Studies of the social origins and backgrounds of 18th-century army officers suggest that in 1780 some 24 percent of them were members of the aristocracy – including numerous untitled younger sons and grandsons of peers – while a further 16 percent were drawn from the old landed gentry or baronetage (which, socially, amounted to pretty much the same thing). Together, therefore, they accounted for some 40 percent of all officers, which would at first sight appear to confirm popular impressions. However, after 1800, these upper-class officers were disproportionately concentrated in the Household units, particularly in the even more fashionable Hussar regiments. This is starkly illustrated by the fact that while only 19.5 percent of first commissions were being purchased in 1810, they accounted for 44 percent of the ensigns in the Guards and 47 percent of cavalry cornets.

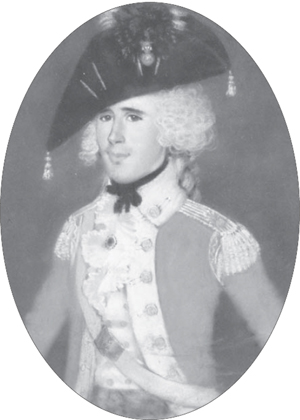

This sitter is normally identified as Lieutenant-General Simon Fraser (d.1782), but despite the distinctive Lovat features, the style of the uniform suggests he is actually another officer of that name who was promoted Major-General on 3 May 1796, and who subsequently served as a Lieutenant-General in Portugal. (Private Collection)

An interesting contemporary comment on the situation can be found in a letter written by Ensign William Thornton Keep of 2/28th in 1812: ‘Many of our Gents are restless to remove from the infantry to cavalry, particularly if at all aristocratically inclined, for the latter though expensive is considered the most dashing service, and is generally selected by young men of good fortune and family. The consequence is that officers of the infantry hold themselves in very low estimation comparatively.’ In fact, another recent study suggests that during the American Revolutionary War only 7 percent of ordinary infantry officers serving in the line were from the aristocracy, titled or otherwise, and another 5 percent from the baronetage, thereby accounting for just 12 percent of the total, as against 40 percent in the army at large.

Consequently the social distribution could be very uneven. Some regiments certainly prided themselves on maintaining a ‘select’ officer corps, while others must have been much more workaday in style. The 34th Foot, for example, were famously known in the Napoleonic period as ‘The Cumberland Gentlemen’, and John le Couteur of the 104th smugly recorded in his diary for 31 October 1814 that: ‘Sir James (Kempt) was pleased to say that He had never seen a mess so like the establishment of a private family of distinction.’ The officers’ mess of the 39th Foot in the 1740s’ on the other hand, was a much more robust establishment in which Lieutenant Dawkins once threatened to cut his major’s throat!

In peacetime the army maintained a reduced establishment in which promotions and appointments by purchase naturally predominated, but in wartime, with a greater number of casualties occurring, it was a very different matter. Not only was the creation of officers within existing regiments increased, but a whole host of new regiments were raised, all in turn requiring a steady supply of officers. If too many of those officers became casualties they too would have to be replaced by yet more aspiring heroes. The expansion of the army resulted in an exponentially large demand for officers, and since this demand was not matched by a corresponding increase of the birth-rate of the gentry and the aristocracy, the additional officers had to be drawn from a much wider social base.

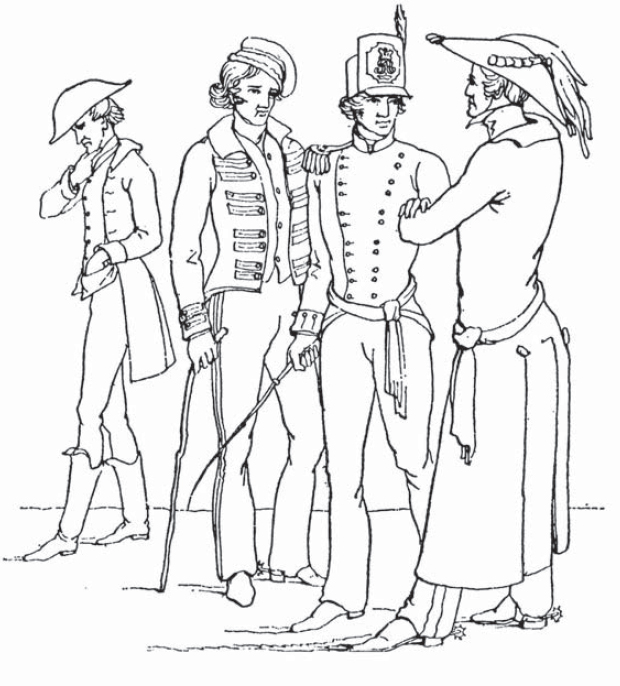

Officers in undress c. 1812 by John Luard, who served in the Peninsula with the 4th Dragoons. From right to left: an assistant surgeon in a rather short-looking frock coat, a dragoon, an infantryman and a staff officer.

While the eventual abolition of purchase in 1870 tends to be hailed as a thoroughly good thing, it actually had no discernible effect on the social composition of the British Army. By 1830 the percentage of officers drawn from the aristocracy and landed gentry had risen to 53 percent and, despite the abolition of purchase 40 years later, the Army remained firmly in the hands of what by then had become a pretty homogenous officer ‘caste’. In fact its officers continued to be drawn from that very level of society which would have been best placed to purchase commissions previously. Indeed, at the time of its abolition some opponents of purchase even argued that its removal would actually ensure the proper predominance of the landed gentry by excluding the nouveau riche with only their money to commend them.

