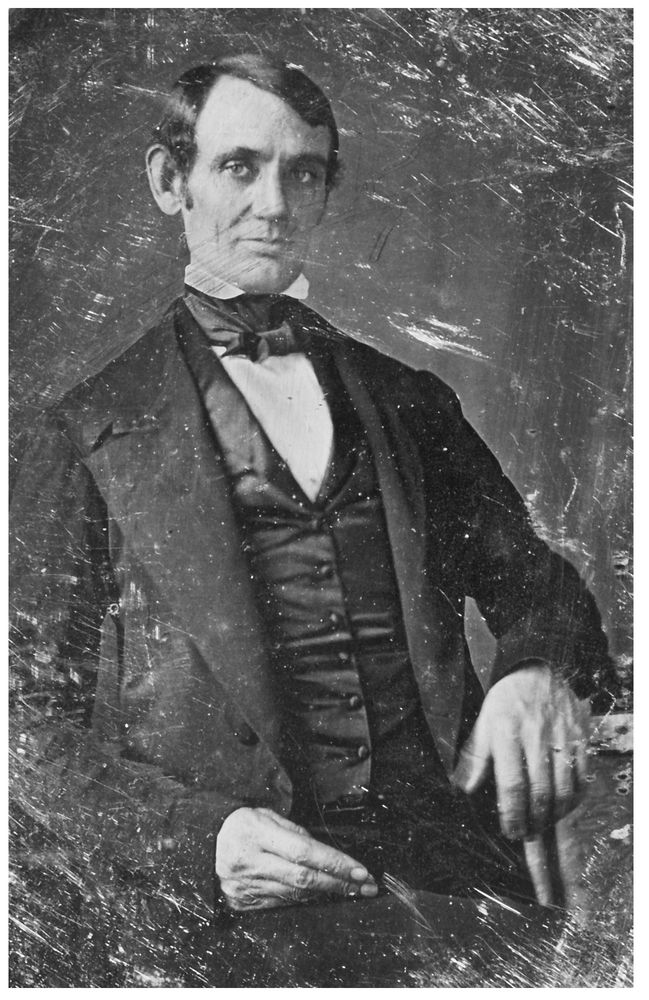

The earliest known photo of Lincoln, probably taken in Springfield,

Illinois, by Nicholas H. Shepherd (1846). Library of Congress

1

THE FACES OF LINCOLN

KARL WEBER

Karl Weber is a writer and editor based in Irvington, New York, who specializes in politics, public affairs, and business. He has coauthored such books as Creating a World Without Poverty, with Nobel Peace Prize–winner Muhammad Yunus, Demand: Creating What People Love Before They Know They Want It, with Adrian J. Slywotzky, and Citizen You: How Social Entrepreneurs Are Changing the World, with Jonathan M. Tisch. He edited the Participant Media Guides Food, Inc. and Waiting for “Superman.”

A mong the many unique distinctions borne by the sixteenth president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln is the first major historical figure to be known to us through photography. Every previous giant of history, from Nebuchadnezzar to Cleopatra, Charlemagne to Elizabeth I, has an image that is more or less vague, based purely on contemporary descriptions and depictions of doubtful accuracy. By contrast, we know Lincoln the same way we later came to know Churchill and Hitler, Elvis and Marilyn, Ali and Oprah—through photographs that capture the concrete reality of the human face with a vividness, nearness, and objectivity previously impossible.

What’s more, as with those later representatives of twentieth-century celebrity culture, we know Lincoln through a series of specific, iconic photos—images that somehow capture not just the reality of a moment in time but the historic context within which a life took shape and meaning. Close your eyes and the familiar images of Lincoln flash by on a mental screen: The senate candidate, young and beardless, with rumpled collar, a gently lopsided smile, and an untamable shock of hair slightly askew. The president on the battlefield at Antietam, impressively lean, towering in his stovepipe hat over his officers. The father, seated in an armchair, casting a gentle, bespectacled glance at an album spread open on his lap for the benefit of young Tad standing at his side. The aging statesman, his visage deeply care-creased, his eyes sunken as if haunted by the carnage of war, just days away from his own death (as we know, though he does not).

The faces of Lincoln, which we know through the mystery of photography; fragments of unmediated reality that are unmistakably alive yet somehow distant and untouchable, like the man himself.

