1954 THE GROUNDS HOUSE /ROYGROUNDS

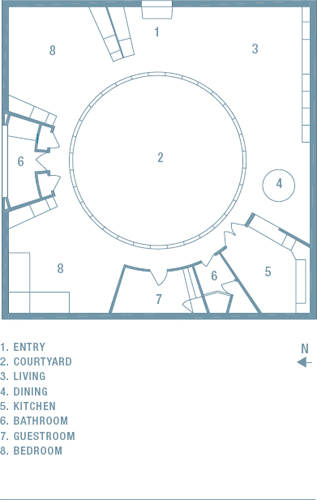

THE PLAN OF THE GROUNDS HOUSE TAKES GEOMETRY TO AN EXTREME, AND INVOLVES TWO PRIMARY FORMS – A SQUARE ENCLOSING A CENTRAL, CIRCULAR COURTYARD. TO THE STREET, IT PRESENTS AN IMPASSIVE FACADE OF IMMACULATE PROPORTION.

The circular courtyard set within an external square illustrates Grounds’ preoccupation with geometry. Thirty-two window or door openings onto the courtyard from the house reinforce the connection between the two spaces. Black bamboo acts as a shield from sun, as do the internal bamboo blinds.

All the cabinetry has been carefully reconstructed in accordance with the original drawings. A cupboard in limed Victorian ash divides the entrance from the bedroom area. This openness ensures a sense of continuous space. The cabinetry stops short of the windows, allowing that line to remain unbroken.

Sir Roy grounds was a distinguished and controversial figure in the postwar Melbourne architectural scene. He had a caustic wit, at times at his colleagues’ expense. He once said of his associate Frederick Romberg, ‘Freddy’s the grain of sand that irritates me to produce a pearl.’ From architectural concept to realisation, Grounds was a perfectionist, believing in the power of a single idea, masterfully executed. This award-winning house, built for his wife and family in 1954, is a prime example of his architectural preoccupations at the time, and is commonly viewed as a precursor to his best-known public building, the National Gallery of Victoria.

Even before the Second World War, Grounds began to establish a reputation for avant-garde thinking. He had travelled to London in the late Twenties with his college friend – and later partner – Geoffrey Mewton. From London, they moved to New York where they both worked in architectural firms: Grounds in a practice specialising in Collegiate Gothic and Mewton, at the other end of the spectrum, worked on skyscrapers. Grounds then moved briefly to Hollywood to join his wife, Virginia Marr, and turned his hand to designing film sets for MGM and making furniture in the Bauhaus style for LA’s design cognoscenti.

He observed the work of significant American architects practising at the time, such as Richard Neutra, Frank Lloyd Wright and the lesser known William Wurster, who was an exponent of the Bay Area Modern Style. This style emphasised the use of locally found materials with a continuity of indoor and outdoor space through the use of window walls.

In 1932, with his wife and their young son, Marr, he moved back to Melbourne where he designed his first house, known as The Ship, at Ranelagh, Mt Eliza. It had asbestos cement siding with rope handrails and a porthole window lending a nautical air to its seaside setting. The Ship and Mewton’s Stooke House attracted attention for their functionalist style, and in 1935 the RVIA (Royal Victorian Institute of Architects) recognised them as notable examples of inter-war domestic architecture. Praise indeed for architects barely 30 years old.

A series of houses designed in this period – the first Henty House, Portland Lodge in Frankston (1933–4), Lyncroft in Shoreham (1934), Fairbairn House in Toorak (1936) and Ramsay House in Mt Eliza (1937) – all show the influence of Wurster. Whether they fulfil Wurster’s criterion that a house ‘should be an unlaboured thing, that looks as inevitable as something that comes out of the frying pan just right, like an omelette in France’, remains to be seen. These are important buildings, with Robin Boyd describing the living room/ kitchen area of the Ramsay House as ‘the most important room of the century’.

In 1937, Grounds and his second wife, Betty, spent a year in France, but with the outbreak of war imminent they returned to Melbourne, where they moved into the Ramsay House.

The black slate table (ingeniously engineered to heat up) is surrounded by four MR10 chairs by Mies van der Rohe positioned at the four points of the compass. The hatch in the cork wall allows for easy access from the kitchen.

Grounds’ immaculate sense of proportion is clear from the exact positioning of the timber mullions.

During the war, Grounds was sought out for a new form of commission – apartment blocks – which were to confirm his reputation as one of Melbourne’s most notable architects. With a shifting demographic, there was an increasing demand for one- and two-person apartments. Grounds undertook Clendon (1939–40), Clendon Corner (1940), Moonbria (1941) and Quamby (1941) – all of which stand to this day. Here he explored the potential of continuous space, undertaking a considerable level of thoughtful detailing, including retractable ironing boards, fold-up beds and writing desks. The Grounds House in Hill Street is a projection of the line of development he first employed in the design of Quamby flats, also in Toorak. There, the walls form a gently curving arc, radiused from a point some distance from the flats.

