INTRODUCTION

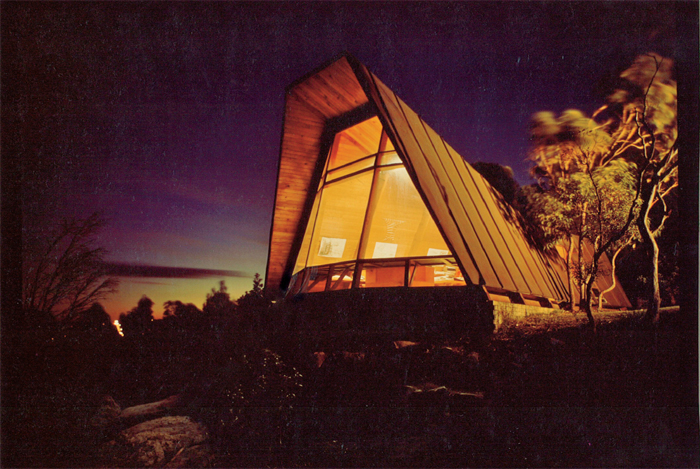

The McCraith House was designed by Melbourne architects Chancellor and Patrick. A compact holiday house in Dromana, a coastal town outside Melbourne, it illustrates the preoccupation with geometry prevalent at the time. Originally decked out in primary colours, it was later painted a more muted shade.

Many of today’s new houses are designed with a level of indulgence and luxurious use of space that could not have been imagined 60 years ago. Media rooms, multiple bathrooms with spa-style fittings, music rooms, in-house gymnasiums and swimming pools were once the territory of the rich industrialist rather than someone in middle management. Hence it is hard from this position of prosperity to conceive of the level of limitation Australians experienced in the postwar years. Nothing was thrown away nor taken for granted. Clothes were handed down, furniture was fixed, food continued to be rationed – the ‘mend and make-do’ mentality pervaded every aspect of life.

The war years (1939–45) were particularly grim for the architectural profession, and many small firms closed through lack of work. Materials were scarce and domestic buildings were subject to strict guidelines in terms of expenditure and size. The maximum floor space allowed was 14 squares (135) and an Australian Home Beautiful editorial in 1942 pointed to maximum costs of £3000 for a new house and a ceiling of £250 on renovations. These restrictions continued in the postwar years and, because of thedesperate need for housing with the wave of new migrants and the numbers of returned servicemen, the drive was often for quantity over quality. Aesthetics tended to give way to economics as the state controlled the entire process; the architects, engineers, designers and town planners all fell under one great bureaucratic umbrella.

An estimated 400,000 homes were needed, and to solve the housing crisis, the government looked both to local and overseas companies for quick-to-assemble housing. The Commonwealth Government (in conjunction with private enterprise) undertook a fact-finding mission to Europe to source the most suitable housing options, and subsequently bought prefab housing from Sweden and Great Britain. In his book Australian Architecture 1901– 51, Sources of Modernism, Donald Leslie Johnson notes that ‘probably the largest order for English prefabs came from the Australian government when it purchased a batch of factory made timber dwellings called the Riley-Newsum house as late as 1951: cost of 1,250,000 pounds sterling. Made in Lincoln and shipped to Australia in a series of panels.’

Set out in neat quarter acre suburban blocks, these houses had few of the refinements of previous decades, as Jennifer Taylor describes in her essay ‘Beyond the 1950s’: ‘The design features that had made the bungalow such a suitable building type for the 1930s and 1940s could no longer be achieved under the restrictions. “Luxuries” such as eaves, porches, verandas and fireplaces disappeared. In its stripped down form the Australian house had few redeeming qualities.’

The arrangement of rooms also reflected a bygone era. The living room and master bedroom faced the street and corridors led to a separate kitchen and dining room, while the rear of the building housed the bathroom and laundry with access to the yard. Basically, the plan consisted of boxy rooms with little thought given to either the relationship between them, or to the link between indoor and outdoor space. Orientation was a given – the house faced the street regardless of sun or site.

