1972 THE BUHRICH HOUSE II / HUGH BUHRICH

THE DOMINANT FEATURE IS THE INCREDIBLE WAVE CEILING WHICH GIVES AN ORGANIC, EXPRESSIONIST FEEL TO THE ROOM. CEDAR BOARDS WERE STEAMED TO MAKE THEM PLIABLE, AND THEN BUHRICH NAILED EACH ONE INTO PLACE.

The open-plan living and dining space incorporates built-in elements which Buhrich designed himself: the sofa, dining table and storage cupboard, with ponyskin-covered chairs inspired by the Breuer Long Chair.

Behind the timber textured wall is a concrete panel which appears to float in its glass surround. The waved roof line and ceiling add to the sensuous quality of the house.

There are some houses that just stay with you. They capture your imagination the first time you see them and they live in the back of your mind forever.

In the Nineties, I was a devotee of British Elle Decoration, edited by the inspiring Ilse Crawford. Each month would deliver a mix of British and overseas stories that satisfied my growing appreciation of architecture and interiors. One memorable issue, in 1998, showcased the Buhrich House ll in Sydney’s Castlecrag. Architecturally there was a lot to absorb: the undulating wave roof line, the fire-engine red bathroom and the awe-inspiring setting. When I pictured this book on Australian modernist architecture in my mind’s eye, this was one of the houses that defined it.

It was therefore with a sense of genuine excitement and curiosity that I made my way along Castlecrag’s Edinburgh Road in search of number 375. The road is wide and impressive and has a broad range of architecturally interesting houses, such as Peter Muller’s Audette House and fine examples of Walter Burley Griffin’s work. At one stage, the road narrows to a lane and I think I have run out of numbers when, at the very end, at the very tip of Sugarloaf Point, there are some stone steps cutting through a low bush garden. And there, as described by architect Peter Myers, sits ‘easily the best modern house in Australia’.

Architect Hugh Buhrich’s path to this, his final destination, had been far from straightforward. Born in Hamburg in 1911, he had a difficult and disadvantaged childhood, made no easier by the suicide of his father on returning from the Russian front after the First World War. Buhrich is on record as being rather disparaging about the quality of his education, describing the Munich architectural school he attended as ‘not very good’ and completing his degree at ‘a really shocking university’. On a more positive note, he worked in Berlin for Hans Poelzig, a prestigious architect with an enormous breadth of work, from the Poelzig Building at the Goethe University (1931) to large-scale set designs for film, including the 1925 production of The Golem. Fortuitously, also studying under Poelzig was Buhrich’s wife-to-be, Eva. The circumstances leading up to the war pushed the couple around Europe – to Holland and then briefly to London where they were married, finally arriving on Australian shores in 1939. After a short-lived, shared architectural appointment in Canberra, war broke out and Buhrich joined the army. His son Neil recalls his father’s time as a private in the Citizen Military Force (1942–45). Not trusted with real weaponry and trained with a wooden gun, he did, during games of chess and soccer, make lifelong contacts with fellow émigrés, who later provided the lion’s share of his architectural commissions. Educated central Europeans, many Jewish, went on to become successful, and turned to their architect friend when any kind of building was required.

After the war, Eva embarked on a long writing and editing career that included architectural criticism, under her own name and several male pseudonyms, for House & Garden magazine. Eventually she wrote a column for The Sydney Morning Herald. Her writing work provided financial support, and her outgoing personality enabled the couple

The view from the living room.

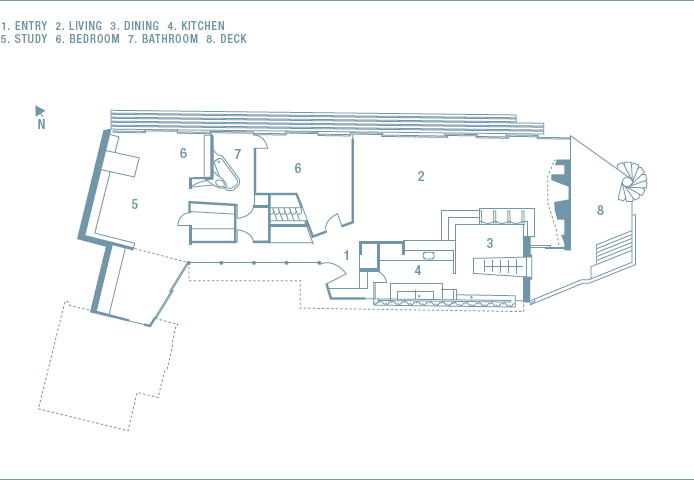

The dining table is positioned on a raised area with the kitchen adjacent, accessed to the right of the table behind the bank of cabinets. The wallhanging is a piece of carpet customised by Buhrich to soften the appearance of the suspended concrete panel behind it.

