BRAVE SIBLINGS

AMI AND DYANE

|

AMI AND DYANE |

IF THE DS was Citroën’s new hallmark, its international legend, what could it offer the more traditional car buyer? And how could it target the new emerging market of female car drivers? With so much emphasis on its new DS spaceship, Citroën was in danger of being perceived as having gone upmarket and of leaving its core buyer base, notably its French audience, way behind. And could a new, smaller car capture buyers across Europe, even in Great Britain, or even more daring, in the USA?

Everyone wanted a DS in one form or another, but not everyone could afford one, or even the basic, stripped-out ID austerity model which the company soon came up with in 1957. But would Citroën create a new ‘half-way-house’ type of car, something bigger and better than a 2CV, yet below the DS’s market sector? Given French fiscal tax ratings – hence 2CV, 7CV and so on, the car was thought of and spoken of internally as the ‘3CV’ in reflection of its intended engine tax rating size.

However, wouldn’t such a new size of car require an expensive new body, suspension, floorpan and range of engines? And surely all this would take at least five years to develop, never mind the funding issues or factory capacity required from an already over-stretched Citroën. In 1959, nearly five years into the life of the DS, and just as the first revisions to its front bodywork and mechanical and trim specifications were being enacted, the men of the Bureau d’Études were given the go-ahead to start sketching out ideas for a new small saloon. As for the floorpan, engine, tooling and specifications, it was decided that these could wait, because first it had to be styled to be different and new – not a mini DS, but something in its own right.

STYLING – BERTONI’S LAST GREAT FLASH OF GENIUS?

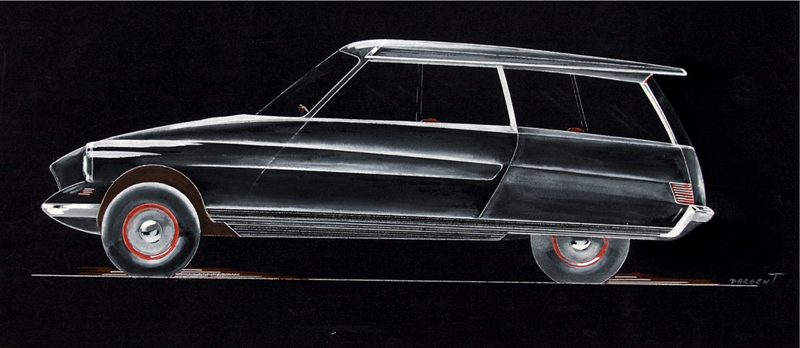

Enter maestro Bertoni and his gypsum, clay and sculptural skills. After the success of his DS styling, Flaminio Bertoni’s stock was high. By now he had also been joined by the talented Henri Dargent and R. Henrique Raba, and André Estaque. A Monsieur Lattay was the man who assisted Dargent with the early Ami styling models.

The ‘Ami’, as it became named, was again a car body design teased out by Bertoni’s hands, but unlike the Traction Avant, early ideas were committed to paper, and a definite feel of the 1960s soon became apparent. The reverse raked rear window had already been seen by 1957 in America on the Mercury Turnpike design, and had been tried on various Packard and Lincoln design studies. But its use in a small saloon was a new approach. The Ami may have lacked ‘fins’ in the idiom of the day, but with its tailored rear design, long rear boot deck, four round, chrome-rimmed rear lamps and deep body side swages pressed into the steel from the front wings through to the rear, the car had a glitz or glamour no one was expecting. It was a great piece of integrated, Franco-Italian styling, with some of the glitter of the new age thrown in.

Only at the front was Bertoni frustrated: he wanted a sharply dipping frontal aspect, a ‘face’ for the car which would have had an aerodynamic scoop for a grille bordered by two subtle wing lines with headlamps recessed into each side. However, the constraints of tooling, the height of the engine block and the need for under-bonnet venting for the air-cooled engine, all contributed to robbing Bertoni of his radical and futuristic plunging frontal style.

