2CV

NOT BASIC AT ALL

|

NOT BASIC AT ALL |

SOME PEOPLE SAY that the 2CV is a basic, agriculturally engineered device, but nothing could be further from the truth. The 2CV was in fact a typical example of advanced Citroën intellectualism. In its austere functionalism it may have reflected architectural themes, but its graphically advanced body was a timeless stepping stone between the old and the new, though interrupted by a decade lost to World War II and its effects.

Inside Citroën and the Bureau were Lefebvre, Bertoni, Becchia, Sainturant, Franchiset, and before long, hidden in the engineering office, Mages. Boulanger worked well with these men, and it was he who in 1936 began to channel their talents into the very small car – or ‘Très Petite Voiture’ (TPD) idea that became the 2CV. The small car was Boulanger’s inspiration, but it is often forgotten that the idea had also previously been thought about by Le Corbusier, Voisin, Lefebvre and Bertoni – but it was Boulanger who made it happen at Citroën. Voisin and Lefebvre would continue to tinker with the TPD idea for decades in the form of the Biscooter and Cocinelle respectively.

Boulanger lived in the Clermont-Ferrand area of Lemdpes, and there, as a keen fisherman and gastronome, he observed how local farmers and suppliers struggled to transport and unload their wares on market day. From this came the idea for a rural hold-all – which became the 2CV.

Framed by the French fiscal ‘Système Chevaux’, the ‘Two Horses’ tag soon became TPD’s de facto name: 2CV – not as a fiscal rating, though over time it has erroneously become written as if it was. Some insist on 2cv, and many prefer ‘Deudeuche’ as a name. The 2CV was basic but advanced – that ultimate Citroën paradox. In its creation and construction, boundaries of engineering technique were explored. This was no agricultural dinosaur, as so many mistakenly thought: the 2CV was the result of cutting edge thinking of positively architectural origin.

The 2CV’s suspension was the first interlinked suspension design – via its centrally mounted, leading/trailing torsion bars – recognized as a patented (November 1938) device. With a new engine, new body and new suspension defining a new concept, the 2CV was revolutionary in the late 1930s, and far from the agricultural device so often portrayed. By creating new solutions to old problems and inventing a concept, the 2CV was in fact something truly new. Only in its terrible aerodynamics and appalling drag coefficient of Cd. 0.53 did the 2CV eschew Citroën thinking – but then, at the rural speeds the 2CV was designed for (about 35mph/56km/h), aerodynamic considerations were secondary. Cabin utility, ride and petrol economy were paramount.

Under Pierre Boulanger’s new lead and Lefebvre’s brilliance, the Citroën team began to craft the new device in 1935. History does not solve the riddle of the possibility of the car having any reference to the Le Corbusier small car design concept which had been entered in the Société des Ingénieurs de l’Auto design competition. Lefebvre knew Le Corbusier well from his Voisin days – but whatever the inspiration, the new small Citroën began to take shape from 1936.

Flaminio Bertoni’s styling buck for the production 2CV (post-World War II) is seen on p.66, and it clearly shows the distinctive and new form that Bertoni carved for the car. Unseen for decades, this styling buck shows how the original, more curved shape was evolved from its 1939 form into a production model. Bertoni’s sketching shows a car with three headlamps ‘cyclops’ style, and with sharper features; the third headlamp was soon dispensed with, and under Boulanger’s insistence the whole thing was toned down and made simpler and cheaper to make.

The pre-war prototype circa late 1938 featured a ribbed bonnet panel and much more curved styling than the post-war production model.

Compared with the production car, the prototype feels closer to Art Deco and Le Corbusier architecture than the 2CV as manufactured.

The car’s first iteration was in 1937, a sort of small tractor with a half cab and a twin-railed braced chassis with subframes. By late 1938 a proper saloon car type prototype had been constructed under Lefebvre’s lead, with Roger Prud’homme managing the actual construction of the car; Maurice Broglie was lead engineer. A new, air-cooled twin-cylinder engine was designed by Edmond Moyet; Alphonse Forceau created the three-speed gearbox. Marcel Chinon worked on the suspension with Pierre Mercier, and Jean Muratet worked on the body. The car was tested extensively by Pierre Terrason as the chief test driver and engineering department development man. Citroën’s La Ferté-Vidame test centre provided an ideal location for tuning the suspension and dynamics over many months by the team. The car weighed under 992lb (450kg). By late 1938, thirty-four prototypes had been built.

DURALINOX DESIGN

Lefebvre’s search for aviation style, strength and lightness led him to the expensive new alloy ‘Duralinox’ (an aluminium/magnesium dense alloy) for the major body panels, while lightweight sheet steel was stamped out for extremities such as the front wings.

The car was built up round a twist-resistant, steel sandwich floor ‘punt’ of H-frame type, with aircraft-style tubular reinforcing members, into which suspension forces were channelled. Mounted above this were the body members, formed principally by the bulkhead and rear wheel-arch pressings. Roof supports were minimal, and Bertoni added a touch of tension to many panels, not just for design reasons, but also to increase rigidity and deflect vibrational harmonics. The 2-cylinder engine was highly advanced, and a great deal of work went into the cylinder head and combustion efficiency process. For a basic car this was unheard of.

