22 • COLLUSION

Lou stood up and moved to the whiteboard.

“A few weeks after Cory returned from youth detention, he asked me to use the car. I didn’t think my son deserved any privileges, and I didn’t trust him at all. But I could feel my wife’s pleading eyes, so I made a condition I was sure he’d refuse.

“‘You can take the car, but I want you home by ten o’clock.’ He was an eighteen-year-old boy, and it was a Friday or Saturday night. I was ready for his protests, but Cory surprised me by saying, ‘Okay. Thanks, Dad!’ The screen door slammed behind him.

“My wife wanted to watch a movie together, but my team was playing, so she read a book instead. I couldn’t keep my mind on the game. I was certain Cory would ignore the curfew, and I kept watching the clock. And in my mind I was sharpening my lecture for when he came home late.

“As the evening continued, I found myself more and more frustrated. Frustrated at Cory’s choices and what all of it meant for our family. Frustrated he couldn’t see that I only wanted the best for him. Frustrated that he wouldn’t even keep this one small commitment.

“By 9:58 my anger had burned down to a sort of weary resignation. And then, I heard tires squeal in the driveway. Cory burst in with a huge smile, threw me the keys and yelled, ‘Made it, Dad!’”

Lou shook his head. “That could have been a beautiful moment—a chance to recognize and praise Cory’s effort, to tell him how glad I was that he was home on time. It was an opportunity to strengthen our relationship. But instead I felt a keen pang of disappointment. And you know what I said?

“‘Sure cut it close, didn’t you?’”

Lou paused. “What must it have been like for my son? To come home from detention, facing the stigma and shame of public mistakes, only to be met by a father who could barely stand to look at him? It’s no wonder he went searching for other places to feel accepted.

“And, as you can imagine, my response didn’t encourage Cory to make curfew in the future. Why would he try if he was treated poorly no matter what? That type of interaction had become characteristic of our relationship. We were in collusion.”

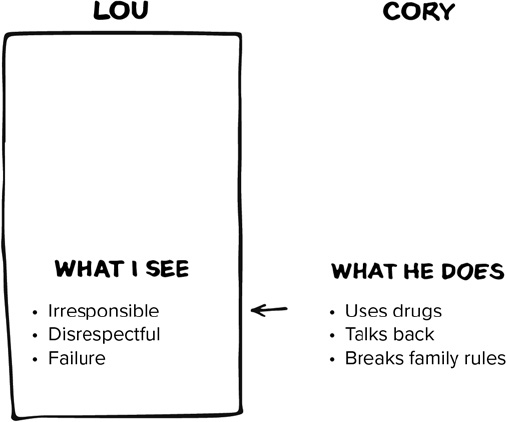

Lou drew a box with four quadrants on the board. He wrote “Lou” over the left side and “Cory” over the right.

“Why do you think I had a hard time seeing my son as a person? What was Cory doing that was so frustrating to me?”

“Well, doing drugs, for starters,” Tom said.

“Talking back, breaking family rules, being disrespectful,” Ana said.

“And getting arrested,” Theo said.

“Okay,” Lou said, writing these answers in the bottom right quadrant. “And how do you think I saw Cory when he did those things?”

“Well, if you were curious, you might have wondered whether he was acting out for attention or something,” Ana said.

“Right!” Lou said. “I could have seen that. But I didn’t because I didn’t really see Cory. I was inward toward him.”

“So maybe you saw him as irresponsible,” Ana suggested.

“Yes. What would you say, Tom?” Lou asked, writing Ana’s answer in the bottom left-hand quadrant.

“I’d see a disrespectful punk,” Tom said, thinking of his own teenager.

“It’s not easy to admit,” Lou said, “but I saw my son as a failure.” The words were stark on the board: irresponsible, disrespectful, failure.

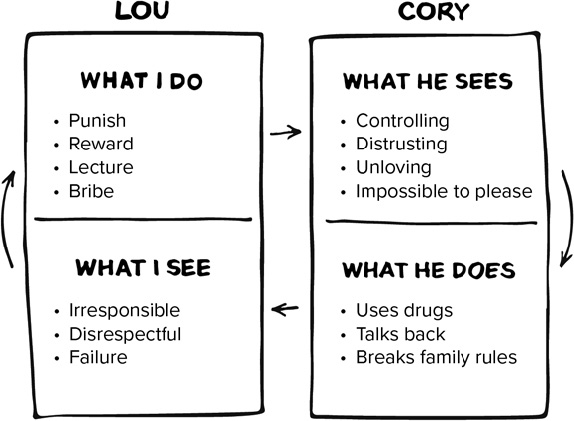

“And how was I acting toward Cory?” Lou asked, moving to the next quadrant on the board.

Figure 7: How collusion begins

“You said you tried all the punishments and rewards you could think of,” Ana said.

“Lectures, bribes, laying down the law,” Tom added.