Despite this, the Ami was a pioneer of the use of squared, shaped headlamps, and these were set in chromed housings; Bertoni also managed to incorporate a hint of his original front apron and low bonnet idea by giving the car a strong visual scoop in a concaved and compound curved bonnet pressing that must have given the toolmakers consternation – but it made it to production.

Observers often miss the subtle ribs pressed into the steel of the front wing behind the wheelarch: were these a ‘faux’ suggestion of air vents, or an expensive piece of design? They were deleted in the 1968 body changes. Across the car’s front below the headlamps were two parallel trim strips that were smoothly chamfered into the front apron, with the turn indicator lenses designed to sit between them. Again it was stunning, simple, pure design – though it was soon removed in the cost-cutting days that lay ahead.

The Henri Dargent rendering of an idea for a three-door car of Ami derivation, dated April 1962.

Inside lay a ‘space-age’ dashboard, and seats that could be removed for outdoor use. It seems that Bertoni put all he knew and intuitively felt, into this wonderfully designed car.

With its domed roof ending in a sharp, Kamm-type ridge and with the rear boot deck acting as a de facto spoiler, the Ami was a blend of style and science allied to an anthropomorphic style of sculpted integrity. The original Ami 6 Berline is a long-forgotten piece of singular design excellence; sadly it has perhaps been shrouded by its simpler, more ‘normal’ derivatives of the late 1960s.

Much as Bertoni adored the DS, it was a modified shape, whereas in the Ami 6 Berline it was his own pure shape that had won through (minus only his scooped airflowed front end): it is reputed that this car was Flaminio Bertoni’s favourite piece of design work. Looked at from the present day, it is indeed a stunning blend of science, future fashion and elegance, which may also look more French than just about anything else of similar stature. Is this one of the most original, individual, elegant, organic car shapes ever seen and often forgotten for its excellence? There are no excrescences, no gimmicks, just wonderful 1950 to 1960s ‘space age’ styling moulded into a quintessentially French form.

The incredible dashboard built on DS themes.

Ami Berline with classic rear screen angles and pure Bertoni style. No wonder it was his reputed favourite design.

Building the Ami. Note the triangulated footwell reinforcement pressings and strong bulkhead. The sill gauge remains somewhat thin.

Under the Skin

As the styling team thought about the new car’s shape, Citroën’s management took the decision to use the underpinnings of the existing 2CV for the car that would become the Ami. The rear inner wing panels, floorpan and other existing 2CV metal pressings were amalgamated into a new body to which a much stronger front cabin tooling was added. Given the lightness of the 2CV’s front cabin construction, Citroën’s engineers created a strong, one-piece pressing for the A-pillar and windscreen aperture panel. This was welded to a strong bulkhead that featured triangulated footwell sections at each side; these also provided an early form of anti-intrusion device behind the wheelarch area. The roof was attached to a rigid perimeter frame.

In the fashion of the time (and of the DS), the main vertical B-pillars were thin and the floor flat. The car used box-section sills, which were somewhat light in gauge. At the rear, a capacious boot projected behind the reverse-angled rear windscreen. Up front, lightweight external front wing panels and a deep frontal cross-member bodywork section gave the car a softer nose.Although a new design, the carry-over of previous components and the blending of techniques meant that the Ami was a sort of semi-monocoque, platform-based car.

The 2CV’s leading/trailing arm long travel suspension with torsion-bar damping and independent function gave the car superb ride quality and a ‘loping’ feel that could eat up distances; however, the high roll angles persisted – but so too did tenacious grip and typical front-drive understeer. In a strange and typically Citroën paradox, we can see that the original Ami was a ‘Berline’: a saloon car with a boot, yet it later became a fastbacked saloon and a true estate.

Citroën’s managing director Pierre Bercot had authorized the study of a flat-four engine of around 1.0 litre, but neither that idea nor a Panhard small engine of approximately 850cc were deemed suitable. So Citroën simply bored out the existing 2CV twin-pot of 425cc (itself uprated from its original 375cc), and created the 602cc version found in the first Ami 6 Berline with its 22bhp.

