmeshed in the narrative of this book, lived life at Citroën to the full. His home in the Department Var was where the DS was secretly tested. Lefebvre’s Coccinelle design project, although unrealized, was a true future vision before and beyond the DS, one that may yet define the future of rational, eco-relevant car design. His life was wonderfully celebrated in a book by Gisbert-Paul Berk5.

André Lefebvre’s time at Citroën’s Bureaux d’ Etudes remains a defining moment in automotive history. And if ever there was a spirit of Citroënism, then Lefebvre was the genie who blended the essential elements into an alchemy of automotive passion.

Timeline of Lefebvre’s Innovative Design Research Thinking

1916: Early interest in architecture and hot air balloons is manifested as design work on brakes and suspension components for Avions Voisin bomber.

1919: Assists Voisin to improve the efficiency of Voisin’s Knight-derived sleeve-valve engine; begins early research into aerodynamics and structures.

1923–24: Designs Voisin’s C6, C8, C9, C10 grand prix racing cars. Drives and competes in numerous races and trials events. Hones aerodynamics and drivetrain dynamics research; creates forward bias braking ideas. Develops low c.g. design concepts with Voisin. Researches centre of aerodynamic pressure effects and in-board roll centres and c.g. tuning; begins to develop low frontal area design thinking.

1925–29: Designs Voisin 4-cylinder and 8-cylinder world speed/endurance record-braking cars. Leads ‘Laboratoire’ car thinking, and conducts experiments into all aspects of car design. Wins the Monte Carlo rally in 1927. Designs and constructs nearly all components in the Voisin 12-cylinder V12 record-breaking car of 30,000km (18,640 miles) over ten days at an average speed of 133.53km/h (82.98mph). Works on Voisin-funded front-wheel-drive car. Innovates use of the aviation material duralumin in car design.

1932–33: Brief spell as designer/engineer with Louis Renault, and develops the 4CV Reinstella range. Renault rejects Lefebvre’s idea for a small front-wheel-drive car.

1933–34: Joins André Citroën; goes on to create the advanced Traction Avant in a matter of months – innovates the monocoque construction body; creates subsequent Traction Avant variants.

1936: Investigates radial engine design concepts, and suggests its use in a small car of approximately 1.0ltr capacity. Devises forward underslung clutch gearbox theory for transverse in-line engines.

1938: Draws up CVT transmission theories.

1939: TUB design van proposal, and early TPV–2CV concepts.

1940–45: Experiments with alternative fuels and electric car designs. Creates 2CV-derived agricultural vehicles and implements.

1946: Design work on H van, and rekindles 2CV with Bertoni.

1948–55: Explores VGD large car design concepts, culminating in the DS. Researches plastic, nylon, synthetic composite technologies.

1958: Creates advanced aerodynamic Coccinelle eco-car of great efficiency using plastics technology; designs furniture using plastics.

Given that Lefebvre had been one of the brains behind some of the Voisin company’s list of aeronautical and automotive patents, the advanced thinking that soon became manifest at Citroën should not be seen as an ‘overnight’ revelation: it had been decades in the brewing under development at the Voisin company’s Issy-les-Moulineaux laboratory in Paris.

Lefebvre was a keen car racer, driving Voisin’s ever-larger cars in races, and was best known for his stints at the wheel of the Voisin C6, a car known as the ‘Laboratoire’ for the simple reason that it sported aerodynamic fairings, a pre-Kamm, pointed torpedo tail and some clever ‘lightweight’ – ‘légère’ or ‘leggerra’ – construction techniques. Lefebvre also worked on Voisin’s record-breaking speed trials cars, and through to the Voisin C12. The pair also studied handling, as well as the effects of low-speed aerodynamics and lightweight chassis-less design. Henri Rougier was a lead driver for Voisin, and a man with aeronautical experience, and he was key to the development of Voisin and Lefebvre’s ideas on the race track. It was Rougier who won the first Monte Carlo rally. And Lefebvre had, of course, worked on a Voisin front-wheel-drive engine.

ART DECO DESIGN – BEFORE AND AFTER

From the developments of the early aero-auto era before World War I came the cultural steps that led to an ‘industrial’ practice of art and engineering: this became industrial design as an entity. Art Deco was more than just a passing moment, because it taught designers and consumers about design and the language of design by turning normal everyday items into exquisite forms and shapes, yet which retained their function. From Art Deco came a new age of design and industrial and product design, as well as building design. Car design as product design was a vital activating component in the wider history of design, yet is often ignored by some Art Deco specialists. French design and Citroën design were an essential cog in this greater mechanism.

The ‘Aerodyne’ Era

In these early years of the nineteenth century, other names would populate the Parisian design enclave which was so vital to the creation of the knowledge that became the DNA of Citroën. For instance, the English-born, but French-speaking and Paris-based Henri Farman would emerge as an aeroplane maker. By 1908 Farman was the first man in the world to fly a closed 1km circuit – and he did it in a Voisin-engineered aircraft. He also flew in America and created an aerodynamic car body design. Also in 1910, the esoteric French engineer Robert Esnault-Peltrie created a part-metal, streamlined monoplane. Like André Citroën, Esnault-Peltrie was a fan of Jules Verne, and he would also be a pioneer of rocket research, also the study of space travel, and the use of nuclear power – all before 1925.

In 1911, streamlining was taken a step further by the shape of the Tatin-Paulhan-designed ‘Aero Torpille’, or Torpedo. By 1913, the world’s first monocoque, aerodynamically streamlined wooden monoplane would emerge, not in Britain, nor in Germany, but in France as Deperdussin’s ‘Monocoque’, a truly revolutionary, high speed device that would later influence Lefebvre’s automotive thinking. In 1910 Armand Jean Auguste Deperdussin had employed Louis Becherau to create an advanced monocoque monoplane. The Deperdussin had a Swiss-French engineer as its father in Monsieur Ruchonnet. Little did Deperdussin know that his early craft with its single self-supporting ‘mono-coque’ (one-shell) body would soon influence a car – the Citroën.

