ONE NIGHT about sixty years ago, my grandmother and grandfather were awakened by the steady howling of a dog. My grandmother touched my grandfather’s shoulder and said to him in a frightened voice, “Oh, Angus, listen, that is a sign of death.” Jumping out of bed, Angus said, “You’re damned right it is—if that dog is still there when I get down the stairs and out the door.” If events fade into legend and legend into superstition, superstition eventually fades away altogether, and it is impossible to say how that one made its way to my grandmother in Ohio; but if it came from Colonsay one certainty now is that it has long since vanished from the island. Legend hangs above the Hebrides more thickly than clouds, but the

people pay even less attention to these things—to haunted dogs, seal women, seers, mermaids, elves, fairies, glaistigs, gigelorums—than they do to the rain. Donald Gibbie believes in nothing supernatural, and he says he knows few people who do. Donald Gibbie spends his time worrying about, among other things, the Common Market and “what effect Great Britain’s entry into it might have on subsidies as we know them.” It is not the islanders who preserve the early magic of the island. It is the women who stay at the inn—the ones with the knitted caps and tweed skirts and walking sticks, some of whom have brought their own shepherd’s crooks with them from Edinburgh. At home in Midlothian, they belong to organizations like the Highland Hall Association and the Edinburgh Gaelic Circle, and they go to regular meetings where, in effect, they burn tartan candles. In their heads hang splendid tapestries of Hebridean lore and legend, and when they come to the island, for their brief visits of a week or ten days, they become solitary silhouettes in the heather on the hilltops, drinking in the air of ages past and imagining themselves to be in the company of forms unseen. They themselves are inconspicuous—Donald Gibbie says he sees them only when they get off the Lochiel and again when they get back on—and they are sometimes unexpected. Two or three days ago, a fine-tweed lady with powdered hair and a varnished crook jumped out from behind a whin bush, tugged my sleeve, and told me not to kiss a fairy or I might never see the human world again. These women know the history of the island. On the moorlands of Balaromin Mor, one of them asked my name, and when I told her she said, “I thought as you approached

that I was seeing a ghost, and now I know that a ghost is what I see. What is your Christian name?”

“John.”

“Have you another name?”

“Yes, I do.”

“What is that?”

“Angus.”

“The Cross of Christ be upon us.”

This woman, who introduced herself as a Jardine of Applegirth, told me that she believed she had second sight, and suspected that I had it, too. Second sight is one of the immemorial talents of the Highlands. People of Colonsay are said to have possessed it, but none was ever particularly noted for it. The greatest man of all time in this field was Kenneth Mackenzie, the Brahan Seer, beside whom Nostradamus, a near contemporary, should have paled into French insignificance. Mackenzie was a farm worker in what is now Ross and Cromarty. In a later day, he might have been a crofter. Word of his power spread when he began predicting with accuracy not only certain deaths and other local events but also the birth of a child with two navels and another with four thumbs. Soon, he began to travel the Highlands telling the future. He said that ships would one day sail behind Tomnahurich Hill, in Inverness, predicting, a hundred and fifty years before its construction, the Caledonian Canal. Walking on Culloden Moor, a hundred years before the clans were destroyed there, he said, “This bleak moor shall, before many generations have passed away, be stained with the best blood of the Highlands. Glad am I that I will not see that day, for it will be a fearful period. Heads will be cut

off by the score, and no mercy will be shown or quarter given on either side.” He also said, on another occasion, “The clans will flee their native country before an army of sheep.” A third prophecy in this progression has not yet been fulfilled. The Brahan Seer said that eventually even the sheep would be gone and “the whole country will be so utterly desolated and depopulated that the crow of a cock shall not be heard north of Druim-Uachdair … . The deer and other wild animals in the huge wilderness shall be exterminated by horrid black rains.” Mackenzie had his lighter side. He said, “The time will come when whisky or dram shops will be so plentiful that one will be met with almost at the head of every plow furrow.” His fame became universal in the Highlands, and he a figure of importance everywhere. Donald Gibbie, with a smirk of disavowal, has given me a biography of the Seer that once belonged to his father. The Seer was apparently not only shrewd but also sarcastic, flippant, caustic, and funny, and these attributes brought about his death, after the wife of the Mackenzie chief summoned him to Brahan Castle and asked him if her husband was safe. For many months, the Mackenzie had been in Paris. “Safe? I would say so,” said the Seer.