The Ami 6 Berline stayed in production from 1961 to 1968. Thereafter it was subjected to some degree of ‘normalization’ – perhaps a contradiction to the Citroën purist, but certainly a rationalization to increase sales and decrease costs.

For the 1962 model year upgrades were made to the Ami 6, notably changes to the rear window opening function to make them slide. Various trim and specification changes took place in the 1960s, including some wonderful two-tone colour combinations. The reality was, even with the Ami 6 advertising and specifications aimed at female buyers, the car lagged well behind the 2CV and its enduring minimalist appeal – even in 1963, the 2CV was outselling the Ami 6 by a ratio of nearly two to one. The Ami 6 was over one third more expensive to purchase than a 2CV, yet it had the same engine as the larger capacity 2CV models. It was a case of another Citroën paradox: however, the Ami would come into its own.

Citroën’s idea for a mid-range car had slowed at the altar of engine power and body practicality. The answer was to fit bigger engines and add a pretty fastbacked body and a proper estate-car variant. Heuliez suggested the first Ami estate or ‘Break’, and kept the existing rear side doors; but Citroën rejected this and created a more radical re-tooling for the eventual estate bodyshell.

Front and rear views of the Ami 8 in contrast to the car’s 2CV ancestor seen in ‘Spot’ special edition mode.

Triangulated rear side windows were a design theme at Citroën long before the GS and CX.

So were born the Ami 8 and ultimately the Ami Super, a car with nearly 60bhp – nearly three times the horsepower of the Ami 6 Berline of 1961, and almost twice that of the Ami 8. With added sound proofing, better trim, less bare metal in the cabin and the GS-type 1015cc engine, not to mention a floor-mounted gear shift, the Ami Super more than lived up to its name in comfort and in its peppy performance and overtaking ability. The British loved the Ami Super and its power-in-a-light-body theory of an early ‘hot hatch’ capable of 87mph (140km/h) – or even 95mph (153km/h) downhill with a tailwind!

For the 1970s, a plastic interior was fitted.

Bright blue Ami Super hot hatch!

Saloon and estate seen together capture the Citroën atmosphere.

The rare Ami 8 van and the Super service van ought really to have a cult following, but few examples remain of this stealthy Citroën. Even rarer are the North American Ami. A few Berline cars were imported into North America from 1963 to 1965, with a very few later Ami Breaks rumoured in 1968.

MODEL DEVELOPMENTS

1961: Ami 6 Berline launched.

Autumn 1961–1962: Model year cars with revisions, notably opening rear windows.

Ami fanatics!

Under the bonnet, the forward-biased engine location is obvious.

1968: Ami 6 Berline terminated. One bodyshell used for M35 engine and suspension development.

1968: Ami 8 saloon launched, featuring new front styling and completely new rear end with sloping rear windscreen and triangulated rear side windows as ‘six-light’ styling. Vertically tailed, ‘Brake’ or estate version also soon launched (1969), both cars with larger 32bhp engine. Front disc brakes installed.

1973: Ami ‘Super’ launched with much larger 1015cc flat-four ‘boxer’ engine, revised plastic-moulded facia and fittings. Significant under-bonnet tooling changes were required for the fitment of the horizontally opposed engine taken from the lower-powered Citroën GS range. Gearbox and gearshift actuation changes were also specific to this larger-engined car. The Super and the Break used wider-section tyres of 135 15 ZX ratio, compared to the Ami 8 saloon which retained the 125/15 ratio. Trim levels were Luxe, Confort and Club. Difference in seat type and trim were the most obvious trim variations. Club models had individually reclining seats.

1974: Thicker rear anti-roll bars to reduce roll; fog lamps fitted; use of vinyl side stripes for some markets.

1976–78: Continuing trim changes and ‘run-out’ specifications, including vinyl stripes and seat trim changes. Production of Ami Super ceases in 1979.

America: In 1963 low numbers were exported to the North American market; these featured added chromework, bumper bars and turn indicators to meet legislation.