FROM MONCOQUE TO POD, AND COANDA’S TAILPIECE

Levasseur’s ‘Monobloc’, Bechereau’s monocoque Deperdussin, and other French designs such as the single pod ‘one-box’ car of Emile Claveau, were decades ahead – and although this lead would be smothered by the industrial might of conventional practice, the French nevertheless had a lead that found itself expressed in cars.

Henri Coanda is remembered for his jet-type engine designs of 1910, but he, too, was a car enthusiast, and he brought aerodynamics knowledge from aviation to car design as early as 1911. Having learned about the importance of streamlining at the front of a fuselage or body, Coanda had also studied very early smoke and tuft testing techniques and early wind-tunnel findings, and realized that the manner in which airflow leaves the rear end of a car is a vital and important technique in overall drag reduction. In the early days of car design the phenomenon of this rear end wake drag was confusingly cited as a form of ‘cavitation’.

Coanda realized that upright, perpendicular rear body designs to cars were leaving a large, low pressure drag envelope, or wake, trailing behind the car. This was often exacerbated by having panels that had no defined airflow separation point. This lack of a separation point meant that the air would ‘break’ inconsistently, and its trailing vortices would be uncontrolled and both dirt-, drag- and lift-inducing. By adding a defined point of airflow separation, Coanda created a tuned and set separation characteristic and known drag and lift values.

In his remarkably prescient Torpille, as a faired-in torpedo-tailed car design of 1911, Coanda took the torpedo tail design concept one step further by placing the spare wheel horizontally in a specially shaped fairing near the base of the curved tail section of the car, as a horizontal airflow separation point or de facto ‘slicer’ ridge. The French called it an ‘aileron’, and it worked as air cleaved off the Torpille’s domed roof and stern.

Elliptical Excellence

Although the Swiss-German Wunibald Kamm is credited through his 1930s and 1950s work with defining the rear airflow separation design technology used by car makers since the 1960s, we can look to Coanda as another of the aeronauts of Paris who circa 1910 made the first explorations into a design technique that ultimately led to the teardrop school of design that made the car a singular, blended one-piece sculpture – or at least, certain cars.

In Britain, Frederick Lanchester was pioneering British elliptical studies, and as early as 1894 he had built elliptically winged craft with lower induced drag and better glide ratios: Lanchester went on to publish his results and create a car company. Ludwig Prandtl and Hugo Junkers also explored the ellipse, and in London, ‘one off’ aerodynamic car body study had also been built by Oliver North as the North-Lucas Radial (NLR). North had visited the epicentre of aeronautical and automotive convergence at Issy-les-Moulineaux, Paris (home of Avions Voisin) and been inspired into the aero-auto thinking.

Key to these early streamliners, and the later works of Lefebvre and Gerin, was the shape, form and beneficial aerodynamic (and structural) qualities of the ellipse. By 1927–28, advanced cars, and advanced aircraft such as R. J. Mitchell’s Supermarine S.5, the Short Bristow Crusader, and Giovanni Pegna’s PC.7 racing float planes for the Schneider Trophy races, were setting a trend for ellipsoid aerodynamic styling. The 1936 Supermarine Spitfire’s unique, asymmetric, conjoined double-ellipse-formed wing with incredibly low drag was shaped by the Canadian Beverley Shenstone and bore no link to previous symmetrical single ellipse wings such as those seen in the Heinkel output. The French soon turned out a Dewotine with their own version of the Spitfire wing.

Of intriguing Anglo-French relevance, Nigel Gresley’s A4 class 203.4km/h (126.4mph) ellipsoid streamliner steam locomotive that shattered the world speed record took direct inspiration from the cars of Bugatti and Voisin which Gresley studied closely, notably the wedge-fronted ‘Laboratoire’ cars.

DATELINE 1925: FROM CITROËN TO BEL GEDDES |

In 1925 the city of Paris staged a massive and lavish design exhibition entitled Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes; this exhibition spurred American design into life. André Citroën was a major force and the principal sponsor behind this important event, where the French displayed their innovative intellectual designs, created with free thinking. The exhibits stunned the world, and leading designers and engineers travelled to Paris, including American practitioners and manufacturers.

The Paris exhibition of 1925 was a turning point in global design. Those who attended it rushed home with tales of seeing a new ‘product design’ look and a new functionality, as well as the Art Deco fixtures and fittings that had been exhibited. Paris 1925 was a wake-up call to the world’s designers. By the early 1930s, some American designers had also embraced this new thinking and developed their origination of ‘industrial’ design. Through aviation, architecture and Art Deco, the car was becoming an art form.

One designer stood tall amongst the others: Norman Bel Geddes, an ex-advertising creative who had become a theatrical set designer; he was also trained as an architect. In the late 1920s Bel Geddes started turning out elliptical, podded monocoque vehicle designs with highly aerodynamic or hydrodynamic anthropomorphic shapes, some of which were taken up by the Graham Paige concern. His car designs were cab-forward, and tear-dropped with curved turrets and sloping tails that were very similar to Bertoni’s ideas. Almost overnight, Bel Geddes became one of the new industrial designers who stemmed from the need to advertise the new era of products.

From his own beginnings, the pioneering Norman Bel Geddes had adapted his early avant-garde designs from the innovations he had seen in France where the revolution in design had inspired him. Of significance, he had made a special study of French design in all its forms, ranging from interiors, to J. Corot’s paintings, to the dirigibles of H. Fressyinet, and the architecture of Rheims Cathederal.

Raymond Loewy, the Frenchman in America, became well profiled, as did Walter Dorwin Teague, Henry Dreyfuss (an apprentice of Bel Geddes), Harley Earl and others – but Norman Bel Geddes was the first futurist and of massive social influence. These other designers were the first true industrial designers of America, and it is of significance that the drive to create industrial design in America is linked directly to the great French design exhibition of 1925, which had made the Americans wake up to design.