“What is he doing?”

“He is happy and merry and kissing the hand of a woman with his arm around her waist.”

This infuriated the chief’s wife, who decided that the Seer had made his last guess, and Mackenzie did not soften the case against him when he looked over the highborn children playing in the castle yard and said that most of them appeared to have been sired by gillies and lackeys.

Thus it was that the Brahan Seer was dropped into a barrel of boiling tar. Knives had been driven into the sides of the barrel. He said a word or two before he went. He said, “I see into the far future, and I read the doom of the race of my oppressor, whose long-descended line will, before many generations have passed, end in extinction and in sorrow. I see a chief, the last of his house, both deaf and dumb. He will be the father of four fair sons, all of whom he will follow to the tomb. He will live careworn and die mourning, knowing that the honours of his line are to be extinguished forever, and that no future chief of the Mackenzie shall rule at Brahan or in Kintail. As a sign by which it may be known that these things are coming to pass, there shall be four great lairds in the days of the last deaf-and-dumb Mackenzie chief—Gairloch, Chisholm, Grant, and Raasay—of whom one shall be bucktoothed, another harelipped, another half-witted, and the fourth a stammerer. When the last chief looks around him and sees them, he may know that his sons are doomed to death, that his broad lands shall pass away to the stranger, and that his race shall come to an end.” The Brahan Seer then went into the tar. Many generations later, a deaf-and-dumb Mackenzie chief came along. He had four sons. Among his contemporaries were the Chisholm of Chisholm, who was harelipped; the laird of Gairloch, who was bucktoothed ; a half-witted Grant, who was a laird as well; and the stammering laird of Raasay. The four Mackenzie sons died before their father, and with him the line was extinguished forever.

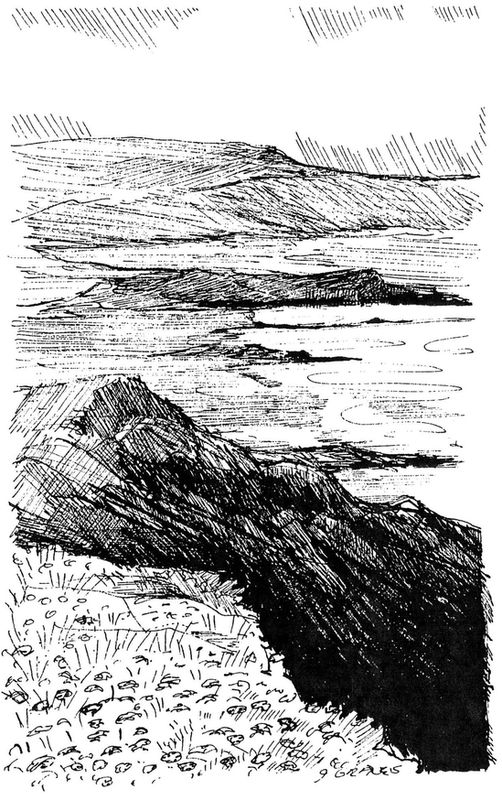

Along the shores of Colonsay, and particularly of Oronsay, conical mounds rise like miniature green volcanoes.

These are sithein, said to have been once inhabited by a race of sith (little people), who wore conical green caps, green coats, and green kilts. These little people bracketed the world with good and evil, extending benevolence to ordinary humans who treated them well and devising unhappiness for people who treated them badly. Things left beside their hillocks for mending or repairing would be taken care of in the night. They knew cures for diseases. They played small bagpipes, and they ate silverweed and heather. Their women could assume the shape of deer. They made love to human beings, and, perhaps not surprisingly, they were more faithful to their lovers than their lovers were to them. They could not go below the high-water mark. They travelled in the eddy winds.

