The 2013 Cactus Concept hints at a new model design from Citroën. Note the newly revised chevron motif and DS-inspired ‘floating’ roof and stylized C-pillar. All pointers to a new shape for a new model expected onto the market in 2014.

CITROËN: A DESIGN PHILOSOPHY THAT CREATED CARS

Why are Citroëns designed as they are? Surely despite all the claims, Citroëns are just cars like any others? The answers to such questions are that Citroën design is unique, and no, the Citroën is not just a car like any other.

There are other questions about the why and how, and not just the when of Citroën. What does ‘old Citroën’ now mean, what mental picture does the phrase engender? Once it meant a Traction Avant, and to a wider audience it means a DS or 2CV, but to some, ‘old Citroën’ might now mean something else entirely. Beyond the world of the DS and 2CV there is a whole new generation of Citroën enthusiasts who have little experience of these icons: Citroënism to such people means a CX, GS, BX, XM or C6 or DS3. So would it not be better if Citroënism also meant the more recent cars, as well as the cars from Citroën’s deeper past?

Some Citroën enthusiasts dismiss so-called ‘lesser’ Citroëns, and a few are contemptuous of anything produced after the Peugeot takeover of Citroën. Yet surely Citroëns are not just classic cars – they are new, current production cars, too. Therefore, amidst many books on the marque, this text is an attempt to reframe a sometimes tribal debate amid Citroënistes and to provide a new reference point for a wider readership who, like me, are fascinated as to the why of Citroën – old or new.

Citroën has been the subject of many words, but some commentators have followed the fashion to see certain examples of the Citroën marque in isolation, however splendid. Could it be that a differing analysis might reveal new or obscured strands of the Citroën helix? Creating a book that crosses boundaries and tries to blend various aspects of Citroënism is not easy, but herein is an attempt to weave history with the ‘atmosphere’ of Citroën. The reader seeking every single production, ownership, or restoration detail of a specific Citroën model will need to consult the individual books that cater solely for each model respectively. Herein, the narrative highlights key design aspects, their causes and effects, and the creators of such facets of the cars.

The Citroëniste must ask difficult questions. For example, will the gorgeously sculpted C6 of circa 2005–2012 become a ‘classic’ in years to come? Perhaps it could, and maybe it is just a matter of time and patination: imagine, if you will, a young enthusiast dreaming of restoring a faded, down-on-its-suspension stops, flaky old C6 found in a barn in 2030. What joy might that engender in the mind of a future not yet cast – and would that young enthusiast, discoverer of a curved behemoth of a barn find, ever wonder what made the car what it was? He or she would have to look backwards, not just to the DS, but far back into a magical age of metal bashing and sculpted carrosserie to understand the ethos of Citroën.

The legend. As fitted to British-built 2CVs.

Citroën’s early rear-wheel-drive exploits, and the aeronautical and engineering tutelage of the 1920s that so crucially informed it, and its resultant ethos, are less commonly subjected to discussion. Such vital ingredients of the story are also rarely considered in relevance to the more contemporary Citroën cars. The fact is that without these early events, the revolutionary Traction Avant, the DS and all that flowed therefrom, could not have occurred: yet the relevance of early aviation, and the role of French education, architecture and design in Citroën’s history, are often obscured by more modern and apparently ‘iconic’ Citroëns amidst writers’ stories of them.

Perhaps a wider perspective can lead us to realize that today’s Citroën, and the Citroën of distant decades ago, are undeniably linked by a founding ethos that is still manifested in the now. Citroën’s current designers have recently begun to remind us of the marque’s aeronautical heritage through the new DS-line cars, especially the DS5. Architectural influences are also now deemed relevant to today’s Citroën design, just as they were eight decades ago when the likes of Le Corbusier inspired design. Architecture seems to be a strong theme in the lives of Citroën stylists and their training, and even today the names of Gropius, Wright, van der Rohe and Hadid are cited by Citroën designers. And fine art – from Chagall, Kandinsky, to the impressionists and to Picasso and beyond – is also relevant to what happened at Citroën. Frédéric Soubirou, the new DS5’s body designer, recently said:

We’ve been inspired by our past and aviation, but also by the rest of the automotive industry. A few years ago this was a UFO, we had no experience on this, we wanted a new story for the DS, we wanted heritage. The DS should be recognizable from a distance, but it has to be consistent with the entire line. It is an architectural object1.

