INTRODUCTION

Flying Free

Well, there are two types of deed. One is the physical deed, in which the hero performs a courageous act in battle or saves a life. The other kind is the spiritual deed, in which the hero learns to experience the supernormal range of human spiritual life and then comes back with a message.

—Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth

Bob Monroe was, on the face of it, an unlikely hero. When he set out on his hero's journey he was, as he said of himself, a fairly conventional person: a wealthy businessman with a beautiful wife and an impressive record of achievement in the highly competitive world of radio broadcasting, listed in Who's Who in America, president of this, vice president of that, with a host of opportunities opening before him. Actually, he wasn't all that conventional. His parents, each of them strong characters in their own right, were both members of professions with enough money in hand to help him on his way. Bob, however, chose to take a year off riding the rails as a hobo, then to embark on a series of jobs to pay his own way through college, and after that to share one large room in New York with three would-be actors while he sent off scripts for radio shows, most of which ended up in someone's bin. His great passions, indulged whenever he could, were flying and driving fast cars. They sound like expensive hobbies, but the aircraft he flew were mostly held together with string and tape and the fast cars he cobbled together himself. And he had one unusual distinction: when he found a girl he liked, he married her. Or so he said.

And then, at the height of his career, it all began to change. He became, of all unlikely things, and by chance rather than by choice, an explorer. The time came when the name of Robert Monroe was no longer associated with mass entertainment but with something quite different: the exploration of human consciousness. Rocky Gordon and High Adventure were long forgotten; now Robert Monroe was the “out-of-body man” or the “astral traveler.” His first book, Journeys Out of the Body, became essential reading for those interested in psychic phenomena, in postdeath survival, in the extraordinary rather than the ordinary, everyday world. Scientists from various disciplines, psychologists, psychiatrists, New Age gurus, journalists, and the merely curious came to visit him in the foothills of Virginia's Blue Ridge, where he built a research laboratory on the grounds of his country home for the furtherance of his explorations. And, as it happened, the influence of certain sound frequencies on human consciousness became the focus of his investigations. He became convinced that focused consciousness contained definitive solutions to the questions arising from human experience.

What began as one man's desire to understand what had happened to himself developed into a research project, into experimental work with volunteers, into the discovery and development of a technology capable of producing identifiable, beneficial effects, into the establishment of a residential institute with its own research laboratory—all leading to a major contribution to the exploration and understanding of human consciousness.

As an explorer, Monroe sought to create a map of the territories that he personally explored. This was a long and at times difficult and dangerous task. Lines by the Welsh poet Gerard Manley Hopkins illustrate some of the perils that he had to face:

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap May who ne'er hung there…

At the outset he found no guidance, no track to follow. He had to face the possibility that in seeking to scale those mountains his own sanity was at risk. Yet somehow he knew he had no choice. Night after night he returned to his explorations. He began to recognize certain landmarks, to gain in confidence, to fill in more details on his map. His explorations lasted for thirty-five years. As they ended, he was convinced that he had found what he was looking for—but he had not known what he was looking for until he found it.

Early on, Monroe accepted that it was his mission to provide the opportunity for others to study his map and, if they chose, to move into the open country and make their own discoveries. He designed the tools and equipment to help them on their journeys and a safe environment for them to embark from and return to. So we who are prepared to take this opportunity inch our way forward, and the open country no longer seems forbidding as our experience becomes richer and our understanding of what Joseph Campbell called “the supernormal range of human spiritual life” gradually increases.

What was the message that Monroe brought back from his explorations? If you had asked him that question, his reply would probably have been to quote the opening sentences of the affirmation that participants in the courses he designed are asked to repeat before they begin their personal explorations. “I am more than my physical body. Because I am more than physical matter, I can perceive that which is greater than the physical world.” But there is more to it than that. The audio technology that he developed as a result of his explorations trains its users to be able to move at will into different states and areas of consciousness, sharpening their perceptions and enriching their experience, and enabling them to comprehend that their physical life existence is not the only existence that is open to them.

Jill and I first met Bob in the summer of 1986. We had heard about his Institute from a somewhat unlikely married couple. He was a distinguished scholar holding a senior post in an ancient English university and his much younger wife had enjoyed many rich experiences on the West Coast of the United States. They had just returned from taking a course at the Institute and encouraged us to do the same. After much deliberation, mostly on my part, we booked in to a Gateway program that summer.

The countryside in the foothills of Virginia's Blue Ridge, some thirty miles from Charlottesville, was beautiful: swathes of grassland, tree-clad hills, neat houses tucked away in the woodland, a farm with cattle, a picturesque lake, turkey buzzards overhead, the Blue Ridge Mountains on the horizon. The Residential Center where the program took place was comfortable enough. We shared a sort of cabin with two berths, each fitted with a control panel equipped with headphones, switches, and colored lights. Most of the time was spent listening to a series of different exercises recorded on tape and discussing our experiences afterwards with the trainers and the rest of the group—twenty-two in all, and only five of them women. That was odd, for a start, as we had understood that women were usually in the majority on “life-changing” courses. And what about the participants, especially the seven Californians? Did they ever stop talking—did they ever stop telling you things?