“Sith” (pronounced “she”) also meant “the people of peace,” “the still folk,” “the silently moving people.” There was once no question in anyone’s mind that they existed, and milk was poured into the ground to feed them. The membrane was very thin, in the islands, between the supernatural world and the physical world, and sometimes there was no discernible separation at all. History proliferated into fantasy, and pure fantasy became history. Science may erase these things, but in a sense they were true once, and they are not entirely forgotten. In the sixth century, when St. Columba lived briefly on Colonsay, he was given some land in Garvard on which to build a church, so the story goes, and the result was Teampull a’ Ghlinne (the Temple of the Glen), whose ruins—thick walls, arched windows—are still there, close to the boundary of Balaromin Mor. The little people frequently used to dance by the Temple of the Glen in the night, always

singing a monotonous song of theirs, the complete lyrics of which were “Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Saturday.” A hunchback from Balnahard came and joined the party one night, shouting out the lyrics with joy and carefully omitting mention of the word “Friday,” because he knew it was forbidden among the sith. The little people sent him back to Balnahard standing straight and humpless. Another hunchback, who lived in Kiloran, heard about this and showed up at the next dance at the temple. “Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday,” sang the little people, and the Kiloran hunchback belted out a thunderstriking “Friday.” He went home with two humps—his own and the hump of the hunchback of Balnahard. Among the sith, Friday was never mentioned by name. It was called the Day of Yonder Town.

Scottish surnames and the Highland clans began to evolve in the second half of the eleventh century. Many of the names had religious sources. “MacPherson” meant “son of the parson,” “MacTaggart” meant “son of the priest,” “MacVicar” meant “son of the vicar,” “Macnab” meant “son of the abbott,” “MacLean” meant “son of the servant of St. John.” In its earliest Gaelic form, my own name—McPhee, that of Colonsay’s original clan—was Mac Dubh Sith. The word “dubh” means “black,” and referred, in part, to the characteristically swarthy skin of these early people of the island. After they developed their tartan—of green, yellow, white, and blazing red—they added a variant sett that was simply black and white. The braid of their beginnings is not particularly obscure. A few of the green conical mounds have been opened, and

