CHAPTER 3

Out of the Body!

When Bob Monroe decided to sort out his notes on his out-of-body experiences for the book he intended to write, he had no idea of the impact this book would have. Nevertheless, his stated purposes for wanting to publish the record of his experiences were not especially modest. First, he expressed the hope that, by reading it, others who had traveled out-of-body would find comfort in knowing that their experiences were not unique and would have their fears assuaged by the knowledge that they did not need treatment and were not going mad. His second, more ambitious, purpose was to encourage science to expand its horizons, “to open wide the avenues and doorways intimated herein to the great enrichment of man's knowledge and understanding of himself and his complete environment.” At the same time, he was concerned that, as president of a large and successful corporation, he could be criticized, and perhaps ostracized, by his board of directors, who might well think that such an apparently unstable person was ill-suited to run a multimillion-dollar business. As it turned out, his concern was unnecessary. Not only did his fellow directors make no comment, but soon after the book was published his chairman's wife asked him to autograph her copy. Then the chairman himself drew him aside, telling him that his own wife had psychic powers, adding that he always consulted her before making an important deal.

Journeys Out of the Body, first published in 1971, dealt with events that occurred between 1958 and 1963. But in his foreword to the 1977 edition, Monroe declared that nothing had to be altered in the light of later experience. He had always recorded his out-of-body journeys in note form when he felt himself securely back in his physical body and had written them up as soon as possible afterwards. He expressed the hope that his readers would accept his accounts as they stood—as accurate records of out-of-body experiences, no matter how bizarre they might seem. The reviews were mostly favorable, and although sales were slow to begin with they soon gained momentum. The book has been reprinted almost every year since its initial publication, with sales to date approaching a million copies, and it has been translated into several languages.

Not content simply to record his experiences, Monroe devoted one-third of the book to discussing and analyzing them. He also included two chapters of instruction for those who wished to experience the out-of-body state themselves. As an epilogue he reprinted a report on a psychological investigation to which he had submitted himself at the Topeka Veterans Administration Hospital, together with the results of a physical observation and brainwave analysis carried out in the hospital's psychophysiological laboratory while he put himself into the out-of-body state. The researchers, directed by Dr. Stuart Twemlow, chief of Research Service, were mainly interested in discovering what they could about the relationships between his personality and his out-of-body experiences. They found him to be “the almost traditional businessman and father who is not a freak, does not wear unusual clothes, and does not constantly put himself on-stage for examination of his special abilities.” They added: “He pursues relentlessly his own research, makes his own contacts, and takes responsibility for his own life,” and commented on “his high sense of purpose, and his need for and relentless desire for understanding.” Their investigations revealed nothing untoward in his personality. The result of all this is that Journeys Out of the Body stands as a comprehensive account of the phenomenon as experienced by someone who, as Professor Tart says in his introduction, “is unique among the small number of people who have written about repeated OBEs, in that he recognizes the extent to which his mind tries to interpret his experiences, to force them into familiar patterns. Thus his accounts are particularly valuable, for he works very hard to try to ‘tell it like it is.’”

A phrase that Monroe frequently used in response to questions about his experiences is “go find out for yourself.” Such experiences are unique to the individual. Reality in the out-of-body state is likely to depend on, or be conditioned by, the individual's own belief system. Monroe, however, impresses as a methodical reporter and his accounts are not influenced by anything he had previously heard or read. One indication of this is his refusal to use the word astral, as in “astral travel” or “astral exploration,” expressions frequently employed in previous, and many subsequent, accounts of out-of-body journeys. As he said, “the word ‘astral’ has dim origins in early mystical and occult events which involve witchcraft, sorcery, incantations,” and he was always careful to avoid any such association.

As Monroe describes it, in the spring of 1958 he was experimenting with a technique to promote learning during sleep. For this purpose he had designed a tape carrying a combination of verbal instructions and sound signals intended to relax the listener and encourage retention and recall. He listened to the tape, had brunch with the family, and then about an hour later was seized with a cramping pain just under his rib cage. This lasted for about twelve hours, leaving him feeling sore but with no other after-effects. Three weeks later he was resting on a Sunday afternoon when he sensed that “a beam or ray” entered from outside and struck his body, causing it to shake or vibrate. This happened several times in the next six weeks. Not surprisingly, he found this worrying and arranged to have himself medically checked, but there was no sign of any illness or malign condition. These inexplicable vibrations continued to occur from time to time over the following months, always when he was lying down ready to go to sleep.