Special welding techniques, magnesium alloys and a waxed canvas boot-lid panel to save weight, were just some of the previously unthought of engineering delights of the car. Forty-seven pre-production prototypes were constructed, and a planned run of 250 cars in late 1939 was begun, though not fully achieved. During World War II the prototypes were hidden in various locations, and some were destroyed. The TPV, or 2CV to be, was put into a long, cold hibernation.

When it emerged in 1945 it was revised into something slightly different, and it would be 1945 before Walter Becchia produced the definitive 2CV’s 375cc air-cooled, twin-cylinder engine built in light alloy, yet still using a starting handle for rural reliability – though it was soon replaced with a starter motor. In 1946 Paul Mages and Leon Renault worked on an oleo-pneumatic suspension for possible use on the 2CV – but its concept was too advanced for the basic car. The advanced alloys and plastic inherent were replaced with materials that were easier to manufacture, and cheaper. Some of the philosophical intelligence of the original concept was diluted – though paradoxically, the production 2CV became more normal!

Key advanced design features were as follows:

|

Front-wheel drive |

|

Advanced engine and four-speed gearbox design |

|

Lightweight body of great structural efficiency |

|

Bolt-on outer panels |

|

Inboard brakes and low centre of gravity |

|

Open-top roof of fabric construction to allow large loads |

|

Removable seats and practical fittings |

Unseen for decades, and unpublished, this is Bertoni’s clay styling buck for the revised production design 2CV body.

Note the integrated front bumper/valance element and deeper windscreen shape.

Held in a private collection, this amazing buck shows us the perfection of form that Bertoni achieved.

PIERRE JULES AUGUSTE BOULANGER (‘PJB’): A PHILOSOPHY OF DESIGN ALLIED TO BUSINESS DISCIPLINE |

A product of the late 1800s, Boulanger led an interesting early life that must have helped create the open-minded and innovative thinking that latterly characterized his car design and engineering beliefs. Of note, like so many of the key players in Citroën, Boulanger had studied fine art and architecture before embarking on a more practical course. He was yet another product of the grand art schools of Paris. He was also exposed to military discipline at an early age, and the realities of war.

Boulanger served in the military from 1906–08, where the need for project management may have made its first mark upon him. He also met a member of the Michelin family, with whom he forged a friendship at this time. In an unusual move, Boulanger then spent several years in America in various jobs, including, it is reputed, as a ranch hand or cowboy; he then worked in architectural practices in Seattle, and also in Canada. Boulanger’s first foray into business was his building and design company that he founded in Canada.

At the beginning of World War I, Boulanger re-entered the military and took to the air as a navigator and photographer. Here he encountered the products of early aviation and of Gabriel Voisin. Commissioned during the war, the officer Boulanger became a decorated man and holder of the Légion d’Honneur. Upon the establishment of peace, he found his way to his old friends at Michelin, and entered the security of their employ. By 1922 he had risen to Board membership, and by 1938 was co-director of Michelin.

During these years, Boulanger had worked with cars and aircraft during the development of Michelin tyres, and the technology needed to serve these two expanding markets and engineering fields. It was in Clermont-Ferrand at Michelin that Boulanger developed his techniques of creating and managing research into product design and engineering needs, all wrapped up in a commercially viable management process. Boulanger was an ideas man, a design engineering thinker, but unlike some of his colleagues, he also framed a more practical style. This may have limited the scope of design experimentation by the men of the Bureau in one sense – we can ask if the DS was too advanced to have been a Boulanger concept, but we know that the type of car was a Boulanger idea. Boulanger adhered to an almost scientific mechanism of philosophy of discovery, but it is clear that he was neither constrained nor conceited by received or perceived practices.

Pierre Jules Boulanger – ‘PJB’ – seen pointing towards the 2CV at its Paris launch in 1948.

Boulanger’s abilities meant that he could identify market needs and grasp the essentials of product design. After Citroën’s bankruptcy, André’s death and the Michelin company take-over of Citroën in 1934, under Pierre Michelin, Boulanger became not just a corporate director of Citroën, but also the engineering and design leader. Safety was one of his key passions. He also saw the Traction Avant through its 1934 birth pains. And without Boulanger’s encouragement the Sensaud de Lavaud rotary engine prototype would never have been built. Some observers feel that Michelin and Boulanger were hard on Citroën, its staff and departments when they absorbed the bankrupt company, but it seems that Michelin and Boulanger had to apply tough business logic.

As president of Citroën after Pierre Michelin’s untimely death, Boulanger drove his ideas and those of his design team. In 1938 Boulanger’s lead gave birth to the Traction 15/Six, and soon after that he framed the team’s thoughts for a bigger, more modern car: the ‘VGD’, or ‘Voiture de Grand Diffusion’. Boulanger also cut costs and cancelled the Traction Avant 22CV. During the war he was forced to run Citroën by the German military, but he took several measures to undermine production for their war machine. Boulanger can be seen as the guiding hand behind the secrets of the Bureau d’Études and its stars; he encouraged the team to think the impossible, beyond convention, and when he learned of Paul Mages’ suspension work, he seized him from his basic draughting role and placed him and his ideas for Citroën into the Bureau d’Études and ensured that the system was first tested on a 2CV prototype, and seen in production terms on a late model Traction Avant.