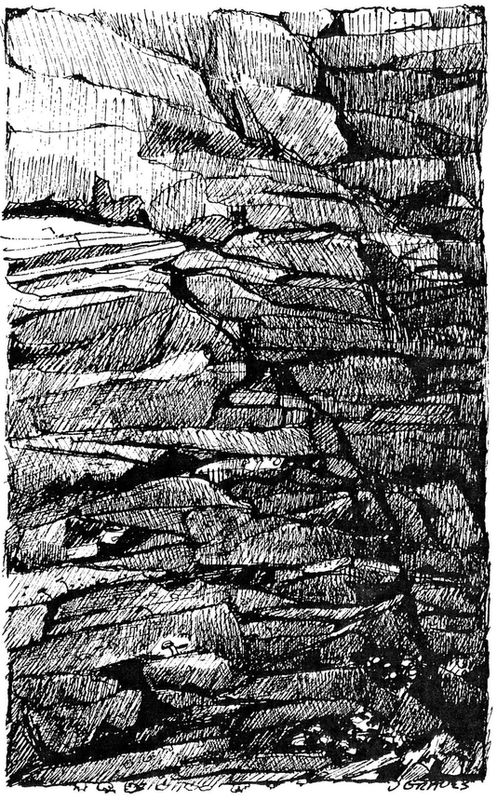

within them were bone implements, stone hammers, barbed harpoons, thousands of shells, and the bones of great auks, red deer, seals, dogfish, finback whales, wild swans, sheep, rats, rabbits, boars, otters, martens, guillemots, razorbills. These were the kitchen middens of people in the Stone Age and, thereafter, of the Picts. Middens at least as extensive fill the fingery recesses of Colonsay’s innumerable caves (the Piper’s Cave, the Lady Cave, the Endless Cave, the Crystal Spring Cavern), where, mixed in a preserving muck, are the leavings of meals eaten by centuries of successive or concomitant tenants—by Dalriadic Scots, by Norse and Danish Vikings, and by the Celts, the Caledonian Gaels, who were known as people who endlessly asked questions, who kept larders of their dead enemies, and who described their world as Earraghaidheal (the Border of the Gael), and pronounced it, more or less, Argyll. With Ian Summers, an unredundant employee of the laird, I went to the Lady Cave a few days ago, at the north edge of Kiloran Bay, and set up a paraffin lantern in the absolute blackness of a tunnel offshoot that reaches back under A’ Bheinn Bheag (the Little Peak), in Balnahard. The midden muck there was seemingly bottomless and was full of implements of bone and stone, and, of course, the inevitable multitude of shells. Prone in the muck, we worked systematically, following a small grid and sorting what we found. When you have in your hand the stone tine with which a man in an animal’s skin ate a shellfish, the ticking of time present is incredibly accelerated. Six hours went by and the lantern was beginning to flicker after what had seemed like thirty minutes. My finger, going down in the muck just before we quit for the day, happened to go right through the center of the circle of a bronze penannular brooch, and when I raised my hand the brooch came with it. I took it to the laird, since everything belongs to him, and he told me to keep it. He has at least a dozen such brooches in the showcase in Colonsay House with the last iron spike of the Canadian Pacific. Ancient middens are not the only middens on Colonsay. Without any apparent aesthetic conscience, the people of our own era pile their used tins and plastic bottles in pyramidal dumps near the edge of the sea, and these in time may become embedded in muck and sheathed in green.

The Vikings lived in the Hebrides for four hundred years and were there when the clans developed. The island clans were, in fact, Celto-Norse, and on Colonsay the Vikings were more numerous, proportionately, than they were on the other islands. They were, in one era, followers of Magnus Bareleg, so called because when he went home he introduced the kilt to Norway, where kilts became a fad that lasted for many years. “Havbredey,” a Norse word, meant “isle on the edge of the sea.” “Scalasaig” and “Uragaig” are words of Norse derivation, and “Sgeir nan Locharnach,” on the Ardskenish Peninsula, means “the Norsemen’s Skerry.” When one of the green mounds of Oronsay was opened in 1891, a Norse ship was found, and in it were the skeletons of a Viking and (nil nisi bonum) his wife. Viking boat burials have also been uncovered in Machrins and Kiloran Bay, but most of the green mounds are thought to have been assembled by Picts or other early peoples whose existence, transmogrified in story, underlies the legends of the sith. In

Popular Tales of the West Highlands (1890), the classical work on Hebridean legend, J. F. Campbell said of the history of the sith, “This class of stories is so widely spread, so matter-of-fact, hangs so well together, and is so implicitly believed that I am persuaded of the former existence of a race of men in these islands who were smaller in stature than the Celts, and who used stone arrows, lived in conical mounds, knew some mechanical arts, pilfered goods, and stole children.” Some of these small people of peace were not the most attractive beings in the world. They might have had one Cyclopean eye, or a large single nostril. The Woman of Peace, bean shith (the Banshee), had a huge single front tooth, preternaturally long breasts, and webbed feet. In one sitting, she could eat a cow. When a crop failed or an animal died, the still folk were said to have taken its essence, not its substance. They did steal mortal children.

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping

than you can understand.

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping

than you can understand.

Mrs. Henry Pitney Van Dusen, wife of the retired president of Union Theological Seminary in New York, grew up as a Bartholomew, in Edinburgh, where her husband took a part of his theological training. As a young couple with infant children, the Van Dusens spent parts of several summers on Colonsay, and when I was about to leave the United States for the island, Mrs. Van Dusen,