The first indication that something else was going on came when he was lying in bed on a Sunday night. The vibrations, which he was now finding rather tedious, began once more. His arm was draped over the side of the bed, with his fingers touching the rug. Idly, he moved his fingers, pushing them against the rug. They seemed to go right through the rug and touch the floor beneath. Then his fingers went through the floor and he could feel what he took to be the upper surface of the ceiling of the room below. He could feel a small chip of wood, a bent nail, and some sawdust. He pushed harder and his arm seemed to penetrate the ceiling and his hand felt water. Suddenly, he awoke, becoming aware of the moonlit landscape through the window and himself lying in bed next to his wife, while at the same time his arm was stuck through the floor, his fingers playing with water. The vibrations faded. He pulled his arm out of the floor, got up, and switched on the light. There was no hole in the rug or the floor and no water on his hand. It was, he thought, a hallucination.

About four weeks later, he was again aware of the vibrations while lying in bed with his wife asleep beside him. He was thinking about taking up a glider the next afternoon when he felt something pressing on his shoulder. He felt behind his shoulder and found a smooth wall. At first he thought he had gone to sleep—as he later realized he had—and fallen out of bed, landing propped up against the wall. But he could find no windows, furniture, or doors. Then he became aware that what he was touching was the bedroom ceiling. He was floating against the ceiling! He rolled over and looked down. He could make out the bed with two figures lying in it. His wife was one—and he was the other!

At first he thought he was dying—that somehow the vibrations were killing him. He managed to dive down into his body and found himself again beside his wife in his bed. But what had happened brought him to the verge of panic and it was some time before he was able to overcome the fear that this experience evoked. Was he physically or mentally ill? Was there any meaning to what was happening to him?

A few days later he had himself fully medically examined, including an electroencephalograph (EEG) analysis. Nothing seemed to be amiss, so his doctor gave him tranquillizers and sent him home. He discussed what was happening to him with his friend, Dr. Foster Bradshaw, who told him to try to repeat the experience, casually remarking that some yoga practitioners and followers of Eastern religions claimed they could leave their bodies and travel whenever they wished. It took some time before Monroe overcame his natural resistance to experiment willfully. Eventually, he determined to try, going to bed and after some time willing himself to leave his body and float around the bedroom, returning to his body when he felt ready to do so.

His conversations with Dr. Bradshaw led Monroe to formulate an explanation as to what was happening to him. Dr. Bradshaw, he says, had given him the clue he needed—that he was performing “astral projection”—leaving his physical body for the time being and traveling around in a nonmaterial or “astral” body. Rejecting the word astral, Monroe adopted the term Second Body to describe the non-physical body that he seemed to possess. The condition when he was no longer resident in his physical body he described as the Second State. At this time he knew of no one else who had reported similar experiences and therefore came to think of himself as unique.

To begin with Monroe was fearful of what might happen to him if the episodes continued. He was wary of being treated as a patient if he discussed the matter with the doctors whom he knew as friends, and of being regarded as a freak or psychotic if he mentioned what was happening to him to his business acquaintances or to people he knew in the local community. He embarked on a survey of religious writings to see if they contained any helpful information. This proved negative; he found, he said, the Bible too concerned with judgment and the Eastern religions mainly involved with lengthy processes of spiritual development. He was also disappointed with what he called “the underground,” divided into the professionals, ranging from parapsychologists to fortune tellers, and the consumers, dedicated believers in the potential of man's inner self and preoccupied with matters psychic or spiritual. In reviewing the literature, he discovered that most of the reported out-of-body events were spontaneous and happened once only, often when the individual was in ill-health physically or emotionally. He found no useful research and no proper experimental work and the concrete data he was searching for did not exist. In much of the literature, the analytical and empirical approach he sought was submerged in what he called “the vast morass of theological thought and belief.” The road ahead—the purposeful exploration of the Second State—was one he would have to travel alone.

Throughout Monroe's accounts of his early out-of body experiences we are aware of his efforts to make sense of what was happening. This is very apparent in his preoccupation with the reality of the Second Body. When he found himself able to induce the out-of-body state, he tended to confine his explorations first to his immediate environment and later to the surrounding neighborhood. It seemed to him that he could feel his physical body with his non-physical hands, that he sometimes met resistance when moving through a wall, and that on one occasion when he paid an out-of-body visit to a friend some eight miles away she appeared to be frightened. When he met his friend the following day, she told him that the evening before she had noticed something “hanging and waving in the air”—resembling “a filmy piece of grey chiffon”—on the far side of the room. She thought it might be him and asked if it was would he please go home and not trouble her. Then it vanished.

From these various experiences Monroe deduced that the Second Body had weight and a small degree of gravitational attraction. Under certain conditions it became visible. Its sense of touch was similar to that of the physical body. It was plastic, in that it could take whatever shape or form the individual desired. From some episodes he thought it possible that the Second Body was a direct reversal of the physical (left to right and toe to head). It was connected with the physical body by a cord that could convey messages from one body to the other and was capable of extreme elasticity. He also felt that the Second Body was affected by electricity and electromagnetic fields.