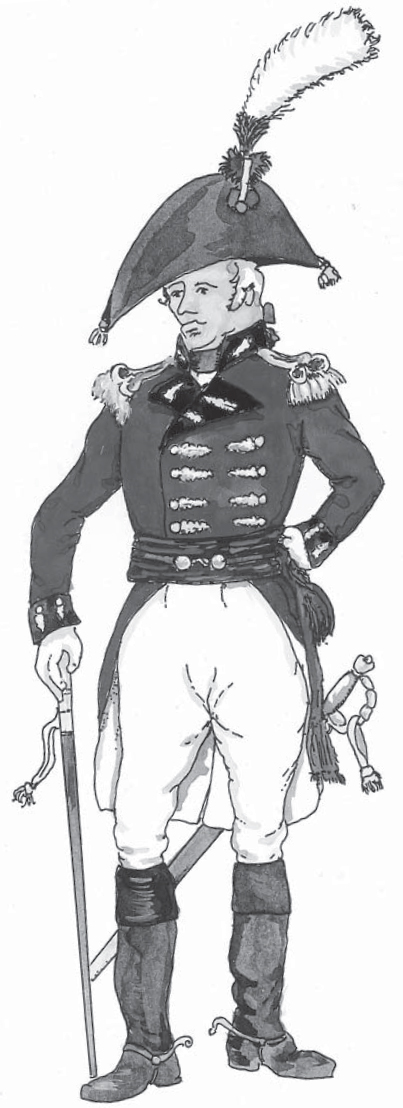

Field officer 1st (Royal) Regiment 1804 after Loftie; an interesting illustration depicting the optional (and expensive) gold thread embroidered coat allowed to be worn by those officers of this regiment.

By contrast the Georgian Army drew its officers from a far wider base than its later counterpart and was much more open to promotion from the ranks. Ensign John le Couteur was rather snobbish about this, declaring in 1812 that: ‘In those days of raging wars, all sorts of men obtained Commissions, some without education, some without means, some without either, and many of low birth.’

While all officers were officially designated gentlemen, if only by virtue of their commissions, the reality was that the majority of Georgian ones were the sons, legitimate or otherwise, of soldiers, clergymen, the professions, and even tradesmen. They were, as one of them put it, merely ‘private gentlemen without the advantage of Birth and friends’. Some of them could certainly afford to purchase their commissions, or could at least borrow sufficient money for the purpose, but all too often they lacked it and for the most part applied for non-purchase vacancies.

A significant number of officers began their military careers in the ranks. During the 1800s The London Gazette not only recorded whether a commission was purchased, but also very helpfully noted whether the recipient was a volunteer, a former NCO, or simply a private gentleman. Analysing the Gazette entries, it has been estimated that some 4.5 percent of newly commissioned subalterns were volunteers – young men who served in the ranks, often for years on end, in the hope of being on the spot when any non-purchase vacancies arose. From the same source it appears that a further 5.4 percent were ex-NCOs, (up from 3 percent before 1793) exclusive of the ensigns appointed to Veteran Battalions who were almost invariably drawn from the ranks. Taken together the two categories account for just under 10 percent of newly commissioned officers. However, there is good reason to believe that the true figure may actually be higher for this analysis takes no account of an unknown number of men who served in the ranks as private soldiers rather than as volunteers before being commissioned. Perhaps the most notable example of this practice occurred in 1799 when five privates of the then 100th (Gordon) Highlanders were directly commissioned from the ranks. All five had enlisted when the regiment was first raised in 1794 and since one was described as a tailor, and the other four were labourers, it can safely be assumed that none were volunteers.

This rather dandified officer of the 44th evidently belongs to his regiment’s grenadier company. Note the wings and epaulettes on both shoulders embroidered with a grenade badge, and the grenade badge in his cocked hat. (Private Collection)

Whatever his social background, the regulations stated that a prospective ensign had to be aged between 16 and 21, although the upper limit was routinely waived in the case of commissioned rankers and officers volunteering from the Militia. When it came to under-aged officers, the position was by no means as straightforward as it might first appear. There are certainly numerous instances of children being given commissions. James Wolfe, the celebrated conqueror of Quebec, joined the 12th Foot at the age of 15, which seems to have been pretty average for much of the 18th century. There are numerous examples of very young children being entered on regimental books, but the prominence attached to such cases suggests that it was well recognised as an abuse rather than the norm. On the other hand that abuse was afforded a dubious official endorsement by the occasional granting of non-purchase commissions to the deserving orphans of dead officers. Nevertheless, they accounted for only a very small proportion of those carried on the Army List. In a random sample of ten regimental inspection reports of 1791, the youngest officers turned up were aged 16 and the average age was 21.

It is, in any case, important to approach the question from an 18th- rather than a 21st-century perspective. Although children were legally considered as infants until the ripe old age of 21, they normally began their working lives – or at least entered upon apprenticeships – between the ages of 12 and 15, so there was no reason why those contemplating a military career should not do likewise. The situation was exactly paralleled in the Royal Navy, where there was a long-standing practise of entering very young children on ships’ books in order to (quite fraudulently) increase their sea-time and thus assist their eventual careers by boosting their notional seniority.