While this was true of the broad sweep of development, there were exceptions. It was a time where young architects felt a sense of opportunity to build a better world and there were ingenious plans by some, working within the restrictions, to maximise the sense of space by losing wasteful corridors and opening up kitchen and dining rooms to one larger area. Notable is the Beaufort House, designed by Arthur Baldwinson in conjunction with the Beaufort Division of the Department of Aircraft Production, which was shown in prototype to the public in 1946. Using technology developed for aircraft manufacture, this steel– framed house was an innovative attempt to contribute to solving the housing problem. The Vandyke Brothers in Sydney also provided local product with, amongst more traditional designs, the Sectionist house, created in 1946.

‘Australia is the small house. Ownership of one in a fenced allotment is as inevitable and unquestionable a goal of the average Australian as marriage,’ wrote architect and architectural critic Robin Boyd in the preface to his 1952 book, Australia’s Home.

He also noted that ‘it was said that flats were for foreigners.’ And, indeed, Australia was becoming home to many émigrés.From 1947, Australia was open to British residents but, despite considerable uptake, it was recognised that without further substantial immigration, the country would not flourish. Agreements were made with Malta in 1948 and Italy in 1951, followed by Greece in 1952 and Hungary in 1956. It is estimated that by the end of 1956, more than 1.5 million immigrants had arrived on Australian shores, all within the confines of the White Australia Policy. Promotional material targeting houseproud immigrants showed photographs of an immaculately maintained suburban bungalow and garden with the caption, ‘Australians…like to take refreshments out of doors and cultivate neat gardens.’

THE SPIRIT OF THE FIFTIES

The arrival of the Fifties, with its increasing economic prosperity, brought a breezy optimism and a strong consumer drive. Putting the hardship of the war years well behind them, Australians wanted the latest in mod cons, fridges, cars and a new style of home that reflected the spirit of the times. Magazines such as Australian Home Beautiful and House & Garden drove trends and influenced opinion.

It was the beginning of the marketing of a ‘lifestyle’. For a society that had made do, the desire for this new, shiny, ordered suburban life was irresistible. It is therefore understandable that the state-of the-art kitchen at the Rose Seidler House, with its cutting-edge appliances, caused as much excitement as the radical building itself. Advertisements in magazines illustrated Cary Grant and Grace Kelly look-alikes, with two perfect children, perusing plans and a model for their new house built in Hardie’s Fibrolite under the heading ‘Don’t Dream…Build’. The Age RVIA Small Homes Service in Melbourne, launched in 1947, with Robin Boyd as director, showcased a range of 4 architect-designed plans for new homes which could be bought for £5. Public uptake was such that by 1951, they were providing plans for 10 percent of all new housing in Victoria. From 1957, plans were also available at the Home Plan Service Bureau at the Myer Emporium, Melbourne, and in 1962, Lend Lease’s Carlingford Homes Fair in Sydney proved popular to the tune of two million visitors eager to see the latest in architect-designed project homes. Standard house plans were even published alongside knitting patterns in The Australian Women’s Weekly. Clearly, the public had taken Hardie’s call to action in their Fibrolite advertisement to heart. Australians were no longer dreaming…they were building.

A NEW APPROACH

Postwar was a period of staggering creativity and originality in Melbourne. There was a spirit of invention in the air as new ideas were generated, new materials and technologies explored and individuality celebrated. A handful of architects worked with site and client to realise exuberant schemes and one-off solutions.

Roy Grounds, who had enjoyed a very successful career before the war, championed a geometric approach to architecture. On the other hand, younger architects experimented with shape and materials in daring ways – Peter McIntyre, for instance, built his own house, a radical A-frame steel structure, with infill panels of Stramit, a compacted straw sheet material. Necessity is the mother of invention and a shortage of materials saw the introduction of lightweight steel frames and, as in Kevin Borland’s Rice House, a series of thin concrete-sprayed shells. Cantilevered balconies and window walls; cable supports and plywood ceilings; colour and form; playfulness and theatre – the confidence of experimentation knew no bounds.