Monroe's concept of the Second Body arises from his attempts to rationalize his experiences. Reading his first book, one becomes aware of the tension between the experiences themselves and the author's attempts to explain them, to make them fit, bizarre though many of them are, into a frame or a pattern, something that the intellect can get hold of. He seems to be searching for some physical explanation, to associate the OBE with the cramping pain or the vibrations that occurred months before his first experience. The cord that he describes connecting the two “bodies” is another example of this. Mention of a cord appears frequently in the pre-Monroe literature, often being related to the silver cord in the biblical book of Ecclesiastes, and sometimes accompanied by the assumption that if it is broken both “bodies” will die. As the years pass, however, references to this cord become rarer and eventually disappear altogether, as they do in Monroe's later books. One explanation is that the cord is a mental construct: that the mind, seeking to make sense of what is happening, creates this tangible link between the body and the out-of-body as a sort of safety mechanism.

Once he was convinced that his experiences were not indicators of illness or insanity, Monroe felt able to discuss them with various friends and acquaintances. That these individuals were aware of what was going on in his life may help to explain their reports declaring they sensed he was around their houses from time to time. The oddest report comes from an episode in 1963, when one Saturday Monroe decided to travel out-of-body to visit a close friend, a businesswoman he identifies as R. W, who was on vacation somewhere, although he did not know exactly where, on the New Jersey coast. He found her, together with two teenage girls, sitting in a kitchen. Monroe spoke to her and she replied; then he said he had to be sure that she would remember his visit. He pinched her just below her rib cage. “Ow!” she exclaimed. He then returned to his physical body. A few days later, when R. W. was back home, Monroe asked her what she had been doing the previous Saturday. She said she had been in the kitchen in her holiday house, talking with her eighteen-year-old niece and her friend of similar age. She could not recall anything of Monroe's visit until he mentioned the pinch. “Was that you?” she asked, astonished. She lifted the edge of her sweater and pointed out “two brown and blue marks at exactly the spot where I had pinched her.”

Monroe's earliest explorations were confined to what he calls Locale I, the material world, its people and places, especially those in the surrounding neighborhood. He would fly over the area, choose a house whose occupiers he knew, and call in to see what was going on—and, he says, sometimes engage in a kind of conversation. To prove the validity of the experience, he often tried to collect what he called evidential data. Still at this period convinced of the existence of a real Second Body, he felt the need to prove beyond doubt that his observations were accurate and that the conversations he reported actually took place. Whether he succeeded in his objective has to be left to the judgment of his readers.

While Locale I was familiar and nonthreatening, Locale II, where Monroe's experiences soon began to take him, was quite different. He describes it as “a non-material environment with laws of motion and matter only remotely related to the physical world. It is an immensity whose bounds are unknown (to this experimenter), and has depth and dimension incomprehensible to the finite, conscious mind. In this vastness lie all the aspects we attribute to Heaven and Hell, which are but part of Locale II. It is inhabited, if that is the word, by entities with various degrees of intelligence with whom communication is possible.” In this world, linear time does not exist and measurement and the laws of physics do not apply. Thought is action, and reality is composed of “deepest desires and most frantic fears.” In many respects Monroe might be describing the world of dreams and he does suspect, he says, that many, perhaps all, humans visit Locale II at some time during sleep. On occasion he seems to be uncertain whether a particular experience was a dream rather than an exploration out-of-body, and sometimes he finds it difficult to distinguish between the two.

In later years, when Monroe describes the experiences of himself and others in Far Journeys (1985), the line between the dream and the out-of-body experience becomes much clearer. At this early stage, before he, with others, had developed the technology that enabled such a distinction to be made, he tends to gloss over the problem. But whatever the definition of the experience in Locale II may be, he is able to reach certain conclusions. His first visits to Locale II brought out various repressed emotional patterns, of which fear was dominant. In order to cope in this Locale these emotional patterns had to be controlled. He deduced that in that area nearest to the physical world are beings who are insane, or nearly so, drugged, “alive but asleep,” or physically dead but still dominated by the need for sexual release. In another part of Locale II Monroe found a park with lawns, trees, flower-beds, paths, and benches, where those who had recently died were resting and waiting to be taken on the next stage of their journey.1 Elsewhere he came across cities, armies, scenes of activity of different kinds but without any context—such as you might find idly flicking through television channels, pausing for a few seconds and then moving on. At times on these journeys helpers appeared to him, who seemed to understand what he needed but whom he could not identify. He also reports periodic visitations by a mysterious authority figure, at whose passing everything comes to a standstill and each living thing lies down in an attitude of submission. As this figure proceeds, “there is a roaring musical sound and a feeling of radiant, irresistible living force of ultimate power that peaks overhead and fades in the distance.” Monroe adds, “I remember wondering once what would happen to me if He discovered my presence, as a temporary visitor. I wasn't sure I wanted to find out.”