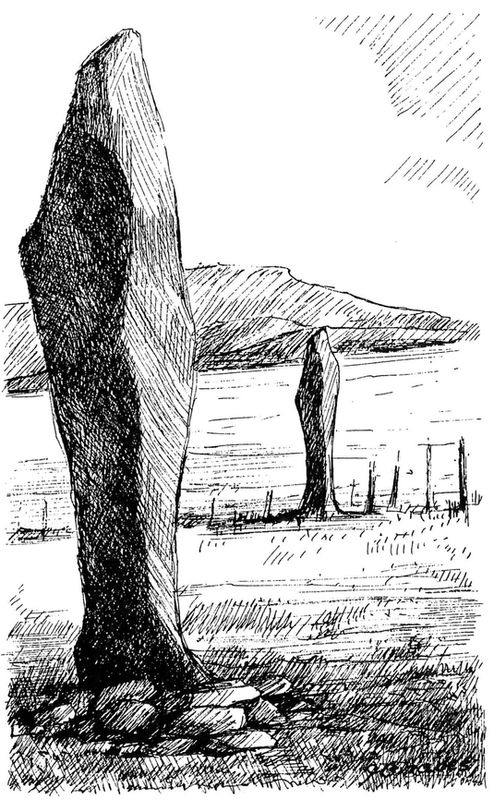

who is now a neighbor of mine in Princeton, said to me, “You must always put birch branches over a baby’s cradle or baby carriage to protect it from the fairies. I did this very carefully in Colonsay.” The legends of the still folk and of related beings and phenomena have not always persisted so impressively; nor, when they have, have they very often penetrated so close to the spiritual epicenters of the modern world. Nonetheless, they seem to have grown, not to have atrophied, across the centuries. The large seeds of a treelike West Indian plant called Entada scandens have drifted to the shores of Colonsay for thousands of years, and they have always been called fairy eggs. People once wore them around their necks, believing that this protected them from the evil moods of fairies. Below the foundation of a new house, a cat’s claws, a man’s nails, a cow’s hooves, and a bit of silver were traditionally buried, to keep the little people happy. Such practices and fears have pertained to all eras, ancient and modern. If a man, in more recent times, became frightened of the still folk while walking alone at night, he would draw a circle around himself and say, “The Cross of Christ be upon me.” A troubled man in an earlier time would go, perhaps, to the summit of Ben Earrnigil, in Garvard, or to the great stones of Kilchattan, to seek reassurance from his Druid. At the summit of Ben Earrnigil is a stone circle a hundred and eight feet in diameter north to south and ninety-eight feet in diameter east to west. Stone circles in Kilchattan and elsewhere on Colonsay—and, for that matter, wherever they exist in the world—characteristically have this slight elongation, thought by some to represent the pattern of the orbit of the earth around the

sun, which the Celts and their Druids worshipped. As Christians would build their cathedrals in the shape of crosses, the Celts built theirs in circles of the sun, and into the twentieth century in Argyll people used the expression “going to the stones” when they meant “going to church.” The Druids apparently recorded nothing. It is thought that they kept their law, philosophy, and theology in their heads, committing to memory during their period of training some sixty thousand rhymed verses, not a few of which were powerful antidotes to any threat that might rise from the still folk and the forces of the dark. The standing stones in Kilchattan, beyond the graveyard from Donald Gibbie’s croft, have an abstract beauty of form and balance that has only recently been appreciated in sculpture. There are two. They stand about fifty feet apart. They are about ten feet high. What makes them so graceful is that they are quite narrow at the point where they emerge from the ground and they expand upward in an inverted taper, so that their effect on the eye is a sense of weight and force poised in the air, beyond the world. Thought by some to be a part of an otherwise vanished circle, the standing stones of Kilchattan have also been described as possible remnants of a Druid astronomical observatory. Donald Gibbie told me that the crofter on whose croft they stand once tried to start a posthole by jamming a four-foot crowbar into the ground between the two stones, and the crowbar disappeared into the earth—into some kind of subterranean chamber—and has never been recovered. The stones, tall and slim, are visible from a long distance up the glen of Kilchattan. They are dark against the sky, and they stand in a field of grain. They are called Fingal’s Limpet Hammers.