A newly found affluence resulted in an increased interest in the holiday house. At one end of the spectrum was the commission from extremely cultured clients John and Sunday Reed for architects McGlashan and Everist to design a house right on the sand at Aspendale, a suburb outside Melbourne. At the opposite end of the scale, advertisements incorporating plans appealed to home builders to buy sheeting material and construct simple beach shacks themselves.

A corner of Bruce Robertson’s first house for his family in Sydney’s Seaforth (1953). The opening ply panels increased ventilation in this west-facing area of the home.

The interior of a Sydney Ancher house in Sydney’s lower North Shore suburb of Neutral Bay (1957) shows open-plan living to a degree that was considered revolutionary. The treatment of the ceiling adds a graphic quality to the space.

Another prominent architect designing beach houses (as well as country properties and city residences) in the Fifties for wealthy Melbourne clients was gentleman architect Guilford Bell. He trained in London in the 1930s where he worked on a house restoration project for author Agatha Christie. His 1952 design for Sir Reginald Ansett’s Hayman Island resort exposed Bell’s refined aesthetic to a range of potential clients. Working mainly as a sole practitioner (he had a brief partnership with Neil Clerehan in 1961 and later, until Bell’s death, with Graham Fisher) on domestic residences, his signature modern elegance found full expression in the Fairfax Pavilion (1969) designed for art collector James Fairfax in Bowral, NSW, and the Seccull House (1972), in Brighton, Victoria. In both, the excellent working relationship with the clients encouraged a freedom of expression, resulting in exceptional examples of Bell’s work.

Brisbane architecture firm Hayes and Scott designed the Harvey Graham Beach House in 1953 with its notable geometric murals. International journals were a great influence on Australian architects and the Case Study Houses of Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen could well have been a source of inspiration for this mural.

Melbourne’s virtuoso performance was, however, short-lived. As Peter McIntyre admitted, it is hard to make a living out of radical thinking but, for this period, Melbourne was, as Robin Boyd said, Australia’s ‘cradle of modernity’.

TESTING POPULAR TASTE

In Sydney an early and influential pioneer of modernism was Sydney Ancher. He had spent several years in Europe in the early-to- mid Thirties and returned to Australia filled with enthusiasm for the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. ‘In designing my houses, I think I have Mies at the back of my mind,’ he said. In 1937 he designed what is now considered one of Sydney’s most important prewar buildings, the Prevost House, for his architectural partner Reginald Prevost and family. His career went into a holding pattern when he went to war but, upon his return in 1945, he took up where he had left off, designing domestic buildings in the International Style. Ancher’s experiences with local councils are significant in that they reveal something of the prevailing attitudes towards the new thinking in architecture. The1945 design for his own house, Poyntzfield, in Killara, Sydney, was only approved by council after he altered the original plan for a steel-framed building to a more traditional brick construction with a pitched roof. It still won the Sulman Medal in 1946.

Neil Clerehan’s house for his family (1957) in Fawkner Street, South Yarra, Melbourne, shows the use of Stegbar’s window wall to full effect.

‘I WAS A MAD MODERNIST FROM 1934. HARD LINE AND HARD CORE, MY MOTHER GAVE ME A SUBSCRIPTION TO AUSTRALIAN HOME BEAUTIFUL, AND I WOULD TAKE PUBLIC TRANSPORT AROUND MELBOURNE SPOTTING THE MODERNIST HOUSES THAT I LIKED.

Ten years later I met Robin Boyd who was my sergeant in the army (he was an extraordinary influence on me) and when I told him of all the houses I had admired, it turned out they were all designed by the one firm – Grounds and Mewton. We were very envious of Americans at the end of the war. Because of the building boom, there were lots of opportunities to design contemporary houses. I admired the work of Neutra and Ellwood although both were slightly stand-offish in person. There were all sorts of difficulties obtaining materials in Australia. Getting plain, coloured laminate was like getting a drink in the Prohibition, and the ‘cream Australia policy’ was in full swing – you just couldn’t get white appliances. I did make the pilgrimage to Sydney to see the Rose Seidler House when it was finished. It did amaze me, but seemed somehow unrelated to Australia.

