An Edited Excerpt of My Presentation

Capitalism is an economic system characterized by commodity production and private appropriation, in which one section of people monopolizes the means of subsistence and production, and most people are forced to sell their labor to survive.

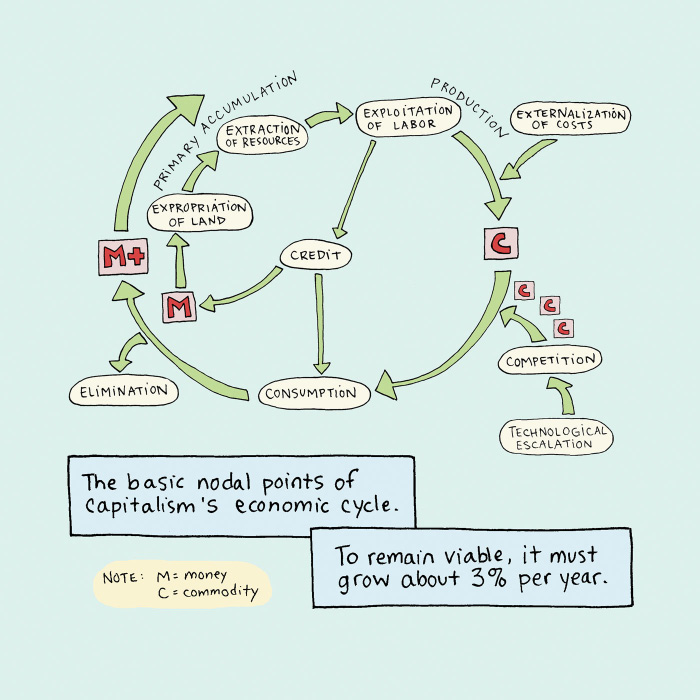

Capitalism is, on the one hand, a social relation, whereby one class dominates all others. On the other hand it’s a process—the endless flow of money to commodity production for the generation of more money.

But it’s not linear; it’s both cyclical and progressive, like a spiral.

The first part of the process is primary accumulation, where land is expropriated and resources are extracted. A bank or a queen or anyone who already has surplus wealth extends a line of credit to some explorer to gather a group of armed thugs, go out into the world, locate wealth, and steal it.

The expropriation of land does a few things. The conqueror can use that land and extract whatever is in and on it. And as the people are dispossessed—no longer able to live on the land—they’re forced into cities and become dependent on jobs. This is how the working class is created and continuously resupplied. It also creates the consumer: without land, we have to pay for food, shelter, and all our other needs.

The next part is production. One of the defining features of capitalist production is the exploitation of labor. Exploitation has a precise meaning in economics, which isn’t simply using someone for material gain.

It means the worker is paid less than the exchange value of what they produce. During the time that they’re paid $10, they might make items worth $100. That extra $90, minus fixed costs, is surplus value that the capitalist privately appropriates—in other words, steals.

Externalization of costs is another way the capitalist commits theft, and murder as well. Pollution from the production process is discharged into the environment. The numerous and serious consequences, never mind the cleanup which never happens, are not paid for by the capitalist who caused the problem, but by society as a whole, and by every living being on Earth.

Other capitalists are running this same cycle. All their commodities flow into the marketplace. Competition is the major economic driving force of capitalism. Capitalists compete against each other for the sale—by out-marketing each other or by undercutting each other in price. Usually both. This puts pressure on the rate of profit to fall. To remain competitive, the capitalists are forced to continuously cut the costs of production.

Wages are the largest variable cost in most businesses, so there’s tremendous pressure on capitalists to keep them as low as possible. To accomplish this, they manipulate the economy to keep the unemployment rate at about 5 percent or higher, so there are always plenty of desperate people competing for jobs. They move their factories to countries where wages are even lower and where repressive governments prevent workers from organizing. They pressure laborers to work longer days, and they escalate productivity so that each worker produces ever more surplus value per hour.

Competition also drives technological development as each capitalist pursues ever-increasing efficiency and speed. They mechanize their factories to minimize the number of workers.

Smaller companies that can’t keep up are driven out of business or bought up by larger ones, forming monopolies in certain sectors. Four companies control 90 percent of the world’s grain production. Only ten to twelve produce most semi-conductors. Ten produce most pharmaceuticals. These monopolies can control prices to counteract the falling rate of profit. So while the local hardware store is failing, large oil companies are making more money than ever.