Lou finished writing “punish,” “reward,” “lecture,” and “bribe” in the top left quadrant and turned to the group.

“Now,” Lou said, “I’m not crazy about punishing, lecturing, or the rest, but I don’t have much of a choice, do I? If Cory wasn’t doing the things he was doing, I wouldn’t have had to do the things I was doing! I was trying everything, but I wouldn’t have had to try anything if I just had a son who was responsible to begin with.”

“Couldn’t Cory be asking the same thing, though, just reversed?” Ana asked. “Like, ‘I wouldn’t have to talk back if my dad would listen to me’ or something like that?”

“I think you’re right,” Lou said, smiling. “Of course, no parent is ultimately responsible for what their child chooses. But even so, things might have gone very differently if my son had felt seen and heard by me. I couldn’t see my contributions, though. I thought I was doing all these things because of what Cory was doing. But why was I really doing them? What’s the link between Cory’s actions and my own behaviors?”

Tom’s eyes were fixed on the diagram. “The way you saw Cory.”

“That’s right,” Lou said. “That’s the key. I would have said that I was doing what I was doing because of the way my son was behaving. But the truth is, I was doing what I was doing because of how I chose to see my son. And, in return, how do you think Cory saw me, given how I was acting?”

“As controlling and distrusting,” Tom said.

“And with how you changed tactics,” Ana added, “he might have seen you as a dictator some days, then a pushover on others. Or at least as inconsistent.”

“Anything else?’ Lou asked.

“Unloving,” Tom said quietly. “Impossible to please.”

Lou added these to the fourth quadrant on the board, completing the diagram.

Figure 8: Collusion

“And when Cory interprets my actions as dictatorial and unloving, his disrespectful and rebellious responses make sense, don’t they?”

“Which then gives you more justification to tighten your grip,” Tom said. “That’s the cycle you were talking about.”

“Exactly right,” Lou said. “I was provoking Cory to behave in the very ways I said I hated. I was disappointed when he came home on time the night he took the car because, as strange it sounds, I actually needed him to be late. I wanted the justification that I could only have if he continued to be the problem I thought he was. You know, if you would have asked me just moments before he arrived home what I wanted most, I would have told you that I wanted my son to come home safe and on time. But it turns out that what I wanted most was to be justified. And him coming home on time got in the way of that. Anytime we blame someone else, we need them to be blameworthy.

“This is what happens in collusion. And Cory’s frustrating behavior was understandable given the inward way I viewed him and the ways I acted toward him. We were giving each other excuses to continue a cycle that only hurt us both.”

Theo added, “Cory and Lou provided each other nearly perfect justification, almost as if they collaborated to do so. That’s why we call it collusion.”

“Right,” Lou said. “It’s as if we crave justification so desperately that we say to each other, ‘I’ll mistreat you so that your bad behavior toward me is justified, if you’ll mistreat me so that my bad behavior toward you is justified.’

“Of course, making that sort of agreement would be absurd. But when people are in collusion, they can’t see the twisted way they are working together to provoke ongoing mutual mistreatment.”

“It’s not that we enjoy problems,” Theo said, “and it’s also not to say that we are responsible for the poor behavior of others. But when we’re self-deceived, justification becomes our highest priority. And often, whatever we are complaining about is the very thing that justifies us, so we turn a blind eye to our own contributions and fixate soley on the mistreatment we receive from others, reinforcing a belief that in many circumstances is a lie: the belief that the other person we’re in conflict with is entirely worthy of blame and we are completely in the right.”

“But what was Lou supposed to do then?” Tom asked, exasperated. “Sit back and let his son do drugs? Stand by while he ruined his life?”

“Of course not,” Lou said. “But my problem wasn’t in trying to discipline or correct Cory. In fact, I felt an obligation to intervene and help my son. But,” Lou said, holding up two fingers, “there are two ways to do almost any behavior—with an inward mindset or with an outward mindset.

“My problem was that I was inward toward Cory. I wasn’t seeing his full humanity, and my self-centered motivations tainted my other actions. How likely is anyone to accept correction from someone who sees them as a failure or an embarrassment?”

“When we’re inward,” Theo said, “it is almost impossible to invite positive change. Each action and choice we make is undermined by the distorted and self-serving ways we’re seeing ourselves and others.”

“Right,” Lou said. “My inwardness toward Cory was mostly manifest as forceful attempts to discipline.”

“And that usually backfires,” Tom said.

“Right,” Theo said. “But it isn’t just the behavior, it’s the underlying mindset too. Lou could have adopted totally opposite tactics and still have been equally inward and equally ineffective.”

“Exactly right,” Lou said. “If I had been more permissive of Cory because I was afraid of confrontation or wanted to be seen as nice or cool, it would have been just as self-centered as my impatience and frustration. And when we’re not seeing others as people like we are, our influence won’t just be ineffective. It will be destructive.

“But I didn’t understand that—not until we took Cory to a treatment program in Arizona.”