I was impressed with all the Eames and Saarinen furniture he was able to get from the USA.

I took over from Boyd in 1954 as Director of The Age Small Homes Service [Clerehan is at present the newspaper’s longest standing contributor], which provided plans to young couples who couldn’t afford custom-built but wanted a modern housing solution. During that time I encountered a tremendous range of people. There was a wave of immigration and sign language became very useful!

The training and discipline of thinking small was of great use to me when I designed a project house of 10 squares [93m2] for Pettit and Sevitt called the 3130 house which was a great success both in Victoria and NSW.

The so-called “Nuts and Berries” school in Sydney did have an effect on me – it softened me – but these days I am back to white precision. It allows people and furniture to stand out in a room.’

The second battle with council in 1946 was more serious, and groundbreaking in its outcome. Ancher designed a house for Mervyn Farley on a magnificent headland site at North Curl Curl. It was a small open-plan house with an extensive terrace (external space was not counted in the size restrictions and so it made sense to exploit it as much as possible) and elegant cantilevered concrete roof extending 1.5m beyond the walls. Warringah Council objected, but agreed to pass the design if a parapet 600mm high were put in place to disguise the flat roof which was considered an ‘affront to decency’. The case went to the Land and Valuation Court of NSW. Speaking for the appeal was eminent architect and writer Walter Bunning, while W.R Roach, Chief Health and Building Inspector for Warringah Shire, spoke against it. Roach commented that the building was ‘not pleasant, too stark and very different. More like a gun emplacement on North Head than a house.’ Despite the reactionary views, the appeal was upheld, the flat roof was vindicated and Australia could join the rest of the world in adopting this signature feature of the modern movement. It did not inhibit councils continuing to object on aesthetic grounds. Harry Seidler, no stranger to the courts, once remarked that he was tired of having to prove his houses innocent.

INTERNATIONAL STYLE VS ORGANIC ARCHITECTURE

In Sydney in 1950 Harry Seidler, who had trained at Harvard Graduate School under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, had completed his modernist masterpiece in the International Style: the Rose Seidler House. Ancher’s interpretation of International Style was tempered to a degree to suit local conditions and tastes; the Rose Seidler House, in contrast, was in absolute adherence to its principles – so much so that the house has been described by architectural writer Elizabeth Farrelly as ‘built manifesto’.

While Ancher and Seidler were exponents of the International Style, there was another mood afoot in architecture which drew its inspiration from the work of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), whose Fallingwater (1935) is one of the world’s most famous domestic buildings. Certain core principles carried throughout Wright’s long career. The relationship of the building to its site was of paramount importance and his houses tended to be low, horizontal structures in natural materials – wood, stone, timber and concrete – which were left unadorned. The influence of his Usonian houses, designed from 1936, can be seen in the work of Peter Muller, Neville Gruzman and Bruce Rickard, the latter commenting on the houses’ ‘scale, the use of space, the warmth and mellow look from natural materials’. These architects, in particular, identified strongly with Wrightian principles, which they adopted freely and adapted to suit their own aesthetic, the needs of the client and the site. Each house was seen as an individual exercise, whereas the International Style aimed for a superlative design that could provide a solution to any site, anywhere.

In his book Australia’s Home, Robin Boyd compares these two schools of thought and practice, and expresses with clarity what they hold in common.

‘However, the two schools shared many more fundamental precepts. In breaking with the popular stylistic conventions of the day, both believed that they were restoring the dignity of architecture. Both believed simplicity to be the omnipotent law of all design. Both rejected the idea of composing the façades of a building to preconceived rules. Both accepted spatial composition as the expressive field of architecture. Both believed that the building’s function was the only basis for planning and that it should (and would automatically if permitted) be expressed in the building’s form. Both believed that no material should be twisted into unnatural forms or asked to perform an unsuitable task.’