The compact kitchen with its simple bank of built-in cupboards is enhanced by the beauty of the wave ceiling and the natural light it allows into the room.

to have an interesting social life that included artists Robert Klippel and Francis Lymburner. The Buhrichs also hosted discussion groups attended by immigrants intent on continuing the cultural life they had left behind in Europe.

What must have been a great disappointment to Buhrich was the refusal of the Board of Architects to recognise his qualifications and, in doing so, denying him the right to practise officially as an architect. ‘The Buhrichs must have been somewhat nonplussed by the refusal, especially as the equivalent body in the UK, the RIBA, had clearly recognised them as a talented couple, and helped support them financially to make the trip to Australia,’ comments Peter Myers. For many years Buhrich worked under the title of ‘planning consultant’ and much of his work was restricted to alterations and interiors. Neil Buhrich recalls his father sitting for the exams and while he passed on the technical specifications part of the test, it was the design component that caused his rejection. His ideas were perhaps too radical for the conservative mindset of the Board of Architects in the 1950s. In 1971, it gave him the acknowledgement that would have been so useful earlier in his working life. As a result, apart from a few synagogues, small business premises and car parks, there are no major public works to speak of.

He did, however, design around 20 domestic projects, many of which are now altered beyond recognition or demolished, but it is the house he built for himself, and pretty much by himself, between 1968 and 1972, that has become the enduring testimony to Buhrich’s creative genius.

This ‘intensely personal’ project took four years to complete because most of the work – the hand cutting of sandstone, steaming and shaping of cedar for the ceiling, and designing specific pieces of furniture – was undertaken by himself and his assistant, Bill Chambers. There is a strong sense of a complete vision both externally and internally.

The house is built as an extension to an old Walter Burley Griffin structure which had been used as a fisherman’s cottage and was bought with money received as reparations from Germany. Set on a difficult site with an incredible view, Buhrich’s house settles into the landscape with a lightness that is both subtle and unassuming for such a remarkable building.

Buhrich was 57 when he designed this house, so it was to some degree the culmination of his ideas and influences. He had been a long-time admirer of the work of Ernest Plischke, an Austrian émigré who, like Buhrich, had fled Europe. He set up a practice in New Zealand and was also refused registration with the local architectural body, but was fortunate with his patronage and built some interesting houses. Thoroughly steeped in European culture, Plischke considered ‘the aim to be to achieve a synthesis of the conception of space and sculptural quality. Each of these two components must be evolved out of the function and the construction of a building.’ Although Buhrich was much more plain speaking and would not have chosen these words to express his vision, this philosophy is embodied in the Buhrich House ll.

The last interview Hugh Buhrich gave before he died was with architectural critic Elizabeth Farrelly, for Architecture Australia. In it he explained in plain and practical terms how many of the sculptural elements, particularly the roof and ceiling, came about, and, indeed, they were the result of ‘function and construction’. But there is too much ingenuity and beauty for one to be the mere result of another. The main living space is large and open, 10 metres by 7 metres. One wall of glass faces northeast, to the impressive view across Middle Harbour. The interior palette is natural – a mix of smooth black slate flooring, silver ash veneer for cupboards, hand cut local sandstone for the wall that houses the fireplace, cedar boards for the ceiling, and concrete for the wall. There is nothing special in this combination in itself; it is how it is used that makes it extraordinary.

The dominant feature is the incredible wave ceiling which gives an organic, expressionist feel to the room. Cedar boards were steamed to make them pliable, and then Buhrich nailed each one into place. They have stood the test of time remarkably well. Facing the bush is a ‘floating’ concrete wall inset with slim steel columns to provide support. The concrete wall is partially obscured inside by a carpet customised by Buhrich with a dark red wave pattern running through it – a subtle echo of the ceiling above.

Years of designing furniture for clients enabled Buhrich to integrate most of the furniture needs of the house into the overall plan. Very few extra items were needed and so the interior retains a completely resolved feel. The dining table sits on the slightly raised back platform of the living area. Its simple structure of a metal bar with acrylic ribs supporting the smoked glass top gives the appearance of being barely there. Where the table meets the rough sandstone wall there is a picture window, precisely the same width, which serves to extend the eye-line along the table’s surface to the bush outside.

The study area faces the view and shows another of Buhrich’s furniture designs – the built-in desk. He favoured the Eamesdesigned chair, the DCM, in the dining area and also here at the desk. OPPOSITE: Wood panelling creates a corner for a double bed; the door leads directly to the bathroom.

Wood panelling creates a corner for a double bed; the door leads directly to the bathroom.

The kitchen, accessed by the raised dining area, is compact but open to the larger living space. A bank of 15 press-open cupboards in silver ash veneer provides the divide between the kitchen and living space in a functional but sculptural way. More sculptural than functional, however, is the external staircase. Precast in concrete, it extends from a narrow deck outside the living area to the level below. Neil Buhrich points to his father’s dislike of bureaucracy and there is something rather rebellious about this precarious twisting, turning, open-to the elements staircase.