About 130 authenticated Lincoln photos are now known. (You’ll find reproductions of a number of them scattered through the pages of this book.) From those photographic images evolve the other familiar faces of Lincoln—the many Lincolns that pop up in people’s minds when the name is mentioned: the portraits on the penny and the five-dollar bill, the disembodied granite head on Mount Rushmore, the nineteen-foot-tall figure of Georgia white marble grandly enthroned in Washington, and the filmed embodiments by actors from Walter Huston and Raymond Massey to Henry Fonda, Gregory Peck, and Sam Waterston—and now, of course, Daniel Day-Lewis in the new film, scripted by Tony Kushner and directed by Steven Spielberg, that is the occasion for the publication of this book. And let’s not exclude such pop-culture incarnations as the audioanimatronic figure stiffly reciting excerpts from Lincoln speeches to entertain tourists at Disney World or the bearded, semi-comic pitchmen in a hundred television commercials promoting Presidents’ Day auto sales. These, too, are faces of Lincoln—low-brow tributes to the national obsession with our greatest president and arguably our single greatest historical figure.

Every American president has multiple meanings—that’s in the nature of politics and history, particularly in a country as vast, diverse, and eternally contentious as ours. But the amazing multiplicity of Lincolns is unique among presidents. Scholar Merrill D. Peterson has boiled them down to five core archetypes: Savior of the Union, Great Emancipator, Man of the People, First American, and Self-Made Man.

1 From these five, as Peterson amply documents, flow countless variants.

Some of these multifarious Lincoln images were current in his own day and were fodder for his political campaigns, as well as his opponents’. Sobriquets like the Railsplitter, Woodchopper of the West, and Honest Abe were concocted as slogans; so were insults like the Black Republican and the Illinois Baboon, often accompanied by cartoons depicting Lincoln not just as ugly, buffoonish, and dimwitted but as harboring a secret lust for Negro women. (Images like these are worth recalling when the media declares the latest presidential race “the dirtiest ever”—as they do like clockwork, every four years.)

Other Lincolns have proliferated in the public consciousness during the century and a half since his death. Many have solid grounding in historical fact, others a mere toehold. Most of us have at least a passing acquaintance with many of these Lincolns from a school history class or a Ken Burns documentary.

There’s Lincoln the frontiersman, the enterprising but largely unsuccessful businessman, the comic-opera warrior (leader of a tiny company of Illinois militia that served—and saw no combat whatsoever—during the short-lived Black Hawk War of 1832), and the aspiring inventor. (Lincoln remains the only president ever to have obtained a US patent, although the gadget he designed for lifting boats over shoals in riverbeds was never manufactured.)

There’s Lincoln the shrewd self-taught attorney, the cracker barrel philosopher, and the indefatigable teller of stories, some downright obscene. (During his own lifetime, books purporting to collect Lincoln’s favorite jokes and anecdotes—edited to suit Victorian notions of propriety—were already in circulation. No high school history book is likely to ever include Lincoln’s scandalous but hilarious story about Ethan Allen and the outhouse—though it appears, remarkably, in Kushner’s screenplay for Spielberg’s Lincoln.)

There’s Lincoln the family man, the (supposedly) henpecked husband, the doting father who let his small son run wild through the White House, the brooding sufferer from depression, and (some say) the “first gay president.” (More on that notion later.)

There’s Lincoln the Byronic lifelong aspirant to power, whose ambition (according to his longtime law partner William Herndon) “was an engine that knew no rest,” the debater and orator of unmatched wit and eloquence, the obsessively self-editing speechmaker and letter writer, and the master of public opinion and political timing.

And of course there is Lincoln the lifelong opponent of slavery, the single-minded Union man, the ruthless wielder of military power, the tenderhearted commuter of sentences, the grieving father of his people, the Great Emancipator, and, ultimately, the martyr and savior of the nation.

So many Lincolns, each one somebody’s favorite—especially, perhaps, the Lincolns of myth and legend. For the incurable romantic, the Lincoln of choice may be the grief-stricken frontier lover at the grave of Ann Rutledge, reputedly the one true passion of his life. (The image derives from an old, unsubstantiated story popularized by Herndon, who never much liked Mary Lincoln, and by Carl Sandburg, Lincoln’s sentimental, quasi-official historian for much of the twentieth century.) For the autodidact, there’s Lincoln riding the rural legal circuit, his nag of a horse dwarfed by its giant rider and walking at a snail’s pace as Lincoln neglects the spurs, eagerly devouring yet another volume of Blackstone’s Commentaries. For the believer in genius through inspiration, there’s the president hastily penning his immortal speech on a fragment of torn cardboard while riding the train to Gettysburg (another myth too good to be abandoned despite the evidence against it).