Despite these philosophical similarities, the resulting buildings could not have been more different. Seidler pulled no punches. ‘Does not this [organic] architecture seem rather weak, subservient and not very proud of itself?’ he said. Battle lines were drawn, particularly in Sydney, with architects such as Neville Gruzman rising repeatedly to the debate.

In a recent e-mail exchange with Peter Muller, I asked him if he was aware of Seidler’s quote at the time. Although he did not recall it, it didn’t surprise him, and he clarified his view on the matter. ‘Seidler was pushing for International architecture which abnegated all concerns to preserve local diversity. The climatic, the geographic, cultural and spiritual integrity, and deeper meanings for ornament were regarded as some kind of superstition. So-called organic architecture was regarded as “romantic” and intuitive, rather than intelligent and no match for what the Brave New World had to offer with its high-tech, machine-driven materials. Today, of course, with concerns for global warming, fossil fuels and so on, emphasis shifts once again and the use of natural and sustainable materials in an intelligent and sensible way to reduce energy overloads is considered admirable and strong minded. Pride comes before a fall, subservience to Truth is a blessing and the weak shall inherit the earth.’

Beginning in the early Fifties there was a developing movement in Sydney (a collection of individual architects but sometimes called a ‘school’ because of like-minded attributes) towards houses that embraced the Wrightian principles. These were often built on steep, difficult-to-access sites which were, as a result, relatively cheap to buy. They were located predominantly in bushland settings on Sydney’s North Shore, often battleaxe blocks not visible from the street. In An Australian Identity: Houses for Sydney 1953–63, Jennifer Taylor makes the point that there was a conscious ‘denial of pretentious display’ and an ‘intentional understatement’. The relationship to the land was central and the desire to integrate the building with the site with as little disruption as possible was the architect’s goal. In 1955, Peter Muller built a house for himself at Whale Beach which accommodated the existing trees and rocks, and his palette of building materials reflected the colours of the landscape, blending one with the other.

Muller claimed he was ‘not much of a functionalist…a plan that just works isn’t architecture’. These were often the homes of creative people – writers, artists, potters and architects themselves. In an era where the English country garden was still popular, it was considered somewhat ‘alternative’ to appreciate the native plants and bushland settings. The house Russell Jack designed on the upper North Shore for artist Tony Tuckson and his wife, Margaret, is invisible from the street and entirely open on one side to the bushland. Margaret Tuckson has lived there for nearly 50 years surrounded by art and ceramics.

Taking the bush setting to the ultimate of integration is the Glass House by Ruth and Bill Lucas, in Sydney’s Castlecrag. Designed in 1957, this glass pavilion illustrates the idea of ‘barely there’ structures and shows how Bill Lucas felt the frame was of crucial importance and ‘everything that goes on after that destroys the original structure’. Built for his family, and constructed with economy in mind, the house utilises standardised sections of steel, timber and glass.

OUTSIDE INFLUENCES

Travel was crucial for this generation of architects. Often their architectural degrees were practical in nature, covering carpentry, building techniques, engineering and classical architecture, but with little emphasis on contemporary buildings and current ideas. Exposure to other cultures and significant buildings in Europe and the United States was enormously influential. As, indeed, were the architectural journals of the day. George Henderson, who worked for ‘regional modernists’ Hayes and Scott, in Brisbane, and later for Seidler, recalls the subscriber copies of international magazines coming into the office. Pages were torn out and filed under the various architects of interest: Alvar Aalto, Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, Charles Eames, Mies van der Rohe and so on, each with their own file to be pored over and absorbed. Also significant was the role of émigrés as teachers and architects. Hayes and Scott. for example, were influenced by Dr Karl Langer, from Vienna, whose 1944 booklet, Sub-tropical Housing, advocated, amongst other things, long, shallow floor plans which allowed maximum penetration of natural light. Langer also developed the first sun chart for Brisbane, a copy of which every architectural practice had, and which was continually used at Hayes and Scott in their quest for optimum orientation.