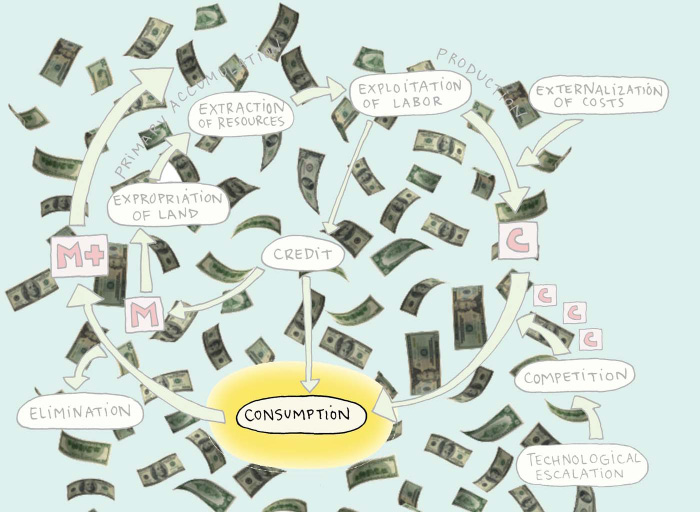

The surplus value, or profit, created in production is locked inside the commodity until the moment of consumption. When you plunk your dollars down to buy the hair dryer or the box of frozen waffles, the capitalist’s goal is realized.

Now we run into capitalism’s major contradiction. Because the workers are collectively paid less than the total worth of commodities that they produce, there will always be more on the market than what can be consumed by the domestic population. This causes what’s called the crisis of over-production. There’s too much stuff, and because profit is created by exploiting labor, the people will never—can never—be paid enough to buy it all.

The goal of each individual capitalist is to maximize profits, in other words, to accumulate as much surplus value as possible. But for the system overall, too much surplus value causes problems. It can’t all be absorbed back into the economy.

What do they do with it? They can’t just leave it lying around to depreciate; they have to get rid of it somehow. A portion is siphoned off for personal use by capitalists, to furnish extravagant lifestyles with excessive salaries and bonuses. Also, they must force open and seize control of more markets. This is one of the driving forces for imperialism. When more than one country does this, major inter-imperialist conflicts ensue.

Some surplus value is simply thrown away, eliminated through waste, wars, and so-called international “aid.” The latter two also function as centers for creating even more profit, which they pursue, but which also exacerbates the overall problem.

They increase the level of consumption with infusions of credit, basing the consumer economy on debt. Of course this creates bubbles and instability, which grow progressively worse.

Back at the start, the surplus value has to be reinvested. It must be more than they started with, because only through expansion can each company gain a competitive edge over all the others. For capitalism as a whole to function, it must grow about 3 percent annually. So the cycle goes around again, but bigger. In the next turn, they must extract more raw materials, exploit more labor, manufacture more products, generate more waste, make more profits.

This isn’t easy; as economies become saturated, there’s less opportunity for profitable investment. So they have to invent ways to turn more things into commodities, invading us through privatization and monetizing every aspect of our lives, from our emotions to genetic material.

As we know, you can’t have infinite growth on a finite planet. Today the crisis of overproduction has become acute and the system is maxed out. It’s reaching the end of all physical limits.