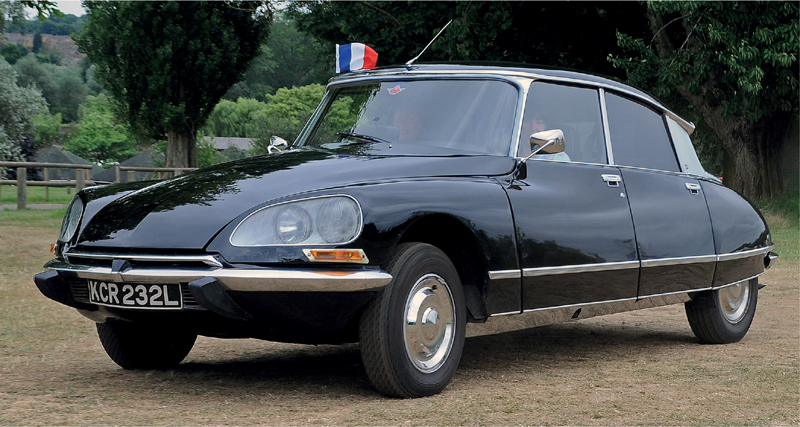

DS design on the move. A late model DS in black flies the French flag in an evocation of the atmosphere of Citroën and Bertoni, as its double-lobed ellipsoid styling makes its definitive statement.

Such words prove that a resurgence of the origins of the early ethos is upon us at the same time that this book is written, with its own examination of that very genesis.

Because the key to Citroën’s identity is design led, this book has a design focus – how can it not, for it can be argued that industrial design as we know it stemmed in part from André Citroën’s actions as a founding father of the motor car and in the design innovations of his cars.

Those brilliant Citroënistes the Dutch, with their love affair for Citroën, enthuse about all types of Citroëns old and new – but it seems that based on certain other interpretations you could be forgiven for thinking that the rear-wheel-drive world of Citroën before 1934 had little to do with the subsequent front-wheel-drive cars. Other opinions seem to suggest that life begins and ends with the DS, or that the last ‘real’ Citroën was built prior to 1976 upon the Peugeot involvement.

Yet the reality is that today’s Citroën is one grown from the earlier foundations of its DNA as the soul of Citroën engineering and design. From 1919 to the current reincarnation of the ‘DS’ branding, the spirit of Citroën has never died – it may have faded for a time, but the essence of Citroën is unbroken. And while the DS – ‘La Déesse’ (the Goddess) – may be famous, there was advanced Citroënism both before and after the DS, something a few Citroën commentators sometimes forget.

A rare, red SM gets going. The SM’s six Cibie headlamps under a glass fairing still astounds today’s observers.

If the DS frames an image of Citroën, as it quite rightly does, then we should not be blinkered by its halo, because other wonderful Citroëns exist, both old and new, and good as the DS is, Citroën as a marque is about something wider. This is a statement that will infuriate those who inhabit the DS ‘cocoon’, but there is a balancing to be asserted. However, be under no illusion, for the DS was, and remains, a defining event in automotive history – maybe even in history itself. But the complexity of Citroënism and its construction does embrace a bigger picture.

Conversely, neither is Citroën solely about the 2CV – which really ought to be the ‘Deudeuche’ as it is known in colloquial French by those who love it.

