1966 THE ROSENBURG/HILLS HOUSE / NEVILLE GRUZMAN

GRUZMAN WAS A PIONEER OF NEW TECHNOLOGIES, AND MUCH OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THIS HOUSE COMES FROM THE MANNER IN WHICH HE MANIPULATES SPACE THROUGH THE USE OF MATERIALS.

Gruzman was interested in new technologies and this pavilion in glass, timber and concrete illustrates some of his preoccupations. The house originally comprised a bedroom and bathroom mezzanine at entrance level and a large open-plan living area of double height, as shown, on the lower level.

‘I really dislike gruzman because he is the most aggravating, demanding, sometimes impossible person I have ever known – nothing is ever done well enough to satisfy him – he is concerned for reaching for the stars…the result is that he has given me two heart attacks, caused me to have a quadruple bypass and in the end will be the death of me.’

It was with these words that Neville Gruzman himself opened his talk (Gruzman on Gruzman) to the members of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA). It was his way of acknowledging his reputation for being difficult to deal with; his way of letting them know that he knew.

This lecture, conducted entirely in the third person, explained something of his past. ‘Gruzman grew up in the Depression – as a result he had a depressed personality – he will never throw anything away.’ More poignantly, the stresses of the Depression are said to have killed his father, a Jewish immigrant, who, with Gruzman’s mother, ran a pub in the Sydney suburb of Matraville. ‘Gruzman’s widowed mother set out to bring up her three sons on a tiny income, ensuring that they got love, affection and a good education,’ he told his audience. However, he was later to acknowledge the lack of a male role model, and felt fortunate to have a series of significant influences which helped to fill this gap.

Neville and his brother Laurence converted to Anglicanism and went to Sydney Boys High School. Subsequently, his time at the University of Sydney was a mixed bag. ‘I was a lousy student and I struggled through third year,’ Gruzman once said. The acting dean went so far as to tell him he would never make it as an architect. With a typical spirit of defiance he thought, ‘I’ll show the bastard.’ And then, what Gruzman describes as a miracle happened in the form of the Hungarian lecturer, cartoonist and architect George Molnar, who had arrived in Sydney fresh from the modern movement in Europe.

Up till then, the study of architectural history had concluded at the end of the nineteenth century and so, until Molnar’s teaching, there had been no mention of the work of Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe. Molnar’s Point Piper flat became a place for discussion, debate and the drinking of red wine. ‘Molnar would settle in a chair he designed himself – set himself up like a little god – and espouse architectural philosophy,’ Gruzman recalled. His eyes were further opened by his friend and contemporary, Bruce Rickard, who introduced him to the work of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

As a student, Gruzman also found pleasure in attending the freehand drawing classes of eminent artist Lloyd Rees. The tide in Gruzman’s relationship with architecture was turning, and another piece of good fortune was to come his way. An aunt was creating a subdivision of waterfront land at Rose Bay and part of the condition of sale was that her nephew, the architecture student, was to design the house. He later admitted this was rather daring on her part. The resulting house, influenced by Le Corbusier, was such a success that the builder asked him to design a house for himself next door. Suddenly the student, who graduated in 1952 and was expected not to make it as an architect, had two waterfront homes to his name by his fourth year of study.

An epiphany of sorts occurred in Sydney’s The Craftsman Bookshop in 1955. He came across a book published the same year called Architectural Beauty in Japan, picturing the Ryoan-ji sand garden in Kyoto. So deeply felt was his reaction to what he saw that he promptly abandoned his practice and, at the Japanese government’s invitation, moved to Japan for four-and-a-half months of study. The Ryoan-ji sand garden didn’t disappoint. The effect of its beauty was ‘transporting’, and he saw clearly that ‘architecture is more than putting together space and material; there are heights that we as creators can reach’. He praised the Katsura Imperial Villa for its spatial qualities, particularly the relationship of inner and outer space, and level of detailing.

Once he returned to Australia, Japanese architecture had an enormous impact on his work – the use of materials, the level of craftsmanship and the intellectual rigour all shaped Gruzman’s sensibility. He went so far as to announce that post-Japan he was a ‘born-again architect’.

Working on Sydney’s North Shore in the 1950s and 1960s, he produced a number of houses that reflected his natural flamboyance. There’s a theory that because his style was hard to pigeonhole, and he didn’t adhere consistently to any particular school of architecture, he has received less recognition than he deserves. Gruzman himself was of the opinion that his buildings had no obvious signature, that each project was answered with its own set of architectural solutions dictated by the site and needs of the client.