Ken Woolley’s Mosman House (1962), looking towards the dining area on the top level and the living area on the lower level – all unified under one sloping roof line.

‘I JOINED THE NSW GOVERNMENT ARCHITECT’S OFFICE AS A STUDENT TRAINEE ON A SCHOLARSHIP AT THE AGE OF 16.

Harry Rembert, the Assistant Government Architect, was my mentor and a good designer himself. He took great pleasure in creating a design studio, which hadn’t existed before. The Public Works Department had been rather dormant, but accelerated during my time there. When I started, there were six people in the studio, and by the time I left in 1964 there were 25.

In 1958, Michael Dysart and I entered the Taubman’s Family Home Competition through the Women’s Weekly. We won £2000, which was quite a large sum then. The calls started coming in from people who wanted a house design – something cheap – and this started me thinking about the whole process of economy. We were asked to design houses for exhibitions – first for Cherrybrook Estate, and then in 1961 we were approached to design three houses for the Lend Lease Carlingford exhibition. Essentially these were exhibitions of architect-designed houses, with all the well-known names there. Lend Lease and Sunline Homes were the two players in the project homes market, and then Sunline Homes collapsed financially. Out of the collapse came Brian Pettit and Ron Sevitt’s partnership. Pettit & Sevitt differentiated itself by being absolutely modern with no compromise towards the more conservative mindset. By 1963, they were selling upwards of 200 houses per year.

Ken Woolley’s drawing of the celebrated Mosman House.

The launch of Pettit & Sevitt was concurrent with the design of my own house, the Mosman House, which explored my strong attraction to directness of detail and natural materials without artifice. I believe in building in a pragmatic way where the architecture is a result of making selections, judgements and choices. If you are sensible, you see the potential outcome of those choices as higher than the components. Then you have the chance of achieving something artistic. You have earned the right to be an artist because the practicalities have been covered.’

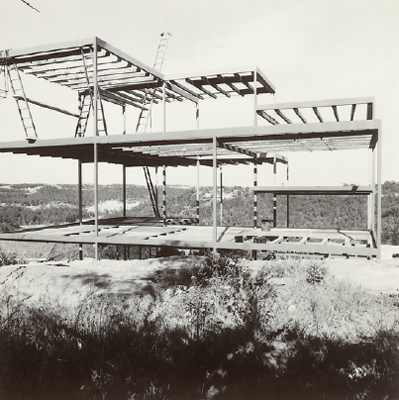

From left: Photographs taken during the construction of the Fombertaux House (completed 1966) in Sydney’s Lindfield East, show the precarious nature of the frame construction. While the house has a precision exterior, the interior allowed nature to intrude: a large rock forms part of the wall in the study.

Architects themselves brought a European sensibility to Australia. 1957, for instance, was the year that Danish architect Jørn Utzon’s design for the Sydney Opera House was picked, the story goes, from a pile of rejected entries by the great American architect Eero Saarinen, who missed the early stages of the judging. Amongst local architects, Seidler’s philosophy was shaped by the direct teachings of Gropius and Breuer; Taglietti came from postwar Italy where he was taught by Carlo Mollino and Pier Luigi Nervi; Iwanoff came from Bulgaria, and Buhrich from Germany via Holland and London. The influence of these architects on the local architectural landscape varies depending on their ability to practise. Seidler had no difficulties registering with the Board of Architects, perhaps because his qualifications were from the USA. Taglietti was permitted to practise through the Department of the Interior in Canberra, but both Iwanoff and Buhrich had a long battle with the Board before they were allowed to register and this had a limiting effect on their careers.