Boulanger’s home in Lemdpes is now the Town Hall, and in 2005 the architectural firm of Bresson, Combes and Odet dedicated a new community building in Lemdpes in Boulanger’s name.

A keen driver, Boulanger made the regular journeys from the Michelin base to Paris and back in his personal Traction Avant 6-cylinder, a tweaked development car. In 1950 he tragically died at the wheel of this car. He never lived to see the ‘VGD’ arrive as the DS, but the men of the Bureau d’Études, and the men of Citroën who rose through its ranks, such as Pierre Bercot and Robert Puiseux, would carry the flame.

Contrary to the more recent perceptions of some people, the 2CV design was highly advanced: in fact it was the leading edge of thinking. Originally created before World War II, it would be 1948 before the car took to the road. Its subsequent longevity and production up to the 1990s are evidence that the original concept was sound and highly advanced. And the driving force behind the 2CV as a project, not just as a design, was a ‘thinker’: Monsieur Boulanger and his men.

LA FERTÉ-VIDAME: CITROËN’S SECRET SPACE

As early as 1938 Citroën had built itself a test and development centre for new models. The specially built road circuit allowed high speed handling and performance testing, as well as providing examples of differing road surfaces to test suspension designs. The test track was built in the grounds of a château originally purchased by André Citroën in 1924, situated 60 miles (100km) from Paris in rural Normandy. Numerous sheds and buildings and a management centre were constructed but most importantly, Citroën built a 7ft (2m 15cm) high wall around the entire 7-mile (11km) complex to keep out prying eyes and competitors spies.

In a link to Citroën’s own past, the site was previously used for farming and early aviation. All Citroën’s cars up until the late 1970s were developed at La Ferté-Vidame, and when Peugeot took over Citroën, it continued to be a test and development centre for both marques. The three original 2CV prototypes were hidden in the attic of a barn at Le Ferté-Vidame, where they survived the war and German occupation.

In the early 2CV years, La Ferté-Vidame was managed by a Monsieur Clerc, and a Monsieur Terrason was the senior test driver for the 2CV development team. A wind tunnel was latterly built at La Ferté-Vidame, and this was run by a Monsieur Girardeau. Development was concealed during the war years, and the 2CV’s actual concept was kept hidden from the occupying forces; however, Citroën did continue work on the 2CV during the war, somehow convincing the German authorities that they were working on a military vehicle. By 1945 the team, now with Walter Becchia on hand, got to work to finish and actually revise the original 1939 2CV design concept.

By 1947 this weird yet wonderful piece of advanced engineering thinking was nearly ready, and those who dismissed it because of its appearance would soon regret their judgement.

THE 2CV DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT MEN |

Walter Becchia |

André Lefebvre |

Maurice Broglie |

Jacques Leonzi |

Jean-Claude Bouquet |

Pierre Mercier |

Pierre Boulanger |

M. Meunier |

M. Caneau |

Edmond Moyet |

M. Chataigner |

Jean Muratet |

Marcel Chinon |

Maurice Norroy |

Jacques Duclos |

Roger Prud’homme |

Alphonse Forceau |

Georges Sallat |

M.Geel |

M.Steck |

Lucien Girard |

Pierre Terrason |

Pierre Ingeneau |

|

Some changes were made to the 2CV’s suspension in its early life. Originally its front and rear bell crank lever arms pivoted to create a vertical axis, and springs each side of the car linked the suspension longitudinally via the lever arms. This springing unit consisted of two opposing springs contained within a cylinder at each side of the car (underfloor mountings). At the 2CV’s launch the springs were pre-loaded under compression, but by 1954 the system was altered so that the action of the springs worked under tension as the lever arms worked as tie-rods. Extra volute-type springs were loaded into each cylinder. The 2CV’s ability to roll to high angles without inverting itself was down to the very low roll centre formed by the low-mounted wheel hub/carrier link to the suspension, which avoided vertically aligned loading up.

2CV MODEL DEVELOPMENT

1937–39: Prototypes and early build series cars.

1947: Revised body design.

1948: Launch of definitive 2CV with 375cc engine at Paris Salon.

1949: June. First full production: 971 cars made in 1949.

1950–51: First 3,000 cars built.

1951: 2CV AU Fourgonette van with 550lb (250kg) payload announced with smaller 375cc engine but lower final-drive ratio of 7:3:1 and larger 135 × 40 section tyres; AU van latterly with glazed panels option.

1953: First British Slough-built cars with specification changes and metal boot-lid. First British 2CV vans.

Latterly followed in 1957 by British-built pick-up variant.

1954: Larger 425cc engine introduced, and twin tail lamps. AZ designation. Light grey paint.

1954–55: Centrifugal ‘Traffi-Clutch’ option.

1955: Changes to design of suspension mountings.

1957: AZL and AZM designations for saloon.

1955: AU series vans are given larger 425cc engines and new AZU designation.

1957: Metal boot-lid replaces fabric on all French 2CV Ss.