One particular problem, which he described as “a tricky matter” that disturbed Monroe in the earlier days of his OBEs, had to do with sexuality. Almost all of his experiences at the time took place when he was in bed with his wife Mary. On one occasion in his out-of-body state he tried to awake her to make love—but fortunately for her peace of mind she did not respond. His desire kept recurring and he began to feel disgusted with himself for being unable to shut it off. He found a solution when a recollection of what was known as the “Gene Autry love scene,” familiar to adherents of the popular Western films of the time, came into his mind. After the cowboy hero had saved the girl from the villains, they would wander across to the corral fence, gaze into each other's eyes, and, just as the audience expected the couple to join in a long and loving kiss, Gene would pull out his guitar and say, “First I want to sing you a little song,” which was usually about horses. After the song the kiss never took place because the picture ended. For Monroe this proved a model—delay rather than deny. It worked.

However, Monroe certainly found that sexuality was sometimes present in the out-of-body state. He describes its fulfillment as “not an act at all but an immobile, rigid state of shock where the two truly intermingle…in full dimension, atom for atom.” It is, he adds, as if there takes place a short, sustained electric or electronic flow from one to another. “The moment reaches unbearable ecstasy, and then tranquility, equalization, and it is over.” Both participants are out-of-body when this occurs. Monroe, who was in some respects very much the old-fashioned Southern gentleman, did not pursue the topic into further detail, declaring that most of the material in his notes was “too personal” for him to relate.

The experiences that were of special importance to Monroe were those when he appeared to find himself at the farthest distance from the everyday world. There were three occasions in September 1960 when he reports being penetrated by what he describes as an “intelligence force” to which he feels he is inextricably bound by loyalty—that he always had been so bound, and that he had “a job to perform here on earth.” This intelligence force was far beyond his understanding; it was cold and impersonal, unemotional and omnipotent. “This may be the omnipotence we call God,” he says. Then on awakening in the early morning he found himself crying, “great deep sobs as I have never cried before.” He continues: “I knew without any qualification or future hope of change that the God of my childhood, of the churches, of religion throughout the world was not as we worshiped him to be—that for the rest of my life, I would ‘suffer’ the loss of this illusion.”

Yet there were contrasting experiences also in those earlier days. On three occasions in the out-of-body state Monroe found “a place of pure peace, yet exquisite emotion,” that he equated with Heaven or Nirvana. This was a place where ultimately you belong, where there is music, beauty, and love, where you are in perfect balance with others—in short, where you are Home. From here he was reluctant to return, feeling lonely, nostalgic, and even homesick when he reentered the physical world. Both the intelligence force and Home reappear in Monroe's later experiences, yet at the time he described them he would have had no idea of how things would develop.

While Locale II has certain similarities to the dream state, Monroe's Locale III, which he came across early in his explorations, is quite different. He describes a series of experiences that took place between May 1958 and February 1959 that introduced him to this “alternative world,” altogether unlike anything he met with in Locale II and quite closely related in many respects to Locale I and the everyday physical world of his waking hours. In analyzing the nature of his experiences, Monroe records that only 8.9 percent of his journeys took him into Locale III, compared with 59.5 percent in Locale II and just over 31 percent in Locale I.

Monroe discovered Locale III quite involuntarily. One afternoon in May 1958 he sensed the vibrations that seemed to preface an out-of-body excursion, but found himself unable to lift out of the physical. He rotated his Second Body through 180 degrees and became aware of an endless wall with a hole that appeared to be the shape of his physical body. The hole also appeared to be endless so that he felt he was looking into the blackness of infinite space. He moved into the hole but found nothing but this blackness. Disturbed, he withdrew, returned to his physical body, and sat up. Checking the time, he found he had been “out” for over an hour although it felt as though only a very few minutes had elapsed.

In the following weeks Monroe explored the hole further. Reaching through it, he felt his hand taken in a friendly clasp by what seemed like a warm human hand. On one occasion he was given a card with an address on it; on another it was a hook, not a hand, that he encountered. Once when he put both his hands into the hole they were grasped by two other hands and a female voice called his name: “Bob! Bob!” He resolved to explore further, traveled right through the hole, and found himself in a landscape with a building nearby that resembled a barn and near it a tower about ten feet tall. He ascended the tower, jumped off, and instead of finding himself flying, as he felt would happen, simply fell to the ground. Exploring further, he saw a man and a woman sitting by the building. The woman seemed to know he was there but did not communicate.