The blend of men and their ideas resulted in a new, American design quality, as did the design of the 1935 Lincoln-Zephyr aerodynamically shaped car, as derived from the Briggs streamliner penned by the Dutchman, Johan Tjaarda van Starenborgh. The Tjaarda-shaped Lincoln Zephyr, with input from Citroën-owning designer Eugene Gregoire, was an early US attempt at an aerodyne-type car amid the early dawning of the Harley Earl GM influence of applied curves and chrome – the Chrysler Airflow notwithstanding.

The effect of the French design revolution on America’s emergent first designers is a little known tangent of the story of design itself. The birth of industrial design and of aerodynamic car styling in America has proven links from French innovations and advances in design, and principally the effects of the 1925 Paris exhibition, an event which would not have happened without André Citroën. André had already adopted American production practices, and was fully aware of the new pace of design development in America that had resulted from the 1925 Paris exhibition. This knowledge spurred him on to create something so advanced that it would wipe out even the ever-rising threat of the new American competition: the design he had in mind was the Traction Avant.

The significance of Citroën’s often ignored early history is once again evidenced as being vital not just to a later Citroën ethos, but to global design itself.

The late 1930s riot of streamlining would surely never have been born without Citroën, Voisin, Lefebvre and the 1925 Paris design exhibition (opposite). From boats to aircraft to car design, the ellipse, with all its drag-reducing, wake-tuning advantages, soon translated itself into the goutte d’eau (drop of water) school of ‘teardrop’ car design – and never more so than in the 1930s streamliner cars and the Citroëns that followed, notably the DS and Lefebvre’s Coccinelle.

Any observer in any doubt of such effects at the time of these developments only had to stand in Paris and look up at the elliptically shaped and structured Eiffel Tower, looming over them all with its grand parabolic arrogance. And the first wind tunnel in France was built by André Citroën’s friend, Gustave Eiffel, underneath the Eiffel Tower in 1912, where it provided early access to technology never before known, and well in advance of others.

The Crucial Difference

The point about André Citroën and his ‘dream team’ was that few of the mainstream industrial designers did what Voisin, Lefebvre and Citroën did. Whilst others tweaked or modified existing themes, or made exotic cars for the rich, Voisin, Lefebvre and then Citroën created entire engineering themes – new innovations as whole new cars, not just restyles on old chassis. In such types of innovation lies the subtle yet vital overarching importance of the Voisinistes and their subsequent Citroënism.

Jaray, or any other thinker, could clothe an existing car or concept in a wind-cheating body, but the likes of Lefebvre at Voisin and Citroën did more than reclothe existing chassis: they created the whole car as a new, single entity that encompassed not just aerodynamic innovation, but structural, suspension, and engine innovation too. This was the crucial difference, with the new car concept as a whole process, not just as an applied engineering tweak to cheat the wind. And it may be conjectured that Jacques Jean-Marie Jules Gerin was the ‘missing link’ between the first and second generation of aerodynamic car design movements: Gerin proponent and author D. R. A. Winstone provides us with compelling evidence that Gerin and his elliptical monocoque Aerodyne car of the mid-1920s was just that6.

Like Voisin, Cayla, Gerin, and so many others, André Lefebvre and André Citroën were, by fate of birth and era, cast deep into the thinking of these years and these events. Therein lie the strands of design ethos, the attention to advanced and complex engineering detail and to aerodynamics, that later became the essence of Citroën. Gabriel Voisin and his aeronautical influence upon Lefebvre and Citroën was significant, but there were other aeronautically influenced engineers at Citroën. Louis Guillot as Citroën’s technical guru had started his career with the Morane brothers – aeroplane builders; Henri Jouffret, the Citroën engine designer, had created a 16-cylinder aero-engine for Peugeot; and Citroën’s Henri Dufresne was chief engineer at Martini before working at Citroën.

Thus many of Citroën’s men were steeped in aeronautical engineering through their high education and early junior career roles with the French aeronautical movement circa 1910–20.

The Influence of the École

The École des Arts le Mëtiers, the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, the École des Beaux Arts, the École Grande Polytechnique, and the École Nationale Suprieure de l’Aeronautique et de Construction Mecanique (Sup’aéro) were the key institutions that trained many of Citroën’s men. It was the high engineering standards of French education, and the thinking and forensic tolerances of the aeronautical engineering mindset that drove the advanced thinking of the time and place – leading to advanced automotive ideas. In the halls of these ‘Beaux Arts’ educational centres, and in the aeronautical firms they fed with talent, is where the ethos of Citroën was seeded.

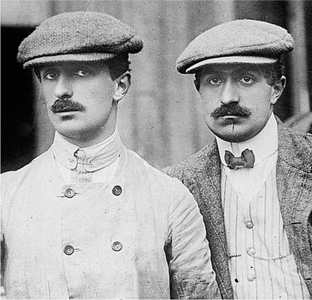

The Voisin brothers; Gabriel (left) carved a huge niche in the annals of early aviation and automotive engineering.

EUGÈNE GABRIEL VOISIN – VISIONARY GENIUS AND CITROËN INFLUENCE

No study of the origins of Citroën should avoid a detailed review of the work of Gabriel Voisin (1880–1973), who it is said was a man who never worried about how previous thinking had solved problems because he was unconstrained by the blinkers of received wisdom. This led to his free thought, his fresh innovative thinking of great originality.