Spain: The Ami 6 and Ami 8 were also built by Citroën Hispania in Vigo, Spain, as the 3CV and C8 (not the Ami) from 1967 to 1978. The name ‘Familiar’ and C-8 were used in Spain, not ‘Ami’.

Argentina: The Ami 8 was manufactured in Argentina until 1978. The estate version was exported to Uruguay and Paraguay, and to Chile as a CKD kit (see below)

Chile: The Ami estate was built up at a CKD assembly plant in Arica, Chile, from late 1975 to 1978, when, amazingly, the complex CX was built from CKD kits as a prestige Chilean market offering.

Vans

Ami service vans were rare; even rarer was the glazed ‘Vitre’.

Total production of the Ami models (except the M35) reached 1,840,121 units, of which 722,000 were the Ami Super, according to Citroën figures.

‘OPERATION M 35’: A SINGLE ROTOR FASTBACK AMI

Fascination with Felix Wankel’s rotary-cycle engine had been around for decades. Unlike a normal piston-cycle engine where the intake, compression, combustion and exhaust all take place within the same space, the Wankel offers separate chambers for such functions and provides a continuously functioning, gas-flowed path in the cycle from chamber to chamber. The cycle is of a rotating or radial action rotor (as a piston) that passes around a main housing containing the relevant chambers, and allows separate efficiencies, as compared to a standard cylinder head and piston design where everything takes place separately and in the same space. In the rotary engine the piston action process is continuously driven.

People talk of the ‘turbine smoothness’ of the Wankel engine, but this is a misnomer as the Wankel is not related to the jet turbine because it is an internally driven combustion engine, not an external one like the jet turbine function. It does function as in the gas-flowed sense of the gas turbine, but not with blades: with the conventional engine’s pistons replaced by rotors in chambers, the Wankel is much smoother in its function and power/torque delivery, and lacks chattering valves and shafts.

The claim is often made that Citroën’s first investigations into rotary-cycle engine technology were in the 1960s, but this is incorrect because in 1938 Citroën sponsored the building of an orbital rotary-cycle engine to a patented design by Dimitri Sensaud de Lavaud, who designed a five-lobe outer rotor that possessed an inner hypocycloid motion allied to an inner rotor of six lobes with a 5:6 reduction ration. This single prototype engine was built by Ateliers de Batignolles under the French Air Ministry from 1939 onwards, but was abandoned in 1941 due to a number of issues and war-time perspectives.

Post-World War II, investigations into numerous engine cycle ideas led to the further development of the Wankel engine in Germany, Japan and in America, notably at NSU, Mercedes, Mazda, Suzuki and Curtiss-Wright/GM. With impending emissions, safety and other legislation, it was deemed that the Wankel engine had a future. Of interest, the Wankel engine is much smaller and lighter than a normal piston-cycle engine, and offers the engineer and designer the chance to build a car with a lower centre of gravity to benefit handling, and a lower frontal styling line to benefit aerodynamics and visibility.

These were the reasons Citroën became interested in the Wankel engine in the early 1960s. After preliminary talks in 1962–63, in 1964, at the primary instigation of its lead engineer at the time, Jacques Nougarou, Citroën entered into a partnership with the main Wankel design development licence holder of Neckarsulmer Stricken Union (NSU) in Germany; the result was the Société d’Étude Comotor company in June 1964, which was a joint project to study a small, rotating Wankel cycle engine.

The rear side window design is a precursor to that for the GS and CX, and surely weakens the claims made by some about the influence of the Pininfarina Aerodinamica cars on the GS and CX styling?

By March 1965 the joint venture began as Comotor Société Anonyme, with a capitalization of $300,000 US dollars. In May 1967 this had resulted in the Compagnie Européenne de Construction de Moteurs Automobiles (Comotor SA), capitalized at $1,000,000 US dollars (registered in Luxembourg) for the production of a smaller, single rotor engine for use in a Citroën ‘M 35’ car. Comotor was housed in a small factory in West Germany. Citroën created its own laboratory, headed by Michel Audinet, which led to the single and bi-rotor Citroëns. The chief engineer across all Citroën engine development at this time was André de Bladis. The engine was to be manufactured by Audi-NSU/VW and transported to France for installation in the car. On start-up in 1970, Comotor was funded to the tune of $4,040,000 US dollars.

