1975 THE KESSELL HOUSE / IWAN IWANOFF

THERE IS NO DOUBT THAT THE MATERIAL IS INTRINSIC TO THE BUILDING’S INTENT. THE CONCRETE FEELS ORGANIC, BECOMING WEATHERED OVER TIME, WHICH LINKS IT WITH THE LANDSCAPE.

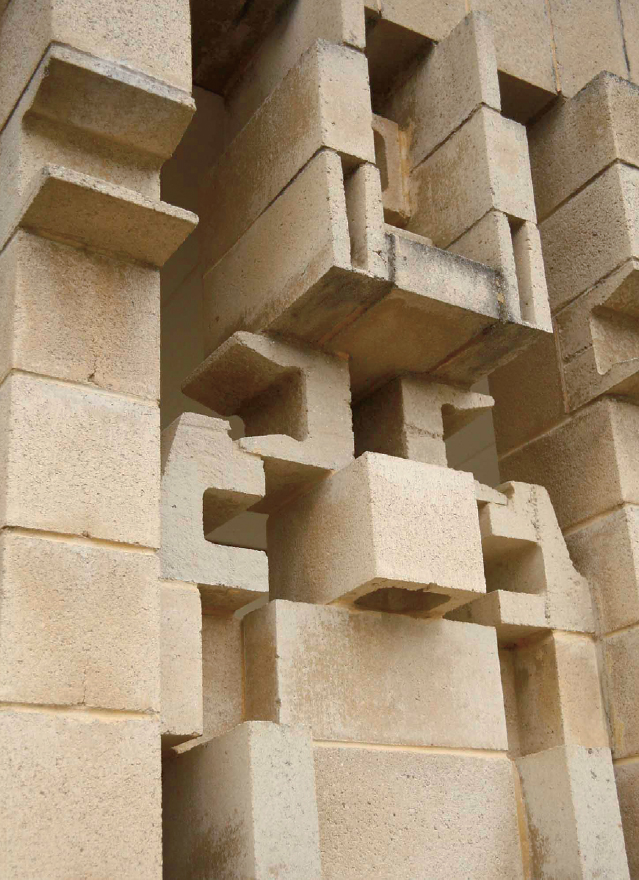

The design of the approach to the house has a sense of gravitas. The blocks create asymmetrical columns on either side of the steps – formal and repetitive on the left and intricate and totemic on the right.

The monochromatic door sports graphic black Perspex lozenge shapes. Sitting on the hall cabinet is a sculpture by Iwanoff’s friend and fellow Bulgarian, George Kosturkov.

‘We would take that despised outcast of the building industry – the concrete block – out from underfoot in the gutter – find a hitherto unsuspected soul in it – make it live as a thing of beauty – textured as the trees.’ These words were spoken by the great American architect Frank Lloyd Wright in the Twenties as he considered the structural approach he would take for client Alice Millard’s second house. Wright came up with an ingenious system in which precast concrete blocks interlocked, while the surface of the blocks created pattern and textural interest on the building’s façade. Fifty years later, this concept was to resonate with the work of Perth-based architect Iwan Iwanoff, who also found beauty in the concrete block. Not all the 200 or so projects he designed in his career were built from this material, but it is the work for which he is best remembered.

Iwan Iwanoff was born in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1919 and studied architecture during the Second World War at Munich University. His artistic sensibility was expanded by the course’s strong emphasis on drawing, sculpture and design, and balanced by classes in structural engineering, which honed his practical skills. In the foreword to the exhibition catalogue The Art of Architecture – The Architectural Drawings of Iwan Iwanoff (1919–86), Iwanoff expert Duncan Richards points out, ‘It was focused on training based upon a body of well established traditional design procedures and craft skills. The ultimate aim of the training was to develop and internalise semiautomatic “intuitive” judgments of visual order and visual coherence.’ And what emerges strongly in his later work is this combination of crafted detailing within a rationalised structure. ‘In my practice, the most exciting thing has always been the relationship between art and architecture,’ Iwanoff said. His sketches of proposed buildings for clients were loose and lyrical with all the seductive powers of a romantic portrait. His plans, on the other hand, were intensely detailed, with every architectural element carefully delineated and described.