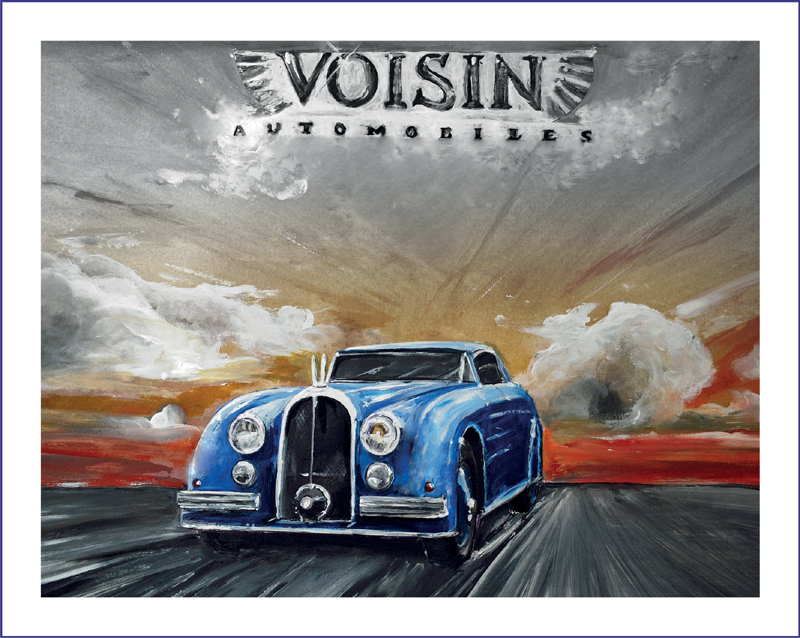

In 2011, Peter Mullin’s Voisin C25 Aerodyne was the ‘Best in Show’ at the Pebble Beach Concours in California. In 2012, the Mullin museum celebrated Voisin design in a grand ‘one-off’ exhibition. Having invested millions in his vital foundation, Mullin, like others, has become fascinated with the style and genius of Voisin, and the cascade of effects that stemmed therefrom. Even to those like Mullin and his devotees who today are ‘in the know’ about Voisin’s cars, the C25 stuns them with its amazing blend of style and engineering.

And perhaps the even rarer, less well known Voisin ‘Aiglée’ coupé C28 Aerosport, and its one-piece, sculpted ellipsoid body, was more influential than the C25. And the effect of the C30 – a last grand-coupé saloon product of the Voisin brand (by this time the Garabeddian-Voisin) – might have been far reaching, as this car had elements of later Citroëns within it, notably the DS’s clad or flocked structural frame technique.

The Voisin C25 was a very large car, yet few realize that the Citroën 2CV would appear to resemble it slightly, in a shrunken form. The Voisin C25 has a kinked ‘A’ pillar; it also has a secondary front bonnet line that dives down from the windscreen between the front wings, and extends the nose line in a manner reflected by the 2CV. At the rear, podded rear wings and a ‘C’ pillar and roof shape of incredible similarity to the original, ‘four-light’ 2CV are very obvious. But the C25 came first – over five years before Boulanger, Lefebvre and Bertoni created the 2CV.

Seen beside each other, it is clear that the 2CV looks like a C25 that shrank in the wash – the key styling elements of both cars are graphically close in all except dimensions. In fact the prototype 2CV is more organic, more curved, and features a stunning ‘hip’ joint between the bonnet and windscreen junction, one that was lost in Bertoni’s 1947 restyle. The 2CV has a roll-back roof, just like the Voisin C25. Did the C25 take any styling hints from the Voisin–Le Corbusier small car project circa 1931, which itself may have influenced the later 2CV’s own shape?

Few Citroënistes have been prepared to voice such apparent heresy, but dispassionate observation can only lead to noting the extraordinary close relationship between the shape of the Voisin C25 and the smaller, later Citroën 2CV. Gabriel Voisin it seems is an often forgotten and sometimes maligned figure of Citroën influence, unless Bertoni or Lefebvre secretly influenced the shapes of the C25 or the Le Corbusier small car proposal. Therein lies an unsolved riddle.

AERO-AUTO-MARINE

After the early aerodynamics experiments of the likes of the French-American Octave Chanute (1832–1910), in the years 1905 to 1910 the French raced ahead. With the exception of a few notables, not least the aforementioned Frederick Lanchester, the British remained in a torpor of conceit, failing to achieve powered flight, to the point where the British press attacked the sloth of British aviation, despite its vast library and its heroes of research. Indeed, it was in a Voisin aeroplane that an English -man, J. T. Moore-Brabazon, made the first piloted powered flight by an English subject, on 1 December 1908.

Meanwhile the French – and notably Ferdinand Ferber, the early French exponent of the hang glider, the car fanatic Levassor, and the separate, streamlining Levavasseur, with Louis Blèriot and Gabriel Voisin – were all racing ahead, ultimately to create the monoplane. So the cauldron of design began to bubble.

Any reader in doubt of, or sceptical about, the importance of Voisin, is asked to consider the fact that so advanced was French aviation and Voisin in particular, that on 15 March 1911, the British Bristol Company, purveyors of aircraft (and decades later, cars), signed a contract with Gabriel Voisin to employ him as a ‘consultant expert’ on the development of their first monoplane. The British had to resort to asking a ‘foreigner’ for help. Even Rolls-Royce sent a delegation to see Voisin’s V12 engine work after Mr Minchin, Rolls-Royce’s Parisian agent, noticed Voisin’s work.

Voisin evolved in the Paris-based centre of learning, as did latterly his pupil Lefebvre, not to mention Gerin and the older, ex-naval officer Cayla. This was the hub of the revolution in aeronautical design that soon embraced Citroën in car design. Paris and the years 1905 to 1920 were the key to what Citroën cars became in design: advanced, and utterly daring.

From Architecture to Automotive

As a student Gabriel Voisin had studied architecture (as did Lefebvre, Bertoni, Boulanger), and had trained with the architectural office of Godefroy et Freynet before he switched passions to engineering. He then founded an aircraft com -pany that defined design evolution, and had produced fifty-nine aircraft by 1911. Then in 1917 Voisin turned to cars, and persued his obsession with automobilia up until the 1960s.