One of the most remarkable aspects of this already remarkable house is the bathroom. Nothing quite prepares you for it. Lulled by warm, organic shapes and natural tones, the fire-engine red bathroom in seamless fibreglass takes you completely by surprise. Again, Elizabeth Farrelly’s article quotes Buhrich’s practical view of its genesis. He had been boat building in fibreglass and was familiar with its properties. He didn’t like fussy bathrooms but did like occasional strong colour. He presents it casually as though there was no other conceivable outcome of this set of parameters. With a large, uncurtained window to the view, nature is part of the decor and this combination of the highly man-made within a natural context somehow makes it all the more effective.

Buhrich has described this house as his ‘most intensely personal’ project and it hopefully would have gratified him to learn that in March 2006 it was named ‘Building of the Decade’ for the 1970s by a panel of RAIA judges. The architect refused registration all those years ago had designed a building which not only garnered much international acclaim (French critic Françoise Fromonot described it ‘a truly radical building’), but has now been embraced as one of Australia’s most defining domestic residences.

The bright red fibreglass bathroom is something of a tour de force in a house of natural toned materials. The floor-to-ceiling windows ensure that the view – the trees and the water – creates a natural element in this extraordinary man-made space.

DETAILS THE BUHRICH HOUSE II

WINDOW AND TABLE Every element of the house was designed, created and crafted by Buhrich himself. This corner of the dining room encompasses many of the home’s features. The rough-hewn sandstone wall gives an organic feel, but is broken by the precision of the window. The glass table top, supported by acrylic ribs that almost disappear, allows the eye to skim along the table to the window and enjoy a framed view of the bush beyond. The wallhanging, which looks like an artwork is, in fact, a piece of carpet that Buhrich himself customised to soften the appearance of the concrete panel when looking from inside out.

MATERIALS The Buhrich House uses a mix of materials in a highly inventive way which creates textural interest inside and out. This exterior wall is designed to disguise the concrete slab, and its threaded timbers imbue the building with a handcrafted feel. There is a balance at play of the natural and the artificial. The precision of the glass dining table contrasts with the handcut stone wall, while the fibreglass bathroom, the steamed cedar ceiling, the precast concrete and the customised wallhanging play with a variety of materials. Interestingly, they were all the product of Buhrich’s creative sensibility, and it is to his great credit that these seemingly disparate materials hang together in such a cohesive and compelling fashion.

RED BATHROOM The bright red bathroom is an unexpected shot of exuberance in a house of earthy materials and natural colours. The use of fibreglass was a result of Buhrich’s experience with boat building. The plasticity of the material allows for shapes to be moulded, and permits everything, from the shower and the soapdish to the bath and basin, to be integrated into a seamless design. The floor-to-ceiling windows with the treetop and water views mean the room is open to the elements, emphasising the contrast of man-made shapes and bold colour with the nature beyond.

KITCHEN The kitchen is incredibly small by today’s standards and was tucked away between the storage cabinet shown (above right) and the back wall of the house. The windows under the undulating ceiling ensured it was light, but the compact nature of the space meant that everything had to have its place in order to operate efficiently. For example, the pots and pot lids were stored on the wall on small wooden pegs that acted as hooks or props. Sliding timber veneer doors and built-in kitchen cabinets gave the small space an integrated feel that blended into the overall scheme.

CEILING Many of Buhrich’s architectural solutions were, he claimed, the result of a range of practical considerations. The wave ceiling came about while working through a strict set of building height regulations. In Buhrich’s own words: ‘It was just a practical response: I decided to push the ceiling up between the trusses.’ The result is increased northerly light and, almost incidentally, an incredible expressionistic undulating ceiling. Inbuilt cabinetry, sofa and dining table ensured that the space needed little additional furniture. The fifteen-section cabinet (shown above) is in itself sculptural and divides the kitchen from the living area.

STAIRCASE While the Buhrich house is located in a bush setting on a spectacular piece of waterfront land, the interior and exterior are not connected in the way many of Buhrich’s contemporaries sought to link the two spaces. Outside the floor–to–ceiling windows in the living room is a narrow balcony made of planks, purely for the practical purpose of cleaning the windows, and the access from this space to the floor below is via a daringly constructed external staircase. Precast concrete sections were configured in a dynamic spiral which, due to the lack of a handrail, creates a sense of adventure when descending it.

Blending into the silvery greys of the surrounding bush setting is the holiday house of celebrated Australian photographer David Moore. Designed by architect Ian McKay after several false starts, the outcome has been described as ‘a thoroughly modern masterpiece’. The tonal palette for the house is partly inspired by the much admired angophoras.