1960: ‘Blue Glacier’ paint offered in France; British 2CV production stops.

1960: Twin-engined 4×4 Sahara using Voisin-type mechanicals introduced.

1964: Front-hinged doors deleted and rear-hinged doors introduced for 1965 model year.

1965: ‘Six-light’ windows with rear side windows added to C-pillar.

1968: Ugraded ‘Berline’ model; ‘Commercial’ model.

1969: 602cc engine fitted.

1970–75: Numerous trim, colour and specification changes. Different headlamps.

1972: Paris-Kabul 2CV Rally. Launch of first 2CV Cross events.

1976: 2CV Spot edition.

1977: AK 400 van production ends; the Dyane Acadiane replaces it.

1978–86: Special Editions launched, culminating in Boat France 3, Bamboo, Beachcomber, Dolly and latterly the 2CV 6 Charleston of 1980, James Bond in 1982, Dolly, France 3, Cocorico.

1990: Production ceases in Portugal after just under 4 million cars have been built.

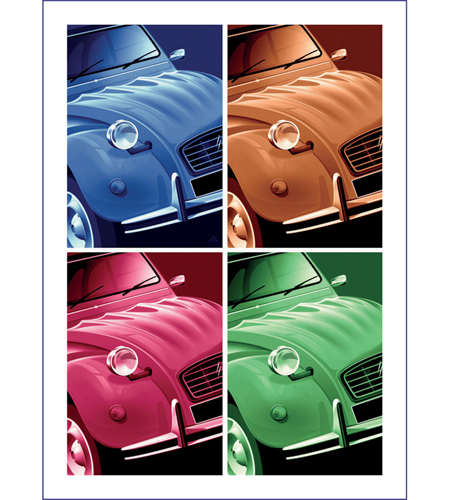

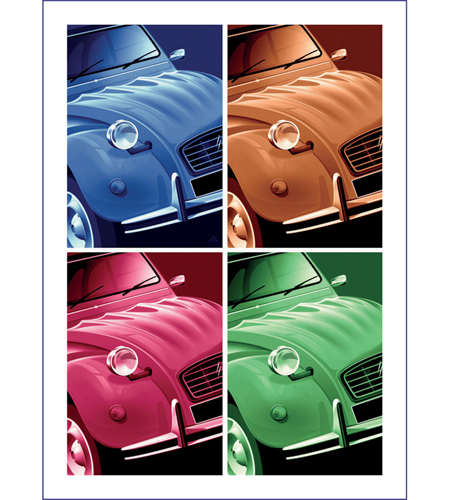

2CV Spot special edition and an Ami Super show off their Bertoni lines.

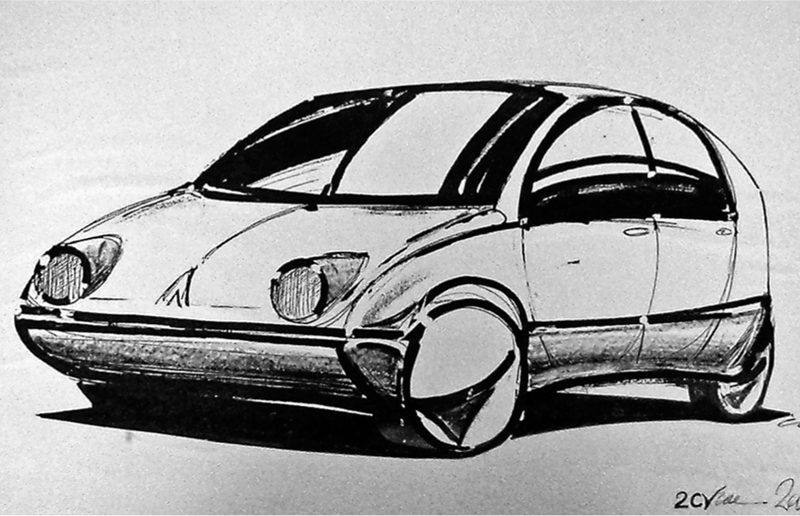

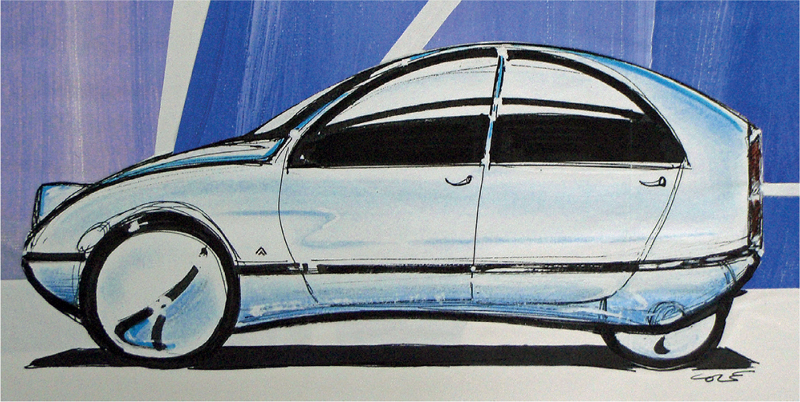

Many designers have attempted to recreate the 2CV. Following previous design experience and working on a PSA project, this is the author’s 1994 anti-retro design idea for a ‘new’ 2CV; it was featured in the motoring press.