Of course, I have my favorite Lincolns, too. As a lifelong baseball fan, I have a soft spot for an old story that says that Lincoln was in the middle of a game when a delegation arrived in Springfield from the Republican National Convention to formally notify him that he’d been nominated for the presidency. According to legend, Lincoln demurred, “Tell the gentlemen they will have to wait a few minutes until I get my next turn at bat.”

Did it really happen? It’s certainly possible, but only in the sense that it’s possible I myself might be nominated for the presidency by the next Republican convention. The Mills Commission, the baseball history committee that came up with this story in 1939, is the same group that declared Abner Doubleday the inventor of the sport, a finding that every serious historian considers a mere fairy tale. But we baseball aficionados cling to it because it validates the historical status of our favorite game by associating it with America’s greatest president.

I haven’t yet stumbled across any articles claiming that Lincoln was an avid golfer, but I don’t doubt they exist.

aAs George Orwell said about Charles Dickens, Lincoln is well worth stealing—so it’s no wonder that practically everybody has tried to appropriate him in support of their particular cause. Advocates of civil rights and racial equality, of course, have always recognized Lincoln as a spiritual ancestor. Not for nothing did Martin Luther King Jr. give his greatest address under Lincoln’s marble gaze. That hasn’t stopped white supremacists from cherry-picking Lincoln quotes to declare him a racist, a staunch advocate of segregation, and an opponent of racial equality.

In similar fashion, Lincoln (who was in fact a teetotaler in life) has been claimed by antiliquor crusaders as a “dry” and by the opposition as a “wet.” During the debate over prohibition, while temperance crusaders were quoting Lincoln’s comments about the evils of drink, publicists for a liquor industry association had copies of a liquor license granted to Lincoln during his youthful days as a storekeeper printed and distributed for proud display on the walls of taverns around the country.

Lincoln has been cited as a pioneering anti-imperialist (based on his vocal opposition to the Mexican War) and enlisted as a jingoist advocate of America’s Manifest Destiny to expand. As Christopher A. Thomas has explained, the Lincoln Memorial itself was designed and built as part of a program by Republican Party leaders to celebrate the “active presidency” they credited Lincoln with establishing and that they saw embodied in such later enterprises as the Spanish-American War and the global American empire it spawned.

Lincoln has been hailed as both a laissez-faire free marketer and a defender of the downtrodden working man. During the 1930s, financiers named savings banks and insurance companies after Lincoln even as the American Communist Party was staging “Lincoln-Lenin” marches in honor of his proletarian sympathies. And Lincoln’s Prophecy, a bogus screed warning against capitalist tyranny and the enthronement of corporate power in America, still circulates over Lincoln’s signature, more than a century after it was first forged for use in the 1896 presidential campaign—now appropriated, inevitably, in support of the Occupy movement.

Liberal New York governor Mario Cuomo has enlisted the spirit of Lincoln on behalf of a twenty-first-century campaign against poverty, while conservative columnist George Will has called him a forebear of the antiabortion movement. Lincoln has been depicted as a prototype of the management consultant, an erstwhile leadership coach, a glad-handing self-help guru in the mold of Dale Carnegie, and most recently (heaven help us) as a vampire hunter.

And of course the multifarious Lincoln legend has long transcended national boundaries. The Russian novelist and spiritual seeker Leo Tolstoy (who called Lincoln “a Christ in miniature”) told of meeting a Muslim chieftain in the remote Caucasus who affirmed that, yes, he had heard of the great American Lincoln: “He was a hero. He spoke with a voice of thunder; he laughed like the sunrise and his deeds were as strong as the rock and as sweet as the fragrance of rose.” Passed from place to place and from person to person, Lincoln’s story had become transmuted into a larger-than-life tale from mythology. Years later, India’s Jawaharlal Nehru kept two inspirational sculptures on his office desk—a statuette of Gandhi and a bronze cast of Lincoln’s hand. The Republic of China issued postage stamps pairing Lincoln with Sun Yat-Sen, while Ghana issued a set of three depicting its prime minister Kwame Nkrumah paying homage at the Lincoln Memorial.

So many Lincolns—and who is to say that any of them is definitely wrong?

Even those who knew Lincoln personally confessed—often with bafflement—his many-sidedness and the essential elusiveness of his character. Frederick Douglass, the greatest African American leader of the nineteenth century, met with Lincoln on several occasions and was referred to by the president as “my friend Douglass.” He visited Lincoln at the White House (sometimes having to argue with racist guards before gaining admittance), famously lauded the second inaugural address as “a sacred effort” and in his memoirs declared, “Mr. Lincoln was not only a great president, but a great man—too great to be small in anything. In his company I was never in any way reminded of my humble origin, or of my unpopular color.” Yet in his 1876 speech at the unveiling of the Freedmen’s Monument to Lincoln in Washington, Douglass also called him “preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men,” avowed that Lincoln “shared the prejudices common to his countrymen towards the colored race,” and summed up Lincoln’s antislavery efforts this way: “Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent ; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.” The description is paradoxical, as if, for Douglass, Lincoln’s heroism, although undeniable, is festooned with caveats and limitations. (In his essay in this book, scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. offers a much more detailed analysis of Lincoln’s mixed meaning for Douglass and, indeed, for many African Americans.)