A piper once entered a cave on the northern shore of Kilchattan playing “The Lament for Donald Ban MacCrimmon.” He was followed by his dog. The piper was never seen again, but the dog eventually reappeared five miles away, on the coast of Balaromin Mor, and the dog’s hair was scorched. So goes the legend of the Piper’s Cave. Colonsay had its outsize beings as well as its little people. They were known as the Fomorian Giants, and their mother, the Cailleach, was the spirit of winter. She had a single eye, just above her nose. She kept a young girl captive, and eventually the girl’s lover attacked the Cailleach, who avoided his assaults by turning herself into a gray headland, always moist, above the sea. This is Cailleach Uragaig, where Donald Gibbie stood on the pinnacle rock of the McNeill lairds. It was said for centuries that maighdean mhara (mermaids) sat among the skerries combing their hair at night. The ichthyic sheaths that covered their lower parts were removable. An islander could keep a mermaid as long as he kept her fishskin, but when she recovered it she would always put it on again and vanish into the sea. The largest creature anyone had ever heard of was the Great Beast of the Ocean, and to give an idea of its size people said that seven herring are a salmon’s fill, seven salmon are a seal’s fill, seven seals are a whale’s fill, and seven whales are the fill of the Great Beast of the Ocean. The smallest creature anyone had ever heard of was the gigelorum, which made its nest in the mite’s ear, and this is all that was known about it. If a

cuckoo cried from the roof of a house, a death would come to that house that year. If your nose itched, you knew that a letter would soon be delivered to you. If your mouth itched, a dram was coming. If your ears tingled, a friend had died and the news would come soon. If your elbow itched, you knew that you would soon sleep with a stranger. Turning a boat around, passing out drams, walking around a house you were about to enter—you went to the right. You did all such things in the direction that corresponded to the course of the sun. When a young woman combed her hair at night, she put every loose strand in the fire. If the hair did not burn, it meant she would one day drown.

If a girl did drown, she might become a seal. Then once a year she could, if she liked, step out of her phocine skin and walk the earth as a human being. The shores of the Hebrides have always been populated with seal maidens, sunning themselves on boulders above the waves, their sealskins draped nearby. Once, a mainland girl betrothed to a young man of Colonsay was drowned on the voyage she was making to the island to marry him. In his melancholy, he hunted the shores for years, and finally he found her. He stole her sealskin and hid it, and then he took her home with him. He married her. Seal maidens could live among mortals and could marry and have children, and frequently enough they did, but they always felt a powerful draw to the sea, which they sometimes found irresistible. This one bore the children of the man of Colonsay and had good years with him, but her longing for the ocean finally overcame her. She found the sealskin where her husband had hidden it, and she disappeared. This is

the germinal story of the original clan of Colonsay. From her children—so the legend goes—the clan proliferated.

From their earliest beginnings, in the eleventh century, to their full development, in the thirteenth century, to the Battle of Culloden, April 16, 1746, the clans lasted seven hundred years. In the nineteenth century, during the Pan-European wave of Highland nostalgia when Angus MacKay was piping for Queen Victoria and Felix Mendelssohn was writing the “Scotch Symphony” and his concert overture “The Hebrides,” the Scottish artist R. R. McIan completed a memorial set of watercolor portraits of Highland clan chiefs, and these portraits have ever since been regarded as the best of their kind. McIan’s chief of Colonsay appears on the shore of the island, the hills of Jura rising in the distance over the water behind him, and the look in his eyes, as he stares—full of attention —out to sea, suggests that whatever boredom his island life may cause him is frequently relieved. He appears to be relatively young still, but only moderately fit. Beneath his long shirt of chain mail there is an obvious paunch. He is dressed for feud. His left hand is on his hip. His right hand holds two spears. Hanging from a rent in the chain mail is a sword that must weigh twenty-five pounds. His boots are of untanned leather. He wears a conical helmet of the type the Vikings used, and it is decorated with an upthrusting eagle’s wing. His beard is full and has an auburn glint. When he was first acknowledged as chief, he stood on top of a cairn, holding in his hand a white rod that symbolized his responsibilities, and he swore that he would preserve the customs of the people, one of which was that without regard to one’s position in the clan it