Further experiments in visiting Locale III enabled Monroe to produce a coherent picture of what he took to be “a physical-matter world almost identical to our own.” He observed “trees, houses, cities, people, artifacts…homes, families, businesses…roads, railroads and trains.” Yet this world in many respects was very different from the world in which we live. There was no electricity, no internal combustion, gasoline, or oil. The locomotives were steam-driven but the steam, so he understood, was created by some form of radiation. He could not make out how the motive power for the large, slow-moving automobiles was provided, but noted that they lacked tires and were steered by a single horizontal bar.

At first the people in Locale III were unaware of Monroe's existence. But then, quite without intention, he found himself on these visits merging with a person living in this different universe. This was a rather lonely architect-contractor who lived in a rooming house, worked in a city that he did not know well, had few friends, and traveled to work by bus—a wide vehicle seating eight abreast with the seats rising in tiers behind the driver. No fares were charged, as Monroe discovered when once he tried to pay. In these experiences Monroe took on this man's activities, memories, and emotional patterns, although all the time he was aware that he was not him.

In subsequent visits, Monroe (or “I There,” as he describes himself in this other life) met a wealthy woman called Lea, mother of two young children, whom he made friends with. She was a sad and withdrawn person who had recently suffered some tragedy, although he never knew the details. Eventually Monroe “I There” and Lea married and moved into a large house, where he had a workroom. On occasions he found himself in awkward circumstances, usually when he was ignorant of something he ought to have known. To escape from embarrassing Lea or himself, and to avoid suspicion (presumably of “I There” being thought to be insane) he would move back immediately to his own physical body, allowing Lea's “real husband” to return.

When he was resident in his physical body, Monroe had no way of telling what was going on in his life in Locale III. There were times when he moved in to Locale III at a difficult moment, as on one occasion when Lea and the children were riding in a self-propelled vehicle on a mountain road. He took over the driving but, unaccustomed to the vehicle, he rolled it off the road into a pile of dirt. On a later visit he found that Lea and “I There” had separated. He was greatly saddened and strongly desired to visit her. She gave him her new address, but he lost or forgot it. On the last visit he describes, he found “I There” lonely and unhappy, searching for Lea and the children but failing to find them.

This life as “I There” was not an enviable one—not a life Monroe would in any sense have chosen to live. Among the many questions his narrative raises is what happened to the “I” of the architect-contractor when Monroe took him over. Did these intrusions cause him embarrassment or distress? Did he perhaps think he was subject to moments of forgetfulness, or even insanity? How was it that no one seems to have called him by his name? Another interesting point is that Locale III, which Monroe describes in much detail, does not appear to fit into any period of the Earth's history and in no way does it seem to be attached to Locale II. In trying to establish its reality, Monroe wonders if it might be “a memory, racial or otherwise, of a physical earth civilization that predates known history.” Other possibilities he mentions are “another earth-type world located in another part of the universe which is somehow accessible through mental manipulation,” or “an antimatter duplicate of this physical earth-world where we are the same but different, bonded together unit for unit by a force beyond our present comprehension.”

Strange though it may seem, however, Monroe's experience of an “I There” is not unique. Professor J. H. M. Whiteman, a mathematics professor at Cape Town University and author of The Meaning of Life: An Introduction to Scientific Mysticism (1986), suggested the term mediate identification to define a situation “in which one finds oneself in a tangibly real three-dimensional scene, with a human form and disposition quite unlike what other people would take us to be physically, and with memories appropriate to the situation in which one finds oneself.” Whiteman claimed to have experienced between sixty and seventy such instances himself, when he moved into what he calls “secondary separation,” which seems to be no different from an out-of-body state. To give just one example: he found himself as the recently married wife of a captain of a ship, sailing on a kind of delayed honeymoon trip and feeling extremely contented. Then as he joined the company for breakfast at the captain's table, he—the wife—became disturbed by the facial expression of a man sitting at the table who seemed to be resentful of the presence of a woman on board but at the same time to be personally interested. Shaken by this, he returned to his physical body.

In his analysis of this and other comparable experiences, Whiteman distinguishes four different kinds of entry into another person's life: physical (entering the life of a person in today's world); nonphysical (entering the life of someone not physically alive); fictional (entering a fictional scene, as if in a novel or play); and retrocognitively (entering a scene in a nonphysical world based on individuals’ or cosmic memories but so effective as to appear to be a “present living reality”). In Monroe's books instances of all of these occurrences may be found.

