1950 THE ROSE SEIDLER HOUSE / HARRY SEIDLER

AT A TIME WHEN AUSTRALIA WAS STRUGGLING TO FIND A NATIONAL ARCHITECTURAL STYLE, ALONG CAME THIS BRASH YOUNG MAN WITH AMERICAN TRAINING AND A EUROPEAN SENSIBILITY, WHO BUILT A RELENTLESSLY MODERN HOUSE IN THE INTERNATIONAL STYLE IN THE HEART OF SUBURBAN BUSHLAND.

The exterior mural was designed and painted by Seidler himself. The colours are repeated in the interior to link the two spaces – blue in the curtains, yellow in the kitchen and grey in the paint colours of the walls.

The cantilevered cabinet, which spans the rear wall of the living space, was made by Paul Kafka, a fellow immigrant from Vienna. The mix of timber, finished in matt black paint, and the reflective qualities of black glass is highly effective. Just visible in the reflection are the Grasshopper chairs by Eero Saarinen and the Calder-style mural.

The house that Harry Seidler designed and built for his parents in Wahroonga, on Sydney’s North Shore, was completed in 1950. It launched his career, defined the decade and caused a considerable stir. Not only did it excite the architectural establishment but it also attracted public interest in a way that domestic architecture rarely did. Visiting the perfectly preserved house more than 50 years later, it still feels daringly modern, so it’s easy to imagine the curious public who came all those years ago to gawp at the house that Harry built.

Harry Seidler was born in 1923 in Vienna, where he lived with his well-to-do parents, Max and Rose, in an apartment remodelled by avant-garde architect Fritz Reichl. With the Nazi occupation of Austria in 1938, Seidler followed his brother Marcell to England, and was taken as a refugee to live with two English ladies in Cambridge, where he attended school for 18 months after which he was interned, first in Liverpool, then the Isle of Man, before being transported to Canada. After his release in 1941, he gained a first class honours degree from the University of Manitoba before winning a scholarship to Harvard Graduate Design School.

The period at Harvard was to be a defining experience for him. Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus movement, and Marcel Breuer, a teacher and practitioner of the Bauhaus principles of design, ran the postgraduate course. Later, Seidler worked as Breuer’s chief assistant in his architectural practice in New York, studied design with Josef Albers (a former Bauhaus teacher) in the short-lived, but highly influential Black Mountain College, North Carolina, and spent a summer with flamboyant modernist Oscar Niemeyer in Brazil. All combined to ensure that by the time Seidler moved to Australia, at the behest of his parents, he had experienced an amazing exposure to the world’s most influential architects and teachers. At 25, his architectural mindset was confident, complete and ready to be exercised.

‘Rose Seidler House may look like a young architect’s house for his parents but really it is built manifesto, representing all the Modernist principles of Australia’s most famous modern architect…As an attention getter the house remains unbeaten. A homage to Seidler’s former New York employer Marcel Breuer, this house – with its TV-screen frontality, open pinwheel plan and elevated trapdoor entry – perches on the grassy site like an arrival from space.’ This remarkably astute quote from Elizabeth Farrelly’s article in The Sydney Morning Herald in 2005 sums up the house as a statement of intent.

At a time when Australia was struggling to find a national architectural style, along came this brash young man with American training and a European sensibility, who built a relentlessly modern house in the International Style in the heart of suburban bushland.

While the design came about with apparent ease, the construction was fraught with difficulty. There were problems finding a builder to undertake such a radical project, but with the help of well-established architect Sydney Ancher, Seidler appointed Bret Lake. In the postwar period, materials were not easy to come by and there are stories of Seidler driving around building sites picking up a few bricks here, a few bricks there.

Even the siting of the house was considered unusual. In an era where the front door inevitably faced the street, the Rose Seidler House is positioned in the centre of the block, with trees providing privacy and floor-to-ceiling windows opening the house up to bushland views.