Without the earlier experiences of 1919 to 1933, André Citroën, his company, and the men he drew to him to create all the subsequent cars, could never have become what they later became. The Citroën design ‘dream team’ amidst the Bureau d’Etudes did not just occur overnight: it took years of growth and learning amidst a rare tutelage. Was the Citroën philosophy, the unique ethos, solely of André’s hand? The answer is no, for it stemmed both from him and others: André’s dynamism created the story, but others fuelled the plot.

In terms of his own psyche and actions, there was indeed something unusual about André Citroën’s shaping of his company and its cars. He seems to have part created, part landed upon a maverick marketing or branding profile that was an early example of the unique selling point, and a niche identity that most other mass car makers often failed to achieve. Amidst the great landscape around this very clever man, his incredible energy and open-minded attitude, there can be found a substrata of men and deeds who themselves were vital to the cars that resulted. And these men were cast into a time and place in history and society that was unique.

While not in any way undermining the genius of André Citroën as the true hero of the marque, the fact remains that his cars were designed and detailed by other men when he was alive, and after he was dead. Such men may well have been responding to André’s innovative, maverick future vision and his determination, but nevertheless, it is they who actually thought out the cars and the specific engineering and design features. After André’s demise, his ethos and that of his team carried on and seeded a future cast upon the wings of the wind – wind being a key Citroën element.

So it is clear that while some Citroënistes see André as the sole cause and effect of Citroën, this cannot be wholly accurate. And some say that André Lefebvre, as Citroën’s first great design pioneer, was in some sense the protégé or pupil of André Citroën. But the two Andrés, Citroën and Lefebvre, only worked together for under three years before Citroën’s early death, whereas Lefebvre had come to Citroën after more than a decade of creating experimentation and innovation for Gabriel Voisin amidst an explosion of knowledge. Lefebvre and his colleagues were all the product of an amazing era in French engineering, design, art, architecture and philosophy that they were born into, educated within, and emerged from.

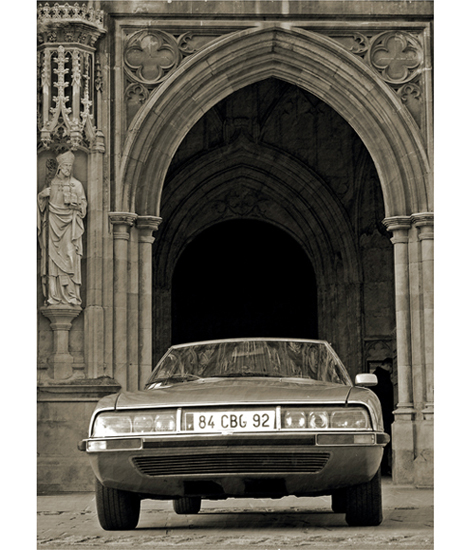

Citroën and architecture have long-established links. Here the SM sits under the entrance to Gloucester Cathedral.

Any reader who doubts the effect upon Citroën of Gabriel Voisin as claimed in this book, needs to investigate just how many of the men of Citroën and its Bureau d’Etudes had come through the French colleges (notably as ‘Ingenieurs Arts le Metiers’) and then worked for, or near Voisin in his aviation arena after graduation and before finding their way to André Citroën’s employment. Even a later President of Citroën, Robert Puiseux, had worked for Voisin. Again, today many of Citroën’s designers have an interest in aerospace technology and architecture.

The role of the grand engineering schools and design institutions of France – the École des Arts le Metiers, the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, the École des Beaux Arts, the École Grande Polytechnique, and the École Nationale Suprieure de l’Aeronautique et de Construction Mecanique (Sup’aéro) – play a significant yet rarely credited role in Citroën’s development as a company. Nearly all the men of Citroën from 1920 to 1970 had graduated from the education of these great colleges.