The author’s 2CV design featured flying buttress C-pillar and wheel spats, but was not a retro-pastiche.

ARGENTINIAN 2CVS

The first 2CVs imported into South America arrived as early as 1958. These were imported by Staudt and company, yet by 1959 Citroën Argentina S.A. was in existence. Early cars were CKD, but by 1962, local toolings and pressings created the true Argentinian-built 2CV from Buenos Aires. Production also took place in Venezuela.

The first Argentinian 2CV range consisted of saloon and the rare van/pick-up variants. These cars were tagged 2CV AZU/AZL, and had the12.5bhp 425cc engine. For late 1963 a 14bhp version with better breathing boosted sales in 1964 to over 5,500 cars. It is reputed that the Argentinian cars received the third-light rear window very early in the 1960s, before many other markets. In 1965 more power at 18bhp and revised interiors updated the Argentine range – as did the addition of changes to the clutch mechanism. For 1966–67 van production was increased. Production ceased in 1972.

In 1967 opening rear windows in the rear doors of saloons were added. Also local van production started: the 2CV Azam was made until the end of 1971, and the 2CV AZM until March 1972, when production ceased permanently after an amazing 64,644 cars had been produced with various badges and names.

Special one-off body conversions based on the saloon and van bodies were produced for the Argentine market, and these are now highly prized. The complex and rare Argentinian 2CV trim and variants included the 2CV, 3CV, AZU, and Fourgon.

2CV STATESIDE?

Citroën toyed with the idea of importing the 2CV into America, and a small number were sent over in the mid-1960s for evaluation. But the mindset of the American car-buying public resisted the 2CV’s charms, though a few were tempted. But in 1970 Citroën gave up any hope and abandoned its US dealer stock. It is believed that up to 900 2CV s made it to America circa 1964–70. The remaining US stock was crushed by Citroën in America in order to save the costs of repatriation to the motherland!

Not only were special versions of the 2CV built around the world: a series of self-build cars that even have their own ‘Citroën Specials Club’ now exists. The 2CV basics, minus the body, seem to provide an enduring base for many interpretations.

Leading 2CV special-bodied cars include Lomax, Pembleton, Hoffman, Le Patron, Burton, Azelle, Charou, Alveras, Tripacer, BRA, Falcon and Deauville. Some use 2CV parts, others Dyane, Mehari, and even GS components. The popular Lomax comes in either two- or four-wheel variants. Most of the specialist marques use glassfibre for their bodywork, although alloy-fabricated bodies have been produced. The Hoffman-bodied variant uses 2CV body panels in a cut-down two-door convertible shell. The Burton special apes the Deutsche and Bonnet aerodynamic styling as seen on the one-off 1930s Traction Avant aerodynamic study.

Leather-lined 2CV interior – the Hermes collection special edition 2CV.

2CV interior sumptuously done out in leather.

‘Mildly modified’ might begin to explain this 2CV mud-plugger.

The Citroën Specials Club caters for the glassfibre and rarer steel-built ‘kit’ cars based on 2CV underpinnings and engines.

2CV Cross – a wonderful sport.

Variations on a Theme

|

Jean Dagonet created modified and tuned 2CVs as early as 1953, and by 1954–55 he had re-bodied a 2CV with an amazing, curved, low-drag body of lozenge-shaped, Bertoni-esque elegance |

|

In 1954 the racing car fanatic and car designer Phillipe Charbonneaux created his own take on the 2CV as a ‘pontoon’ type design |

|

In 1953 Pierre Bardot produced the first tuned and modified 2CV for racing |

|

1955 the 2CV ‘Bicéphale’ was used as a fire brigade ‘Pompier’ lightweight hold-all-type van with modified steering to allow manoeuvring off road |

|

In 1956, Henri Chapron tackles the 2CV with a modified bodyshell with an estate car-type rear end as a 2CV ‘Break’ |

|

By 1959 Citroën’s Chilean factory is producing the Citroëneta – itself a three-box, booted 2CV. For 1963 Argentian-built ‘La Rana’ 2CV s with bodywork changes were produced |

|

For 1960 the Citroën produced the 2CV ‘Sahara’: it has 4×4 via two engines and two gearboxes mounted front and rear. Less than 700 are built, and in 2013 a rare survivor once owned by the Dupont family sold for over $140,000 in America |

|

In the 1970s, the 2CV-based ‘Africar’ project blended 2CV mechanicals and a composite and wood body in an attempt to realize a dream of low-cost travel in the developing world. Despite its brilliance, Africar failed |

|

The 2CV Contessa was a 1970s Spanish-built re-bodied four-light window version using the standard 2CV mechanicals and platform |

|

The Citroën Mehari was a 2CV/Dyane-based plastic-bodied derivative; there were also glassfibre and steel-bodied versions built as the Tangara, Pony, Baby Brouse and other iterations |

|

As late as 1988 a 2CV 4×4 concept-derived car known as the Katar was built in France by SIFTT as an all-terrain vehicle with the enlarged 652cc twin-pot engine from the Visa. |

|

In 1989 the 2CV 6 Charleston special edition was imported into America by Michel Fournet. It is reputed that he circumvented US Type Approval regulations by transferring the new cars’ bodies and engines into a refurbished, previously registered 2CV base. |

Some owners go to great lengths to smooth down and lighten their steeds.