was every clansman’s first duty to go to the aid of any other clansman in time of need. A bard then recited several hundred verses in his praise. He became chief because he was, at the time, considered the fittest member of his family, and thus did not necessarily succeed his father nor will he necessarily be succeeded by his own son. The tanist, heir apparent to the chief’s position, may be a brother, a cousin, a nephew, and the tanist’s power is considerable —he is the administrative trustee of the lands of the clan. When the chief replaces his chain mail, he will put on his plaid—a huge bolt of tartan cloth, two yards wide, about six yards long. He drapes it around himself in careful pleats—the archetypal kilt—and holds it in place with a leather belt and a brooch at the shoulder. When he travels, he sleeps in his plaid and nothing more, even in snow. The tartan cloth is dyed with vegetable extracts that yield colors so soft that the tartan all but blends into a background of heather. The women of the clan wear tartan shawls, and flowing tartan or plain-colored gowns that are secured with brooches. Over their hair, they wear linen that is fastened beneath their chins. The clansmen eat barley cakes and oatcakes for breakfast and barley cakes and oatcakes for lunch. The meats for dinner—mutton, venison, beef—are boiled in the stomach of the animal they came from. The preparation of meals is simpler during hunting or feuding expeditions. The flesh of killed animals is squeezed to reduce the blood content, and then eaten. The clansmen eat fish, too, and in token of the sense of equality that pervades the clan, everyone’s fishing line is by custom the same length. The chief has lighted his share of fires at the mouths of caves on other islands

in order to choke to death the hiding families of his enemies, and with his heavy sword he has performed decapitations, sometimes retaining as trophies the heads he has severed. In times of major purpose, he has fought beside the very people who might otherwise have been killing him or he them. With them all, as Scott would one day remember, he answered the summons to Bannockburn.

Lochbuie’s fierce and warlike lord

Their signal saw, and grasped his sword,

And verdant Islay called her host,

And the clans of Jura’s rugged coast

Lord Ronald’s call obey,

And Scarba’s isle, whose tortured shore

Still rings to Corrievrekan’s roar,

And lonely Colonsay.

Their signal saw, and grasped his sword,

And verdant Islay called her host,

And the clans of Jura’s rugged coast

Lord Ronald’s call obey,

And Scarba’s isle, whose tortured shore

Still rings to Corrievrekan’s roar,

And lonely Colonsay.

The stream was not entirely red. The clan’s name implied that its people were people of peace, and the chief made some effort to alleviate the irony. The parliaments of the isles were held on a small island in Loch Finlagan, on Islay, and at these councils—attended by the clan chiefs of the Hebrides and presided over by the Lord of the Isles—the chief from Colonsay kept a journal of what went on. He was the traditional secretary, recorder, scribe. After the clan was broken, all records kept by the chiefs of Colonsay were destroyed by the MacDonalds, so what was written is unknown, but one hopes that beyond the drone of deliberations certain details were not omitted—the passing of the goblet full of true cognac, imported by twenty-oared galley from France; the exertions of the

Orator, a bardlike functionary who composed his speeches by lying on his back with a huge rock on his stomach, the idea being that golden rhetoric would thereby more thoroughly be pressed out through his brain. The chief also was present, among the chiefs of the larger clans, at a colloquium held on the island of Iona, where he and the others wrote and signed the Statutes of Icolmekill. In this document, the men of the isles reluctantly acknowledged the course of history as it was developing and decreed that certain children of the clans should be sent to Lowland schools to learn English.

On a shoulder of the hill of the Candle Cairn, in Scalasaig, the chief of Colonsay built a fort called Dunevin. Its ruins are still there, beneath sod, and are most evident from a distance, for the top of the rise is square, with green ramparts. The islanders call it the Green Hill. Heather apparently won’t grow where the earth has been disturbed by the battlements of the past. The view from Dunevin, once protective, is now merely spectacular, with the other hills and ranges of Colonsay paying out in all directions above the island’s glens, surrounded by the framing sea. In the fields below Dunevin, the clansmen once harvested with scythes. They threshed with flails. The grain was eventually ground in hand querns. While all this was going on, the chief, it seems likely, was sitting around petting his black dog, perhaps at Dunevin, perhaps at his house in Kiloran. The black dog was a matter of some discussion on the island, because no one could understand why the chief wanted to keep it. The dog was lazy, would not hunt, and ate prodigious amounts of food. “Kill it,” said the clansmen, but the chief said no, the

day would come when he would be glad he had the dog.