Developed from 1967 through to launch in 1969, NSU and Citroën created an engine that was actually more advanced than the engine in the NSU R0 80. (Of interest, the new Citroën engine replaced chrome in its working surfaces with a nickel-silicon alloy.) In order to cure cracking around the sparking plug portal, a copper housing around the plug was designed. Stronger tip seals than those used in the RO 80 or Prinz cured the tip seal issues that affected those cars’ engines, and achieved a significant reduction in engine working temperature.

Citroën and NSU were at the leading edge of Wankel developments11, and the news that General Motors had paid Audi-NSU/VW 50,000,000 US dollars in 1970 to buy Wankel licences shows just how advanced the Wankel idea had travelled. Citroën’s investment was looking like a wise move if GM were considering a range of Wankel-powered cars. The Toyo Kogyo Matsuda-owned company – Mazda – were also racing ahead with Wankel engine development (and still are to this day).

In a move that encapsulated the Citroën thinking of the time (SM, GS and CX were all in their complicated developments in this period), Citroën decided to build up to 500 specially bodied cars based on the Ami, and to let chosen special customers in France buy them (at nearly the cost of a DS) as officially sanctioned public research vehicles via the official dealer network. In a strange paradox, Citroën effectively ‘sold’ a non-production model that in theory was never mass produced nor offered ‘for sale’ in the traditional sense. As an engineering research exercise it seems a bizarre and costly affair, and yet was one that gave us the now revered M 35.

Using an Ami floorpan and front under-skin structure, M 35 had a special lozenge-shaped, fastback body with triangulated rear side windows that were a precursor to such shapes in the GS and CX. Styled by Opron’s team and significantly Giret and Harmand, the M 35 was a two-door small coupé of immense appeal to the younger Citroëniste, and many think that even if fitted with the GS flat-four engine as used in the Ami Super, as opposed to the Wankel unit, the car would have sold very well for Citroën in the early 1970s. Because the engine needed to be placed well forward, the front body metal was elongated in a hand-built nose cone, and is not a standard Ami pressing.

Heuliez were part of the car’s original design and development in body engineering terms, and they built the car up as a full body and then shipped it to Rennes la Janais in Brittany for engine and drivetrain installation and trimming by Citroën. Heuliez chairman Henri Heuliez drove an M 35 for years, and travelled over 50,000 miles (80,000km) in his specially painted, blue M 35.

Some writers claim that the M 35 was pure Ami in structural terms ahead of the B-pillars, but this is incorrect as M 35 had a faster-raked windscreen and A-pillars of greater length (with resultant modifications to the bulkhead metal), and this required a new, larger windscreen of greater height; glass was specially made in low numbers for the project.

The leather-trimmed front seats pre-dated the similar SM seat design by incorporating a reclining backrest that pivoted not at its base, but at the lumbar region. Many of the trim items came from the DS.

Citroën planned to build 500, but the numbering system and odd and even number usage has led to confusion. Were 473, as numbered, built? The answer is no, 473 were not built even if the inaccurate wing-mounted number on the final car is ‘473’. And where are they now? The biggest M 35 enthusiasts remain the Dutch and many are owned in the Netherlands – one garage has stored over twenty M 35s. The records state that Citroën built 267 M 35s, well short of the advertised 500. The first M 35s were built in 1969, 212 were built in 1970, and forty-nine in 1971, with the last car numbered as 473 being sold on 12 March 1971. Today it is believed that fewer than eighty cars survive.

Like the Ami, the gearshift was a facia-mounted device of convoluted design. However, three cars were built with the later Ami Super-type floor-mounted gearshift – these cars were painted in a metallic blue rather than the sable grey metallic of the other M 35s. One of these cars was reputedly fitted with the GS-type ‘Convertisser’ automatic transmission; the only known ‘blue’ car was no. 39, which resided in the Heuliez collection until the entire collection was sold off in 2012.