2CV in ‘Charleston’ graphics.

SPECIFICATIONS |

2CV/2CV4/2CV6/VAN VARIANTS 1948–90 |

Body

Lightweight alloy/steel body panels mounted over steel base unit platform. Four- and six-window designs. Fabric roll-back roof. Numerous changes to roof, bonnet and boot-lid designs

Engine

375cc air-cooled twin-cylinder: 425cc, 435cc, 602cc. Front-wheel drive

Transmission

Four-speed manual

Suspension

Horizontally mounted friction dampers and shock-absorbing system with interconnectivity

Brakes

Drums/front inboard mounted, hydraulic operation

Dimensions

Length |

152in/3,860mm |

Width |

58.5in/1,480mm |

Height |

63in/1,600mm |

Wheelbase |

94.5in/2,400mm |

Weight |

1,235lb/560kg (unladen) |

DAGONET, UMAP AND THE 2CV

In the early 1950s, French engine tuner, after-market specialist and rally driver Jean Dagonet came up with an idea for a re-bodied 2CV using a decidedly Bertoni-esque, teardrop-shaped, low-slung five-door iteration of a coupé style moulded in glass fibre. This was mounted on a 2CV platform and using a tuned 2CV engine. Several were manufactured, and this led Dagonet to the idea for a less radical, two-door coupé on the same underpinnings. In 1956 Dagonet began to make a master body for a mould.

The very rare UMAP glassfibre-bodied 2CV two-door project. Only two or three road-going survivors are known, and the location of the moulds is not known.

The ensuing events are clouded by a lack of records, but basically, a small company, known as l’Usine d’Moderne Applications Plastiques, run by Camille Martin in Bernon, France, created their ‘take’ on the standard 2CV. This was a two-door coupé-type glassfibre car on a standard base platform. The idea was to clothe it in an elegant glassfibre body that belied the humble origins and low capacity engine hidden under the Franco-Italianate style of the body.

It is an oft debated question as to who shaped the car – was it Monsieur Martin or Jean Dagonet? Several references credit Jean Dagonet with the original project, and cite a subsequent completion and separate production by UMAP. This could be because after manufacturing his teardrop-shaped, re-bodied 2CV, Dagonet embarked on building a two-door body that the UMAP resembled, to some extent. There was also a Jean Gessalin who was consulted on the car’s construction process, so maybe all three men had a hand in the shape. The car was deemed attractive by many, and more sporting (but actually less aerodynamic) than the later British-based 2CV Bijou of similar idea.

From 1957, a small local production run of the UMAP-branded ‘425’ and ‘500’ models of this two-door, two-box coupé body were made, the 500 featuring a bore-out twin-pot engine of 499cc from the original engine capacity. The dashboard featured parts from various Citroën cars and commercials, but it is not known where the windscreen and windows were taken from – unless they were commissioned items, and Renault parts may be apparent. UMAP’s body design was neither avant garde nor particularly aerodynamic, but it was smart, had shades of Simca and Renault Caravelle in its lines, and was therefore entirely contemporary.

Citroën did not officially support the car, nor did it supply new parts direct. The list price was high, approaching that of an ID, and the car briefly appeared at the 1957 Paris Salon. Production records are not available, and the much touted build run of 100 cars is a claim that seems unfulfilled – experts say that forty-seven cars may have been built. Two UMAP 500s took part in the 1958 Liège-Brescia-Liège rally.Today, only two UMAP cars are roadworthy, and the location of the moulds is unknown.

The ABS-bodied Méhari used many stock items, yet managed to look individual.

MÉHARI: PLASTIC DROMEDARY

Often cited as a 2CV derivative that might ape the 2CV 4×4, the Méhari (so named after a Sahara Desert camel or dromedary, and also cited as the French Army Africa regiment who were camel-mounted and thus ‘Méhariste) was closer to Panhard and the Dyane. The very first technical references to the car cited it as a Dyane-Méhari.

In its element, Méhari flies through the mud.

Based on the platform of the Dyane 6, the Méhari used acrylonitrile butadene styrene (ABS) plastics moulding technology in its open-top body, which composed of only eleven or thirteen actual mouldings, depending on the variant. Underneath the ABS formed body was a Dyane platform and engine caged by tubular steel support structures. Of significance, the Argentinian market (Uruguay-built) Méharis and certain others used the glassfibre resin body technique because it was much cheaper to manufacture – thereby removing the need for ABS moulding costs. Early development of the idea in 1966 is credited to a Roland de la Poype.

With the 2CV/Ami twin-pot engine’s 28bhp on tap (and latterly 30bhp), the car’s light weight of 1,300lb (570kg) created a ‘go-anywhere’ animal that was limited only by its small torque – which the fitment of a reduction gear in the 4×4 variant slightly ameliorated from 1979 to 1983, late in the Méhari’s production life. With the long travel, loping suspension of the 2CV, narrow tyres, low centre of gravity and light weight, the Méhari was a camel- or maybe even goat-like adventure vehicle ideal for military, agricultural, adventure and leisure use. Over 145,000 Méharis were built.