From tracked vehicles, a 1929 front-drive transmission, a fully sliding roof section, an electromagnetic gearbox and clutch, and self-limiting brakes: these and dozens of other ideas were Gabriel Voisin’s patents between 1908 to 1966. And it was Voisin, with Lefebvre at his side, who investigated front-wheel drive and an idea for an aluminium panelled body without a frame (which itself mirrored the ‘De Vizcaye’ registered system of self-supporting alloy panelwork), and Voisin who also came up with a version of the Franco-American ‘Weyman’ body construction techniques of Charles Terres Weyman.

Voisin called his aeroplane company Avions G. Voisin, but the subtitle said it all: ‘Aéronautique–Automobile–Mécanique’ – and Automobiles G. Voisin would not be long in coming. Prior to yet another, ultimate reincarnation in Paris, the various Voisin companies led turbulent commercial lives yet were packed with advanced thinking.

ENGINEER EXTRAORDINAIRE

Voisin’s three areas of design thinking – drivetrain, structure and aerodynamics – were his passion. He occupied similar engineering ground to his friend, Ettore Bugatti, but went his own way, writing his own script of modernist industrial design (Jean Bugatti included). From incredible aircraft to cars that included the ‘Aerodyne’, the ‘Aerosport’ as Art Deco land yacht cars, and through to the 1960s with post-2CV-esque ideas such as his ‘Biscooter’ economy car for the masses, Voisin left a legacy that was not reflected by the small number of cars he made.

Voisin’s early 1920s cars were upright and elegant with a hint of both American and English styling known as ‘razor-edged’. However, this style would soon be superseded by Voisin’s growing passion for sleek torpedo shapes. Engine design excellence at Voisin came from Marius Bernard who had trained at Panhard and joined the Voisin company in 1918; he had also latterly worked at Lancia before returning to the French fold. Fernand Viallet and André Lefebvre were the next names to make their mark upon what would become Voisin’s crucible of advanced design excellence, though it was to have ‘money’ troubles (and even transfer briefly in the early 1930s to a short period of Dutch-Belgian ownership). Inside Voisin’s company were René Panhard’s ‘Systeme Panhard’ engineers, men who would later work for Citroën.

Some have questioned Voisin’s claims, but surely they cannot deny his advanced, forensic, exquisite engineering thinking – be it his, or that of his colleagues.

The Voisin-Cayla Hydraulic Braking System

Voisin and Lefebvre promoted an early form of differential or ‘almost’ anti-skid braking that was regulated by the pre-setting of the brake bias. But it was the ex-French Navy engineering officer Voisin director Pierre A. F. Cayla who created a self-adjusting, hydraulically driven braking regulator for each wheel of a car; this idea, in its ultimate modern-day incarnation via the Dunlop ‘Maxarat’ anti-skid system for aircraft, evolved into today’s ABS systems.

This hydraulically actuated and self-setting braking system was patented by Cayla, the man from southern Brittany, and it was Cayla who really conceived the idea of having individually ‘driven’ brake pumps at each wheel. In Cayla’s braking system every wheel had a closed circuit hydraulic pump driven and ratified by its own speed, and a self-limiting valve. Key to the system was an oil reservoir with a pump actuation using a delivery pipe with a by-pass return route via a suction orifice that could be set to open or closed ratings by the driver. This system received US Patent No. 1,548,349 on 4 August 19257.

As mentioned above, this system incorporated the beginnings of the famed ABS or ‘Anti-Blocker-System’, and perhaps led Citroën to the totality of its hydro-pneumatic system. Thus Pierre Cayla and his Voisin-funded system incorporated the genesis not just of ABS, but also of Citroën’s integrated braking, steering, suspension design of oleo-pneumaticism latterly developed from 1944 by Citroën and brought to fruition by three men: Mages, Maignan and Dascotte.

Pierre Cayla (left) was the now forgotten pilot, engineer and inventor who worked with Gabriel Voisin (right) to patent many ideas in the 1920s.

Pierre Cayla and Jacques Gerin devised such systems where oil and air were mixed to produce an effect. In that blend they were in advance of the simple air-regulated pneumatic suspension that the French company Delpeuch had devised in 1910. British pressurized air springing experiments emanated from the Cowey company in 1915. It would surely be wrong to link simple, fluidless air pressure regulating systems to the creation of a blended oleo-pneumatic system such as those devised by Cayla, Gerin and ultimately Citroën, who made the idea work on a mass industrial scale. The only other relevant, known, fluid-air experiments in shock absorbing were in France circa 1925 from the Messier company (now famous for aircraft undercarriages), which devised its own pressurized shock-absorbing suspension oil-bathed strut just after the early Cayla ideas.

Jacques Gerin, another obscured genius of the Voisin arena, and designer of a remarkable Aerodyne and numerous safety devices.

In summary, Cayla designed and patented his braking system. Perhaps by simply entitling it ‘hydraulic braking system’ he concealed its real significance and its later relevance to Citroën. For there were many attempts at hydraulic braking systems by many men, but the details of Cayla’s design may constitute a precursor to anti-lock brakes and to Citroën’s own hydro-pneumatic, pump-driven, self-regulating, ‘closed’-circuit hydraulic mechanism for brakes and as applied to suspension in unison.

Few have asked about, or even know of Pierre Cayla. Citroënistes know of Voisin, but what of the partially obscured Pierre Cayla? Certainly he should be recognized as another ‘father’ figure in the Voisin-Citroën story.

GERIN’S ‘AERODYNE’ – THE MISSING LINK?