Of particular note, the M 35 used the DS-style hydropneumatic suspension system, but in modified form. This meant that M 35 had its suspension spheres placed not above the wheel as de facto strut length, but as a horizontally linked trailing/leading arm connected to a more centrally mounted hydropneumatic springing system. Despite the nose-heavy engine mounting, understeer is not excessive and the super-smooth ride and sleek bodywork give the car a real coupé air.

The single rotor engine had smooth power from below 2,000rpm. Noise from the engine and specially modified GS gearbox was minimal, and other niceties included aerodynamically vented, inboard-mounted, powered disc brakes at the front. The test mule for the 35 single-rotor engine was an Ami 6 Berline, which was fitted with the Wankel unit in 1968 and extensively run at Monthléry. In the M 35 a rev-limiter warning buzzer went off at 7,000rpm to warn the driver to ease off or change gear, but even with this, some engines expired at low mileages. A tachometer was wisely added in the cabin as a ‘stick on’ item on the facia. Problems with the spark plugs (two) were soon solved, and any M 35 driver who got stuck with his plugs could always borrow some from an NSU Spider or Prinz!

Clearly, with its upgraded engineering, specially designed and built body, luxury cabin trim, and build run of the intended 500 units, M 35 was an expensive and questionable way of conducting research. If the 1970s economic crisis had not struck, Citroën may have actually mass produced a version of the M 35 – with or without the Wankel engine. If only even a flat-four GS engine from the Ami Super could have been used in the M 35, Citroën enthusiasts would have had yet another wonderful 1970s Citroën to saviour. But it was not to be in any sense, and today M 35 represents both a lost ‘moment’ and a true classic car. It also paved the way for the twin rotor Wankel engine in the equally abortive GS ‘Birotor’ project, and the early work on a triple rotor engine that was abandoned. In 2011 one M 35 owner did indeed fit a GS engine to an M 35, and others may do likewise – at the risk of offending M 35 purists.

M 35 Today

What happened to the M 35s that were let out into arranged ownership? Given the fragility of the rotor tip seals and the special ‘prototype’ bodies, Citroën tried to get them back from the public test customers and the dealers who had taken them, but in France and the Netherlands, many M 35s ‘escaped’ and remain in private hands to this day; they are perhaps one of the rarest of all Citroëns.

Citroën had entitled the M 35 project ‘Operation M 35’. Today as M 35 fanatics search out the remaining cars, a Dutch collector and his associates have brought many of them together (plus or minus twenty-three cars) and launched a new Operation M 35 – ‘La Nouvelle Operation M 35’. Sander Aalderink is the man at Eenden Garage in Womer, the Netherlands, who fronts the wonderful M 35 ‘rescue’ programme. It has now been decided to allow the sale of some of the M 35s in the collection. Sander’s records show that there are even M 35s that made it as far as Texas, Canada and Australia.

All these years on, for some Citroënistes (the author included), the Wankel-powered M 35 coupé provides a tantalizing example of pure Citroën intelligence on a scale so typical of the men of the Bureau d’Études. M 35 is a wonderful yet forgotten example of the essence of Citroën.

SPECIFICATIONS |

1970 YEAR CITROËN M 35 |

Body construction

Platform frame with semi-monocoque welded bodyshell

Engine

Type |

Wankel single rotor |

Chamber displacement |

30.03 cubic inches (497.5cc) |

Equivalent total displacement |

60.6 cubic inches (995cc) |

Compression ratio |

9:1 |

Power |

49bhp at 5,500rpm (55bhp claimed in some references) |

Torque |

50.6ft/lbs at 2,745 rpm |

Carburation |

One two-barrel Solex 18/32 HHD |

Ignition |

Coil |

Cooling |

Water |

Clutch |

Single dry plate |

Transmission

Type |

Four-speed manual |

Suspension and steering

Suspension |

Front single leading arm on each side, with hydro-pneumatic sphere springing with anti-roll bar. Rear suspension trailing arms on each side with hydro-pneumatic sphere springing with anti-roll bar |