Today, Citroën’s engineers and designers come from such schools and their modern equivalents such as the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Appliqués et des Métiers d’Art, the Insitut Supérieur de Design, the École Superieure d’Arts Graphiques et Architecture Interieur et Design, and of course, from the Royal College of Art’s Vehicle Design Unit, the Los Angeles Art Centre Car Body Design Unit, and a small and select band of transportation design courses at various colleges in places such as Lyon, Coventry, Detroit, Turin, Milan, Zurich, and Stuttgart.

Amid all this education, France in the early years of the twentieth century saw the birth of world famous artistic and intellectual movements. André Citroën and his men were witness to the techniques and effects of everything from Impressionism, Cubism, Art Nouveaux, Art Deco, Modernism and the streamlining movement, to the philosophy and science of France’s greatest period of intellectualism and open-minded innovation. France circa 1900 to 1930 was the centre of an explosion of artistic, architectural, engineering, medical and social revolution. Other nationalities and their efforts were for some time eclipsed by the incredible multi-disciplinary talents of the French. Many great advances that touched the world came from France at this time. And there was a reason why Wilbur and OrvilleWright went to stay in France – at the heart of early aviation.

How many people know that Citroën (at Pierre Boulanger’s lead) funded the pioneer aviator Sensaud de Lavaud in the 1930s, to develop not just his gearbox ideas, but also his now long-forgotten rotary-cycle engine, and encouraged diesel engine development by de Lavaud. This was decades before others leapt aboard the ‘rotary’ bandwagon, which Citroën re-joined in 1964 to explore Wankel-cycle technology. And Citroën’s first diesel-powered vehicles were pre-World War II.

Given all the advanced thinking evident, it becomes clear that Citroënism does not begin with front-wheel-drive cars: it is the earlier developments of Citroën via its early history amidst the aeronautical innovations of the 1920s that led to the front drive, aerodynamic, ingenious ethos that so encapsulates Citroënism today. Citroën and Citroënism is all about thinking and doing the previously-assumed-to-be-impossible – or achieving the not-even-thought-about: Citroën is daring, different and brave, just like André Citroën its founder, and his men.

A 1927 C-Type displays the earlier version of the Citroën corporate branding. This car spent much of its life in Australia before arriving in Great Britain.

THE ELEMENTS OF ALCHEMY – VOITURE AERODYNAMIQUE

What is the act of studying aerodynamics: is it an aeromancy? The dictionary says that ‘aeromancy’ is ‘divination conducted by interpreting atmospheric conditions’; how apt, then, for Citroën’s famed aerodynamicists that such study and use of the wind should be a lead strand in the DNA of Citroën. As Citroën stated in 1984:

Aerodynamics – recently this facet of the motor car has received much attention. Citroën has been building aerodynamic body shapes for production cars of increasing and tested aerodynamic efficiency since 1934. Citroën is now responsible for an entire marquee, which, in genuine realistic terms of total drag and aerodynamic efficiency, is superior to any rival, class by class.

Was this extravagant engineering taken to the edge of complicated confusion – or entirely rational genius stemming from superior IQ?

The Details of Design Research

There are only so many ways you can say the same thing, whoever the author might be, but what of a new analysis? Does the known story of Citroën support a more extensive automotive archaeology?

The answer is a resounding yes, for having studied the well recognized and profound effect of Gabriel Voisin upon André Lefebvre (and then the influence on Citroën of Pierre Jules Boulanger), it was correct to go deeper still because it is unlikely that Lefebvre, Voisin, Cayla, Mages or Boulanger assumed anything from perceived evidence. It is clear that they avoided this dangerous practice, and instead thought new thoughts, and that this design research psychology or philosophy underpins Citroën. And the revelation that Voisin luminary Pierre Cayla had invented not just aeroplanes, but an oleo-pnuematic self-regulating braking system for cars, and that Jacques Gerin had created an ‘Aerodyne’ that was a precursor to the DS, should both be food for thought.

CX elegance. The Opron-designed styling elements reek of an elemental Citroën leitmotif in this CX Prestige. A piece of ‘perfect’ design, restored by James Walshe.

