24 • SEEING CLEARLY

After a short break, the four of them were settling back in when Tom turned to Lou. “So how did you turn things around? Kate obviously came back, and the company has thrived. I’d guess things got better with your son too. What did you do to fix things?”

“There’s a lot that doesn’t work to cure self-deception,” Lou noted. “In fact, most of our attempts to fix our problems don’t work. We can try to change others or grudgingly cope with them, we can communicate more or distance ourselves, we can practice new techniques and behaviors, and after all this, absolutely nothing changes for the better. The painful reality is that the majority of leadership interventions fail.”

“Good pep talk, Lou.” Theo grinned.

Lou smiled. “Well, let’s be honest. The reason most attempts fail is because they’re focused on the wrong thing: they’re focused on changing behaviors, not addressing mindsets. They’re focused on the symptoms, not on the problem itself.”

“Which makes sense,” Theo added, “because unproductive behavior is so often what signals that a problem exists in the first place. It’s tempting to think, ‘If we can just get them to meet deadlines or speak up or change whatever they are doing that’s causing an issue, then the problem will be solved.’”

“But the change doesn’t stick, or the problem shows up in a different way,” Lou added, “because the underlying issue wasn’t addressed.”

“Like with Semmelweis,” Ana said.

“Exactly right. The problem of self-deception is deeper than behavior,” Lou continued. “So the solution has to be too. If we want to cure inwardness, objectification, and blame, break free from collusion and escape the lies and self-images that exacerbate dysfunction, we need to first see clearly.

“Once I woke up and started really seeing the people around me, I knew exactly what to do,” Lou said. “And more importantly, I was able to do it in an outward way that actually made a difference because it wasn’t contrived or self-centered.”

“They say a proper diagnosis is half the cure,” Theo said. “But when it comes to collusion and self-deception, it’s almost as if the diagnosis is the cure. When we see others clearly, the most helpful steps to take become clear. In some cases, being outward will mean that we take a more gentle approach with others than we have in the past. But in other situations, being outward will mean just the opposite. Where we have indulged poor behaviors in others, seeing them as people will help us be more direct and straightforward. Often hard behaviors are more helpful—like setting boundaries and enforcing consequences. But, again, the ‘right’ behavior only works when it comes from the right mindset.”

“I had a long list of apologies to make,” Lou continued, “to Cory, to Kate, and to others. I asked for feedback regarding what it was like to work with me, and I listened longer and deeper than I had before. I adjusted my efforts to try and have a better impact. Those steps alone made a remarkable difference.”

“Lou’s experience is a great example,” Theo said. “It demonstrates how the cure to self-deception is simple to say and hard to live: turn outward. That means getting curious about the people around you and honoring the outward, helpful senses you have toward them. It means letting go of any belief that you are better than or worse than others. Because then, you don’t have to waste time feeling inadequate or blaming other people. You don’t misplace precious energy trying to present a facade that you are nice or successful or competent. When you’re outward, you can simply be invested in the work you’re doing with people who matter like you matter.”

“It’s that easy, huh?” Tom said.

Lou smiled. “It’s a helluva lot easier than the way I used to live. I was an expert at mining for justification, but it never satisfied. My life has been more rich and fulfilling—and my work immensely more productive—the more I see and respond to others.”

“Just to be clear,” Theo chimed in, “turning outward isn’t a onetime achievement. It’s a practice. Over and over again, Lou and Kate and I have to catch ourselves in self-deception and justification and come back to clarity. All of us have to notice and set aside the chronic self-images we carry around so that we can really be with people.”

“And there’s no better time to practice than the present!” It was clear to Tom and Ana that this “no time like the present” mantra was one of Lou’s favorites. “Are you two ready to tackle that collusion between your teams?”

“Let’s do it,” Tom said.

“Ana?” Lou said. “What do you say?”

Ana exhaled. “I’m sure we could use all the help we can get.”