From these beginnings emerged one of the most widely known legends of the Hebrides. It was said that the chief had been hunting in a remote part of the island when he came to a cottage inhabited by an old man who had a litter of pups, one of which, a black one, was so appealing to the chief that he said, “This dog will be my own.”

The old man said, “You may have your choice of the other pups, but you will not get that one.”

“I will not take any but this one,” said the chief.

“Since you are resolved to have it, you may have it,” said the old man. “It will not do you but one day’s service, but it will do that well.”

The dog grew to be large, powerful, beautiful, hungry, and—because it refused to hunt—worthless. Once, the chief arranged to go hunting on Jura, and he tried to take the dog, but the dog looked at the shore and the waiting boat and lay down and refused to move.

“Kill it,” said the rest of the hunting party.

The chief said, “No. The black dog’s day has not come yet.”

A forbidding wind came up and the hunt was postponed. The next day, the boat was prepared again, but the dog would not go.

“Kill it and don’t be feeding it any longer,” said the clansmen.

“I will not kill it,” said the chief. “The black dog’s day will come yet.”

The sky became violent and the expedition was postponed.

“The dog has foreknowledge,” said the clansmen.

“It has foreknowledge that its own day will come yet,” said the chief.

The next day, in clear and lovely weather, the hunting party, seventeen in all, got into the boat—everyone, the chief included, ignoring the black dog. Just as they were about to shove off, the dog ran down to the shore and leaped into the boat. “The black dog’s day is drawing near,” said the chief.

That night, in a cave on Jura, the chief’s sixteen companions were murdered by supernatural beings who tried to attack the chief, too, but were driven away by the ferocious black dog. Then the life of the chief was almost taken by a great arm and hand that reached down for him through a cleft in the ceiling of the cave. The black dog soared into the air and locked its jaws over the forearm of this monster and chewed it until the hand fell to the floor of the cave. The black dog went out and chased the bloodied monster away, then returned to the feet of the chief, lay down, and died. “Thig latha choindui fhathast” is a Gaelic expression that derives from this legend and is in common use. It says, literally, “The black dog’s day will come yet,” but in English it has been slightly corrupted into “Every dog will have his day.”

For putting that one over, I cannot help but feel affection for the chief, and it even makes forgivable, perhaps, his slipping the sword and the galley onto his tombstone and absurdly pretending to be a Lord of the Isles. I have on my living-room wall in Princeton a six-foot rubbing of his tombstone, elaborate with ivy, harts, and griffins; it is there because it always makes me smile. The chief in that particular incarnation was the one who died in the cave in Uragaig when the MacLean bowman shot him from above. An hour or so beforehand, he had been at his house, in Kiloran, when the invading MacLeans approached. Outnumbered, he left in a hurry with one of his friends, whose name was Gilbert MacMillan. They were running together up the side of Ben Sgoltaire when they looked behind them into the glen and saw thirty or forty MacLeans go into the house and come back out dragging McPhee’s screaming wife.

McPhee said, “MacMillan, why don’t you go down and see if you can do something to help her? She has been good to you, MacMillan. She gave you the stockings you wear. And you gave her good promises that you would see no harm come to her.”

“Unlucky is the time that you remind me of it,” MacMillan said, and he drew his sword and went back down the hill. MacLeans swarmed around him, but he stood with his back to a high stone wall and magnificently began to hack them down. Swinging and thrusting, he killed sixteen MacLeans, and he might have killed them all, but other MacLeans went around to the other side of the wall and pushed out stones at the base, making a hole through which they chopped at MacMillan’s legs until he fell. McPhee went on up the hill. One associates with one’s ancestors at one’s risk. I will never again be able to look a MacMillan in the eye.