Some later interpreters of Lincoln have painted similarly mixed portraits. The great filmmaker D. W. Griffith somehow managed to treat Lincoln as a hero of unmatched nobility in the same film, Birth of a Nation , that depicted the terror-wielding Ku Klux Klan as representatives of Southern heroism, and, in his best-selling historical novel Lincoln, Gore Vidal portrayed him as a masterful politician, a would-be tyrant, and a calculating, devious egotist who even infected his family with syphilis.

Most Americans have a less ambivalent attitude toward Lincoln. Yet our emotional and intellectual ties to Lincoln tend to be far more complicated and far more personal than our links to most other historical personages. Only Lincoln could have inspired perhaps the greatest and most psychologically intimate elegy ever written about a public figure. Walt Whitman had never met Lincoln, though he often glimpsed him in the streets of Washington during the war years when Whitman worked as a nurse tending wounded soldiers. Yet Whitman’s elegy reads like a tribute from a lover to his beloved:

When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d,

And the great star early droop’d in the western sky in the night,

I mourn’d, and yet shall mourn with ever-returning spring.

Ever-returning spring, trinity sure to me you bring,

Lilac blooming perennial and drooping star in the west,

And thought of him I love. . . .

O how shall I warble myself for the dead one there I loved?

And how shall I deck my song for the large sweet soul that has gone?

And what shall my perfume be for the grave of him I love?

Sea-winds blown from east and west,

Blown from the Eastern sea and blown from the Western sea,

till there on the prairies meeting,

These and with these and the breath of my chant,

I’ll perfume the grave of him I love.

In his essay “Fern-Seed and Elephants,” the literary critic, novelist, and Christian apologist C. S. Lewis contrasts the ways we relate to historical figures and literary characters:

There are characters whom we know to be historical but of whom we do not feel that we have any personal knowledge—knowledge by acquaintance; such are Alexander, Attila, or William of Orange. There are others who make no claim to historical reality but whom, none the less, we know as we know real people: Falstaff, Uncle Toby, Mr. Pickwick. But there are only three characters who, claiming the first sort of reality, also actually have the second. And surely everyone knows who they are: Plato’s Socrates, the Jesus of the Gospels, and Boswell’s Johnson. . . . We are not in the least perturbed by the contrasts within each character: the union in Socrates of silly and scabrous titters about Greek pederasty with the highest mystical fervor and the homeliest good sense; in Johnson, of profound gravity and melancholy with that love of fun and nonsense which Boswell never understood though Fanny Burney did; in Jesus of peasant shrewdness, intolerable severity, and irresistible tenderness.

Of course, Lewis’s list of complex, vibrantly living historical personages—Socrates, Jesus, and Johnson—is the list that a scholarly, Christian Englishman would propose. For Americans, Lincoln is the undeniable fourth. The more we learn about Lincoln, and in particular the more we read Lincoln’s own writings—the great speeches, the transcripts of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, the letters and notes he drafted in response to personal queries and political controversies—the more deeply we feel the reality of his complicated and endlessly fascinating personality. Arch-cynic H. L. Mencken complained (in his third book of Prejudices, 1922) that “the varnishers and veneerers have been busily converting Abe into a plaster saint, thus making him fit for adoration in the Y.M.C.A.’s. . . . Worse, there is an obvious effort to pump all his human weaknesses out of him, and so leave him a mere moral apparition, a sort of amalgam of John Wesley and the Holy Ghost.” Maybe so—but when it comes to Lincoln, the work of the varnishers and veneerers has been largely futile. Unlike George Washington, who is for most Americans a plaster saint, we feel we know Lincoln as we know a friend or a family member; we understand, accept, and even revel in the contrasts in his character.

Lincoln somehow belongs to each of us, with a special intimacy that marks our relationship to few other public figures—especially when we limit ourselves to public figures from before today’s era of factitious hy-perintimacy. Fueled by the Internet and by media phenomena ranging from People magazine and reality TV to continually streaming Twitter feeds, millions of ordinary citizens now apparently think of actors, athletes, and, yes, politicians as if they are close personal friends. It’s an illusion, of course, but one that publicists, producers, and marketers are eager to feed and exploit. Lincoln is one of the few historical figures from the nineteenth century or earlier whom it’s possible to imagine in this context, as Harold Holzer artfully explains in his essay in this book, “Lincoln—The Unlikely Celebrity.”