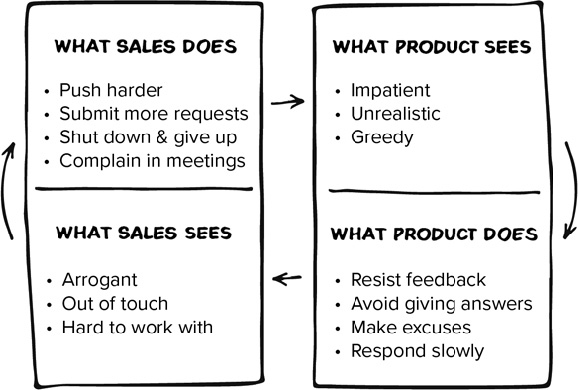

Theo stood up, drew a new four-quadrant box, and wrote “Sales” on the left and “Product” on the right.

“All right, this could be a little risky,” Theo said. “There will be opportunities to take offense and turn inward. Are you two sure you’re ready?”

Tom and Ana looked at each other.

“We’re good,” Ana said. Tom nodded.

“All right,” Lou said. “Let’s start with you, Tom. What is your team doing that is so frustrating to Sales?”

“Well,” Tom said, “it sounds like we aren’t as open to feedback as Sales would like, especially to what they’re learning from customers.”

“What else?”

“That we’re not straightforward. What did you say yesterday?” Tom asked, turning to Ana. “We just send back jargon to avoid giving real answers?”

“Yeah, it just feels like excuses that are intended to be confusing,” Ana said.

“Got it.” Tom paused. “I think that’s about it. Oh, and that we’re slow to respond to product requests.”

“Okay, great,” Lou said as Theo added the last statement to the bottom right-hand quadrant.

Theo smiled. “And given all that, Ana, how is your team seeing Product? What did you say yesterday?”

“Arrogant, out of touch with the customer, and hard to work with.”

Theo wrote this in the bottom quadrant on the Sales side of the diagram.

“And seeing Product this way, Ana,” Theo asked, “what does your team do?”

“Well, we tend to push harder by sending more emails and submitting formal requests. Either that or we shut down. Depends on the team member, I guess.

“And I’m embarrassed to admit this, but we’ve spent too much time complaining about Product in our Sales meetings. Plenty of griping without talking to the product team directly.”

“Not that we’ve made communication easy though,” Tom said.

“Well, yeah, but I know the passive-aggressive emails aren’t helpful—especially when we copy other VPs to add pressure and make sure they can see how hard we’re trying.”

“Ha! The dirty email power play.” Tom laughed. “We hate that!”

The two of them were staring at the collusion diagram that was staring back at them.

Ana laughed. “Seeing this so starkly, I’m not surprised that you would see us as impatient, unrealistic, and…what was it you said yesterday?”

“Greedy,” Tom said, grinning.

“Right, greedy!” Ana said. “And everything we’ve been doing just reinforces all of that.”

As Ana spoke, Theo finished filling out the diagram.

Figure 9: Collusion between teams

“I’m sorry I haven’t come to talk to you about this, Tom,” Ana continued. “I should have modeled more straightforward communication for my team.”

“Well, we’d like to think we know exactly what we’re doing in Product, but I think we actually are too far removed from the customer and your team to be truly effective,” Tom admitted. “I haven’t helped my people be as curious as we need to be.”

“Your team has made some impressive strides,” Ana said. “And I think we could really revolutionize things for our clients if we worked better together.”

“Maybe we can ask for help to comb through and combine some of the product change requests to reduce redundancy,” Tom said. “That would help us respond more quickly.”

Theo had taken his seat while they were talking to each other, and only now did Ana and Tom notice. What Tom and Ana had seen—the diagnosis—was already doing its work.

“Look at the board,” Theo said, smiling. “Finally recognizing how the inward ways you have been seeing each other drives the problematic behavior that you thought was justified—that’s enough to discover a better way.”

Lou clapped his hands. “The future looks bright, Theo. Don’t you think?”