Grounds joined the RAAF as a flight lieutenant during the war, and was involved in the construction of airfields and defence buildings. After a brief period of farming postwar, he was appointed senior lecturer at the University of Melbourne in 1948 and was involved in structuring the curriculum. He was a powerful influence on many of his students. Don Fulton, in particular, remembers ‘Roy said that a building should have “one simple, strong idea”’, a dictum which Fulton followed in his subsequent, award-winning works. Grounds appointed both Frederick Romberg and Robin Boyd as lecturers and, in 1953, they formed the famous partnership Grounds Romberg & Boyd.

Robin Boyd described Melbourne in the 1950s as ‘Australia’s cradle of modernity’, and it was certainly a period of intense experimentation for architects such as Peter McIntyre, Kevin Borland and Boyd himself. Shape and colour, technology and materials, combined with a certain theatricality of construction, all conspired to challenge the establishment. Grounds’ use of geometric shapes in plan-form is evident in the designs of the triangular (Leyser) house in Kew (1951) and the round (Henty) house in Frankston (1952). In fact, the completely circular Henty House ll was considered such an unusual building that those driving past it on the Nepean Highway referred to it as ‘the flying saucer’.

Early proposals for Hill Street featured three-storey apartments set behind the house. However, the Grounds House, which won the partnership of Grounds Romberg & Boyd the RVIA Architecture Award in 1954, is sited close to the street and was ultimately accompanied by a series of small two-storey town houses staggered behind it, following the slope of the land.

The plan of the Grounds House takes geometry to an extreme, and involves two primary forms – a square enclosing a central, circular courtyard. To the street, it presents an impassive façade of immaculate proportion. The roof is cantilevered with up-sloping eaves, and seems to float above the high windows set just below it. It is easy to see the influence this house seemingly had on Grounds’ design for the National Gallery of Victoria (1961–68).

A large front door has Grounds’ signature door knocker, and a Japanese maple stands to one side of the slate forecourt. The house is the perfect marriage of forcefulness and elegance, comparable to oriental architecture, where nothing is given away at street level, but also to Palladian architecture, where proportion is paramount.

Entering the house, one is immediately invited into the seemingly large, open living area. Thirty-two fullheight windows that form the circular courtyard wall admit an abundance of light. Each area of the house opens into the courtyard through glass doors. The space is continuous with few interior walls. Those that do exist are clad in vertical ribs of Victorian ash, and frame only the kitchen, bathrooms and children’s room. The precision of the design ensures that all joinery, mullions and fitments are set out on radial lines from the courtyard’s centre. Bedrooms are closed off by sliding doors, fingerpulled from radial slots, the edge of the door being cleverly disguised among the other ash ribs.

The house has not always been in the immaculate condition shown here. For many years, it was neglected, unloved and its basic design somewhat abused. Fortunately, it was bought in 2003 and painstakingly restored by cardiologist Dr Martin Hiscock. Through original drawings found in the State Library of Victoria, he discovered that architect Don Fulton, as Grounds’ assistant, had prepared the 1953 plans. He contacted Fulton, who has advised him throughout the restoration. Hiscock sourced original materials and skilled tradespeople, and also adopted a hands-on approach to the project himself. He carried out the painstaking tasks of stripping the ash mullions and doors of overly heavy liming, laying cork floors and installing aluminium acoustic ceilings in both bathrooms.

‘I was determined to restore the house back to its original intention because I think it should never have been allowed to have lost it,’ says Hiscock. ‘Too often we see architecturally important buildings “improved”…and the whole potency of the original and enduring design is lost.’

The living area has been furnished with design classics in keeping with the era. A pair of Barcelona chairs by Mies van der Rohe with a matching coffee table sit opposite a Florence Knoll sofa. The flamboyant zebra skin rug is a recent addition. Again, cabinetry in the original design has been reinstated along the wall.

Under Hiscock’s eagle eye, joinery was expertly reinstated by David Burke, using limed solid timber. Bathroom mosaic tiles matching the originals were found and individually hand-laid in brick pattern according to Grounds’ design. A large disc of black slate used for the dining table (the original having been removed from the house) was located in Genoa, Italy, and imported, not once, but twice, due to damage en route. And as per Grounds’ design, electrical cable is connected to heat the table in winter. Cork tiles of imperial dimensions from the original company, Expanko, have been used to re-tile the dining room wall with its ‘secret doors’, and the kitchen restored with the addition of modern appliances, underbench fridges installed and the cork floor returned.

The impressive hand-beaten and rivetted copper flue in the living room has not been replaced by Hiscock, although as with everything to do with the restoration project, he has tracked down its whereabouts. It used to smoke, and discolour the surrounding carpet with embers. One night, during a drinks party at the house, an unfortunate student was given the task of sitting on the roof to fan the smoke and try and increase the draw of the fire!

Heating was originally achieved with Pyrotenax cables laid in the concrete slab, but these had been interrupted over time. Reverse cycle air conditioners, hidden in the living room cupboards, now cope with temperature fluctuations. As architect and writer Neil Clerehan once remarked, the house is a ‘fascinatingly detailed treatment of climate and human scale’.