Indeed, a snapshot of three houses built around the same time show his diversity. The Salz House, in Rose Street, Mosman (1960), uses unadorned clinker brick in a strict linear design recalling the work of Frank Lloyd Wright; the Holland House in Middle Cove (1961) is a modernist cantilevered structure, predominantly built in glass and timber, and is restrained and geometric, while the Chadwick House in Forestville (1961–64) is an organic cave-like dwelling constructed of a series of interlocking hexagons using bush stone. Bruce Rickard, however, points to their similarities. ‘They all have a beautiful spatial flow, the living areas all face north and they are exquisitely detailed.’ Whatever the style, these buildings all have the panache of their creator; as Peter Watts, director of the Historic Houses Trust, said of the houses, they are ‘one-off major gestures, very Hollywood glamour’.

The bookshelf and wall cabinet are where the kitchen was once sited. The original cantilevered cabinet was in stainless steel and illustrates Gruzman’s forward thinking in his early adoption of the open-plan, one-wall kitchen. The pair of Wassily chairs by Marcel Breuer, to the left, are where the dining table would have been situated. The mirrored pillar houses plumbing pipes and electrical cables and was originally glass fronted to expose the inner workings, and partially painted to form a ‘vertical sculpture’.

The remarkable sculptural fireplace and stairway is the centrepiece of the room. Its gravity-defying structure illustrates something of the bravado that characterises Gruzman’s architecture. This view is from the lower level of the dining area, through the stairs to the living space and out to the bush. Concrete was formed to make a platform for the sofas, which were originally covered in black and white ponyskin.

Two aspects of Gruzman’s architectural philosophy are outlined in Australian Style, a book written by Babette Hayes and April Hersey in 1970. The first is to do with siting for maximum sunlight. ‘Even in the brief winter months the admission of the winter sun can do more than merely supplement other forms of heating…its sense of warmth can be developed by the architect when he encourages it to push deeply into the space to paint the interior with its pale golden light.’ The second is to do with privacy, and he talks of ‘that increasingly elusive quality of privacy, now almost lost to us, privacy visually and privacy audibly’.

The issue of privacy would have received a thorough exploration for Gruzman while designing the Rosenburg/Hills House on Sydney’s upper North Shore. His bachelor client, Sam Rosenburg, was a practising naturist and wanted to be able to ‘wander around his house nude’, said Gruzman. Not something, one suspects, the rather conservative suburb of North Turramurra would approve of. Rosenburg had read a Sydney Morning Herald article by Gruzman on architectural education, and commissioned him to build his home on that basis alone.

The large site sits at the end of a culde-sac, overlooking a gorge. Gruzman, who had also studied landscape architecture, created a sense of arrival by designing impressive semi-circular walls at the entrance from the street and a long driveway curving down to the house. He built a series of hills which screen the approach to the house, and created a dramatic waterfall, the sound of which fills the air. This planned environment formed the perfect context for the house.

Gruzman was very attuned to the land he built on, and the setting for the Rosenburg/Hills House is incredibly dramatic; perfect for an architect whose work is described by Professor Philip Goad as ‘theatrical and performative’. Overlooking this majestic bushland view, the house itself seems to settle with a light touch on the land. Constructed of glass, timber and concrete, it echoes rather than mimics a Japanese aesthetic. It also, as Goad points out, ‘brought together two iconic twentieth century houses (Wright’s Fallingwater, and Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House) to create the ultimate diagram of abstract shelter in the landscape’.

Gruzman was a pioneer of new technologies, and much of the effectiveness of this house comes from the manner in which he manipulates space through the use of materials. Walls of glass are intersected by a roof line which butts into the interior; double-height pillars give a monumental sense, and the central sculptural fireplace, integrated into the staircase, is engineered to appear to defy gravity. It is a house without a bad angle, inside or out; it is highly photogenic.

The front door is large and imposing for a house that is more like a large-scale pavilion. At entrance level is a bathroom and bedroom open to the amazing view. Downstairs is a large dining and living area. Three sides are glass, and the rear wall, which is solid, originally supported a cantilevered stainless steel bench which constituted the kitchen. Today, the one-wall kitchen, open to a larger room, is commonplace but in 1966 it was a radical way of approaching the lifestyle requirements of his client. It recalls one of Molnar’s cartoons for The Sydney Morning Herald, showing two rather hoity-toity ladies with the caption, ‘We don’t eat in the kitchen, we cook in the dining room.’