So here we were—two matter-of-fact Brits amid a gang of fantasists. Or so at first it seemed. But it didn't stay like that for long. Soon we were fantasizing with the best of them. Then it happened— it almost always does. This wasn't fantasizing. These experiences were real—more real than anything we had experienced before. There were no drugs, no alcoholic drinks, no hypnosis—only gently modulated sound signals and a firm and friendly voice talking you through a series of exercises and giving you space and time to explore. The mind, the consciousness, which had hitherto been occupied with the matter of daily living, the details, problems, and decisions of work and family life, now was enabled to fly free, to soar and plunge and glide, to venture into areas never imagined before, to explore and discover—and then to return to report.

When the program was finished and it was time to leave, we waited to bid Bob Monroe farewell and to thank him for an experience that, as we already suspected, would change our lives. He cut us short. “Have you got time?” he asked. “How about a drive round the New Land?” We climbed into his battered four-by-four. He put his mug of tea into a holder and started up. The fuel gauge, I noticed, stood resolutely at zero. We drove off, away from the Institute buildings and along the rough road winding its way up Roberts Mountain. Bob pointed out houses tucked away among the trees, mentioning who owned them. He stopped at one particularly splendid house and took us inside. “Eleanor's just had this built,” he said. “She's away just now—she's my agent—she flies in from New York in her own aircraft. Come in, I'll show you round.”

We were impressed, as no doubt he intended us to be. It was a beautiful house, open-plan, elegantly furnished, walls lined with modern paintings, huge windows overlooking a swimming pool and the forest beyond—a dream house, despite the pervasive smell of cats. Anyway, we like cats. Then we drove on, sharing the mug of lukewarm tea, the roads rougher and narrower as we neared the summit. Occasionally, Bob pointed out parcels of land for sale. “You'd have good neighbors here,” he said, indicating one heavily overgrown patch. “A doctor owns the next-door plot.”

Then as we continued he fell silent. Yet somehow we felt that a conversation was continuing—no longer a sales pitch but something quite different. It was as if the three of us had recognized each other and were communicating wordlessly—as if we were joining him in some orbit where words were not needed for the conveyance of thoughts, feelings, visions. Whatever was happening, our intention as we arrived back at the Center was that, no matter what the cost, as soon as we possibly could we would return not only for another program, but also for the opportunity to spend more time with Bob Monroe, whose magic already held us in thrall.

So began a friendship with Bob that lasted until his death nine years later. We returned to the Institute to take a program or to attend the Professional Seminar and the advisors meeting every year—except one. That was the year we were moving house—and early in the following year he died. In between our visits we called him frequently, especially in the months after the death of his beloved wife, Nancy, whom we had come to know and love. In those conversations his sense of desolation became apparent, and he was able to express this by telephone without the embarrassment of doing so face to face.

What was he like? Complex, contradictory, multifaceted—all those terms apply. To most of those who came to his courses he was the main attraction—here was the famous traveler into inner space who came down from his home on the mountaintop to share his experiences and his wisdom. To see and hear him, to shake his hand and ask him to sign your copy of one of his books—that was something you would never forget. And he certainly possessed charisma. He knew how to hold an audience and his sense of timing was as finely tuned as that of any professional actor. Many who met him would appreciate the comment of a journalist from a local newspaper who was sent to interview him. He admitted to being somewhat apprehensive, hearing that the man he was going to meet had been described as impatient at best and autocratic at worst. But his impression different. “When I first met Bob Monroe,” he wrote, “he struck me as a cross between George Gurdjieff, the Armenian mystic philosopher, and George Cleveland, who played Gramps on Lassie.”

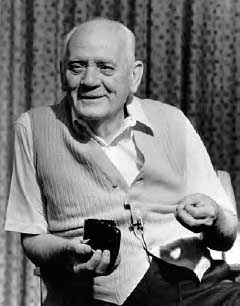

Bob Monroe, Gateway Program 1987

Bayard Stockton, whose study of Monroe was published in 1989 under the title Catapult, found three important strands in Monroe's life. The first was to search for his identity, a process that, he says, was “incredibly expensive, exhausting, frightening, lonely, selfish—and beneficial.” The second was that through his engineering approach, “he helped to de-mystify what others refer to as the occult, the supernatural or supernormal, even the metaphysical, for many other people.” The third was his success “in introducing a potent new technology in some branches of medicine, in education…and, conceivably, in business,” adding that “his tools-of-the-mind may be far more useful than has heretofore been suspected.” It is impossible to be certain that Monroe ever did figure out who he was—and that can be said, I suspect, for most of us. But the other two identifiable strands in his life have led to significant benefits, increasing year after year as the applications of his technology become more widely recognized.

As we got to know him better, and as I began to look more deeply into the story of his life, more facets of his personality were revealed. In him you could discern the competitive and sometimes ruthless businessman, the actor able to command any audience, the daredevil adventurer, sometimes pushing himself to the extremes, the wise mentor, the warm friend, and, perhaps most significant, the visionary. His judgment was not always sound and he was certainly no saint. But thousands upon thousands of people loved him.

Bob's death did not come as a shock. It was not that he had lost the will to live, but his failing health and his loneliness over his last three years, when his only constant companions were his little dog, Steamboat, and his seven cats, had drawn most of the pleasure out of his life. From his decades spent exploring the realms beyond physical life he was assured that death was simply the end of one phase of existence. You were not extinguished, nor did you stay around. You moved on.

On the Earth plane, Bob Monroe endures in the minds and hearts of those who knew him and loved him. But once he had discovered what lay beyond that plane, in those farther reaches where he had ventured and explored, there was nothing to hold him here.