However, whereas Whiteman's experiences appear to be singular in that he does not visit a particular location more than once, Monroe's are repeated. Once he is through the hole, the world he inhabits is consistent no matter how often he visits, and the life story he leads there is continuous and coherent. His experiences can be contrasted with those of two instances of other individuals who have reported dual lives. One of them, a female social worker, for several months would lie down in the evenings after work and find herself living a parallel life as a male medical student residing in a strange town and traveling each day to lectures and classes, returning in the evening to continue studying or occasionally going out to try to develop a social life. The other, a teacher's wife, would withdraw for hours or sometimes days at a time to live a contrasting life of excitement and challenge with a wealthy gangster somewhere in Europe. Both these women, like Monroe and Whiteman, were able to induce out-of-body experiences to continue with their alternative lives.

Monroe's experiences in Locale III seem to have ended after 1960. He gives no sign of wanting to continue with them; it is as if that particular chapter was closed and the story, as far as it went, was over. Yet in the light of theories and ideas about the existence of parallel universes—see, for example, physicist Fred Alan Wolf's Parallel Universes—Monroe's documentation of Locale III may in time come to have a relevance he could never have imagined.2

Not all of Monroe's out-of-body journeys fitted neatly into one of the three Locales. He quotes a few instances of what appear to be precognition, some of which turned out to be accurate. One included a description of the interior of a house where, years later, he and his wife came to live. There were also disconnected scenes of happenings—some in recognizable environments and some not—in which he played a part. These might be interpreted as snapshots of past-life experiences, although he does not define them as such. Often he was glad to return to his physical body after such experiences, most of which did not fit into any recognizable context.

In the closing chapters of Journeys Out of the Body Monroe provides advice and instructions for those who wish to experiment for themselves. He is convinced that most individuals, if not all, leave their physical bodies during sleep, although what he calls the “conscious, willful practice of separation from the physical” is not in accordance with a natural sleep pattern. He warns his readers that once they have opened the doorway to this experience it cannot be closed, and that what they will discover will be “quite incompatible with the science, religion and mores of the society in which we live.” Nevertheless “something extremely vital” will be missed if this exploration does not take place.

Fear, Monroe maintains, is the only major barrier to out-of-body exploration. There are several reasons for this. Separating from the physical body is what is usually expected to occur at death. Hence, it is natural to feel the necessity of getting back into the body lest you die before you can reenter it. Associated with this is the fear that you may not be able to return to the physical; that once out you may never get back in and will be fated to roam around in the unknown for all eternity.3 There is also the fear of the unknown itself; nothing that you have learned or experienced in ordinary life will help you find your way in this totally different environment where the rules do not apply and the map does not exist. Lastly, there is the fear of the effects of the experience on the physical body and the conscious mind. Is there something wrong with you? Are you going mad? It was some time before Monroe came across anyone else—a “normal” person—who had experienced out of-body travel. When eventually he did so he was greatly relieved.4

After October 1962 the frequency of Monroe's out-of-body excursions diminished. He felt that this was because he was more involved with material affairs and also with evaluating the experiences of the previous four years. He found that the vibrations that in earlier years preceded separation from the physical ceased to occur. He was no longer troubled by fear in the journeys he undertook to Locales I and II. Then, towards the end of the period, he began experimenting with the process under observation in laboratory conditions. Reflecting on his experiences to date, he recorded two conclusions. First, while in the Second Body it was possible “to create a physical effect on a physically living human entity while the latter is awake.” Second, “there are unfolding areas of knowledge and concepts completely beyond the comprehension of the conscious mind of this experimenter.”

Despite this second conclusion, Monroe presents a statistical analysis of the 589 out-of-body experiences he recorded over the twelve years between his first OBE and the completion of the text of his book. Here he is striving to organize the material he has recorded in his notes, to fit it into categories, to provide evidence, and to make it scientifically acceptable. He also describes a couple of unusual incidents that happened in his childhood and youth and speculates as to whether dental work he had undergone, anesthesia and other inhalants, and the use of the auto-hypnotic tapes he created to experiment with sleep-learning might have been relevant to instigating his first out-of-body experiences. He details the physical symptoms—the feeling of constriction, the vibrations, the awareness of a kind of hissing sound—that in the early days prefigured an out-of-body episode, but which became less obvious and eventually ceased as the episodes continued.

Monroe also seeks to distinguish the Second State from dreaming, declaring that in dreaming “consciousness as the term is understood is not operative,” while in the Second State “recognition of ‘I am’ consciousness is present.” However, this distinction does not hold up in the light of subsequent work on lucid dreaming, which purports to show that the lucid dreamer is aware that he is dreaming and is able to exert conscious control of the dream. This leaves the question open as to whether at least some of Monroe's Locale II experiences might have been lucid dreams. He does himself go so far as to say that if any experience did not contain a majority of the conditions he lists as defining a Second State category, then he would consider it as a dream.