It was Gruzman’s view that ‘outside spaces are often rightly regarded as extensions of inside spaces’, and the concrete platform that extends from the living area faces north, guaranteeing daylong sunlight. The linking of indoor and outdoor space is strengthened by the use of concrete in both areas – a material that Gruzman felt was organic, and connected readily to the landscape.

When designed in 1966, it had a bold interior created by the famous Australian decorator, Marion Hall Best. The carpets were bright red, the sofas ponyskin, the mullions were painted dark crimson, and Marcel Breuer Cessna cantilevered chairs sat around the Eames Aluminium Group dining table. This avant-garde approach was also matched by Gruzman touches – a square, glass-faced pillar that housed the plumbing for the bathroom was originally painted various colours by Leonard Hessing to create, in Gruzman’s words, ‘a vertical sculpture’.This was a seriously cool, designer bachelor pad set amongst the gum trees.

The original owner only lived in the house for a few years before his death, and it fell into rather unsympathetic hands. Many of the attributes that made it great were either covered or corrupted. Besser blocks and beaten copper panels were a crude attempt to create privacy, and although the new owners sought Gruzman’s advice, he didn’t take up the challenge.

Thankfully, the next owners, Michael and Kerrie Hills, who bought in the early Eighties, appreciated the good bones beneath the vulgar add-ons. Not only did they set about restoring it but, with the needs of their growing family in mind, contacted Gruzman with a view to a substantial addition. Gruzman came to ‘interview’ the Hills in their rather conservative house in Sydney’s Beecroft and agreed to take on the project. Later, at a pre-arranged meeting at the Turramurra house, he was more than an hour late. Upset by the neglect he was aware it had suffered over the years, he had forgotten its exact location and got lost.

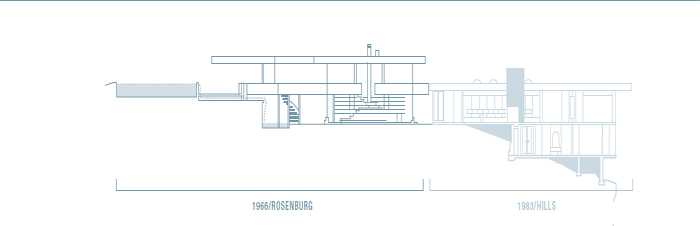

Space had been left on the site for an addition and, in 1983, it was built, complete with a truly spectacular bathroom. As John Haskell in his article on Gruzman for Art & Australia points out, ‘The house therefore combines Gruzman’s work over almost 20 years and again shows his remarkable consistency of style.’

Part of the reason Gruzman produced such successful houses is attributed to his ability to connect with his clients, to take on not only their practical living demands but also their personal traits and attitudes and mould them into a very personal building. The Hills had a long and pleasurable relationship with Gruzman. ‘He was always generous with his time and would discuss the most minute details with us, sometimes over hours,’ says Michael Hills. He acknowledges frustrations but senses that Gruzman, having regretted compromising in the past, simply didn’t want to do it anymore. In his quest for perfection, cost was never an issue. As Kerrie Hills astutely points out, ‘Neville needed patrons, not clients.’ But the Hills do credit Gruzman with opening their eyes to a different way of seeing things. ‘He was opinionated but always spent the time to talk it through,’ says Michael Hills. ‘He was widely read and extremely knowledgeable. He got us young and made us part of the process.’

In Gruzman’s own Darling Point home, glamour played a central role. The bathroom alone speaks volumes. A completely mirrored space, it allows for endless, faceted reflections – leading more than one journalist to draw the analogy between it and the multi-faceted nature of Gruzman’s personality. As well as an architect, he was for many years the very vocal Mayor of Woollahra, in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, and a dedicated university lecturer, giving generously of his time to students, beyond the call of duty.

Conversely, he was a highly successful litigant and in almost 50 years had taken 30 cases to court. This is only matched by the staggering number of times the accident-prone Gruzman was admitted to Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital – 40 times in 30 years.