An American market version was sold as a truck to circumnavigate the US Type Approval regulations. Because it was required to fit bumpers and raise the headlamps to meet local rules, a new front valance moulding had to be created – yet only 214 Méharis were sold in America. The car hire company Budget sourced Méharis for hire to tourists in Florida and Hawaii. Most Méharis were beige, but later 1970s colours included orange, yellow and green. A rare Méhari ‘Azure’ edition was blue and white and had deckchair-style striped seats instead of plastic coverings.

Here, the moulded chassisless ‘punt’ reveals the core of the Méhari prior to its eleven main body panels being fitted.

Handbuilt at the factory, a Méhari with full roof kit is nearly complete.

The Méhari derivatives were often made in cheaper glass fibre or basic steel panelling. This is the ‘Pony’ variant seen in yellow paint.

The Méhari went rallying in the 1969 Liège-Dakar rally, the 1970 Paris-Kabul-Paris rally, and then the 1971 Paris-Persepolis rally; a single Méhari was used as a support vehicle in the 1980 Paris-Dakar Rally.The French army ordered many Méharis and converted them to 24-volt specification. The Irish military also purchased a small number (ten to twelve) of Méharis, finished appropriately in green. The Méhari 4×4 had a four-speed gearbox with a three-speed reduction/transfer box. From 1979 to 1982 the 4×4 version received various trim and specification upgrades from the 2CV and Dyane parts bins.

Steel-bodied versions of the Méhari were licence built, and a ‘Baby Brouse’ variant was built (up to 30,000 were made) in Africa and in Vietnam as the ‘Dalat’ for Asian markets. A ‘Pony’ variant was known in Greece and Turkey. A ‘Tangara’ variant was also created, comprising the amalgamation of 2CV, Dyane and Méhari components and often crudely built in local steel. Citroën even reverse engineered its own steel-bodied version, known as the FAF.

The Méhari was never officially imported into Great Britain, but instead was made available via official Citroën dealers as their own imported stock. Over 100 Méharis were sold in Great Britain, and approximately thirty-five remain known as running, but records are inaccurate and the name ‘Méhari’ does not appear on registration documents (‘Citroën Two-Seater Utility’ being the usual description).

Although without either safety belts or impact protection, the Méhari proved hugely popular and today has a growing following and rising values.

MÉHARI DETAILS |

Launched 1968. Withdrawn 1988 (France)

602cc, two-wheel, front driven

Later 4×4 variant launched in 1979 with approx.

1,275 built

Open top, canvas roof (later plastic roof option)

CITROËN IN BRITAIN

Citroën’s early agents in Great Britain were Gaston Ltd of Larden Road, Acton, West London. A showroom in Great Portland Street was a rather grand tangent, but Gaston also had a city centre Piccadilly outlet. Citroën appointed Harrods as their agents, and Harrods soon had a fleet of Citroën vans.

The link with Slough, just west of London and not far from the end of Heathrow Airport’s main runway, came about from a demonstration of an autochenille tracked vehicle at the site of the then Slough munitions site, which soon developed into an industrial and engineering facility. By 1924 Citroën in France had decided to take over the operations of its British agency outlet, as the Gaston company was struggling. Citroën’s first ‘official’ showroom and base was in Hammersmith. Within two years, and allied to a new British import tax, the logic of making Citroën cars in Great Britian became obvious.

On 18 February 1926 André Citroën opened the marque’s new British base on the Slough trading estate. A major coup was to usurp Renault as suppliers of London taxis. Latterly, British-built Traction Avants were converted to 12-volt function and had British trim options, including differing dashboards and seat trims; they were even sold across the British Empire as the ‘British-built Citroën’. Many Lucas parts were also used to increase the local British content. British 2CVs were pitched at a British customer base, but sales failed to take off in the early days. Slough-built 2CV vans were also produced, and 231 were sold.

Citroën GB’s Nigel Somerset-Leake, with approval from boss Louis Garbe, created the idea of an agricultural version of the 2CV: a pick-up. Along with his managing of the Bijou project, Somerset-Leake seems to have been an inspired ideas and marketing man. The special 2CV pick-up truck was built for a Ministry of Defence contract, and featured a handbuilt, locally engineered rear cab tooled up by metal bashing a ‘master’ over a concrete mould and using H van components. The mechanical guru of Citroën GB, chief engineer Ken Smith, worked on this project, which also took place as the factory was being rebuilt for British DS production. The 2CV pick-up sold sixty-five units to the public, and approximately sixty-five were also sold to the Royal Navy.

Air-cooled engineering as originally intended.

The interior of the van reeks of utilitarian functionality.

The 2CV was produced as a Slough-built car with modifications for local tastes that included a metal boot-lid and a revised roof in a more durable ‘Everflex’ material that allowed a larger rear windscreen; it was also fitted was a wonderful Art Deco-style bonnet badge. Lucas semaphore trafficator arms were retro-fitted, as were folding rear side-window mechanisms. Chrome bumpers and over-riders were added to the British cars, of which 1,034 were built between 1953 and 1960 (672 saloons, 231 vans and 131 pick-ups).