After working in a Munich architectural practice between 1948 and 1950 with Emil Freymuth, Iwanoff took the radical step of moving to Australia with his wife, Linda. Initially, he worked as a labourer in a local Boral factory which produced precast concete blocks until, through Bulgarian community connections, he met architect Harold Krantz. Krantz had a reputation for assisting migrant architects with the complexities of adapting to their new culture and, in many cases, hired them to work for his practice, Krantz and Sheldon. As with other migrant architects featured in this book, the Board of Architects was often reluctant to recognise qualifications gained overseas, and careers could be stunted as a result. Apart from a year with Melbourne architects Yuncken Freeman in the early Sixties, Iwanoff was employed by Krantz and Sheldon until the mid-Sixties when he was legitimately able to establish his own practice, The Studio of Iwanoff. However, right from the outset, Krantz had agreed that Iwanoff could undertake private projects, and his first independent commission was completed in 1951.

Much of Iwanoff’s success came from his dedicated approach to clients and their requirements. He did not initially impose his views, instead learning as much as he could about what was wanted and how their lives operated. In his own words, he would ‘swallow…more or less…and digest, and digest and digest…once you have all this the rest comes automatically’. The outcome would be a home that would more than satisfy his clients, and his reputation for empathy and understanding brought additional commissions. In this instance, Dr Kessell and his wife approached Iwanoff on the recommendation of a previous client, Dr Kessell’s sister and her husband, Esther and David Schenberg, who owned an Iwanoff-designed house in Floreat, Perth. (The Schenbergs also commissioned a second house and a commercial building.)

Initially, the Kessells were not keen on the idea of a concrete block house but Iwanoff was able to persuade them of its appropriateness. It is a house that Iwanoff himself had earmarked as significant and it would gratify him to know that the original concrete façade is still intact. To his great disappointment, many of the exteriors of his blockwork houses were subsequently painted, which he felt ‘ruined the play of light’ and turned them into ‘something harsh and banal’.

There is no doubt that the material is intrinsic to the building’s intent. The concrete feels organic, becoming weathered over time, which links it with the landscape. The decorative element created by blockwork is subtle, in the one soft shade of grey, while the interplay of solids and voids gives it sculptural depth. When painted, the surface becomes precise and delineated, robbing the building of its quiet power.

Like Wright before him, Iwanoff sought to transform this everyday building material, with its connotations of industry and economy, into something richly textured and beautiful. In the decade since he built his own concrete block house (1965–67), his use of the material had become more elaborate and the Kessell House is a fine example of his ability to balance intricate decoration within the context of structural restraint.

His detailed plans left nothing to chance but the nature of the building work was intense. It was very different from the more conventionally constructed houses of the day, requiring specialist tradespeople who understood they were involved in the creation of something out of the ordinary. Iwanoff was known for his passion for his work, his hands-on approach and ability to infuse both clients and colleagues with enthusiasm. He told Duncan Richards the touching story of paying an unscheduled visit to a building site on a Sunday, where he found the builder proudly showing his wife and children the quality of the work he was doing there.

In the Kessell House, Iwanoff creates an intriguing sense of approach to the front door. The house is set back from the street behind a low tapering wall that follows the fall of the land. Steps from the driveway lead to a walkway and another set of steps leads to the porch, which is flanked by asymmetrical supports – one of simple square concrete block columns, the other totemic and complex. Set into a surround of glass panels in the deep porch is a boldly black-and-white patterned melamine door. Welcome to the world of Iwanoff.

The Kessell House is a large, single storey, four-bedroom family home arranged in an L-shape. To the left of the entrance is the bedroom arm, complete with a dressing room and study, both adjacent to the master bedroom. Three additional bedrooms, another bathroom, a laundry and a rumpus room at the rear (with access to the swimming pool) have all been accommodated in this section. To the right of the hallway, in the more public area, is the living room which contains a spectacular signature Iwanoff bar. Iwanoff’s personality has been described as gentle, shy and friendly but his work, as this bar reveals, has all the hallmarks of exuberance, with its carved pelmet, circular lightwells and the dramatic cutaway curve of the bar itself. Professionally he was no shrinking violet.

The movement through an Iwanoff house is designed to sustain interest. Richard Black, in his article ‘Eastern Block’ for Monument, observes Iwanoff’s ability to manipulate interior space. ‘There is also a spatial character to the houses that is derived from the use of continuous flowing space to unify the living areas. This would be modulated by screen partitions, built-in cabinet work and sometimes through the articulation of the ceiling and floor plane. So the living areas have a permeable quality where one is always aware of adjacent spaces and activities, avoiding the feeling of separation that would have resulted from traditional walled-in rooms.’

A case in point is the sculptural timber room divider separating living and dining spaces. Another Iwanoff pièce de resistance, it is designed with a cabinet at floor level to anchor the unit and visually balance the speaker boxes that sit on either side of an integrated air conditioning unit at ceiling level. Perspex was a favoured material and the black sliding door on the cabinet provides a sleek contrast to the timber. Alongside the bar, this piece is the hero of the house in terms of dramatic impact, but throughout the less public rooms, more subtle joinery is employed. It has been recorded that the detailed interior execution cost more than the building shell itself.