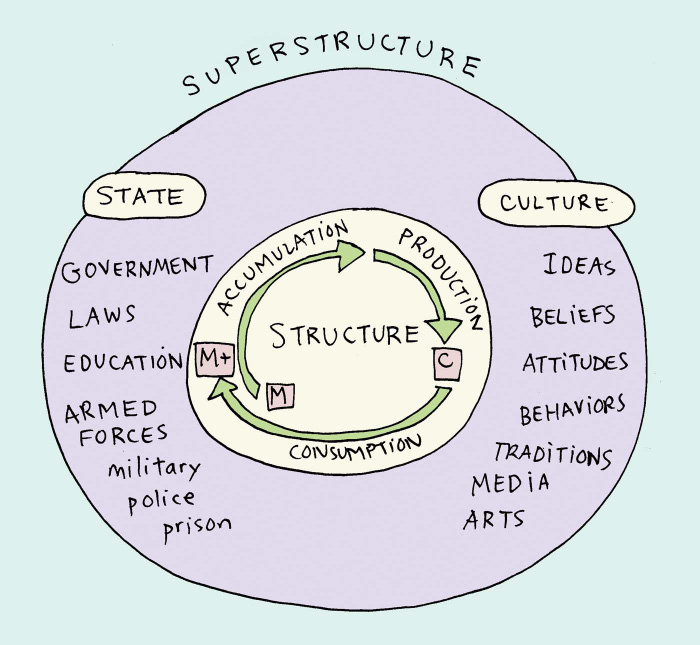

You may wonder why anyone would put up with this miserable nightmare for even one second. They do because of the superstructure—ideas and institutions that we can picture as a shell around the economic structure, both supporting it and shaped by its needs.

The sole purpose of the state is to keep the flow of capital running smoothly. It administers and regulates the process with its government and legal system. It enforces it with its military, police, prison complex, and security apparatus.

The culture also serves capitalist interests. The only ideas allowed to participate in the market are pro-system; any others are starved of support. The dominant culture tells us how to think and behave through the stories and myths of mainstream media, entertainment, and religion. It indoctrinates us in its schools. Its traditions train us in habits of individualism, competition, and subservience to authority. Its ideologies reinforce structural oppression such as misogyny, racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and nationalism. The nuclear family is a self-policing social unit enforcing the domination of children and women.

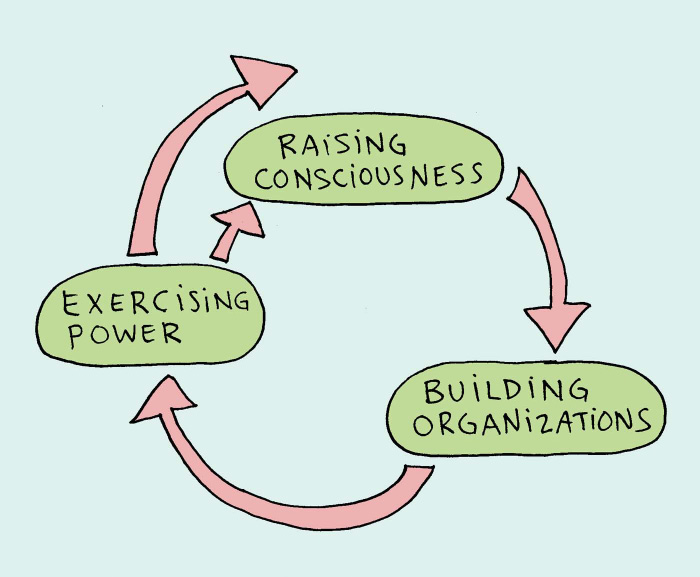

We need to break through this superstructure to choke off the flow of capital.

The conversion of nature into commodities is intertwined with the exploitation of human labor; one can’t happen without the other. Similarly, the fight to defend the land and traditional land-based ways of life is also connected to the fight for an end to exploitation, a classless society. One can’t be won without the other. When we understand this, liberating ourselves and saving the planet become the same act.

Capitalists have been very good at dividing the interests of the workers from the environment. This is, of course, intentional. After the Gulf oil spill, workers demanded that oil rigs open back up because they needed jobs to survive. Yet these are the very same people being poisoned by the externalization of costs.

This is a bind that workers have been placed in. It can only be resolved by the overthrow of capitalism and taking back our means of subsistence. We don’t need jobs at all—in fact that just helps the capitalists. What we need is a sustainable way of life.

Two ideological elements are essential at the revolutionary core: biocentrism and class consciousness. The major flaw of the class struggle has been anthropocentrism, a total focus on human needs and a utilitarian view of nature. The major flaw of environmentalists and, frankly, the labor movement as well (which has been mostly destroyed, or co-opted by sold-out unions) has been a lack of class analysis and understanding of capitalism as a system that we need to defeat. Instead, many fall victim to illusions of reformism, bourgeois democracy, technotopianism, lifestylism and other bogus schemes.

As the revolutionary project gains common experience, these movements will cross-pollinate, come closer together in their struggles against their common enemy.