Monroe's own ideas and beliefs during the second half of his life were strongly influenced by his out-of-body experiences. Perhaps the most significant of these influences is his acceptance of some kind of immortality. While he does not propose that everyone who dies automatically moves into Locale II, or that one's afterlife presence in Locale II continues forever, he is convinced that this is the destination of most of us after our physical death. Although Locale II is not centered on the Earth, he suggests that there is some form of contact with our physical world that provides a means of entry. It is through this portal that we proceed after we die.

This belief in some form of afterlife derived from a series of encounters that he describes in a chapter he entitles “Post Mortem.” The first was with his close friend Dr. Richard Gordon. He had been lunching with him in the spring of 1961 and noticed that Gordon was looking ill. Gordon admitted he was feeling below par but said that he was about to leave with his wife on a European holiday and would seek advice when he returned. Six weeks later Mrs. Gordon called Monroe to say that the doctor had been taken sick and they had returned home. Soon afterwards he was diagnosed with abdominal cancer. Monroe wanted to see him but was told he was too ill and under deep sedation. His wife suggested that he write to him and she would read him the letter when he was conscious.

In this letter Monroe outlined his own out-of-body experience and suggested that Dr. Gordon might accept the possibility that he could “act, think and exist without the restriction of a physical body,” and that while he was in the hospital he might consider the implications of this and see if he himself could develop this ability. Some weeks later, Dr. Gordon died. Monroe waited for several months and then decided to try to contact his friend, despite the possibility that the experiment might be dangerous. He moved himself into the out-of-body state with the intention of somehow finding Dr. Gordon. He felt he was being guided into a room where three or four men were listening to a younger man with a big shock of hair who was excitedly relating something to them. A voice said, “The doctor will see you in a minute.” Monroe began to feel uncomfortably warm and decided he could not wait. Then the young man stopped talking and turned to look intently at him before continuing his discussion.

Monroe moved away and returned to the “in-body” state, feeling he had failed. The following week he decided to try again and was surprised to hear a voice saying, “Why do you want to see him again? You saw him last Saturday.” On checking the notes he had made on his earlier attempt, he realized that the man who had looked intently at him was indeed Dr. Gordon in his early twenties, a realization that was confirmed when he later saw an old photograph of Gordon at the age of twenty-two, and when Mrs. Gordon said that when she had first met her husband he often talked excitedly and was proud of his big shock of hair.

In this same chapter Monroe relates two further encounters with individuals who were physically dead, concluding with an episode with his father, who died in 1963 at the age of eighty following a stroke that left him paralyzed and deprived of speech. Months later Monroe woke up about 3 A.M. and felt he should try to visit his father. He found him in a room in what might have been a hospital or convalescent home. His father, now a younger man, turned to him, seized him under his arms, and swung him over his head, just as he used to do when Monroe was a child. Then he moved away, as if he had forgotten his son was there. Monroe left the room and soon returned to his physical body.

These and similar experiences led Monroe to the conclusion the Second Body—or whatever it is that can leave the physical body and return again—can survive “what we call death” and that personality and character “continue to exist in the new-old form.” His three visits to the “place or state of being” that he called Home, “where you truly belong,” relieved him from any fear of what might happen after the cessation of physical life. He adds also that he was aware in many of his OBEs of someone or something who helped, but whoever or whatever his helpers were he could not tell. Subsequent experiences, as detailed in his later books, illuminate these discoveries, but the light comes in from a rather different angle.

Having worked with Monroe and others and examined a large number of accounts and reports from a variety of sources, Professor Charles Tart emphasizes the significance of the out-of-body experience, pointing out that “because of the immense effect on the individual's belief system—namely, convincing him that he will survive death—the OBE is one of the most important psychological experiences, even though it occurs rarely.” He continues: “ I am convinced that most of our great religious traditions are based on this sort of experience. We will not be able to understand our religious heritage or our philosophies of life until we come to an understanding of OBEs. OBEs are one of the world's most important and most neglected phenomena. Even psychic researchers generally do not pay attention to them. But their importance in understanding man cannot be overestimated.”5