We Citroënistes may well suffer from OCD, or ‘Obsessive Citroën Disorder’, or a Citroën psychosis. Perhaps it should be called Citroënitis, for it is a strange condition whose symptoms include staring at your Citroën from the kitchen or living room window, or worse, the bedroom (but not if you are French!). Those with Citroënitis are very protective about their cars. Maybe one can even be a Citroholic? No recovery programme is known.

I have owned many Citroëns: some have frustrated me with their foibles, but all have charmed me with their characters. Many Citroënistes have a passion for old Saabs and often refer to them as ‘those Swedish Citroëns’. Few people know that in 1973 Citroën designed and built a 180bhp Wankel rotary cycle-engined helicopter, and subcontracted Saab to help build it. The helicopter, which had alloy blades, flew 200 hours test flying before the economic crisis of the 1970s and Citroën’s debts effectively killed it.

Having been brought up from early childhood with my grandfather’s Slough-built Citroën DS, I can be forgiven for my first car being a Citroën GS (accompanied by a Saab 99), and then a GSA, CX, Visa, ZX, and more recently a BX restoration project that resulted in a ‘daily driver’ for over a year. My GS derivative, the GSA, was a perfect car, totally reliable and strangely rust free. Today, motoring writers effuse about Subaru’s flat-four horizontally opposed engines – yet Citroën has been designing them for decades.

Behind the Wheel

Driving a Citroën gives one a range of feelings. On starting up a hydro-pneumatic Citroën, one hears a gurgling and belching of the oleo-pneumatics as the mineral mix oozes through the many metres of pipework that course around the car carrying the fluid to its function. Then there is a clicking from behind the bulkhead as the suspension pump energizes as the engine revs rise, and suddenly the car levitates and there is a gushing sound of oil in pipework. This borborygmus rumbling of gas and oil in the car’s intestines signals that the system is ready. Such is the Citroën, a wonderfully tactile, rewarding experience like no other.

What of the joy of driving and owning the twin-pot Visa? Whatever its ‘humble’ Peugeot origins, which might offend certain Citroën purists, this car was a superb device. My blue Visa was, with its pin-sharp steering, expertly tuned with conventional suspension, and brilliant body and cabin design, a real highlight, all without hydro-pneumatics. What a car, and a small, cheap one at that; for those in the know, and those who are not Citroën elitists, the Visa in 2- and 4-cylinder forms was one of the best small cars of its era, a real piece of design thinking. The fact that CAR magazine’s George Bishop, at the time one of the top motoring writers in Britain, purchased a Visa for his personal use despite having access to any car he desired, spoke volumes of the Visa’s design brilliance. And Visa’s half-brother the Oltcit/Axel is an even more intriguing beast because it really was the last Citroën from the Bureau d’Etudes legacy.

Another significant figure of the greatest period in motoring writing, Ronald ‘Steady’ Barker, still cherishes his 2CV. The superb writer the late Phil Llewellin also preferred Citroëns, and in Andrew Brodie’s exquisite and essential book, An Omelette and Three Glasses of Wine – en Route with Citroëns, Llewellin and photographer Martyn Goddard (with Brodie) recounted the affair of Citroënism. The writings of L. J. K. Setright and, more recently, Stephen Bayley, also populate Citroënism. Setright always said you could judge a car by its steering: he was correct, and the art of steering quality is a key Citroën parameter. At the revered Octane magazine, editor David Lillywhite, who can get his hands on any supercar he wants, runs an SM.