And yet, despite the sense of intimacy we feel toward Lincoln (enhanced by the endless stream of biographies, histories, picture books, television shows, movies, and other bits of Lincolniana produced every year), it remains startlingly difficult to pigeonhole, dismiss, ignore, or patronize him. Lincoln still towers above us and our history, and the more we know about him the greater he seems to loom.

In this, our relationship to Lincoln mirrors that of his contemporaries. In Washington’s lifetime, no one ever underestimated him; his physical stature, personal beauty, unblemished rectitude, and austere presence caused those around him to regard him with admiration bordering on awe. (On a bet, Gouverneur Morris once famously dared to greet Washington with a slap on the back; the blood-chilling glare he received in response made Morris vow never to repeat the gesture.)

By contrast, everyone underestimated Lincoln. Contemporary testimony makes it clear that most of the famous “team of rivals” who ended up as members of Lincoln’s cabinet were initially baffled to find themselves politically outmaneuvered by someone they considered an uneducated frontiersman. But, the more they got to know him, the greater the depths of insight and wisdom they saw in him (one of the many nuances of the Lincoln story that is subtly and effectively captured in Tony Kushner’s screenplay). By the time of his death, most had come to recognize in Lincoln a man of overpowering stature—not just politically but intellectually, spiritually, and morally.

Many have used the word “Shakespearean” to describe Lincoln and his story. It’s apt in several senses. Lincoln himself loved the works of Shakespeare (especially Macbeth) and infused his own writings with Shakespearean echoes. More important, Shakespeare is the supreme literary depicter of genius. It’s notoriously difficult for a writer to portray, in a novel or drama, a character who is more brilliant, more complex, or simply bigger than himself—but Shakespeare has done it. When we read Hamlet or Lear, Henry IV or Othello, we actually feel and believe that we are in the presence of personal greatness. And when we read Lincoln’s life or his writings, we feel the same way.

Partly this is due to the circumstances of his life and death—the preeminent role he played, after being launched from obscurity, in the central drama of his day, which is still, a century and a half later, the central drama of American history. As many have noted, the Civil War is to the people of the United States what the Trojan War was to the ancient Greeks—the fount of our mythology, our literature, our complicated self-image, our enduring conflicts. The story of that war—its origin in the great national sin of slavery, its inexorable outbreak despite the efforts of generations of statesmen to avoid it, its horrific unfolding through a litany of Homeric clashes and grinding carnage, its remarkable cast of secondary characters, its shocking conclusion (including the martyrdom of its greatest hero—on Good Friday, no less) and, finally, its tragic, still-unfolding legacy—this story feels too vast and too mythic to be true.

Yet it is true. And the frontier lawyer Lincoln somehow rose in stature not simply to be worthy of that grand stage but to dominate it—even while remaining the husband of the troubled, often querulous Mary (fussing over dressmaker’s bills), the shrewd politico (swapping postmasterships in little one-horse towns for the votes needed to free the slaves), the cackling teller of off-color stories, and all the rest. Somehow our Lincoln remains resolutely mortal and human while transcending mere mortality, mere humanity, as figures from mythology do.

The stature of Lincoln continues to amaze. He towers not only over his contemporaries but over us. And so, when we try to appropriate him to play a role in some modern controversy, we find (if we are honest) that he overwhelms us.

Take, for example, the issue of Lincoln’s sexuality. For generations, some have wondered whether Lincoln was purely heterosexual in his orientation. Writing in 1926 about Lincoln’s youthful friend Joshua Fry Speed, Sandburg described their friendship as having “a streak of lavender, and spots soft as May violets” (using common 1920s code for what we now call gay relations). In 1995, with the issues of gay rights and even same-sex marriage having battled their way into the political limelight, psychologist C. A. Tripp published a book that claimed Lincoln was fundamentally homosexual in orientation.

Most historians have dismissed Tripp’s claim, saying he misinterpreted such once-common practices as men sharing a bed while traveling. But for a time, the furor over Tripp’s book catapulted Lincoln once again to the center of the political stage. Emotions ran high. Conservative columnist (and gay rights advocate) Andrew Sullivan wrote an article in the

New Republic in which he declared,

The truth about Lincoln—his unusual sexuality, his comfort with male-male love and sex—is not a truth today’s Republican leaders want to hear. They are well-advised to attack and suppress it. They are more closely related to the forces Lincoln defeated than those he championed; and his candor, honesty, and brave forging of a homosocial and homoerotic life in plain sight would appall them. The real Lincoln is their greatest rebuke. Which is why they will do all they can to obscure the complicated, fascinating truth about the man whose legacy they are intent on betraying.