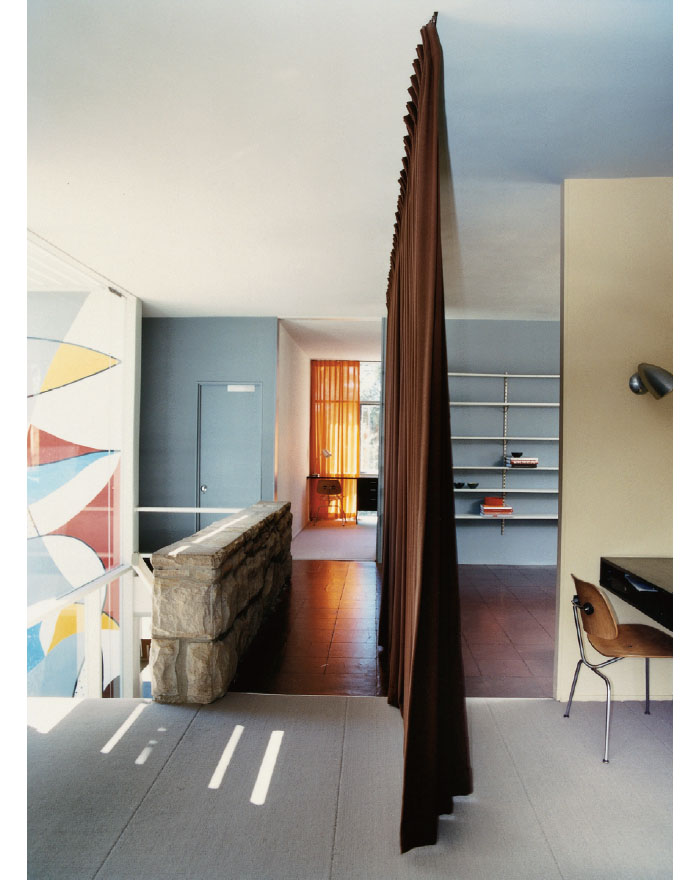

The fireplace, in rough hewn sandstone, is one of the few areas where the natural and haphazard intrudes into this precision interior. It also acts as a divider between the living and dining areas.

The dining table, made by Paul Kafka, is surrounded by plywood DCM chairs, designed in 1946 by Charles and Ray Eames. Between the dining area and kitchen is a sliding section of opaque glass to provide access to one from the other.

Looking along the cabinet to the bright orange wall of curtaining.

Such was the influence of Breuer that the house conforms to his binuclear layout, with one arm containing the public the – areas living room, dining room and the kitchen – and the other, the private ones – the bedrooms and bathrooms. Connecting the two internally is the playroom and, externally, a courtyard. Because there are few internal walls, and glass replaces external ones, there is a tremendous sense of openness. For flexibility, a dividing curtain ‘wall’ can be pulled across to segregate the living area from the playroom. Today, we are accustomed to this flow of one living space to another, but in the Fifties it must have seemed highly unconventional. A design factor the newspapers of the day picked up on was its elevation. Traditionally, houses were solid and grounded while this seems to float, supported by spindly legs and sporting a strange projection to one side – a ramp.

The reason this house has endured stylistically is due to the absolute conviction with which it was planned both inside and out. Take the colour scheme. ‘People who live complicated lives (and most of us seem to) cannot be comfortable in a highly colourful interior,’ said Seidler in 1954. It is a house where the use of bold colour, neutrals and earthy shades are held in perfect balance. The external mural sets the tone. Painted by Seidler himself, it recalls artists Miró and Calder, whom Seidler later collected, and captures all the colours used in the interior. There are cool greys on the walls, mid-greys in the carpet and deep brown upholstery on the sofa. The floor-toceiling curtains, which provide walls of colour when drawn, are bright orange, electric blue and dark brown.

This outdoor area is accessed via the ramp or directly from the living area. The colours and shapes in the mural are echoed in the choice of the famous Butterfly chair, the curvaceous form and solid-coloured canvas covers of which couldn’t be more apt. All the furnishing in the house is as originally specified and shows the architect’s ability to think in terms not only of the structure but also of the aesthetics of the interior.

The furniture is very much the epitome of mid-century excellence and was bought (along with the light fittings) in New York before he left, knowing that he wouldn’t get what he wanted in Sydney. Plywood DCM dining chairs, designed in 1946 by Charles and Ray Eames, were the result of wartime exploration into the potential of moulded ply. Combined with a chromed steel structure and exposed rubber shock-mounts, the look is industrial rather than domestic. The Eero Saarinen Womb chair (1948) and Grasshopper chair (1947) have a sculptural quality that is a pleasing counterpoint to the linear design of the living room. The much-copied Ferrari-Hardoy Butterfly chair in eyepopping yellow is aptly placed beside the mural where it looks like a 3D extension of the work’s black outline and infill of solid primary colour. The built-in furniture was designed by Seidler, but made by another Viennese immigrant, craftsman Paul Kafka. The cantilevered wall cabinet is a particularly contemporary execution, with its combination of black polished glass and matt painted wood suspended on an Atlantic grey painted wall.

The fireplace and balustrade in roughhewn sandstone are the only point in the precision interior where a sense of the randomness of nature intrudes, directly reflecting the exterior walls and the organic environment within which the house sits.

With materials hard to come by in this period, necessity proved the mother of invention. Seidler used galvanised piping for the handrail, and explored the possibilities of other new materials. The asphalt tiles in the playroom, while deemed less successful because of their lack of durability, have achieved a rich patina over time. Seidler’s experimental thinking was particularly successful in the kitchen. It was the last word in kitchen design in its day with House & Garden and Home Beautiful magazines wowing their readers with the cutting edge labour-saving devices, wipe-clean industrial stainless steel benchtops and coloured glass-fronted cabinetry. Not even the convention of handles was observed – simple circular cut-out shapes in the glass were enough. A Dishlex dishwasher, Crosley Shelvador fridge of grand American proportions, Kenwood Chef Mixmaster and Bendix front-loading washing machine ensured this ‘machine for living’ had all the necessary cogs in place.

While the bedrooms are small, they are well-equipped and reflect more intensely the colour scheme of the rest of the house. By extending the door cavities to ceiling height, and using sliding doors, the entrance to the rooms feels generous and the outlook onto nature, from every room, keeps them light and airy. In the master bedroom, a deep brown feature wall with flexible wall-mounted light, strong orange curtain, grey fake-fur bed throw and a simple black desk by Paul Kafka combine comfort, sensory pleasure and functionality.

In 1952, the Rose Seidler House was awarded the highest architectural accolade in Australia, the Sulman Medal. The significance is not to be underestimated, with the establishment having been seeking a style to call its own for so long. Seidler’s view, according to writer Donald Leslie Johnson, was that his architecture achieved ‘not only a total response to Australia but in complete sympathy, created out of the needs of Australia (society), the site (environment) and that it was logical (rational) and therefore suitable’.

While that may be open to debate, what is incontrovertible is that this house was visionary. So many of its concepts are now commonplace, from the importance of aspect and siting, open-plan living and the integrated kitchen to the painted feature wall, the cantilevered cabinet and insistence on well-designed furniture.

This, Seidler’s first commission in Australia, was as confident a statement as a young architect could make to establish his credentials, and laid the foundations for his career as one of Australia’s most eminent and enduring architects.

The Rose Seidler House is now the property of the Historic Houses Trust, NSW.

A solid yellow door sits in a wall of glass. The black desk by Paul Kafka is built in and cantilevered to give a light, open feel. The view onto the bushland beyond contrasts the linear measured quality of the interior with the randomness of its setting.

DETAILS THE ROSE SEIDLER HOUSE

WOMB CHAIR The Knoll Model 70 chair is better known by its nickname, the Womb chair, so called because a person could easily curl up in it in a foetal position Designed by Eero Saarinen, the Womb chair was an extension of Saarinen’s earlier collaborative work with Charles Eames for MoMA’s 1940 ‘Organic Design in Home Furnishings’ competition. Six years later, while working for Knoll, he chose to exploit the new medium of fibreglass instead of the earlier moulded plywood techniques pioneered with Eames. It is one of the earliest examples of using this material in furniture, but the rough finish needed to be fully upholstered to have an acceptable appearance. The Womb chair has been in continuous production by Knoll since 1948.

KITCHEN The kitchen purportedly cost more to fit out than the rest of the house. It was the last word in new domestic technology combined with easy-to-clean surfaces and cleverly built-in necessities such as the ironing board. The interiors magazines of the day were in awe of the Dishlex dishwasher and the Bendix front-loading washing machine, not to mention the huge scale of the American Crosley Shelvador fridge. Together with the stainless steel benchtop and cupboard doors of coloured glass, it presents a complete design solution to the functional kitchen. Rose Seidler entertained frequently, was an excellent cook and would have made good use of the cutting-edge amenities.

RUSSEL WRIGHT CROCKERY In keeping with Seidler’s furniture purchases for the house, the crockery is the ultimate in Fifties modern. While his mother had managed to retain her beloved Viennese tea set and nineteenth century silver cutlery, Seidler acknowledges he ‘wouldn’t allow my poor mother to have anything in the house not consistent with the religion: modernism’. He bought from America Russel Wright’s American Modern crockery and Highlight Pinch line stainless steel cutlery. These crockery pieces, now in the Museum of Modern Art collection, were an example of the affordable decorating aesthetic that Wright championed. Simple and durable with an appealing biomorphic form, they came in a range of mix and match colours. Seidler, a purist, opted for white.

DIVIDING CURTAIN The notion of flexible, as opposed to fixed, spaces in the domestic setting has been exploited in Japanese architecture with sliding screens for centuries. At this time in Australia, walls were fixed, rooms had an explicit function and the idea of a variable open-plan space was radical. In this plan the living/dining/kitchen is linked to the bedroom/bathroom area via a playroom zone. A floor-to-ceiling length curtain ‘wall’ sweeps across and can either extend the living area or create privacy between the bedroom and playroom. The division of public and private spaces is facilitated and enables a response to the changing needs of the occupants.

COLOUR SCHEME For what was considered a ‘white box’, there is a significant amount and a varied range of colour in the Rose Seidler House. Yet, because it is recurring, it never seems to jar. The brown painted wall is repeated in the asphalt floor tiles, a feature wall in the foyer, the dividing curtain wall and the upholstery on the sofa. Greys feature in carpets, bedspreads and painted walls while orange fabric curtains provide statement-making panels of vibrant colour, inside and out, when drawn in the evening. The colour scheme is at its warmest and most recessive in the bedrooms. The furnishing is spare – a wall mounted reading light, a side table and a Paul Kafka desk in the master bedroom – and each bedroom has an expansive view to the bush outside.

HARDOY CHAIR While credited to Jorge Ferrari-Hardoy, the ubiquitous Hardoy chair (commonly known as the Butterfly chair in Australia) was actually designed in conjunction with Antonio Bonet and Juan Kurchan. All three were partners in an architectural firm in Argentina. Their inspiration came from a nineteenth century British folding chair. Designed in 1938, the Hardoy chair rapidly became extremely popular and the licence to produce it was acquired in 1947 by New York furniture company Knoll. The bent metal rod frame is simple to manufacture and the chair was copied in large numbers. Loved for its loungey abstract shape, it expressed a freespirited modernism reminiscent of the work of Calder, Arp and Miró.

While the commission was for an American Colonialstyle house, Peter Muller delivered a confident design that owed a debt to the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Acknowledging the Wrightian influence, Muller was also very much his own man and the solutions he found resonated with the Australian landscape. The ‘snotted brickwork’ was an attempt by Muller to breathe some life and create some texture in the wire-cut bricks his client purchased without his knowledge.