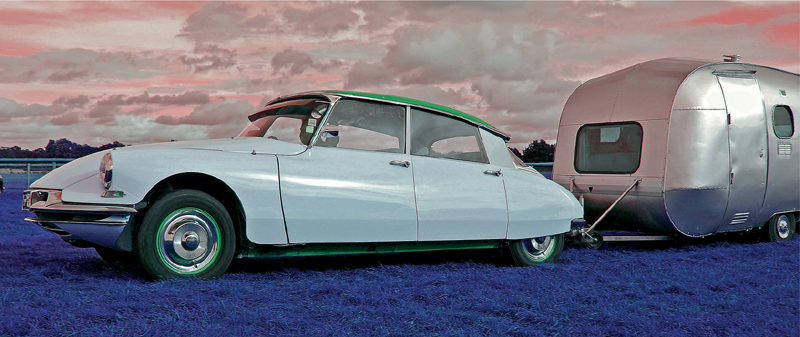

The Martians have landed. A British DS ‘moment’ made different.

My next affair with Citroën was with the CX – an intergalactic star cruiser of a car. Rashly I bought a pale metallic lilac blue one, a ‘Pallas’, which was a Citroën trim level stemming from the DS Pallas within DS or ‘Déesse’, meaning Goddess, to the derivation to Athene and Pallas of Greek legend. Later CXs were of ‘Athena’ in trim nomenclature. With vivid blue interior trim, ellipsoid furnishings, and chromed, Art Deco-style wheel trims, the CX Pallas was a styling sensation; it rusted, of course, yet when it worked it was motoring like none other. You had to re-learn how to drive in order to extract the best from its vari-power steering and suspension set-up. Once mastered, this new driving technique (inherited from the DS and the SM) created in the conductor a perhaps delusional sense of grandeur. And yet such sweeping, smooth progress in a big Citroën was majestic: had not the CX’s antecedent the SM, been coined ‘Se Majeste’?

Driving the SM was incredible, but the CX was also a sensation. You had to slide yourself into the CX, as you slide into a sports car – yet there was plenty of room. No wonder French Presidents rode in them. The delusion was delightful – but although that ‘CX’ attitude was of course irrational, at least it was different, a sense of a very special occasion. Could that be achieved in its contemporaries?

The 2CV, DS and SM are revered in such places as Indonesia, Laos, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Zimbabwe, Uruguay, and other unexpected places where many examples of these cars lie awaiting their fate under tropical skies. There is even a website run by Pierre Jammes, dedicated to the DS in Asia (wwwDSinAsia.com).

There are other good French cars, but the Citroën, ancient or modern, has something special, that spirit of a car, that sense of occasion that marks a true automotive experience. Thus Citroëns could be exotic, grandes routières of aero-weapons with style, or they could be curious oddball little cars designed for the rural peasant: whichever, they were often very bizarre by the standards of perceived normality.

However, experiences of the previous Citroën capacity for rust and electrical temper tantrums will be very familiar to older Citroën enthusiasts. Yet underneath there was the design ingenuity that kept us hooked. More recently my ZX diesel was totally fault and rust free – yet as this is written my BX leaves a trail of green LHM ‘life-blood’ fluid (the blood that courses through its pipework) on the driveway, and it has also cooked its wiring with a lovely little fire. One day I shall write a book entitled The Last Citroën on the Road to Rack and Rouen, but in the meantime, I still adore my Citroëns and now covet, with some abandon, an M35 rotary Citroën to go with an XM V6.

To Citroënistes (never people to assume anything) there is nothing unusual, nor abnormal about having a relationship with an inanimate metal object. Ask a French farmer or his wife about their white Citroën van or the XM hidden in the barn, question an Alfa Romeo owner, or VW camper-van enthusiast, or ask a sailor or a pilot, for they will know what the elusive yet elemental allure of a hull is about.Indeed, we must surely consider if a sucking, wheezing, whirring (and sometimes hydraulic) Citroën is inanimate? For a Citroën is, above all, a sometimes recalcitrant, stylish, extraordinarily engineered, living, French mechanical device bearing the badge of the chevron.

Paris: Citroën Revolte concept car makes its stunning mark as another pointer to Citroën’s design resurgence.