The bar area is a tour de force of sculptural elements. The cutaway pelmet houses a fluorescent light which, through the five circular holes, illuminates the area below. The back wall of the bar has a sliding screen which opens up to access the kitchen behind.

The elaborate room divider goes some way to explaining why the cost of the interior joinery exceeded that of the building shell. Iwanoff mixed timber veneer with his favoured black Perspex for the base cabinet, and increased the functionality of the unit by housing air conditioning and audio speakers in the upper section.

This close-up section shows the level of design detailing in the cabinet.

As observed by architectural writer Ian Molyneaux there are ‘sunscreens, stairs, balconies composed in an abstract expressionistic, sculptural manner, requiring an enormous amount of supervision by the architect’. Iwanoff’s commitment to the building as a whole, inside and out, meant that the project was fairly protracted and there were many on-site revisions. In addition to specifications for built-in furniture, there was wallpaper and curtains to consider, and Iwanoff accompanied the owners to help them choose items that would enhance the overall scheme.

His commitment to his projects and perceptive approach ensured enduring relationships with his clients, often visiting them and contributing ongoing ideas for their houses. When Iwanoff joined a group of architecture students on a tour of his houses in 1983, Duncan Richards, who was present, recalls, ‘What came across so strongly was the pride and pleasure of the owners in their collective efforts with the architect in creating these homes.’

The deep veranda, facing the street, is designed to help keep the house cool. Two Hardoy Butterfly chairs sit comfortably in the space.

DETAILS THE KESSELL HOUSE

CABINETRY Iwanoff’s European sensibility, his love of craft and passion for sculptural form manifested itself inside his buildings as much as out. This decorative room divider is functional in as much as it separates the living and dining area, and houses shelving, an air conditioning unit and speakers. It is also highly decorative and expressionistic in its form. Tenders for the interior joinery were sought separately to the building shell and were custom-made to Iwanoff’s detailed specifications. Preferred timbers were red elm and Tasmanian oak, and the design combined solid timbers with fine timber veneers used for the curved sections.

VENTILATION Unusually, the Kessell House was air conditioned at a time when few domestic residences had this luxury. In addition, Iwanoff used other cross-ventilation devices to ensure the house remained cool in the hot summer months. In the large window walls, he employed a series of Perspex panels that acted as vents at both ground and ceiling level. Originally there was a pond by the front door and the idea was that sea breezes would pass over the water and cool air would come into the house via the system of vents. The deep porch also created an area of shade.

GEORGE KOSTURKOV Sculptor George Kosturkov also came from Sofia in Bulgaria, where he studied at the Academy of Art. In 1968, as a young man of 26, he moved to Australia. Working primarily in bronze, aluminium, copper and stainless steel, he initially produced small-scale works but gradually, as his reputation grew, he undertook large-scale public and private commissions. Kosturkov was a close friend of Iwanoff and, looking at their work in parallel, it is not hard to understand a meeting of creative minds. Kosturkov’s work has a natural fit within Iwanoff interiors and the owners of the Kessell House have bought five Kosturkov sculptures, three directly from the sculptor.

PRECAST CONCRETE BLOCK Iwanoff’s use of concrete blocks was highly inventive and, as Duncan Richards points out, his work illustrates an ongoing interest in ‘organic expressionism’. The blocks used were all existing components created, generally, for a variety of commercial building needs and it is the ingenuity of Iwanoff’s approach that makes their combinations so effective. In particular, the Kessell House utilises areas of plain block with areas of intricacy so that solidity and lightness are held in perfect balance. The blocks are a sandy limestone colour and remain unpainted as Iwanoff intended.

ARCHITECTURAL DRAWINGS In 1991, an exhibition, The Art of Architecture – The Architectural Drawings of Iwan Iwanoff (1919–1986), was curated by John Nichols and Duncan Richards from the collection held by the State Archives of Western Australia. The fine arts remained an intrinsic part of Iwanoff’s approach, with the exhibition illustrating his mastery of drawing skills, from the university thesis he produced on a proposed chapel in the Bulgarian mountains through to one-off domestic residences in the Perth suburbs. It is interesting that when he set up his own office in 1964, he did so under the name The Studio of Iwanoff, showing his connection to the disciplines of art and sculpture as well as architecture.

From the street, the wedge and block construction of the timber-clad Kenny house is evident. The exposed bracing of the internal doors emphasises the honesty that characterises Kenny’s approach.