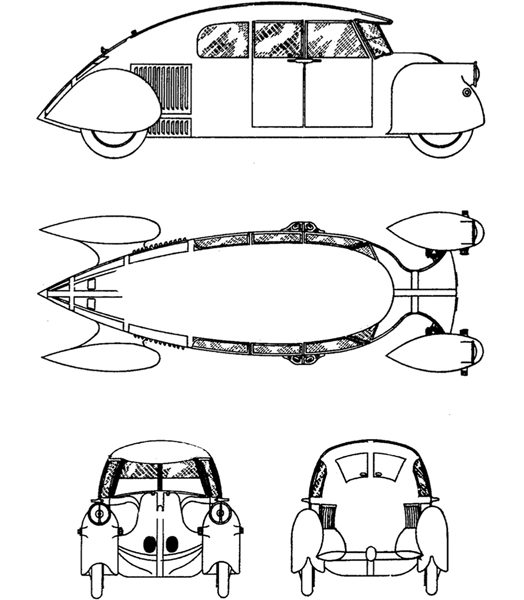

Another Voisin pupil was Jacques Gerin. He was an often forgotten genius of vision, and notably created a one-piece pod of an aerodynamic car, an ‘aerodyne’, between 1923 and 1926. It was a stunning piece of design, and could be construed as that ‘missing link’ between the early experimental years 1910–25, and the Art Deco streamliner movement of the 1930s and later works such as the Burnley Streamliner and beyond.

Jacques Jean-Marie Jules Gerin (1898–1973) came from Dijon, and his family had no known engineering connections or training. His education was interrupted by the Great War of 1914–18; he was drafted for pilot training, and ended up at Voisin’s early aviation school.

By 1923 Gerin had designed a propeller-driven car, with an independent suspension mechanism consisting of springs encased in oil-filled, sealed shock-absorbing cylinders – long before Citroën developed its 1950s oil-based system. Gerin’s prop-driven car, or ‘Helice’, was the subject of a patent application on 8 June 1923; this was granted on 1 December 1923 as French patent 567,154, for his ‘vehicule propulse pour helice aerienne’.

Gerin had created a suspension system that placed the springs inside an oil-filled sealed metal bath or reservoir, perhaps the precursor of later developments of the idea. He went on to design aerodynamic devices, safety systems that included an early form of crumple zone and safety cell, and other inventions.

For 1924, Gerin moved to Seine, Paris, to be at the centre of the action, and set up an office in the buildings owned by the Paulin-Ratier aeronautical and automobile company – helice builders, and who also worked with André Citroën. Before long Gerin had patented his design for an advanced, ellipsoid, low-slung aerodynamic car with a revolutionary form and function – it was an aviation-style, fuselage-built car, with a stressed spaceframe skeleton of duralumin hoops tied to an aluminium undertray.

Gerin’s one-piece single pod elliptical shape was of massive significance to car design.

Gerin’s design had features decades ahead of its time: flush fittings, a small frontal area, an elliptical profile and cross-section, allied to an alloy engine, advanced brake system design, an infinitely variable transmission, and suspended by lever-arm springs from oil-sealed spring casings. Many other cars subsequently used its themes, but no car used Gerin’s ideas before his Aerodyne. In its low slung design it presaged the Citroën Traction Avant, while in its podded shape it predicted the DS.

Jacques Gerin moved on from his Aerodyne in 1929. He designed a system for increasing the area of aircraft wings in flight – an early form of flap design that added lift at low speed. This was his ‘Varivol’ experiment, with advanced wing area and surface control – an early form of ‘slat and flap’ to create a ‘parasol’ wing. He also created an idea for a trans-Atlantic airliner, giving it advanced canard-type wings and a variable wing shape (long before Barnes Wallis).

By 1929 some aspects of international styling trends were evident in the all-steel-bodied Citroën line-up. This is a formal style of Citroën.

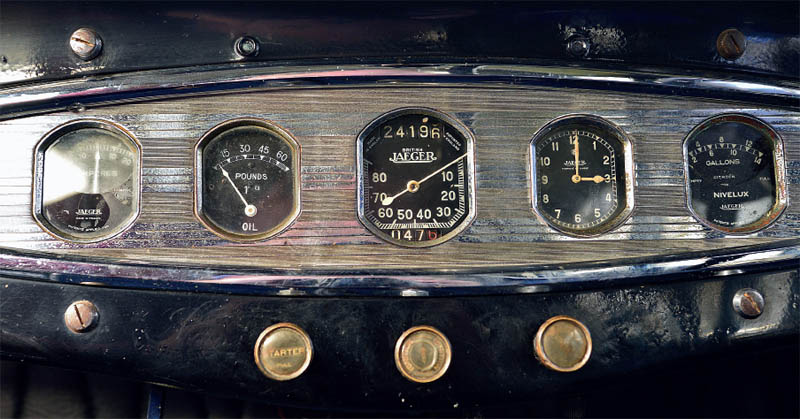

A wonderfully evocative Citroën C6 Berline dashboard design moment, and the beginnings of styling motifs. Even the Pope ordered one.

Plastique Fantastique

Perhaps even more spectacularly, post-World War II Gerin created not just a composite plastics process, but a composite blend that mixed glassfibre plastics technology with a blend of alloy fabrication and in-built metal supporting structures; this was a predecessor to the ‘sandwich’ composite plastics and metal now seen in airframe construction using a composite mix known as ‘Glare’ – a woven skin with a composite/alloy blended core. Only Lefebvre (with whom Gerin liaised) was a greater exponent of the new material, and as early as 1947 Gerin was experimenting with such advanced moulding technology – way ahead of the simple, floppy glassfibre one-piece mouldings that were to become so light and so dangerous in cars. Yet the Gerin Aerodyne disappeared from automotive consciousness and became a forgotten leyline in the automotive history map.

Gerin had immersed his suspension springs in an oil bath in the 1920s; by the 1960s he was developing reactive hydraulic suspension systems – reducing roll angles through controlling suspension resistance and introducing regulated roll rate interaction – and it is perhaps significant that Citroën’s own ‘active’ system was to mimic such thoughts.