Architects who did travel were often able to find an inspirational source that resonated strongly with their natural inclination. For Bruce Rickard, who went to the USA in the Fifties, it was Wright’s Usonian houses, while for Neville Gruzman, some of whose houses were inspired by Wright, the major influence was Japanese architecture. He was not alone. Le Corbusier and Gropius had already earmarked the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto as praiseworthy for its use of modular space, simplicity and absence of extraneous detailing. Many attributes of Japanese architecture have been adopted for use in Australian domestic architecture: the tradition for post and beam construction; extensive use of wood and the exposure of the structural elements; sliding screens for flexible floor plans; changes in internal levels; framed garden views and the linking of internal and external space. Throughout this book the influence of Japanese architecture can be seen, particularly in the work of Gruzman, Boyd, Jack, McGlashan and Everist and McKay.

This architectural office (1958) of Robertson & Hindmarsh was built on the land of the family house in Sydney’s Seaforth. (When the office moved it became a hangout for the teenage children.) Copper panels clad an oregon frame, and the glass wall faced the view over the water. While it made a dramatic architectural statement in closeup, from a distance it melded into the surrounding bushland.

The houses shown in this book illustrate the diversity that occurred during the late Sixties and early Seventies. In Perth, Iwanoff had made concrete block his material of choice and his decorative façades became his signature. External patterning was matched by elaborate internal room dividers and bar areas with sculptural cutaway shapes. In Sydney both Collins and Buhrich were influenced by boat building in fibreglass. Collins constructed a whole house in the material while Buhrich’s fire-engine red moulded fibreglass bathroom is a high-design statement in a house with no shortage of individual ideas. Kenny, in Melbourne, had an early training under Kevin Borland, a socialist thinker, and his house was designed in modules in the hope that the concept would be adopted by a forward-thinking project home manufacturer. Unfortunately, that was not to be.

McKay’s holiday house for photographer David Moore is, on the other hand, a oneoff. Spare, utilitarian, and integrated into its rocky site, it is a design that is so site-specific it could never be repeated.

Stan Symonds’ house for John and Margaret Schuchard (1963) in Sydney’s Seaforth is possibly the best known work of this architect for whom the term ‘organic futurist’ is a fitting description.

‘THERE IS AN INCIDENT THAT I ALMOST FEEL DEFINES MY CAREER. I WAS AT A DRINKS PARTY AND A FELLOW ARCHITECT CAME UP AND INTRODUCED HIMSELF.

“I am Harry Howard. Who are you?” he asked. I said that I was Stan Symonds. “Don’t give me that bullshit, we all know that Stan Symonds is a name made up by a group of architects who want to do way-out work and not be identified.”

My work was acknowledged early on in my career with The Australian Journal of Architecture and Arts devoting a single issue to my projects in 1963. It included already built houses with proposals for apartment blocks. By that time, I had completed the Walsh House at Sackville on the flood-prone Hawkesbury River (1959), and an appreciation was growing for my shell-concrete work. The Jobson House at Bayview (1960), dubbed “The Egg and I” by the neighbours, was designed for Carl Jobson and his wife, Irene, who was a sculptor and potter and appreciated the form of the house. The Schuchard House (1963) at Seaforth was something of an owner-builder project. You see, concrete was as cheap as chips and form work wasn’t expensive. Concrete is my material of choice because of its plasticity. You can mould it to any shape, precast it, cast it on site, hand mix or machine mix. The result is highly sculptural architecture. My houses are very much site-specific. I spend time wandering around experiencing the site, the context, the view.

The design is the combination of first thoughts and the experience of being there. It has to look like it belongs. I have always worked that way and continue to do so.’