Steering |

Rack-and-pinion type |

Brakes

Power assisted. Inboard discs at front of 10.65in diameter: rear drums of 7.12in diameter

Tyres

Specially adapted Michelin X 135-15 radials with finer-mesh belting and differing compound

Dimensions

Wheelbase |

94.5in (2,400mm) |

Front track |

49.6in (1,260mm) |

Rear track |

48.03in (1,220mm) |

Overall length |

159in (4,039mm) |

Width |

61.25in (1,556mm) |

Height |

53.25in (1,353mm) |

Performance

0–50mph |

12sec |

0–60mph |

16sec |

Top speed |

89.5mph (144km/h) (fourth gear) |

Fuel consumption |

24.5mpg (11.5ltr/100km) (average) |

So smart: note the rear bootlid airflow management pressings. Even if it had been fitted with a GS engine, surely this would have made a stunning 1970s Citroën coupé? What a waste...

DYANE – THE DELIGHT

When Renault finally grasped the front-wheel-drive concept and produced the Renault 4 in 1961, it was a compliment to the 2CV idea that the Renault 4 mimicked it. However, the Renault 4 was far more than just a copy of a 2CV: it was an updated, more modern, slightly more comfortable car far more in tune with the 1960s than the austere and abstract 2CV. As such, the Renault 4 created stiff competition for the 2CV, and Pierre Bercot at Citroën immediately realized that the 2CV might be in trouble. Could Citroën reverse engineer the Renault idea into an upgraded Citroën 2CV?

Yet with Citroën just about to launch the Ami, had that not in some context been achieved? In reality, however, there was still a gap between the Ami and the 2CV, and the Ami was bigger than the Renault 4. From these events stemmed the idea of updating the 2CV, yet retaining the essential basic appeal of the concept. But the Ami was a saloon (at that stage), whereas the Dyane was a proper hatchback.

A blue Dyane 6 hastens through rural Brittany: original and in daily use, this is a Dyane that kept going.

Dyane delight on the move. Another lovely Dyane shows off the integrated elegance of its cute early ‘eco’ car design credentials. Note the concave side panel sculpture and its resultant tension and clean lined form.

Dyane Design

Citroën at this time was hard pressed for resources and capacity, as the revisions to the DS, and new projects, were stretching it to the full. Of relevance, Citroën had since 1953 had a close hand on Panhard, purchasing 25 per cent of the marque in 1955 and the remaining share in 1964. It was obvious that Panhard could add to the resources needed to create a modernized version of the 2CV.

So it was that Panhard and its designer Louis Bionier were asked to create the new idea – the car that would become the Dyane. Behind Bionier’s headlined name there lay the now forgotten and uncredited work of the designer René Ducassou-Pehau, from Basque country. Much of the design development work and themes for the Panhard-Citroën that became the Dyane stemmed from René Ducassou-Pehau, and also from assistant designer André Jouan. In 1961 Ducassou-Pehau also created a design for a floating, non-rotating steering hub containing essential driver information and aids; such an idea appeared on the 2004 Citroën C4. René Ducassou, as he is sometimes known, was also a key part of the design of the Panhard range before the company closed.

By 1965 Panhard had presented its sketches and models of the proposed car, with some changes being made by Citroën at Bercot’s request. In the Bureau d’Études Henri Dargent was by now established, and it was he who suggested themes for the new car’s interior (re-used in the later revised Ami range). Jacques Charreton, who contributed to the revisions to the exterior as well as Dargent, wanted modern square headlamps, but the cost-cutters at Citroën put 2CV round headlamps in chromed, square housings – which must have been just as expensive as plain square lamps on their own!

Despite having several fathers, the styling of the Dyane was taught, elegant and utterly original, and not as easily dated as the 2CV’s abstract form. Some say the taught, concave door skins came from Bertoni’s mind prior to his death in 1964; others attribute them to Panhard’s men.