Sullivan’s assumptions about Lincoln’s erotic life may be questionable. But there’s no doubt that the relationship between Lincoln—one of the founders of the Republican Party—and the conservative religious leaders who are among the chief supporters of today’s Republican Party is an uneasy one. (Historian Richard Carwardine analyzes the issue in fascinating detail in his essay in this book “The Almighty Has His Own Purposes”: Abraham Lincoln and the Christian Right.) In that sense, Sullivan’s observation that Lincoln represents a “rebuke” to today’s political leaders is an understandable one.

But the rebuke that Lincoln represents goes far beyond his sexuality, as a careful reading of Lincoln’s greatest utterance, the second inaugural address, suggests.

Twenty-first century politicians, like their counterparts in Lincoln’s day, don’t hesitate to invoke religion when they find it convenient. Most citizens have learned to respond to such appeals with cynicism. That makes it especially stunning to discover, in the second inaugural address, the unmistakable voice of a politician who actually believes in God—who takes seriously the notion of divine justice and has wrestled in trembling and anguish with its implications for himself personally and for the nation he leads.

Everyone knows the fourth and final paragraph of the speech, which begins, “With malice toward none; with charity for all; . . . ” It’s a graceful, beautiful benediction. But its sweetness is deepened by the contrast with the two preceding paragraphs, which set forth a moral synopsis of the history and meaning of the Civil War.

It’s noteworthy that Lincoln refuses to posture or congratulate his (Northern) audience about the justice of the Union cause in that war (though surely Lincoln believed that if any cause was ever just, that one was). Instead, he tartly observes:

One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war.

That word “somehow” is a characteristically shrewd Lincoln touch. He meticulously refuses to be drawn into arguments about the precise relationship between slavery and the war. White Southerners would define that relationship one way; Northern abolitionists would define it another way; many others on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line would define it in still other ways. Lincoln will not be drawn into a fruitless debate about how to apportion the blame for the war—but he wants to insist that, “somehow,” it has been a war about slavery, because, as we will see, this is to be his central theme.

Lincoln presses on to describe how the Civil War, like many another war, has had unintended, far-reaching consequences:

Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict [i.e., slavery] might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding.

What

moral sense does Lincoln make of these facts—of the appalling length and destructiveness of the war? He spends the rest of the long third paragraph offering his interpretation, which is deeply rooted in biblical notions of justice, retribution, and the inevitable consequence of sin. He quotes Matthew 18:7: “Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” And from Lincoln’s unflinchingly honest contemplation of the meaning of this text for Americans emerges this syllogism:

If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him?

For a modern reader, steeped in twenty-first century styles of political discourse, it’s difficult at first to realize that Lincoln is saying exactly what he appears to be saying: “this terrible war” has been visited upon Americans because we deserve it. And, yes, “both North and South” deserve it, for both North and South countenanced the offence of “American Slavery.” Note that last phrase. Unlike most writers of textbook histories and modern politicians, Lincoln refuses to pretend that the crime of slavery was some sort of aberration, irrelevant to the true “character” of our people. No, he brands it as what it was: “American Slavery,” our nation’s uniquely tragic contribution to the register of historic evils.

Every schoolchild knows that the adjective “honest” is permanently affixed to Lincoln. That has been true since Lincoln’s own time; as we’ve noted, the phrase “Honest Abe” originated as a campaign slogan. But the moniker is too cute, suggesting a president we might even be able to patronize. It conjures up the legend of the teenaged store clerk who walked three miles to return six cents in change mistakenly left behind by a customer—honest almost to excess. That’s one kind of honesty, admirable in its own way.

But the really remarkable thing about Lincoln’s honesty is its

ruthlessness (akin to the “coldness” of which Herndon spoke). The Lincoln who speaks in this address is profoundly aware of the suffering of hundreds of thousands of mothers and fathers, wives and sweethearts, brothers and sisters who had lost loved ones to death, disease, or dismemberment in the war that Lincoln had insisted on prosecuting despite criticism from all sides, including some of his most fervent and moralistic supporters. He has spoken to many of those bereaved ones, held their hands, looked them in the eye. One need only reread Lincoln’s famous letter to Mrs. Bixby to recall the tender sympathy of which he was capable:

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle. I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save. I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.