As the courtyard is visible from every room, the use of materials and plants contribute significantly to the ambience of the house. The original Silurian mudstone pavers in the central courtyard had been replaced with bluestone offcuts from the National Gallery open spaces. Hiscock resited the bamboo planting from the south to the north to help screen the living area from the sun. In addition, he removed an unsightly canvas awning and fitted bamboo matchstick blinds to the insides of the windows. On top of that, Hiscock commissioned Don Fulton’s son, Simon, to restore the paving to the forecourt.

The use of simple and natural materials, such as Victorian ash, cork, slate and lightly bagged brick walls, recalls the comment of Jennifer Taylor, who said of Roy Grounds’ work, ‘He combined rationalism and economical planning with a love of warm, natural materials.’ There is a Scandinavian feeling that recalls Alvar Aalto’s approach to interiors. Hiscock has returned the original aesthetic values of the Grounds House with due regard to heritage principles. Visiting the restored house last year, Lady Betty Grounds exclaimed, ‘Why, it looks just like new.’ And indeed it does. Having restored the original lustre to this architectural ‘pearl’, Hiscock reflects, ‘This house makes you wonder why we live the way we do, surrounded by four walls covered in Dulux. I prefer to be looking into a garden all the time, thanks; there is a lot to be said for inward looking.’

The Grounds House is celebrated and listed in the Victoria State Heritage Register and classified by the National Trust of Victoria.

The bedroom is one of the areas with a sliding door for privacy. The treatment of the mix of timbers, from the very fine ribs of ash to the timber-clad ceiling and the limed Victorian ash cabinetry, is resonant of a Scandinavian aesthetic.

DETAILS THE GROUNDS HOUSE

JOINERY The joinery Illustrates Grounds’ capacity for complete interior solutions. Sliding timber doors pull out from radial slots to divide off the bedrooms from lobby areas. Clever pieshaped ‘bin cupboards’, on each side of the bed in the master bedroom, and the toy box in the children’s room provide useful storage. Above, the floating desk is integrated with overhead bookshelves, which house hidden incandescent downlights. These have recently been reinstated, as per the original drawings, by skilled joiners Troy and Lindon Davey- Milne, who worked with David Burke. These limed Tasmanian oak joinery pieces are again set out on radial lines from the courtyard centre.

AWARDS A plaque on the house façade records the ‘RVIA Architecture Award Grounds Romberg Boyd 1954’. It was the first RVIA award, and Roy Grounds accepted it from the lord mayor on behalf of the newly formed firm. The house at 24 Hill Street was described by The Herald newspaper as ‘Victoria’s best new building’. The award was not given again until 1963, from which time it was presented as the Victorian Architecture Medal (Bronze). Grounds was later snubbed when, in 1969, a suburban shopping centre won the award over his great work, the National Gallery of Victoria, with the ceremony being held in The Great Hall of the gallery itself.

HANDLES The level of detailing is extraordinary in the Grounds House. Drawings of the courtyard door handles specified their manufacture in cast metal coated with a satin nickel finish, with hand grips of anodised aluminium tubing. They create an elegant sculptural shape, with outside mirroring inside, and folding back neatly when open into catches on the window mullions. All 32 glazed aluminium windows and doors are of the same dimensions, and each of the bedrooms and living areas open into the courtyard.

FOLD-DOWN BOARDS The kitchen, with its bagged brick walls, generous open wooden shelving and benchtops, and stainless steel sink area, is a clean, modern-looking space. Interesting details have been reinstated. Shown here is a fold-down chopping board referred to by Grounds as ‘fruit and vegetable flaps’. He used these in the 1940s in the kitchens of the Quamby flats, a project praised for its thoughtful detailing. The handles, by which these boards are pulled down into place, also form their supports in adding an extra useable surface. It is a good example of Grounds’ ingenuity and playfulness.

CORK Cork is used as flooring in the kitchen and bathroom but it is its use on the dining room wall that is innovative, acting as a backdrop to the circular, black slate dining table which is screwed into the concrete slab and wired for heating. The cork wall has a hinged serving hatch that Grounds referred to as ‘secret doors’. Hiscock reinstated these, cladding them and the wall in Expanko cork tiles. He found the original firm in the USA and imported them so as to be faithful to the dimensions on the drawing which are in imperial (6 inches x 6 inches). Hiscock acknowledges that this restoration project abounded with difficulty and was a ‘tricky job’ for expert joiner David Burke.

ROOF The original roof was of aluminium sheeting. This was an early use for what was to become a commonly used material for this purpose. Later, the aluminium was replaced with bitumen. The black bamboo can be seen projecting above the roof level. Encircling copper guttering is still in place, and has gained a rich patina over time. Grounds used black bamboo and bluestone pavers again in the courtyards of the National Gallery of Victoria.

The land on which Peter McIntyre built his experimental house in 1955 overlooks the Yarra River, Melbourne. Visible only in winter, the house disappears behind foliage from spring to autumn. The triangular shape of the house is carried through to the windows, and uncompromising colour is used throughout the interior.