Possibly originally planned as a separate Panhard-Citroën creation with its own chassis or monocoque, and originally presented in prototype form with a Panhard grille and badging, the Dyane was soon to be based on the existing 2CV platform and components – a huge saving in time and money for Citroën, even if it did not lead to the car as originally suggested.

Dyane used the 2CV’s 425cc engine and then the 435cc version, but by late 1968 it was a Dyane 6 with the 602cc-type air-cooled twin-pot engine with its higher compression and forced induction system. The Dyane could also have the ‘Traffi-Clutch’ (also fitted to the Bijou), which was an early form of centrifugal slip device to reduce wear in urban use.

The suspension was the long travel, independent, interconnected torsion-bar system from the 2CV, which gave the expected ride quality via the linked bars and arms on each (lengthways) side of the car. The Dyane boasted its own body structure and interior, as well as dedicated trim items; only in engine and floor punt was it a 2CV derivative.

The Dyane 435cc had a top speed of 68mph (109km/h), but it could be coaxed to 70mph (113km/h) quite easily, especially if well maintained and not suffering from worn spark plugs or a carbon-clogged head. The Dyane 6 claimed a top speed of 75mph (120km/h), but Sir Douglas Bader said his Dyane 6 (with tyres over inflated) could ‘Easily get to eighty, old boy’ – though he may have used high octane fuel, and he certainly turned his door mirrors inwards to reduce drag.

The name ‘Dyane’ is said to have stemmed from Panhard’s internal code name (their cars had had a DY prefix), yet some people claim that the use of a ‘D’ prefix stemmed from Citroën’s marketing men, who wanted to link the new small car to the DS and its Greek goddess derivations. Given the 1967 launch of the revised ‘slant-eyes’ DS and the 1967 launch of the Dyane 4, the marketing men may well have been correct.

Using the 2CV chassis platform, 2CV engines and a myriad of fittings, the Dyane was cost effective and appealing to customers young and old.

The Dyane was indeed an economy car, yet an elegant one, and with smoother style and more practicality than a 2CV it should have eclipsed the venerable 2CV – yet strangely it did not, and the 2CV outlived the Dyane. Yet the Dyane was a delight to drive – a ‘peppy’ little car with ‘point and shoot’ steering, a great ride and handling ability, and the combination of a useful hatchback, a roll-back sunroof, and 50mpg (5.6ltr/100km) economy. The Dyane was well finished and comfortable, and only in terms of performance and passive safety was it of its time – and otherwise, wasn’t it a precursor of today’s ‘eco’ car?

The Dyane 4, Dyane 6 and the Acadiene van (and Four-gonnettes) racked up sales figures of over 1 million, at 1,444,583 units sold from 1967 to 1987 (van production continued for nearly three more years after the late 1983 cessation of the standard bodyshell).

DYANE DETAILS |

1967–69: Dyane 4 with 425cc, 21bhp at 5,500rpm, and 435cc, 28bhp at 6,750rpm. Top speed: 64mph (103km/h).

1969–84: Dyane 6 with 602cc, 28bhp, then 32bhp at 5, 570rpm. Top speed: 75mph (120km/h)

1970 : Six-light body with extra side windows in the C-pillars.

1978: Dyane Acadiane replace the 2CV-based AK400 as Citroën’s light van, with the old AK400 rear body mated to the Dyane at the B-pillars. In production until summer 1987.

Overseas production: Dyane production took place in Argentina, Iran (as the Jiane), Spain, and in Slovenia (then Yugoslavia) by the then Tomos company.

Several Special Editions were created, the most numerous being the 1,500 examples of the Dyane Cabane, the 600 Dyane Capra, and 750 Edelweiss that were built in Spain. Edelweiss had blue paintwork, front and rear bull bars, and wind-down windows. The Dyane Weekend was widely popular across northern Europe.

Late model Dyane in rare metallic paint looking very stylish indeed.