In the late 1960s, Gerin concentrated on improving car safety in terms of crashworthiness through clever structural design. He designed impact-absorbing ‘crumple zones’, and built two modified production cars in the 1950s and 1960s: first the Renault Dauphin, the other his Citroën DS ‘Antishock’. To both cars he added his tubular ‘crush can’ impact-absorbing front structure, where the spare wheel was mounted near-horizontally at the front of the car to absorb impact. Crash tests included driving into a tree at 50km/h (30mph). The Gerin DS also featured pedestrian-friendly shock-absorbing plastic frontal bodywork cladding to reduce head and body injuries to impacting pedestrians – another instance of highly advanced thinking, and one that has only recently been featured in car safety design and on the 2005 Citroën C6.

Gerin died in obscurity, a man perhaps eclipsed by Citroën’s output of ideas, which were so similar to his own. Surely Gerin must be now cited as an influence upon the DS: indeed, it defies design logic to do otherwise. Jacques Gerin was truly a man whose mind was ahead of its time: he is the forgotten hero of aerodynamics, structures and car safety.

LE CORBUSIER AND A CITROËN HOUSE

Perhaps we can cite the astonishing visionary architect Charles Edouard Jenneret ‘Le Corbusier’ as another of the French design movement heroes who did not care for the constraints of convention and closed minds. Le Corbusier drove a Voisin, and featured Voisin cars in his publicity photographs for his constructions. He also knew and admired André Citroën – indeed in 1921 he built a house that he called ‘Maison Citrohan’8, a play on the name of Citroën, and in concept a ‘machine à habiter’ – a machine for living in. But the house was squared and cubic, not curved – as both Corbusier and Citroën design later became. The house was ‘like a car’, said the architect, an early Citroën car; in fact it resembled the juxtaposition of the bonnet and the upright windscreen.

Le Corbusier knew Voisin, Citroën, Peugeot and Michelin: he consulted them, and even planned a major industrial complex of glass skyscrapers to be built in Paris just north of the Seine, Le Plan Voisin. In such a plan, Voisin reflected a sociocultural thinking and status perhaps not unlike that which Citroën itself would achieve across the decades. Le Corbusier and his manager Monsieur Mongermon had sought funding from André Citroën in order to create new towns that reflected their new cars and the effects of them on life. In his La Ville Radieuse, Le Corbusier designed a town that would solve the traffic problems he anticipated the age of the car would bring – but it was too vast an idea for anyone to support. His designs featured high speed roads with an emphasis on aerodynamic cars of a type that he knew Voisin, Lefebvre and Citroën could and would produce.

For Le Corbusier, Voisin, Lefebvre and Bertoni, design ideology was to suggest the creation of a functional object with elegance and proportion, yet devoid of ornament (just as the DS or CX and others became so many years later). It is also interesting to speculate whether La Corbusier’s design for a small car presaged the 2CV in the mind of another arts and architecture expert – Boulanger. And Lefebvre would have been aware of Le Corbusier’s small call plans, as they were created with Voisin while Lefebvre was present. So there may indeed be a Le Corbusier link to the 2CV design concept.

L’Esprit Nouveau

Citroën design, its engineering and its ethos cannot have been immune to what was going on in Paris in this era. L’esprit nouveau – the spirit of the new, of daring to design to be different – was the essential motivation of the designers, architects, aeronauts and automobile men who were part of, or who created these movements.

It was as early as March 1916 that André Lefebvre entered the story as an employee of Voisin. And there can be no doubt that without the thinking and output of Voisin, Lefebvre would not have been trained as he was, he would not have been ingrained with the incredible engineering vision he latterly demonstrated for Citroën. Any observer in doubt of such a claim should perhaps look no further than Voisin’s C6 Course ‘Laboratoire’ cars, or the later C25–28 cars, and most obviously, the 1936 ‘Aerosport’, to see the influence not only of Lefebvre, but through these cars, the influence of Voisin upon Citroën itself. It was the great Gabriel Voisin who called André Citroën ‘This astonishing man’9.

For Citroënistes, the obvious questions are, how did the equally astonishing Citroën car company become the home of exotic engineering and advanced aerodynamics? And how did these qualities become the essential ingredients of Citroën – the soul of its being? The answers all lie in the DNA of Citroën, a DNA with many ancestors but which in part began with the input of several aeronautical engineers with an interest in art and architecture, notably Voisin and Lefebvre.

AERONAUTIQUE – AUTOMOBILE – MECANIQUE

So began the incredible story of Citroën. Through the amalgamation of chance and certainty, through the aggregation of design evolution and revolution, it all came together. France was the centre of the industrial design world – indeed we might say that France invented industrial design, and that André Citroën drove the process.

|

Low aerodynamic drag coefficient (Cd./Cx.) established in smooth teardrop-shaped bodywork with attention to sealing and excrescences. Open flow of air over and around the turret of the car to minimize airflow bubbling and detachment. Attention to pressure, lift and stability factors through applied design, mathematical calculus and wind tunnel work |

|

Small frontal area and low cross-sectional drag coefficient (Cd.a/Cx.s); Reynolds number defined |

|

Definition of the critical separation point to define rear drag wake off the rear of the car |

|

Wake tuning of base drag and lift |

|

Centre of aerodynamic pressure defined and tuned |

|

Movement of polar inertia known and adjusted n Light weight |

|

Low centre of gravity (cg), and the centre of gravity forward biased within the wheelbase |

|

Stiff chassis/body points at suspension mountings to ensure good handling |

|

Low suspension mass with inboard brakes to reduce roll centres and cg |

|

Front driven with the mass of the engine within the wheelbase to avoid pendulum or swing effect |

|

High speed from low power with engine/combustion process efficiency |

|

Predictable handling characteristics from advanced suspension expertise and tuning, creating ‘active’ safety qualities |

|

Front biased braking force |

|

Use of advanced techniques and synthetic materials to reduce weight |

|

Structural ingenuity |

|

Potential use of organic/sculptural styling elements |

Others, men such as Louis Renault (a long-time astringent to André Citroën’s thoughts) maintained a more conventional, fiscally ‘prudent’ mindset towards engineering and design. After all, too much aeronautically derived quality in car design could ruin its maker. It seems that the Renault company of that time was typical of the corporate sclerosis that stifles so many engineers and designers trapped in lumbering corporate structures. But even Renault later had to embrace front-wheel drive, and the concept of the 2CV to its Renault 4, even if it took years for the company to throw off the idea of rear-engined and upright contraptions.