We should not confabulate the failings of Citroën’s past problems with build quality to any failing in design. The men of the Citroën studio – the Bureau d’Etudes designed cars – did not make them. The responsibility for poor quality and poor reliability was not theirs, so it is utterly incorrect to say that the act of advanced designs caused problems. It was the standards of the era, the manufacturing process and the weaknesses in execution that created the problems from which Citroën’s cars sometimes used to suffer: one could apply the same reasoning to many of the American car marques, or FIAT, or worse British Leyland and what it did to Jaguar and Rover.

Despite the intelligence of the SM and the brilliance of the GS, followed by the architectural CX, Citroën’s costs were huge. Teething problems were overcome, of course, and the cars’ essential correctness shone through (just as with the earlier Traction Avant), but the issues of development costs and build quality failings did, in the end, take Citroën to the edge of the financial precipice in the 1970s. Despite all this, the band of followers across the social spectrum, across the class divides, remained: there was an emotional bond between Citroën owners and their cars.

With body design by Kevin Nougarede,Wild Rubis was Citroën’s 2013 iteration of a 4x4 crossover-type concept.Wild Rubis is set to form the basis of the new DS7 model and may be seen in Citroën’s ‘DS-World’ showroom in Shanghai before going on sale in Europe.

Owning a Citroën still makes a statement. No wonder Jean-Jacques Burnell, the lead guitarist of The Stranglers drove a black CX Gti – and what of Russian President Leonid Brezhnev, who ordered a bright green-hued SM – champagne Citroënism at its height, it seems. The James Bond 007 music composer John Barry drove an SM, and so should have James Bond himself, but the closest he got was Roger Moore in a 1981 2CV.

DOUGLAS BADER AND A DYANE 6!

A surprising Citroëniste was Sir Douglas Bader, the aviator and World War II fighter pilot who so tragically lost both legs. One might have expected him to drive a Rover V8, or something with the status to match his powerful personality – yet Bader, at least in his later years, owned more than one Citroën Dyane. He could get from his West Berkshire home to London’s West End in just over forty-five minutes going ‘flat out’ (as he described it to this author) up the M4 motorway in the Dyane, with his pipe bellowing smoke and the police eventually giving up the chase in Hammersmith. What a contrast the likes of Bader, the belligerent RAF fighter pilot of 1930s construction, is to the C6 owner, DS3 fan, thespian and satirist Alexei Sayle. Therein lies part of the paradox of Citroënism amidst those of polar opposites, yet who make the same Citroën choice.

There are also the celebrity Citroën owners and enthusiasts (or the infamous), a roll-call that includes Idi Amin, John Barry, Stephen Bayley, Raymond Blanc, Steve Berry, Leonid Brezhnev, Jean Jacques Burnell, Lee J. Cobb, Monty Don, the Shah of Iran, Peter Cook, Johan Cruyff, Sebastian Faulks, Graham Greene, Lorne Greene, Alec Guinness, Mike Hailwood, Erich Honecker, Saddam Hussein, the last King of Laos, Jay Leno, Robert Lutz, Lee Majors, Jonathan Meades, Manuel Norriega, Burt Reynolds, King Haile Selassie, Will Self, Charlie Watts, Orson Welles. McLaren Formula One team boss Martin Whit-marsh owns a Mehari.

In royal circles Prince Rainer and King Harald of Norway both owned personal CXs: as a young princess, the later HRH Queen Elizabeth II had a Citroën pedal car, as did her sister the Princess Margaret, both courtesy of a royal visit to Paris in the 1930s.

CITROËNS AT THE PALAIS

France’s presidents mostly preferred Citroëns: Presidents Coty, De Gaulle, Pompidou and Chirac preferred Tractions, DSs and CXs, and an elongated SM and an XM also graced the presidential stables.