Commenting on Journeys Out of the Body, Joseph Chilton Pearce wrote that “Robert Monroe made the most systematic and intelligent exploration and reportage of this state ever recorded (so far as I know).” He added that Monroe has “an exceedingly strong, active, well-developed system of imagery transference. He had the capacity to transfer imagery over a wide spectrum, which means the capacity to perceive where ordinary, weak perceptual systems cannot. Monroe could enter a field of experience alien to our ordinary one because he has a strong and flexible imagination, images capable of transferring alien imagery into meaningful perception…I am sure that some of his reportage was only an approximation of what the states might have been to someone within those states. And he came across situations where no approximation of any sort was possible, where there were insufficient points of correspondence to make any transfer.”6

By 1976 Monroe had received more than 15,000 letters from readers of Journeys Out of the Body describing their own out-of-body experiences, with most of them adding how relieved they were not to be psychotic. In his foreword to the 1977 edition, Monroe says that having reviewed the text he was content that nothing had to be altered in the light of later experience. “From the point of my experimental level at that time,” he adds, “it is still accurate.” But his own subsequent experiences and the experiences of others that he records in detail in Far Journeys (1985) open more perspectives on the nature of the out-of-body experience. In one quite important respect, his preoccupation with the physical reality of the Second Body has almost vanished and his understanding of the nature of consciousness has deepened considerably. Nevertheless, Journeys Out of the Body remains a classic in its field and has both comforted and inspired countless numbers of readers who have endured experiences, sometimes disturbing or frightening, that without Monroe's help they could in no way understand.

Some copies of Journeys Out of the Body seem to have acquired a life of their own. People have reported finding it on the floor of the bookstore, or falling off a high shelf and hitting them on the head. One purchaser discovered it lurking in the cookery section and more than one came across it under “Travel.” In an interview in 1982, Monroe remarked that the book's publication gave him the opportunity to meet very many new people, which he found rewarding in itself. It also gave him the chance to come, as he said, “out of the closet, instead of being a closeted, out-of-body hidden-away person.” He continued: “It was funny the way I began to be looked upon…people would stare and look at me and say ‘Is that who he is? That's the person who goes out of his body?’ Or these strange looks, like ‘He's a weirdo’ or freak or something.’ But it was a lot of fun to see this change. And, of course, one of the most rewarding things that has taken place is the mail—the mail of people from all over the world…and the most important were the ones that said ‘Thank God, I know I'm sane!’”

In the same interview Monroe commented on the immense changes that had taken place in public attitudes over the last ten years or so. “Now it's OK to talk about out-of-body experiences as a reality. And from that point of view, we participated in the presentation last year of three papers before the American Psychiatric Association on out-of-body experiences, which ten years ago would have been unheard of. It was beyond my wildest imagination that the APA would seriously listen to a phenomenon known as the out-of-body experience.”7

Notes

1. Monroe revisited these two areas several years later, as recorded in his other two books. They also appear as Focus 22 and Focus 27 in the Lifeline program.

2. In his book, subtitled The Search for Other Worlds (Simon & Schuster, 1988), Wolf says that his reasoning leads him to the following conclusions: (1) there is an infinite number of parallel universes; (2) quantum waves carry information moving from past to present and from future to present; (3) we should be able to “talk” to the future as clearly as we “talk” to the past; (4) existence as we know it is a subset of reality that is unknowable. Think on!

3. Many times Monroe was questioned about this particular fear. His reply was always the same: “No need to worry about that. Your bladder always calls you back!”

4. Monroe visited Professor J. B. Rhine, well known for his work on extrasensory perception, to see if he could advise him with regard to his OBEs. Rhine was not helpful, but as he was leaving a young intern, who had been sitting in on the discussion, came up to him and said, “Don't worry, Mr. Monroe. I do it too.”

5. Psychic Exploration, edited by J. White (Putnam, 1974).

6. From Magical Child to Magical Teen, by Joseph Chilton Pearce (Park Street Press, 2003 [1985]).

7. A fully referenced study of the out-of-body experience, by Carlos Alvorado, may be found in the American Psychological Association's (APA) publication Varieties of Anomalous Experience (APA, 2000). The final sentence reads: “It is my hope that this chapter will inspire further research and that future discussions on OBEs will not have to be conducted solely in the context of a psychology of the exotic or the unusual, but in the wider context of the study of the totality of human experience.” Such further research, particularly in the field of consciousness studies, is taking place. Professor Charles Tart proposes a definition of the OBE as “an altered state of consciousness in which the subject feels that his mind or self-awareness is separated from his physical body and this self-awareness has a vivid and real sense about it, quite different from a dream.” Physicist Amit Goswami suggests that “the nonlocality of our consciousness” is the key to the understanding of the OBE.

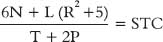

Author's Note: As a point of interest, if you asked Monroe to sign a copy of Journeys Out of the Body, instead of a “standard” message, he would often inscribe an equation. Here is an example:

Each one is unique. As far as I know, none has ever been solved or explained.