As regards Peugeot, this esteemed family-owned company had occasional design extravagances, such as the Andreau-penned Peugeot 402 of 1936 – a lovely ‘Aerodyne’ attempt of the era, and one obscured by others. Peugeot also pioneered the ‘Eclipse’ metal folding roof, and created a lineage – yet it would be the 1960s before it found a more secure design language, an engineering and marketing niche of its own – and ironically, a time when it would ultimately own Citroën itself.

THE REASON WHY – CASTING THE MOULD OF CITROËNISM

Citroën’s engineering and design rationale encompassed key themes whose roots lay in marine and aeronautical experiments of about 1890 to 1920, and which became applicable to car design via early competition car knowledge.

Voisin and Lefebvre established these engineering themes long before their rivals, and when Lefebvre joined Citroën the knowledge transfer from aviation to automotive and from Voisin cars to Citroën cars was obvious. Throw in the scientific influence of Pierre Boulanger, and the resulting outcomes were the DNA of Citroën design.

Carrosserie Aérodynamique – a Sort of Aeromancy

The effects of a shape, form or body moving through smooth (non-viscous) water and air were long investigated, but these were the free-flowing effects of a form suspended in a single smooth element. What happened to airflow when it was forced to travel not only over or around and across a body shape, but when it was subjected to the effects of a road being close under that form or shape – in turbulent (viscous) air? This was the new science of road vehicle aerodynamics.

Furthermore, what were the effects of rotating wheels in wheel arches or panels, and of the protruding items on a car, such as wipers, mirrors and window seals or gutters? What was the point of a smooth clean shape if it produced lift that made the car dangerous – particularly extreme front or rear lift? And would pitching of the car by its suspension and braking forces, or its side-slip or yaw, make it aerodynamically unstable? From such issues stemmed the science of road vehicle aerodynamics and the Citroën obsession with it.

It might be argued by some that the French Art Deco carrosserie aérodynamique was intuitive rather than completely scientific, and that German research was more accurate; but the other side of the coin is that before Stuttgart claimed the plaudits, Paris and its auto-aeronauts were years ahead in their aerodynamic design research thinking.Through the early French researchers, the key elements affecting the creation of turbulence or ‘drag’ over a car, and its tuning to reduce drag, were revealed to be as follows:

|

Form drag – expressed as a coefficient of drag as a CD or more accessibly a ‘Cd.’ figure (Cx in French), created by the shape of the body itself as air passes over and off it (as base/wake and also as cross-sectional drag as CDA or Cd.a.). Likely according to generalized rules to account for approximately 60 (+/) per cent of total drag – and needs to reference the shape’s cross-sectional area expressed as S |

|

Induced drag – expressed as a CDi or Cd.i and resulting from the actions/effects of the body’s actions in airflow. Likely to account for approximately 10–20 (+/–) per cent of total drag |

|

Interference drag – as a resulting action of parts of the car’s shape on other aspects of the form in localized areas on the car. Likely to account for 10–15 (+/–) per cent of total drag |

|

Internal flow drag – the effects of under-bonnet and cabin airflow resistance patterns and expelled air behaviour. Likely to account for 10–12 per cent (+/–) of total drag |

|

Pressure effects, boundary layer and airflow separation point – such effects resulted from the actions that front grilles, windscreens, side panel and windscreen and roof profiles created close to the car’s body skin, and in the lee or downwash of localized effects such as that of a side force (YA), or bonnet and grille leading edge in front of an angled front windscreen and cabin turret or canopy. Positive or negative pressures (CP), notably the effect of unwanted or lift coefficient (CL) and its force (LA) allied to underbody effects, were vital issues and had significant effects on car performance |

Key facts were knowing the centre of gravity (cg), also the side-slip or yaw effects, finding the car’s movement of polar inertia, and studying where and how the airflow separated off the car as a critical separation point as vorticity patterns (CSP/SP). While all this is obvious today, it was unheard of in mass-market car design in the 1920s – but Voisin and Lefebvre were research pioneers in this field, and Citroën cars, starting with the Traction Avant, were the earliest road-going, mass-market cars to benefit from this knowledge before other car makers (notably Lancia) focused upon such issues.

Elemental Citroënism

On his own, André Citroën may well have emerged as an industrialist and car maker, and clearly he was a great man, but his works have a wider list of credits – he had that ‘dream team’ who created the Citroën engineering elements of expertise, elements not common amongst car makers: most car makers did not think like this in 1934.

In the essential Citroën elements we see the proof and the foundations of why Citroën design is evidentially far more complex and multi-disciplinary than has previously been explained. And if Lefebvre’s at times ‘wild’ futurism was reined in a touch by Boulanger’s mathematical mind, even that circumstance was framed by Boulanger’s creation of a design research practice at Citroën where science amidst Descartes-inspired psychology and free-thinking exploration constituted the foundations of Citroënism.

This was a unique set of circumstances leading to a unique process and a unique outcome – that of Citroën itself. And from such heady days, Citroën and its modus operandi evolved. Therein lies the explanation of the afterwards and the before of Citroën, and its first steps into an undreamed of future, a journey to the edges of rational design thought that touched not just big cars, but small cars as well. Here lies the answer to the why of the soul of Citroën, its DNA and its practice. As 1934 dawned the world of car design was about to witness the birth of the astounding Traction Avant. This was a car that would never have existed without the story as told herein, of the little known and wider effect of the 1920s design explosion in France and all the men who were a part of it.

So became Citroën as we know it, not least as producer of the world’s most aerodynamic mass production cars.