Back in the 1950s President Coty ordered a special long-wheelbase Traction Avant 15 Six H, a hydro-pneumatic Traction limousine built in 1955. President De Gaulle loved his DS, and his car saved his life with its abilities. Some presidents seemed to like the elegant Peugeot 604, but there were still Citroëns at the Palace. Jacques Chirac drove a CX Prestige Turbo for ten years before he got to the Palais de l’Elysée as president, while President Sarkozy left office in a C6, and President Hollande arrived in a C5 and took to the streets in a new DS5 – continuing the tradition irrespective of politics. Perhaps the next president of la crise economique will turn up in a 2CV!

A large number of British MPs also purchased CXs, and psychiatrists, too, often seem fond of them. Pilots loved the CX and the SM, and Lufthansa’s former senior Boeing 747 captain, Jürgen Renner, is a well known SM owner and ex-head of the German SM Club.

The Henri Chapron SM ‘Opera’ four-door saloon was launched in late 1972. Eight were built. This one is at Gloucester Cathedral during the 2013 European SM Club tour. Carrossiere Chausson also built a one-off SM saloon prototype; although stillborn, it influenced the later Maserati Quattroporte.

In truth, it cannot be denied that there was a time when Citroën slumped in the doldrums of product-minded, bean-counter control – but that was no more than a temporary moment. The smartly styled but tamely engineered Xsara felt more like a Ford, while the Saxo was Peugeot marketing and badge-engineering gone mad – but they sold and earned money for Citroën at a crucial period. It should not be forgotten that the so-called ‘normal’ BX was the car that saved Citroën in fiscal terms, a fact often ignored by the BX’s critics.

AT THE SIGN OF THE CHEVRON – DARING BY DELIBERATE DESIGN

Citroën design past and present is a forensic research psychology like no other, and I have tried to follow such thinking in this text. I have given some of the more modern Peugeot-derived cars less space than other Citroëns. That is my prerogative and my choice, because the real design interest lies in the older Citroëns and the recent designs, and less in certain 1990s Peugeot seeded devices. But as you will see, Citroën is back from the doldrums and is once again a shining diamond in the automotive design landscape.

Re-inventing tradition amid innovation is the true secret of Citroën past and present. The point is that it illustrates that the French are still better at intellectualizing things than everyone else. What other race would have put so much effort into something so mundane as a car? This intellectual ability, born of the grand colleges of France, is how and why the art movements, architecture, even French garden design, all came about from an ability to see things differently and innovate without prejudice; such behaviours are also the core of Citroënism, proof then of a distinct design thinking, a philosophy that happened to build cars.

It may be said by some observers that this book is as complicated as the cars it describes and the men it follows. That would be good, for it has to be so to do them justice, because they were different, and sometimes very complicated. Even the French have on occasion raised their eyes and sighed at the bizarre nature of certain Citroën design details.

Crediting the figures in the Citroën story is important, and I have tried to name the main players and the less well known supporting cast; any errors or omissions in the names of Citroën employees are unintended, and simply reflect just how hard it is to research events that took place decades ago. Clearly the entire cast of the factory or the service or dealer departments cannot all be named, but alongside the men of the Bureau d’Etudes we should not forget the welders, trimmers, testers, mechanics, service agents, dealers, mechanics and garagistes who were also members of the great family of Citroën across France, Europe and the world.

This is a book for the Citroën fanatic: it has been written for those who seek discussion of cars and their design. As a book in the ‘Complete Story’ series I am a hostage to such a claim, but herein subject to the limitations of space and personal choice is one Citroëniste’s version of a wonderful story. Not all will agree with the content or this author’s views and for those that do not, well, they have the opportunity to research and write their own Citroën books.

Here, in a new text unlike any other about Citroën, it is time to embark, ease into the rich brown leather and raise up the suspension, slide a chromed gear selector into its machined-alloy gate and begin your traverse across the seas of normality to arrive in the land of Citroën and its thinking.

Lance Cole

Redon, Bretagne Sud, France

Tobacco brown leather, polished alloy and ellipsoid mouldings can only mean one thing: SM supercar interior and the atmosphere of Citroën.