Yet this same man has the honesty—and the temerity—to address Mrs. Bixby and her fellow mourners (along with the rest of the nation that re-elected him) and say, in effect, We deserve this war, and all the suffering it has brought.

This is honesty almost beyond human bearing: fierce, fiery, implacable.

Thankfully, although Lincoln finds this harsh conclusion unavoidable, he refuses to take any pleasure in it. (In that, he is unlike, for example, some preachers of Lincoln’s own time as well as today, who seem to relish the vision of apocalypse that sin is surely bringing to America.) Instead, Lincoln offers a plea that surely echoes the content of his private meditations in the White House: “Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.”

But he still won’t let us, his auditors and his fellow countrymen, off the hook:

Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

Most politicians of Lincoln’s era—and our own—who choose to speak about God do it purely to flatter themselves and their audience; to reassure their listeners that God is on their side. But Lincoln refuses to flatter himself or us. He respects us too much for that. Instead he models what may be the highest degree of spiritual maturity—the readiness to see and judge oneself through God’s eyes, with unflinching honesty, not wallowing in one’s sins (or those of one’s people) but acknowledging them as the first essential step toward repentance, reform, and reconciliation.

Andrew Sullivan was right—but I would go farther than Sullivan did. The “real Lincoln” is the “greatest rebuke”—but not just for Republicans or Democrats, conservatives or liberals, Northerners or Southerners, but for all of us.

Lincoln is us—the “First American,” in Merrill D. Peterson’s words. But he is us at the peak of our greatness, continually reminding us of how far we fall short and urging us on to the heights of integrity and honesty, compassion and mutual forgiveness that he knows we are capable of achieving. This, for me, is the deepest message we read when we gaze yet again upon that face we’ve found so mesmerizing for the past century and a half—the face of the greatest American, the face of our Abraham Lincoln.

LINCOLN’S WORDS

To the People of Sangamo County (1832)

Lincoln’s first political pronouncement

Fellow Citizens:

Having become a candidate for the honorable office of one of your representatives in the next General Assembly of this state, in accordance with an established custom, and the principles of true republicanism, it becomes my duty to make known to you—the people whom I propose to represent—my sentiments with regard to local affairs.

Time and experience have verified to a demonstration, the public utility of internal improvements. That the poorest and most thinly populated countries would be greatly benefitted by the opening of good roads, and in the clearing of navigable streams within their limits, is what no person will deny. But yet it is folly to undertake works of this or any other kind, without first knowing that we are able to finish them—as half finished work generally proves to be labor lost. There cannot justly be any objection to having rail roads and canals, any more than to other good things, provided they cost nothing. The only objection is to paying for them; and the objection to paying arises from the want of ability to pay.

With respect to the County of Sangamo, some more easy means of communication than we now possess, for the purpose of facilitating the task of exporting the surplus products of its fertile soil, and importing necessary articles from abroad, are indispensably necessary. A meeting has been held of the citizens of Jacksonville, and the adjacent country, for the purpose of deliberating and enquiring into the expediency of constructing a railroad from some eligible point on the Illinois river, through the town of Jacksonville, in Sangamo county. This is, indeed, a very desirable object. No other improvement that reason will justify us in hoping for, can equal in utility the rail road. It is a never failing source of communication, between places of business remotely situated from each other. Upon the rail road the regular progress of commercial intercourse is not interrupted by either high or low water, or freezing weather, which are the principal difficulties that render our future hopes of water communication precarious and uncertain. Yet, however desirable an object the construction of a rail road through our country may be; however high our imaginations may be heated at thoughts of it—there is always a heart appalling shock accompanying the account of its cost, which forces us to shrink from our pleasing anticipations. The probable cost of this contemplated rail road is estimated at $290,000;—the bare statement of which, in my opinion, is sufficient to justify the belief, that the improvement of the Sangamo river is an object much better suited to our infant resources.

Respecting this view, I think I may say, without the fear of being contradicted, that its navigation may be rendered completely practicable, as high as the mouth of the South Fork, or probably higher, to vessels of from 25 to 30 tons burthen, for at least one half of all common years, and to vessels of much greater burthen a part of that time. From my peculiar circumstances, it is probable that for the last twelve months I have given as particular attention to the stage of the water in this river as any other person in the country. In the month of March, 1831, in company of others, I commenced the building of a flat boat on the Sangamo, and finished and took her out in the course of the spring. Since that time, I have been concerned in the mill at New Salem. These circumstances are sufficient evidence, that I have not been very inattentive to the stages of the water.—The time at which we crossed the mill dam, being in the last days of April, the water was lower than it had been since the breaking of winter in February, or than it was for several weeks after. The principal difficulties we encountered in descending the river, were from the drifted timber, which obstructions all know is not difficult to be removed. Knowing almost precisely the height of water at that time, I believe I am safe in saying that it has often been higher as lower since.