2CV owners are individualistic, and this one has well and truly ‘tripped the light fantastic’.

As early as 1953, Citroën in Slough also produced a one-off 2CV with taller roof pressing and larger windscreen for a British customer of great height, a Major Wanliss, who could not fit into the standard car with its generous headroom. This car was chassis number 8530102, and at one time bore the registration number STJ 113.

British DS production began in 1956, and again, many local trim variations were made, including the British-style wooden dashboard, and numerous technical and styling tweaks. Early DS/ID19 production also relied on SKD base units being shipped in via the boat train until the expanded Slough factory could ramp up to full production. Between 1956 and 1964, 8,000 DS cars were British-built, with a further 500 SKD kits added. But at this stage, Citroën ended British production, closing a four decades long chapter in its relationship with British production. The company would remain at Slough until further PSA rationalization in recent years.

BRITISH BIJOU

The apparent early failure of the 2CV in the British market place led to an interesting idea – that of a more upmarket, more middle-class sort of faux coupé based on 2CV mechanicals. A better looking, more conventional car would, it was suggested, appeal to the more conservative British buyer. Pricing was also an issue: at £560 a new 2CV, even Slough-built, was not cheap in comparison to other small cars of the day, which retailed for around £400 to £450.

Citroën-Slough’s sales manager Mr Nigel Somerset-Leake is credited with progressing the idea of reshelling the 2CV with a glassfibre two-door body – and often unmentioned is British Citroën director Louis Garbe, who is reputed to have suggested the idea. Garbe was also the man who happily sanctioned ‘improvements’ to British-built 2CVs long before such items were specified in Levallois-built 2CVs. Citroën Slough’s chief engineer Ken Smith was also involved, though his main remit at the time was organizing the start of British DS production.

Glassfibre, or ‘grp’, was a new plastics-based material that had stemmed from wartime technology: it was much cheaper to manufacture curves in grp than in metal. Unlike other grp pioneers, the Bijou, as it was named, did not have a single one-piece moulded shell draped over its chassis: instead, Peter Kirwan-Taylor – who was a ‘petrol head’ and a design enthusiast with a clever eye for detail – created a separate section, multiple moulding grp monocoque of much higher strength than a one-piece moulding. With a grp central tub and separate grp outer panels, this car had a strong cabin cell and was much safer than a normal one-piece grp body: it ensured that frontal impact was better absorbed, with less chance of the body shattering around the cabin structure’s apertures, as is often the case with the alternative one-piece moulding.

The Bijou was an elegant and aerodynamic car that surely should have become a fully available Citroën product across Europe.

Often cited as the Bijou’s designer, Kirwan-Taylor was a businessman by profession, with a passion for cars and motor sport, which led him to be a key player within the corporate hierarchy of Colin Chapman’s emergent Lotus brand. However, we can only speculate as to the role that Kirwan-Taylor’s associates, the designer Ron Hickman (once of Ford) and the aerodynamics guru Frank Costin, might have played in shaping and engineering both the Lotus Élite and the Citroën Bijou.

The Bijou was devised with a similarly constructed body to that first used by Lotus on the grp monocoque of the Élite, but the construction costs were high, and Lotus soon switched to a cheaper, but structurally less advantageous one-piece single moulded shell mounted to a central chassis spine for all subsequent Lotus grp cars.

Bijou was a masterpiece of integrated styling, with shades of Bristol about its cabin and glasswork. It remains an often forgotten highlight of early grp car design. Due to its multiple-section moulded hull (and metal platform underneath), it was not as light as a single-skin grp-shelled car would normally be, and this affected the gears’ performance until aerodynamically relevant speeds were reached.

Kirwan-Taylor must have had access to a great deal of aerodynamics knowledge, and not only gave the little Bijou hints of DS style, but also excellent wind-cheating shape and details, thereby offering very low drag with a resultant cruising economy of almost 60mpg (4.7ltr/100km). Unsurprisingly, Citroën GB endorsed the car and sold it through Citroën dealers. At £695 it was not cheap, but it was stylish and economical, and was linked to a national dealer network. We can only wonder why Citroën did not do a deal to secure the car’s rights for European marketing in a left-hand-drive version.

Built between 1959 and 1964 at the Slough factory (with two attempts at securing a moulding supplier after early moulding issues), Bijou was never made in left-hand-drive form and never sold abroad – although six were exported to Australia. Of the 203 claimed production Bijous (and at least two prototypes that featured differing front styling), less than twenty remain. The engine was the 2CV’s 425cc twin-pot with a ‘Traffi-Clutch’ mechanism as standard. The car used Lucas electrics, and parts from the Citroën DS, Citroën Traction Avant, and Morris and Standard-Triumph ancillary fittings: the facia design was particularly clever for its era.

The car was produced in low numbers for just over four years, and the final production figure is cited as an indeterminate 205 to 211 units – which must surely count as a success for a private idea, endorsed by a car maker and up against stiff competition in a new market. Today, the Bijou is a coveted example of a uniquely British Citroën design.