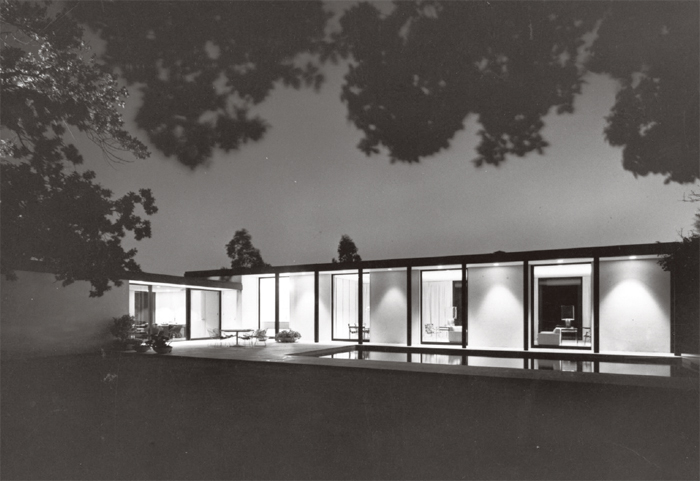

The Seccull House (1972) in Melbourne’s Brighton was one of Guilford Bell’s most satisfying houses. The relationship with the client was so good that the project became a wonderful example of Bell’s restrained and elegant approach to domestic architecture.

THE LEGACY

From the Fifties onwards, the kitchen slowly infiltrated the dining and living space – perhaps echoing women’s literal and metaphorical move from the confines of the walled-in kitchen. The kitchens themselves, often surprisingly small, modest yet ingeniously fitted out, were tucked behind partial walls or banks of storage cabinets, as in the Buhrich House. The open-plan kitchen/living/dining room (with direct access to a courtyard or ‘outdoor room’) that every house renovation aspires to today can find its antecedents in the relaxing of divisions, and the linking of spaces, pioneered by the forward-thinking architects featured on these pages.

Few of the architects (except perhaps Neville Gruzman and Guilford Bell, who both had a penchant for the glamorous effect of multiple mirrors) prefigured the rise of the bathroom as such an important room, or rooms, in the house. Of all the houses I visited, Buhrich’s red bathroom is a stand-out concept, and Kenny’s sliding doors onto a courtyard give an added dimension. The rest are small, functional places to wash and go.

What has altered drastically is the scale of homes. While the postwar restriction of 134 m2 was undeniably small, the average new house is now 264 m2 with 600 m2 not unheard-of. In some cases, with children leaving home later, they have to house two generations of adults, accommodate areas of privacy and provide space for the enormous amount of material goods we all acquire. Designwise, few domestic buildings, in this present look-at-me culture, share the Sydney School’s desire for modesty and lack of pretension. As Neil Clerehan pointed out, ‘We never imagined there would be a trend for Neo-Historicism. We thought we were forging a brand new way forward.’ Indeed, while visiting Russell Jack in Sydney’s Wahroonga, I parked opposite his rather hard-to-locate house, beside two enormous house developments, complete with columns and portico, pitched roofs and small windows.

This steel-framed house by Glenn Murcutt in Sydney’s Terrey Hills (1972–73) is a Miesian boxlike structure in its bushland setting. Murcutt visited the site after a bushfire, when blackened trees formed the landscape, and subsequently chose to clad the house’s exterior in black tiles. The house shows the beginnings of Murcutt’s interest in connecting the house with its setting.

There is much to be learnt from looking back and, hopefully, the examples contained in this book, and many others like them, will be around to inspire and inform new generations of architects. Sadly, as Professor Philip Goad pointed out, many of the light-structured Fifties buildings on valuable sites have already been demolished.

I came across this quote in Untold Stories by Alan Bennett, describing the demolition of his alma mater, Leeds Modern School. It reminds him of what Brendan Gill, a writer for The New Yorker, called the ‘Gordon Curve’ after architect Douglas Gordon of Baltimore.

‘This posits that building is at its maximum moment of approbation when it is brand new, that it goes steadily downhill and at 70 reaches its nadir. If you can get a building past that sticky moment, then the curve begins to go up again very rapidly until at 100 it is back where it was in year one. A 100-year-old building is much more likely to be saved than a 70-year-old one.’

Many of these houses are in middleage and have a long way to go to three score and ten. Let’s hope, with the help of sympathetic owners and bodies such as the Historic Houses Trust, Docomomo and the Robin Boyd Foundation, they make it to their centenary.

Set amongst the bushland of a conservative northern Sydney suburb is the house architect Harry Seidler designed for his parents. A passionate exponent of the International Style, Seidler exploited the principles he had learnt training under architectural greats Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer.