1953 THE AUDETTE HOUSE / PETER MULLER

GROUNDED AND LOW-LYING IN THE LANDSCAPE, CONNECTED TO NATURE AND MAKING THE MOST OF WINTER SUN WHILE MINIMISING SUMMER HEAT, THE HOUSE IS CREATED IN MATERIALS THAT HARK BACK TO A MORE RUSTIC AGE.

The three-dimensional qualities of this house are instantly evident. The strong horizontal planes plus the contrast of solid mass with light areas of glass and timber give it a dynamism and strength.

While the interior has been considerably refurbished, the original exposed timber beams create a graphic statement. Their connection with the external timbers link interior and exterior visually by extending the eye from one space to the other.

As an architect, Peter Muller has Always run his own race. His innate affinity with nature and music has shaped his philosophical outlook and created a mindset that is as subtle as it is strong.

This house, in Sydney’s Castlecrag, is the first he designed as a qualified architect. As an early example of his work – he was only 24 at the time – it encapsulates many of the preoccupations and ideas that have endured throughout his long career.

Fundamentally, his architecture is known for an organic, romantic quality which works in harmony with its setting and exploits the inherent beauty of natural materials. He is particularly drawn to materials that are modified and enhanced by the passage of time – wood that weathers, stone that melds into the landscape, or copper that gains the patina of age.

While the Audette House is the start of a personal architectural journey for Muller it is also a highly significant house in the development of a distinctive regional Australian style.

Born in 1927, Muller grew up in the Adelaide suburb of Leabrook, where he recalls a semi-rural upbringing. A preference for the countryside over cities is something that has never left him and this longstanding connection to, and love of nature, was fostered by his mother, a keen gardener. He was also clear from an early age of the profession he would join. ‘When I was three years old, my mother says I wanted to be an artichoke when I grew up.’

Muller describes the School of Architecture at Adelaide University as more like a technical college. With a hefty dose of plumbing, carpentry and surveying on the curriculum, it lacked any contemporary context for architecture. So while Muller applauds the sound training in the practical aspects and technical knowledge of building he gained, he also admits that ‘…the consciousness of world architecture did not extend beyond the Greek orders’.

Muller was a quick and clever student, managing to complete a degree in both engineering and architecture in a record four years. In 1949 he moved to Sydney, took a stepping-stone job at Hennessey and Hennessey architects and set about applying to American universities for a place on a master’s degree course. Primarily he wanted to travel, and in 1950 was one of six postgraduate students to receive Fulbright Scholarships funded by The United States Educational Foundation. The University of Pennsylvania could accept him immediately (Yale and Harvard had one to two years’ waiting lists), and with his first class passage fully paid for, he set off.

Ironically, while studying in the States, he made no attempt to visit the buildings of the great practising architects of the day. ‘I never visited a Frank Lloyd Wright building. I never visited a Marcel Breuer building. I just went skiing instead,’ he says. In an encounter at the Harvard School of Architecture, the famous Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius quizzed him about Australia, and while Muller can remember him talking about architecture, he confesses it went in one ear and out the other.

A European trip followed – Denmark, Sweden, England, Italy, France and Switzerland – where his memories are of the food, the people, the countryside. For Muller it was the opportunity to soak up the atmosphere and experience new cultures.

In Paris he did pay a visit to one modernist icon. ‘I had a look at one of Le Corbusier’s buildings and decided I never wanted to see another as long as I lived…I was so shattered and disappointed, I found it so ugly and so bad in detail and so scungy…I never related to his philosophical or social views of architecture,’ he says. At this stage Muller may not have had a firm handle on his own philosophy, but he certainly had a highly developed sense of what it was not. On his return to Australia in 1952, two significant things happened. Taking a job at Fowell, Mansfield & Maclurcan to make ends meet, he met a young draughtsman called Adrian Snodgrass, who was to become a lifelong friend. In Snodgrass he had met someone of like mind who could stretch Muller’s natural field of interest. For example, he introduced Muller to the extensive works of Frank Lloyd Wright. Where Muller had reacted so negatively to the work of Le Corbusier, with Wright the connection was instant. The simplicity of materials, the love of nature and the harmonious relationship of a building to its site – Wright’s principles resonated with Muller’s natural leanings.

The second significant event was a commission that would launch his career and oblige Muller to develop his architectural philosophy and translate it into the three-dimensional. Mr Hauslabe owned the Ford car concession in Australia, and was chairman of the Fulbright Scholarship Committee. His stepson, Bob Audette, had bought a beautiful north facing block of land with Middle Harbour views in Castlecrag and wanted to build a family home. Mr Hauslabe’s thoughts obviously turned to the intelligent young architect the Fulbright Scholarship had sent to the USA a couple of years before, and reasoned that his Stateside sojourn would have taught him a thing or two about building an American Colonial house. Peter Muller was the man for the job.

Muller tells of laying out the plans on the bed of his tiny Kings Cross apartment and setting up a model he had made himself so that Bob Audette and his wife could walk around it. When they arrived, Muller excused himself to get cigarettes and left them to view the model and plans alone without undue persuasion. While it was nothing like the original commission of a Colonial house, on Muller’s return they agreed to build it, on the condition that it passed the CSIRO’s sun orientation tests. It succeeded on all counts.

The model reveals the architect’s original intent. The main wall was to be of rustic stone used in conjunction with Australian hardwood, treated only with linseed oil so that it weathered to a soft silvery grey. The combination of honest, unadorned materials was to ensure the house, set amongst angophoras, blended into the landscape. In this postwar period, access to building materials was still extremely limited and Muller admits to bitter disappointment when Audette seized the opportunity to purchase cheap, awful red bricks in lieu of sandstone for the façade. ‘It was my first house, so in hindsight I should have been more demanding,’ he says now.

In order to create texture in the brickwork, Muller came up with a series of innovative solutions. When laying the bricks, excess mortar was allowed to ooze out from between them. When it dried, it gave the wall a rustic appearance. In addition to this technique, which came to be known as ‘snotted brickwork’, random bricks were raised and slices of terrazzo were inserted. These elements combined to give Muller something of the organic feel lost by the failure to use stone, yet still delivered the form that he intended.

Although the land had no houses on either side, Muller experienced difficulties with its siting. A freeway was planned to run along the northern, water side of the block and so prevented him siting the house as far forward as he would have liked. Hence the Audette House has a strong street presence, unlike the ‘hidden’ siting of many of his subsequent houses. It is, however, not a mere façade – its three-dimensional quality is one of the defining aspects of the building. While it is grounded and integrated into the site, with the garage disappearing under the living area, it also has a dynamism and strength created by the bold use of horizontal planes floating above the rows of windows.

Muller’s plan was radical for the early Fifties. Most houses presented a flat façade to the street with the important rooms – the living room and master bedroom – at the front. Taking its cue from British housing, the rear of the house incorporated the service areas – kitchen and laundry – with little or no thought given to orientation, siting or access to outdoor space. Muller turned all this thinking on its head. What is now commonplace was then revolutionary.

The site for the house was a very beautiful one with a spectacular view. However when Mr Audette had bought the land, a freeway was scheduled to run along the north side of the block. Happily, this didn’t eventuate.

The house has many strong, graphic angles. Garden beds were integrated into the original design, such as this one which runs along the windows facing the street.

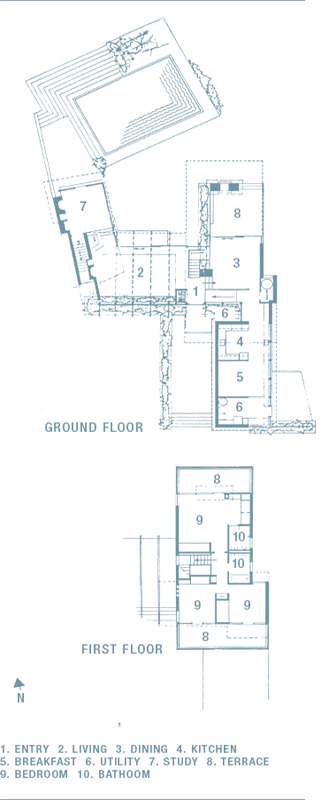

There are three strongly defined zones at ground level – the living/study area, the dining area and covered terrace, and the kitchen/breakfast and utility area. They are held together by the first floor bedroom/bathroom level which sits predominantly over the dining/terrace area but also links the other two zones.

There is a satisfying sense of forms echoing one another, of repetition and symmetry within the context of a limited palette of materials. Muller has always had an emotional and intellectual connection with music, particularly that of Bach, and this appreciation has given his work a distinctive rhythm.

The interior of the house has recently been altered but the essence of the plan has been retained. The main living area is large and open-plan, and connects through floor-to-ceiling doors, originally in timber, to a lawn terrace and pool beyond. Again, the Audette House was a significant departure from the prevailing arrangement of space, which tended to be boxy, compartmentalised rooms with little relationship to outside. Hence, the direct linking of interior and exterior spaces was ahead of its time.

Timbers running through the living area were extended beyond the glass to join their exterior counterpart and lead the eye from one space to the other. The U-shaped courtyard, pool and spectacular Middle Harbour views created a compelling vista.

Three years earlier, Harry Seidler had completed the Rose Seidler House – an uncompromising residence in the International Style which quickly became accepted as the defining form of modern architectural thinking. What Muller offered in the Audette House was a real alternative, an opposing architectural standpoint. Grounded and low-lying in the landscape, connected to nature and making the most of winter sun while minimising summer heat, the house is created in materials that hark back to a more rustic age. Yet the use of these materials was far from traditional. They were fashioned to create a fullyformed, dynamic aesthetic which enabled a contemporary way of living. It is easy to see the significance of this house and to understand why many architects drove along Edinburgh Road to view first-hand the work of this audacious young architect.

The Audette House is undoubtedly in line with Frank Lloyd Wright’s philosophies. Many of Wright’s architectural pillars are also those of Muller and he does admit to leaning too heavily on Wright for solutions to problems, rather than for the generation of ideas.

Interestingly, only two years later, Muller’s own house, on an awkward site in Sydney’s Whale Beach, had moved further from obvious Wrightian devices to take his fast developing philosophies to a new level. The integration of house and landscape allowed for trees to be incorporated into the living area and for rock formations to be preserved. Muller says, ‘I was living in the site as well as the house.’ It is this house that architectural historians see as his coming of age as an architect, and it is to this day Muller’s favourite house, but the Audette House is where the journey began, and for that it is worth celebrating.

DETAILS THE AUDETTE HOUSE

EXTERIOR TIMBERS For the exterior timbers Muller used an American product new to Australia. It contained, amongst other things, beeswax and linseed oil, and gave the wood a matt longlasting protective finish that was easy to maintain. The supplier he bought this product from formed the paint and finishes company Wattyl. The exterior woodwork was coated by later owners with marine varnish, giving the appearance it has today. Muller’s original finish would have gained a soft patina over time but he recognised that most people want to ‘scrape it back and remarine varnish it every two years to have that fresh, bright, clean look all the time’.

OPEN STAIRS Muller’s original design intent was to do away with the small boxy rooms prevalent in the houses of the early Fifties and open the space up in a new way. ‘I wanted to eliminate passages,’ he says. The staircase, with its open-tread construction, has a feeling of lightness and, as Muller points out, ‘allowed one to come in the front door and look completely through it’. The simple ‘hung’ design, achieved through the minimal use of painted steel, allows the staircase to become inconspicuous, as Muller intended.

SNOTTED BRICKWORK Muller still recalls how devastated he felt when his client Bob Audette bought a job lot of bricks to replace the sandstone intended for the external walling throughout. ‘They were wirecut bricks – a cheap, unattractive brick with striations,’ he says. In an attempt to bring the bricks to life, Muller devised a technique in which the mortar was allowed to ooze out from between them and harden. This became known as ‘snotted brickwork’. Certain bricks were also raised and sections of terrazzo introduced to give a rustic, textured feel to the walls. While it was a clever solution, it never satisfied Muller and he still wishes he had tried harder to talk Audette into using sandstone as planned.

EXPOSED RAFTERS ‘I always tried to expose the structure as a sign of integrity,’ says Muller. ‘By opening up the methodology of construction, there is less need for superfluous decoration.’ The exposed rafters in the living area are a strong, graphic element, and the link with the exterior trusses connects internal and external space. The use of a bolt fitting reinforces the sense of honesty, an aspect of Japanese and Balinese architecture that Muller admires. Originally the rafters were Australian hardwood, lightly treated but left their natural colour. but as part of a recent renovation, they have been stained dark grey.

THE ARCHITECT’S MODEL At the age of 24, Muller’s presentation of his model of the house was key to securing the commission from clients whose brief was for an American Colonial house. Showing maturity beyond his years, Muller didn’t try and talk his potential clients into the project but left them alone to peruse the model. The design differs on a couple of points. Most significantly lost was the rustic stone walled section on the right of the photograph and the long trough for plants which, in the original, fitted neatly under the windows. The trusses, which continued over the roof line, were built as per this design but were removed by a subsequent owner.

The exterior of Roy Grounds’ 1954 house is an exercise in simplicity. One side of a perfect square faces the street, an oversized door sits centrally and the high-set windows let in light while ensuring privacy. Inside, a cork-tiled wall divides the kitchen from the dining area. The US company Expanko, from which Grounds originally sourced the tiles, again provided imperial measure tiles for the restoration of the wall.