From this view of the subject, it appears that my calculations with regard to the navigation of the Sangamo cannot be unfounded in reason; but whatever may be its natural advantages, certain it is, that it never can be practically useful to any great extent, without being greatly improved by art. The drifted timber, as I have before mentioned, is the most formidable barrier to this object. Of all parts of this river, none will require so much labor in proportion, to make it navigable, as the last thirty or thirty-five miles; and going with the meanderings of the channel, when we are this distance above its mouth, we are only between twelve and eighteen miles above Beardstown, in something near a straight direction; and this route is upon such low ground as to retain water in many places during the season, and in all parts such as to draw two-thirds or three-fourths of the river water at all high stages.

This route is upon prairie land the whole distance;—so that it appears to me, by removing the turf, a sufficient width and damming up the old channel, the whole river in a short time would wash its way through, thereby curtailing the distance, and increasing the velocity of the current very considerably, while there would be no timber upon the banks to obstruct its navigation in future; and being nearly straight, the timber which might float in at the head, would be apt to go clear through. There are also many places above this where the river, in its zig zag course, forms such complete peninsulas, as to be easier cut through at the necks than to remove the obstructions from the bends—which, if done, would also lessen the distance.

What the cost of this work would be, I am unable to say. It is probable, however, it would not be greater than is common to streams of the same length. Finally, I believe the improvement of the Sangamo river, to be vastly important and highly desirable to the people of this county; and if elected, any measure in the legislature having this for its object, which may appear judicious, will meet my approbation, and shall receive my support.

It appears that the practice of loaning money at exorbitant rates of interest, has already been opened as a field for discussion; so I suppose I may enter upon it without claiming the honor, or risking the danger, which may await its first explorer. It seems as though we are never to have an end to this baneful and corroding system, acting almost as prejudiced to the general interests of the community as a direct tax of several thousand dollars annually laid on each county, for the benefit of a few individuals only, unless there be a law made setting a limit to the rates of usury. A law for this purpose, I am of opinion, may be made without materially injuring any class of people. In cases of extreme necessity there could always be means found to cheat the law, while in all other cases it would have its intended effect. I would not favor the passage of a law upon this subject, which might be very easily evaded. Let it be such that the labor and difficulty of evading it, could only be justified in cases of the greatest necessity.

Upon the subject of education, not presuming to dictate any plan or system respecting it, I can only say that I view it as the most important subject which we as a people can be engaged in. That every man may receive at least, a moderate education, and thereby be enabled to read the histories of his own and other countries, by which he may duly appreciate the value of our free institutions, appears to be an object of vital importance, even on this account alone, to say nothing of the advantages and satisfaction to be derived from all being able to read the scriptures and other works, both of a religious and moral nature, for themselves. For my part, I desire to see the time when education, and by its means, morality, sobriety, enterprise and industry, shall become much more general than at present, and should be gratified to have it in my power to contribute something to the advancement of any measure which might have a tendency to accelerate the happy period.

With regard to existing laws, some alterations are thought to be necessary. Many respectable men have suggested that our estray laws—the law respecting the issuing of executions, the road law, and some others, are deficient in their present forms, and require alterations. But considering the great probability that the framers of those laws were wiser than myself, I should prefer [not?] meddling with them, unless they were first attacked by others, in which case I should feel it both a privilege and a duty to take that stand, which in my view, might tend most to the advancement of justice.

But, Fellow-Citizens, I shall conclude.—Considering the great degree of modesty which should always attend youth, it is probable I have already been more presuming than becomes me. However, upon the subjects of which I have treated, I have spoken as I thought. I may be wrong in regard to any or all of them; but holding it a sound maxim, that it is better to be only sometimes right, than at all times wrong, so soon as I discover my opinions to be erroneous, I shall be ready to renounce them.

Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem. How far I shall succeed in gratifying this ambition, is yet to be developed. I am young and unknown to many of you. I was born and have ever remained in the most humble walks of life. I have no wealthy or popular relations to recommend me. My case is thrown exclusively upon the independent voters of this county, and if elected they will have conferred a favor upon me, for which I shall be unremitting in my labors to compensate. But if the good people in their wisdom shall see fit to keep me in the back ground, I have been too familiar with disappointments to be very much chagrined.

Your friend and fellow-citizen,

A. Lincoln

New Salem, March 9, 1832.