Over the years, the written word became increasingly important to him and, holding fast to the view that ‘architects have a responsibility to the built and natural environment’, nothing much escaped his eagle eye. The standards he set for himself he also expected of others, and more than once was reprimanded by the RAIA for the public criticism of the work of fellow architects.

His personal life appears highly charged and passionate and yet in his work he found inspiration in the principles of Japanese architecture, striving to create serene buildings that harmonise with their surroundings. As Professor Philip Goad said, ‘His work, like his personality, was chimerical, brilliant, outspoken and assertive. You could not divorce the two.’ Through a lack of compromise comes a reputation for being difficult. Through lack of compromise also come great buildings.

The concrete used internally is extended out to form a north-facing platform. Gruzman considered concrete an organic material which connected with the landscape. It is also an extension of his philosophy of relating the house to the land, and siting for maximum sunlight.

DETAILS THE ROSENBURG/HILLS HOUSE

STAIRCASE Gruzman’s passion for Japanese architecture did not limit his concepts to the handcrafted or low-tech. Instead, he embraced the principles and married them with his own interests in engineering and with technological advances in the use of glass, steel and concrete. The integrated staircase and fireplace in the Rosenburg/Hills House is a case in point. Here, Gruzman has combined functionality with a dramatic sculptural centrepiece. An engineer friend who had worked on Centrepoint Tower in Sydney’s CBD visited the house, looked at the staircase and said, ‘What’s holding that up?’ The very open hearth gives the sense of a campfire in the way the wood is arranged and adds an elemental touch to a very sophisticated interior.

WATERFALL Gruzman’s idea for this house was to maximise privacy. Visually this was achieved by the man-made hills (the client acquired earth from local roadworks) which were constructed along the approach to the house from the street, with some being up to 10 metres high. Gruzman was also sensitive to ‘privacy audibly’, and the inclusion of a waterfall within the grounds creates a completely secluded environment where nature can be seen and heard. At night the bushland animals, including possums, wallabies and large goannas, wander onto the concrete platform.

FURNISHINGS Within his glass pavilion, Gruzman was anxious to give his client a sense of enclosure. One of the ways he did this was with the symmetrical placement of the sofas on the formed concrete platform. The platform doubles as a step-up to the doors, again illustrating Gruzman’s virtuosity in streamlining the functional needs of a space. Originally, as part of interior decorator Marion Hall Best’s scheme, the sofas were covered in ponyskin, and the floor covered in a bright red shag pile carpet. The contrast with the raw concrete was bold but very effective. The ponyskin sofas have been replaced with Antonio Citterio Diesis sofas customised to fit on the concrete slab.

DOORS The elegantly proportioned floor-to-ceilling glass doors open onto the north-east facing cantilevered concrete platform. The doors, with their fine window mullions and predominance of glass, create a minimal barrier between the interior and exterior, and the consistent use of concrete makes the transition seamless from one to the other. Gruzman was passionate about sensitive siting to maximise sunlight, which was particularly important in this case, with the client being a naturist.

EXTERIOR LIGHTING Gruzman’s words best describe his approach to the exterior lighting scheme. ‘I always use lighting in gardens so that at night they almost become part of the interior space. In this project I did something quite different. By concealed lighting around all of the edges of the roofs, I actually provided almost all of the internal lighting by reflecting it from outside to inside through the glass walls. The effect of this was at night to allow the occupants to live in a large pool of light that [combined] inside and outside as one.’ By day, siting makes the most of natural light, while by night the lighting scheme is another device to unify interior and exterior.

MIES VAN DER ROHE MR40 The MR40 by Mies van der Rohe was one of a line of metal framed cantilevered chair designs that he worked on from 1926–31. This particular model was a reworking of the earlier MR20 chair which was manufactured by Thonet with either a textile or a woven cane seat. The MR40 added luxurious rolls of padded leather to an already extremely comfortable design. ‘You will be sitting on a column of air,’ the Bauhaus catalogues boasted of the cantilevered concept. Contemporaneous to Mies van der Rohe’s experimentation with tubular metal cantilevered chairs, Marcel Breuer, Mart Stam, Hans Luckhardt and Anton Lorenz were producing their own versions. The chair has been produced by Knoll International since 1953.

Set on a battleaxe block amongst angophoras, the Bruce Rickard house sits into the hillside. Built in sandstock brick and timber, it blends seamlessly with the landscape. An original light detail in the living area.